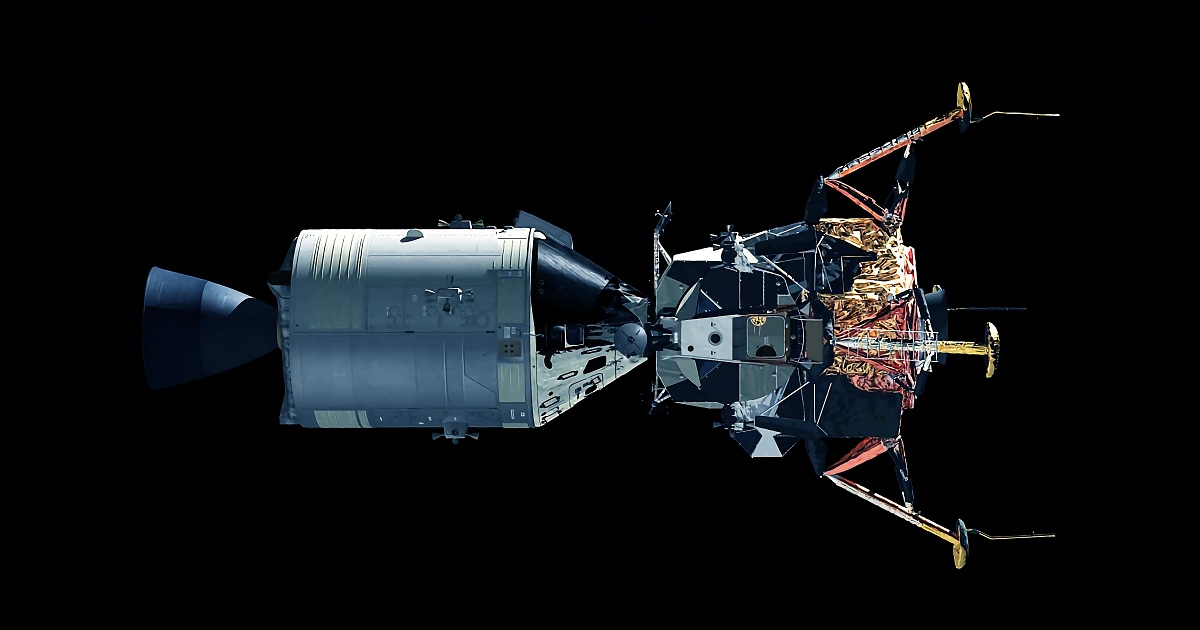

I was rewatching Apollo 13 over the weekend - a fabulous movie, by the way, if you’ve never seen it - about how, in 1970, three astronauts returned safely to Earth following an explosion on their spacecraft, two days into a journey to the Moon.

Among the many problems faced by the crew and mission control was one of navigation. In order to conserve electrical power, they had to shut down their computers, along with their navigation systems, until they powered them up again just before reentry. Of course, this made it far more difficult to plot their course – but it was also far more important that they do so – so that they would be in the right position when they approached the Earth.

Economists, policy makers and investors are today similarly, although less dramatically, in the dark about the trajectory of the U.S. economy. With the exception of one delayed CPI report, we have received no economic data from the federal government for over a month. This undoubtedly makes it harder to assess where the U.S. economy is and where it is headed. However, it also makes it doubly important that we try to do so, so that we are well-positioned for when the data drought ends.

Some Baseline Assumptions

Constructing a forecast in this environment obviously requires greater use of private sector data than would normally be the case. However, like all forecasts, it starts with some baseline assumptions. In particular, we assume that tariffs stay at current levels, after last week’s agreement with China, and the administration maintains its current policies with regard to immigration. We assume that the government reopens within the next week or two and that there are no major fiscal policy changes over the next two years beyond those already scheduled as part of OBBBA. Turning overseas, we assume that the global economy continues to grow at a moderate pace, major foreign central banks, on average, make little change to policy rates and that the OPEC+ group continues to supply oil at a pace consistent with current prices. Finally, we make no provision for political, geopolitical, financial or environmental shocks.

All of these assumptions are, of course, worth challenging and changes in them should be considered the major risks to the forecast. But starting with these assumptions and paying special attention to estimating the most recent missing data, what does this imply for key economic variables?

Growth: Real GDP fell by 0.6% annualized in the first quarter and then rose by 3.8% in the second. We estimate it grew by 2.8% in the third quarter, but may increase by just 0.3% in the fourth, as weakness in consumer and government spending are only partially offset by strong investment spending. Industry data continue to show weakness in tourism while light vehicle sales fell in October with the expiration of electric vehicle credits. Spending by upper income households still appears to be strong. However, higher student loan repayments and tariff inflation should hamper the spending of average households. Meanwhile, the government shutdown, which has now extended for over a month, is reducing spending by the federal government and its employees.

Assuming that the government shutdown ends within the next week or two, we expect real GDP growth to surge to a roughly 3.5% pace in the first half of next year, as consumer spending bounces due to lower income tax withholding and a one-time surge in income tax refunds. Thereafter, spending growth should fall back, absent any further fiscal stimulus, reflecting weak demographics and slow job growth. Overall, even with the AI boom and investment spending tax breaks boosting capital spending, we expect real GDP growth to fall to a pace of between 1.0% and 1.5% between the third quarter of 2026 and the end of 2027.

Jobs: The shutdown has stopped data collection for both the household and establishment employment surveys. At a minimum, this means that the October jobs report, if it is ever released, will be constructed using interpolated data and will, therefore, provide less reliable information on both job growth and the unemployment rate. If the shutdown ends in the next few days, the November surveys may be conducted in their usual manner, limiting the gap in the data.

For economists trying to gauge labor market strength, job openings data from Indeed, payroll data from ADP, perceptions of local job market conditions from the Conference Board, purchasing manager surveys from ISM and weekly state unemployment claims can all help fill in the gaps. So far, collectively, they suggest sluggish labor market conditions although no sharp drop in private employment. The fourth quarter, however, will see a significant decline in federal government jobs, contributing to very low overall job creation and a possible further edging up in the unemployment rate which was pegged at 4.3% in August. Job growth should reaccelerate early next year, due to an expected surge in consumer spending.

Turning to the long-term outlook, in the 20 years between the dot-com bubble and the pandemic, real GDP grew at an annual average rate of 2.11% while non-farm payroll jobs rose by 0.75%. Between 2Q2025 and 4Q2027, we currently expect the economy to grow at a slightly slower 1.81% pace. If payroll job growth is proportional to GDP growth, this would suggest a gain in employment of 0.65% per year, or roughly 85,000 jobs per month.

Actual average job growth may come close to this despite labor supply constraints. Net immigration has fallen sharply from the roughly 1,000,000 annual average in the first two decades of this century. A lack of government data on legal immigration and deportations, which predated the shutdown, makes it difficult to estimate net immigration with precision.. That being said, if, net immigration has fallen to 20,000 per month, or 240,000 per year, then the demographic structure of the U.S. population suggests that we are currently experiencing a roughly 25,000 monthly decline in the working-age population.

However, a lack of available workers will make employers more desperate to hire while a squeeze on living standards for average households may encourage some uptick in recently depressed labor force participation. Consequently, we expect to see slow, but not negative growth in the labor force, with the unemployment rate remain in a range of 4.0% to 4.5% through the end of 2027.

Inflation: The lack of government data on inflation is, if anything, a more serious problem than is the case for employment. Normal field surveys of retailers used to construct the CPI report were not conducted in October so that, even if the October CPI report is eventually released, it will be highly suspect from a data quality perspective. In addition, while monthly employment data refer to the week or pay period that contains the 12th of the month, CPI data are collected throughout the month. Consequently, even if the government shutdown were to end this week, the November CPI report, due out in mid-December, would already be compromised.

Once data collection has finally resumed, we expect it to show a rising impact of tariffs, both in the fourth quarter and in the first half of 2026, as U.S. importers and retailers gradually pass on the cost to consumers. However, flat energy prices over the next few months, combined with a steady decline in shelter inflation and relatively stable wage inflation, should limit the increase in consumer inflation. We expect year-over-year CPI inflation to climb from 3.0% in September to 3.3% this December and then edge up further to 3.5% by June of 2026.

Assuming no further fiscal stimulus, energy shock or supply chain disruption, inflation should then cool, along with the economy overall, in the second half of 2026, with year-over-year CPI inflation falling to 1.9% by the end of 2026 before moving sideways in 2027. Throughout the forecast, we expect consumption deflator inflation to run between 0.2% and 0.3% cooler than CPI inflation on a year-over-year basis.

The Fed and Rates

The somewhat hawkish tone of last week’s Federal Reserve meeting has cast doubt on the future pace of Fed easing, with the odds of a December rate cut falling from 96% just before the meeting to roughly 70% today. Interestingly, Jay Powell indicated that a continued government shutdown might make further Fed easing less likely as it would further obscure the path forward.

Nevertheless, if the economy performs in line with this baseline forecast, the Fed will probably ease in December and could still cut twice more in 2026, bring the federal funds rate down to a range of 3.00%-3.25% and thus touching the FOMC median projection of 3.00% for the “neutral rate”.

Such an environment could encourage further dollar weakness with the Fed easing more than the other major central banks. It would also be broadly supportive of both bonds and stocks. That being said, already low long-term rates and tight credit spreads should limit bond market returns relative to those in equity markets and some areas of alternatives.

Risks to the Forecast

Finally, though, it is important to acknowledge risks to the forecast.

First, we believe the government shutdown will end in the next week or two. Both parties are trying to balance political gain against public pain – revealing, in their lack of effort, the pretty shocking exchange rate they apply between the two. After tomorrow’s mid-term elections and the start of open enrollment for now much more expensive ACA health insurance, the political value of continuing the shutdown should fall, pushing both parties to a compromise. However, such is the level of animosity and dysfunction in Washington that the shutdown could be extended for many weeks more, inflicting further damage on the economy.

Alternatively, it is possible that the Supreme Court rules against the administration on the issue of tariffs imposed under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977. If this occurs, even if the administration tried to replace these tariffs with others, there is a good chance that overall tariff rates would end up lower than those prevailing today – reducing inflation and boosting economic growth.

Congress could also try to inject further stimulus into the economy ahead of the mid-term elections – a move that could boost both economic growth and inflation – but would also, likely, put an end to Fed easing.

The economy could be hit by a financial shock emanating from growing credit concerns in some areas or very high equity valuations.

Or some other shock could occur. Indeed, many of the most important events to impact the U.S. economy in this century, such as 9/11 and the pandemic, were very hard for investors to predict beforehand.

And that is why portfolios should be constructed in a broad, diversified way with due attention being paid to valuations. Without government data, divining the future path of the economy is particularly difficult right now. But it is never easy.

As their damaged spacecraft hurtled back towards Earth, the crew of Apollo 13 obsessively went over procedures – the actions they needed to take right then, and also when the computers came back on line, to give them the best chance of getting safely to their destination. Investors and those who advise them should do the same and with greater urgency precisely because of the current diminished visibility on the direction of the U.S. economy.