At a Glance

- The widespread rollout of vaccinations has unleashed powerful pent-up demand in the U.S. economy, sending prices higher across a variety of sectors. Although inflation is now tracking well above the Fed’s 2% target, we agree with the Fed that much of this surge is likely transitory.

- However, there are aspects of the current inflationary surge that may persist and keep inflation elevated in the medium-term, particularly higher wage pressures, rising inflation expectations and the potential for faster increases in owners’ equivalent rent.

- As we look to 2022 and beyond, we believe a shift from secular headwinds to secular tailwinds could result in modestly higher inflation in the long term. Consequently, we may be entering a “new-old” normal where inflation runs persistently between 2-3%.

- Higher trend inflation and a normalization of monetary policy should result in higher interest rates, which may leave us with a different set of winners and losers than in the prior expansion. As valuations become more important, the rotation from mega-cap stocks to the rest of the market should continue, along with the rotation from growth to value and from domestic to international stocks.

Introduction

As we emerge from the pandemic with some measures of inflation rising at their fastest pace since the 1980s, the biggest question for investors is whether some of this inflation will prove “sticky”. Higher inflation, on its own, could boost long-term interest rates and this effect would be amplified if it also pushed the Federal Reserve to implement a tighter monetary policy. As the direction of interest rates underpins nearly every investment decision, a potential lift-off in long-term rates after years of sitting at near-zero levels would have significant investment implications.

Inflation tends to fall in recessions, most notably in the Great Financial Crisis and the most recent pandemic-induced recession. However, while inflation pressures receded further in aftermath of the GFC, the aftermath of this recession is more likely to be characterized by sustainably higher inflation. While we agree with the Fed that a good portion of the current spike in inflation will be transitory, there are elements of this surge that we believe will be stickier and will contribute to a further increase in inflation expectations and interest rates.

Then as we look to 2022 and beyond, inflation will be primarily determined by its long-term drivers. We believe the headwinds to inflation have eased and the tailwinds have strengthened, potentially pushing inflation to a new range of 2-3% over the long term.

Rising inflation in a powerful post-pandemic rebound

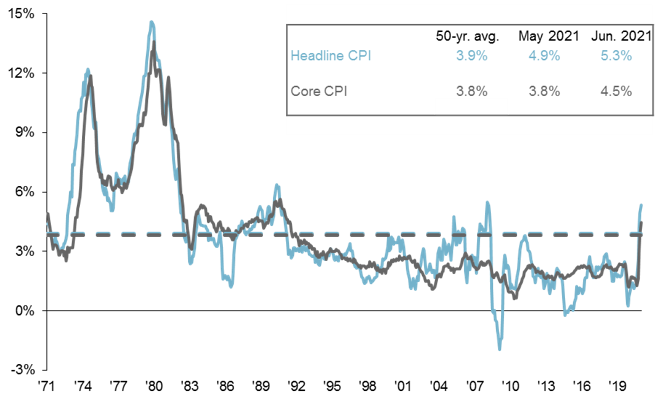

Americans are finally emerging from their socially distant pandemic lifestyles with improved balance sheets and pent-up demand, sending prices higher across a variety of sectors. Most notably, prices are recovering in the worst-hit service sectors from the pandemic, such as travel and hospitality. With higher oil prices and soaring costs for inputs such as copper and lumber, inflationary pressures have been rising across nearly all sectors of the economy. As of June, overall CPI is +5.4% y/y and core CPI, excluding food and energy, is +4.5% y/y. The rise in core CPI is particularly striking, as the core inflation measure had not registered above 3.0% y/y in over 25 years. The year-over-year gain in inflation has been amplified by base effects from last year when prices plummeted during the onset of the pandemic. Even so, CPI on an annualized year-over-2 year basis has been steadily rising year-to-date and is at 3.0% for June.

CPI and core CPI

% change vs. prior year, seasonally adjusted

Source: BLS, FactSet, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. CPI used is CPI-U and values shown are % change vs. one year ago. Core CPI is defined as CPI excluding food and energy prices. Data are as of July 13, 2021.

The Fed has been consistent in their view that near-term spikes in inflation will be transitory, reflecting supply-demand imbalances from the pandemic that should subside as supply chains recover. A vivid example of this is the 45% rise in used car prices over the last twelve months that has been linked to a shortage of new cars which, in turn, reflects a global shortage of computer chips needed for car production. However, the rise in prices has certainly been stronger and more sustained than the Fed predicted earlier this year.

We may be at the peak in year-over-year CPI prints as base effects lessen, but we do think many of the cyclical drivers of recent inflation have more room to run. A continued shift in the consumption of goods to services should further bolster inflation in those sectors. Despite the demand surge, airline fares and hotel rates remain 9.5% and 2% below their pre-pandemic levels, respectively. Meanwhile, data from the Producer Price Index show that input costs have been surging beyond just a few industries, with price pressures most acute further up the supply chain. Commodity prices, a traditional harbinger of inflation, have also been soaring. Given the global nature of commodities, as vaccinations accelerate in Europe and East Asia, commodity inflation could remain strong through the end of the year. Further, as the demand for goods remains exceptionally strong, it is more likely that producers will pass these higher input prices down the supply chain, ultimately resulting in higher consumer inflation.

Another factor contributing to higher inflation is rising home prices. Home prices are surging on the back of a pandemic-inspired wave of demand for suburban housing amidst very low mortgage rates. The April Case-Shiller report on home prices showed a striking 14.9% y/y gain in average home prices. While housing is a big part of the overall inflation equation, making up almost a third of the CPI, supply-demand price dynamics are not directly reflected in the owner’s equivalent rent (OER) component to inflation. OER heavily smooths the changes in rental inflation and its weights are based on homeowners’ estimates of a hypothetical rent for their property, which likely lag the supply-demand dynamics of the housing market. OER has only modestly risen as home prices have surged, but inflation is real for those looking to buy a home and is likely contributing to the rise in consumer inflation expectations. According to the University of Michigan survey of consumers, consumer expectations for price changes over the next 5-10 years has increased to 2.9% as of July from 2.3% in March 2020.

While we tend to agree with the Fed that a good portion of this surge in inflation will be temporary, there are clearly elements of “stickiness” that should keep inflation elevated over the medium term. Rising rental prices could provide a more sustained boost to consumer inflation. Further, if the transitory flames of inflation burn hot enough and for long enough, it’s more likely some of it will get embedded into inflation expectations, which have the ability to make inflation a self-fulfilling prophecy. This is starting to play out, with the 10-year breakeven inflation rate rising to 2.6% in May, its highest point in more than a decade, before moderating to about 2.3% as of mid-July. The survey conducted by the Philadelphia Fed also shows long-term inflation expectations by professional forecasters have risen modestly to 2.3%.

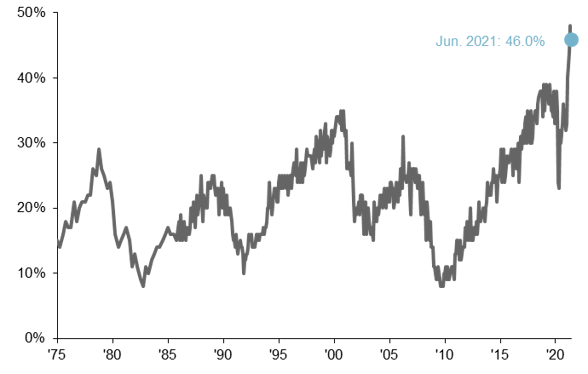

Another key element to determining how much of this inflation will prove sticky is wages. Labor demand has been exceptionally strong as businesses struggle to hire enough workers to meet the surge in consumer demand. JOLTS non-farm job openings reached a record high of 9,209K in May, while figures from the National Federation of Independent Business show 46% of small-business owners reported unfilled job openings in June, the second largest share in the survey’s 46-year history. The hunt for labor has sent wages higher across nearly all major sectors of the economy. Wages have risen 4.6% on an annualized year-over-2 year basis, which sidesteps the base effects from last year. Workers are seemingly taking advantage of labor market tightness as well, with elevated labor market churn reflected in the rise of the JOLTS quits level to a series high of 3,992K in April, before easing to 3,604K in May. The expiration of enhanced unemployment benefits and the easing of pandemic-related distortions on the labor market should allow employment to recover in the months ahead. However, the long-standing shortage of skilled labor, reduced immigration, and increased retirements as a result of the pandemic could constrain labor supply over the longer term and may keep wages elevated.

NFIB Small Business Jobs Report, jobs hard to fill

% of firms with 1 or more jobs unable to fill, seasonally adjusted

Source: National Federation of Independent Business, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Data are as of July 13, 2021.

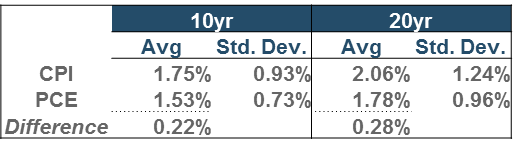

It’s also worth noting that the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation is the Personal Consumption Expenditures Deflator (PCE), which tends to be less volatile and lower than the CPI. This is due in part to a number of differences in the composition of the indices, including somewhat different weights ascribed to different parts of consumer spending and the use of fixed weights in the CPI measure. This has led PCE to average 0.22% below CPI over the last 10 years. With the current volatility in the CPI measure, this gap is now particularly wide at 1.0% in May. That being said, we estimate PCE inflation in the fourth quarter of 2021 to average above 4.0% y/y, well above the Fed’s 3.4% expectation as outlined in its June Summary of Economic Projections.

CPI vs. PCE

Source: BEA, BLS, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Data are as of July 13, 2021.

A wide-angled lens on inflation

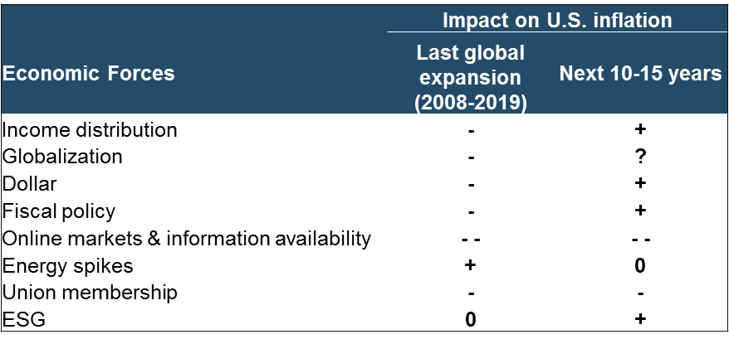

While much of the great inflation debate surrounds the strength of the current cyclical drivers of inflation, inflation over the long run will be determined by the mix of its secular headwinds and tailwinds.

Inflation has been declining since the 1970s due to a number of long-term forces. First, information technology has tended to increase the competitiveness of all markets by empowering buyers both at the consumer level and the wholesale level. Second, income inequality has been on the rise in the United States. This has tended to reduce the demand for goods and services and increase the demand for financial assets, simultaneously boosting asset prices while restraining consumer inflation. Third, increased globalization has tended to reduce inflation by allowing consumers in generally rich countries to take advantage of lower labor costs in poorer nations. To some extent, this is illustrated by the rise in the value of global exports and imports which, according to the World Bank, rose from 27% of global GDP in 1970 to 61% by 2008.

Other forces have also served to reduce inflation. Oil prices, a trigger of higher inflation in the 1970s and periodically since then, have recently traded in a narrower range, partly because of the advent of shale oil which can respond quickly to changes in demand. Declining union power has also tended to reduce wage inflation. More recently, a combination of fiscal austerity and monetary stimulus in many nations after the GFC proved very ineffective in stimulating either real economic growth or inflation. Finally, information technology, and productivity-enhancing investments in artificial intelligence and robotics have reduced inflation pressures in recent decades.

However, in the wake of the pandemic recession, many of the headwinds suppressing inflation have diminished while new tailwinds have materialized.

Political populism and the need to combat the pandemic’s economic impacts have encouraged governments to adopt far more aggressive fiscal stimulus. This is likely to prove more potent than the monetary stimulus of the last decade, in part because much of it is directed towards lower and middle-income consumers who have a greater marginal propensity to spend. Globalization has also stalled, due to greater protectionism and an increasing share of services, which are less tradable, in global GDP. Between 2008 and 2019, the value of exports and imports fell from 61% to 60% of global GDP.

Politics may also contribute to higher wage growth, reflecting higher minimum wages and more generous unemployment benefits. A focus on battling climate change could have the same effect, if it includes higher carbon taxes rather than just subsidies for green technology. Finally, a falling dollar may boost inflation by raising the prices of imported goods paid by U.S. consumers, while the reverse has held inflation down in recent years.

On balance, we believe the shifting mix of headwinds and tailwinds suggests modestly higher inflation in the long term. Consequently, as we emerge from this pandemic, we may be entering a new-old normal for inflation. After the great inflation of the 1970s, inflation came down significantly but remained in a 2-4% range for much of the 1980s. The aftermath of the GFC, on the other hand, defined a new normal of stagnant inflation running persistently below the Fed’s 2% target. The aftermath of the pandemic recession may be characterized by inflation once again running between 2-3%. This range of CPI inflation would roughly equate to a 2.0-2.5% PCE inflation rate.

Economic forces

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Investing in the new-old normal

Assuming at least some of the recent surge in inflation sticks around, even a modest tilt towards a normalization of monetary policy should lead to significantly higher interest rates, particularly in a world where fiscal policy is still very aggressive. This may leave us with a different set of winners and losers than have dominated in recent years.

As rates rise, valuations should become more important. Many investments can be financed profitably with interest rates at close to zero and, while asset prices are generally high, a long period of cheap financing has favored the speculative over the prudent. With higher interest rates, investors should continue to rotate from mega-cap stocks to the rest of the market and from growth to value, which tends to outperform during periods of above-trend economic growth and rising rates. As the global recovery gains steam, investors may also want to increase exposure to more cyclically-oriented markets that stand to benefit the most, such as Europe and Japan. Fixed income investors would be well advised to stay short duration, as higher interest rates pose a greater challenge to long-duration bonds. Lastly, higher inflation also supports alternative assets, particularly core real estate, transportation, and infrastructure, which can serve as an inflation hedge and a diversified source of income for investors.

As investors prepare for a post-pandemic environment, modestly higher inflation and therefore interest rates pose both risks and opportunities across the investment landscape, underscoring the need for careful asset allocation and active management.

09mf211407214105