Negative rates – how low can you go?

10/10/2019

Jason Davis

At first sight, it seems the global financial system has gone crazy. In Switzerland and Denmark, large consumer balances now attract negative interest rates between -0.6% and -0.75%, whilst large corporate balances have been subject to charges for some time now. In fact, Danish banks have taken the phenomenon one step further, offering 10yr mortgages at -0.5%. If you would like to lock in for longer, you can get an interest free mortgage for 20yrs or pay 0.5% for 30yrs. We are now in a world where you pay-to-lend and earn-to-borrow.

Why go negative?

In an attempt to reduce real interest rates in a world of low (and falling) inflation expectations, central banks have turned to negative policy rates. There are two main transmission mechanisms of negative rates. Firstly, they push longer term yields lower via altering the path of future rate expectations. On top of this, they also compress term and risk premia as investors shift into longer-dated and riskier assets. Ultimately this feeds into household and corporate lending rates, the key result of negative policy rates. The second transmission is (theoretically) via the currency as investors are forced out of negative yielding assets and into positive yielding assets abroad.

What about the side effects?

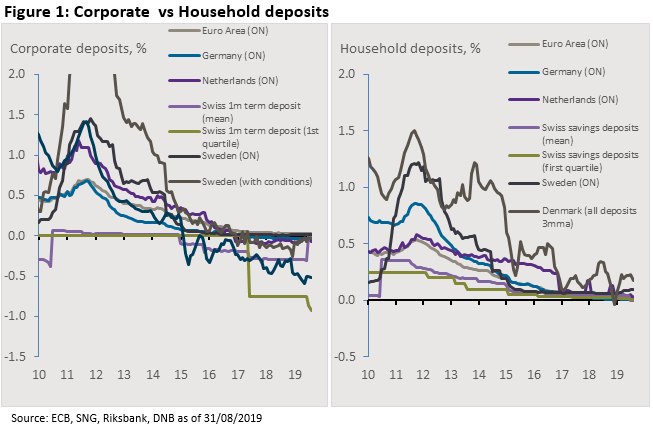

There is an ongoing debate that negative interest rates actually hurt the economy due to its impact on banking profitability. One of the main roles of banks as a financial intermediary is to accept deposits and lend to the private sector. As interest rates fall, the spread between these assets (loans) and liabilities (deposits) declines, pushing net interest margins lower. This is especially damaging when interest rates turn negative. Whilst banks have managed to pass on negative interest rates to some corporate depositors, it is very difficult to pass them onto the consumer (Figure 1). Hence the interest rate on bank liabilities is somewhat floored whilst the yield on their assets continues to plummet. The implication being that, in theory, we should reach a point where it becomes too damaging to continue accepting deposits and lending. At this point, lending volumes would start to contract and rate cuts would no longer be passed on.

So what does the evidence say?

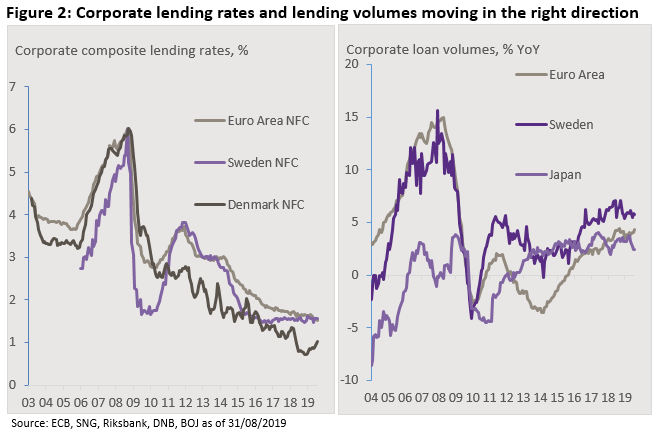

The evidence suggests that negative rates are not contractionary, yet. The key transmission mechanism of negative rates is the pass-through to lending rates. The data continues to show declining corporate and household lending rates and increasing growth in lending volumes in negative rate countries (Figure 2)

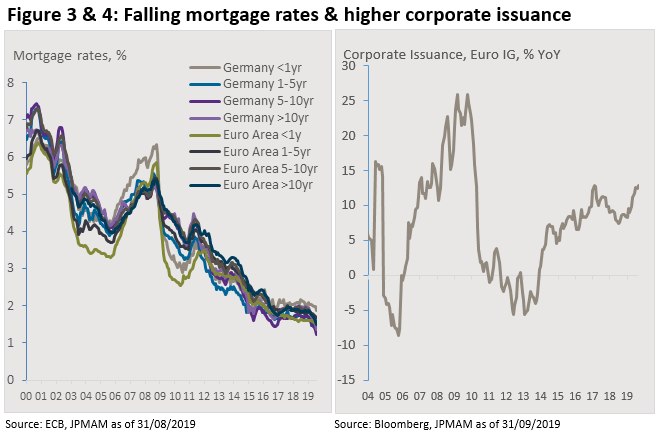

Lower rates do benefit households and companies. The main household liability, mortgage rates, have been declining significantly in the negative rate era (Figure 3), whilst consumer deposits have been mostly shielded from negative rates so far. On the corporate side, whilst large deposits attract charges, this is more than offset by declining interest rates on the majority of their liabilities (issued debt and loans). In fact, a combination of negative interest rates and CSPP has boosted corporate issuance significantly.

What about all those savers?

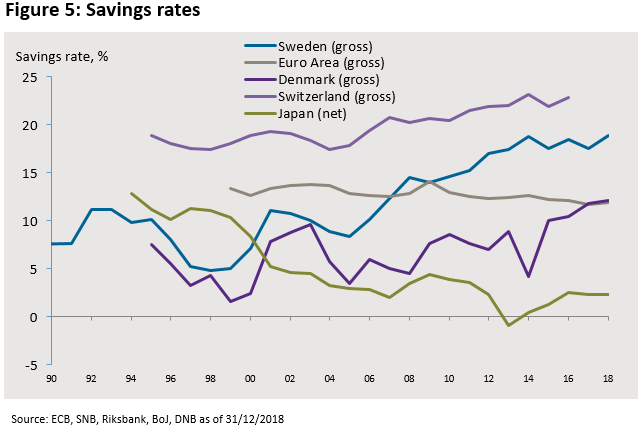

Monetary policy always has winners and losers – clearly savers are one of the losers here. In general, it is assumed the negative income effect on savers from easier monetary policy is more than offset by the positive impacts elsewhere. The concern, however, is that as interest rates fall and deposit rates move negative, the consumer may react by saving more, not less. This is called the paradox of thrift and is not new. Any reduction of interest rates will lead to some element of compensatory saving, even when interest rates are positive. The question going forward is whether passing negative rates onto consumers will see a psychological shift which will snowball this paradox of thrift. So far the data does not suggest an obvious acceleration in savings as a result of negative rates elsewhere (Figure 5), however, we have not yet seen the impact of negative rates on consumer deposits.

So far I have argued that the pass-through of monetary policy remains intact even at these levels of interest rates, at least for now! The ECB place a lot of emphasis on falling lending rates and rising lending volumes and so far these continue to travel in the right direction. Furthermore, peripheral and credit spreads have continued to tighten due to the insatiable desire to avoid negative interest rates on savings (portfolio channel). That said, whilst I believe the transmission mechanism remains intact, there are two key issues to focus on going forward.

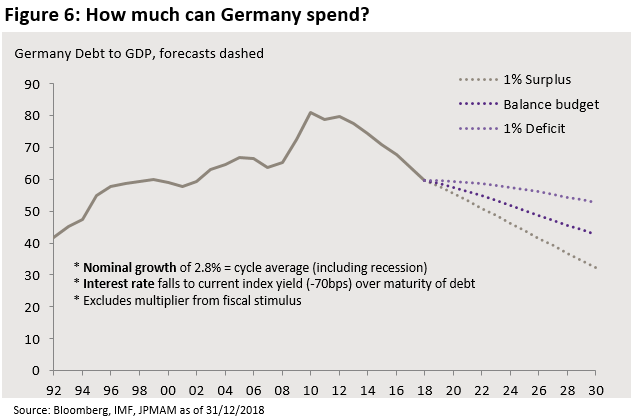

The first is how much do these incremental moves in lending rates really impact the economy in terms of growth? Whilst lower rates should encourage leverage, they cannot force households and companies to spend and invest. The key missing ingredient from a growth perspective is fiscal policy. Germany can borrow for 30yrs at negative rates – in fact their debt trajectory would still be downward sloping even if they spent an extra 2% of GDP per year. The ability to spend is there, the willingness is growing slowly.

How low can we go?

The second issue is at what point does the transmission mechanism break?

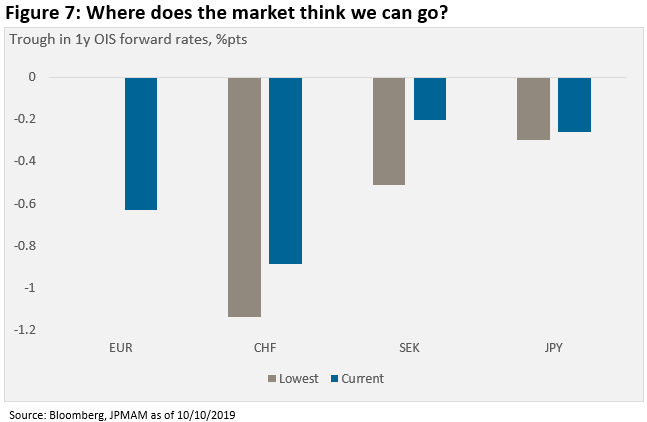

So far the market has priced, at its low, a trough of -80bps in the Euro Area, and -1.1% in Switzerland. Whilst these terminal rates have moved up a bit since the last ECB meeting, it is very possible we will reach these levels and maybe go even further if the economic data continues to deteriorate. I would not be surprised by a -1% policy rate in the Eurozone in the next recession.

In my mind, there are two steps on the path to ever lower rates. The first is the point at which banks begin to pass negative rates onto the consumer – which we are already starting to see. Psychologically, it is easier to pass negative rates onto consumers in the form of account fees and charges. Despite the first mover disadvantage and some legal hurdles, eventually banks will need this release valve.

The second step to the lower bound is therefore at what point the private sector hoard cash rather than store it as bank deposits. At this stage of the blog, I must admit we are walking in the dark. Nobody has ever gone lower than -0.75% so you need to get innovative to estimate that lower bound.

There are two elements to the cost of hoarding cash. The first (and more predictable) is the cost of storage and insurance. The Bank of Canada estimate of ~0.5% (based on ETF fees for precious metals) seems like a reasonable starting point for this cost. The more difficult cost to estimate is invisible – the convenience cost of holding cash as well as the reputational cost associated with trying to “undermine” the system. A number of attempts have been made to estimate these costs resulting in a wide range of results. The one thing they have in common is that the cost can be quite large, pushing the 0.5% initial starting point much higher.

Central banks will move slowly, continuing to test the lower bound as economic conditions worsen. They will be watching the transmission to lending rates closely, all the while hoping that fiscal policy takes the lead in transmitting lower rates into stronger growth.