The shadow productivity escape hatch

22/02/2018

Andrew Norelli

Low potential growth in the US hasn’t been a problem for quite some time, even though I’ve focused on it as a looming concern for a couple of years now. So far it hasn’t mattered, and the disconnect lies in the lack of inflation pressure in recent years, despite falling unemployment, and no obvious increase in labor productivity. The way the theory goes, if all three of those are true, then by definition there is still “slack” in the labor market, and the unemployment rate that sparks inflation (NAIRU) is simply lower. Now though, genuine inflationary concerns are back in the narrative. Core CPI and PPI are actually printing higher, and the unemployment rate is 4.1%, down from 4.8% a year ago. Layer on top of this the double whammy fiscal stimulus from the tax cuts and the deficit-increasing budget agreement, and all of a sudden the low potential growth rate looks like a problem once again. It is fixable, as I’ve detailed in these pages before with concrete proposals, but even without structural reforms, there is still an escape path which I’ll outline today.

A quick review: in a sense, durable economic growth can only come from two sources: growth in hours worked, or growth in output per hour (labor productivity growth). When an economy is at full employment, growth in hours worked itself has only one main source: working-age population growth.[1] So, in effect, the potential growth rate of an economy at full employment is growth in the working age population + labor productivity growth. When an economy still has slack in its labor market – a ready supply of unemployed or underemployed residents eager to work – then growing faster than potential is the way to reduce unemployment. However, when an economy reaches full employment, productivity growth must then also occur to lift potential, otherwise inflation pressure builds. Therein lies the risk in pro-cyclical fiscal stimulus, especially stimulus that does not focus strategically on growing productivity.

So where are we now? Most demographic estimates put the working age population growth over the next 5-10 years at 0.3-0.5% per year. My own estimates using census data suggest 0.4%, and the Pew Research Center estimates 0.3% for each of the next two decades.[2] Both of these estimates assume immigration trends which prevailed prior to 2017, so if anything, the risk to these numbers is to the downside.

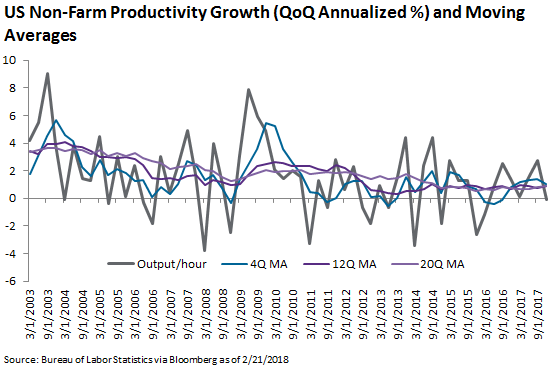

Secondly, notwithstanding a false dawn or two, productivity growth has so far shown no signs of picking up. While the data is noisy, 1y, 3y, and 5y moving averages all seem to suggest that productivity is still stubbornly stuck around 1% growth post-crisis:

So despite headline GDP growth prints in the 2.6% – 3.2% range for recent quarters, potential growth is currently still slow, probably around 1.4% (0.4% population growth + 1% productivity growth). This gap would jibe with the ongoing 150k-200k job creation per month, and the still-declining unemployment rate.

None of this data yet reflects the effects of the tax cuts and the budget agreement, but we know they’re coming. This fiscal stimulus makes a near term recession almost impossible, because it is quite literally manufactured GDP growth, but the growth injection strains the gap between realized and potential growth right when the economy is probably reaching and likely to exceed full employment. I see several possible outcomes:

- Realized growth accelerates, but neither population nor productivity accelerates, so potential growth remains low. However, some labor market slack still exists, such that NAIRU is just lower – say 3% for the sake of argument. Realized growth can exceed potential dramatically without inflation pressure building. Over the short term, this is very positive for the economy and risk markets, because it allows more of the same for another ~2 years: the Fed can gradually normalize policy without inflation pressure as an immediate threat (i.e. they can allow growth to remain strong). Eventually, the recession is worse when the Fed is inevitably forced to restrain growth down toward potential to stop inflation, and the gap is big so the brakes have to be pressed hard. This outcome is unlikely because inflation is already accelerating to a degree.

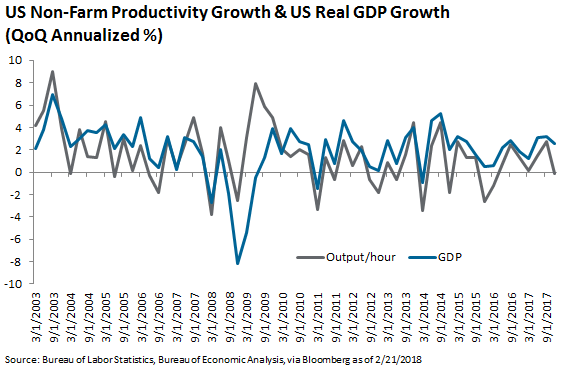

- Realized growth accelerates and the economy is at full employment, but productivity growth accelerates concurrently, lifting potential growth and preventing inflation pressure from materializing significantly. This situation allows high levels of deficit-fueled realized growth to persist, without the need for the Fed to aggressively intervene. This is the most market-friendly outcome, but how likely is it? Well, count me among those who believe there is little in the tax bill that is designed to directly influence productivity to the upside. Accelerated depreciation of capital expenditure should, in theory, subsidize businesses’ modernization of productive equipment, which ought to help, but in prior years significant bonus depreciation was already available. Full expensing is better, but in my view it’s unlikely this element of the plan will lead to a material improvement in labor productivity. However, I also believe that productivity doesn’t necessarily need an economic or policy reason to rebound. The ebbs and flows of productivity growth actually tend to correspond to similar ebbs and flows in the quarterly GDP data:

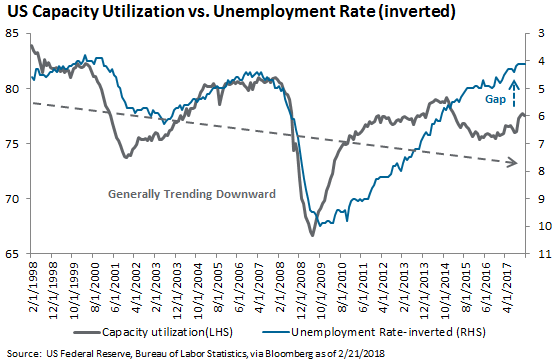

This pattern suggests that as growth expands, on some level labor productivity can expand to meet the increased demand, i.e. the average worker has excess capacity in reserve. Capacity utilization statistics have been very generally trending lower, and current utilization is lower than would be typical at this point in the cycle with unemployment as low as it is:

Another potential source of on-demand productivity growth, though purely anecdotal and speculative, would be some “good” forms of automation (labor enhancing, not labor replacing). In a tight labor market, augmenting existing human capital with automation (in the absence of sidelined workers to hire), raises output per worker. Whether increased output accrues entirely to capital over labor is a matter of debate, but regardless, if real output per worker-hour increases, labor productivity stats will increase by construction[3], and workers will have a shot at real (non-inflationary) wage increases. These spikes in productivity in response to demand spikes I refer to as “shadow productivity” coming online, and it’s one plausible escape path from persistently low potential growth rates.

- The most likely outcome is that the pro-cyclical deficit spending results in a sugar-high of increased realized growth with no productivity increase, such that the Fed or the market via tighter financial conditions needs to slow down growth toward potential, to restrain inflation pressure. This is what leads us to the “Phase 1” discussed in last month’s commentary. If Phase 1 is a relatively shallow tightening of financial conditions (similar to the price action during February), realized growth will still show an unacceptable gap to potential, and the Fed will be forced to tighten despite the sell-off in markets. One way or another, financial conditions need to tighten if potential growth does not expand via demographics or productivity. Once this is achieved, then Phases 2 and 3 can proceed.

So we’re in a bit of a lull at the moment, where the market is trying to figure out whether bona fide inflation risk is on the horizon, and if so, what’s going to give? Either the recent perking up of the inflation data is a red herring, and we still have labor market slack left (outcome 1), we’ve got a productivity rebound forthcoming in which a higher growth plateau is sustainable without an inflation spike (outcome 2), or potential growth rates stay put and tighter financial conditions are going to be necessary at some point this year to head-off inflation pressure (outcome 3). I’m sticking with the third option as most likely.

[1] Increases in the length of the workweek is another source, but other than dipping slightly by half an hour in the depths of the crisis, the US work week has remained very stable at 34.3-34.7 hours per week for more than a decade.

[3] This effect is totally separate from the common “measurement error” concerns about productivity and technology.