What is R-star and is it rising?

12/10/2017

Jason Davis

Since policy tends to work with long and variable lags, central banks must attempt to forecast the future. To help them do so, there is a toolkit of “abstract unobservables” such as NAIRU, potential output and the Phillips curve. Policymakers spend a lot of time estimating these variables to determine and explain policy.

One unobservable that has been the focus of much policy debate recently is R-star (r*), more formally known as the real neutral rate of interest.

So what is R-star?

R-star is the real neutral rate of interest that equilibrates the economy in the long run. Less formally, it is the real interest rate that is neither expansionary nor contractionary when the economy is at full employment. The theory goes that if the central bank sets the base rate below R-star then policy is accommodative – the further below R-star the more accommodative. Hence understanding and estimating R-star is essential for the formulation of monetary policy.

Whilst the actual level of R-star is a matter of debate, there is a general agreement that it has fallen significantly since the financial crisis. There have been many reasons cited for this. These include, to name just a few, more volatile and negatively skewed economic growth, aging populations, lower cost of investment, higher leverage and lower productivity.

A low and falling R-star can partly explain why inflation has remained low, despite falling nominal interest rates. This phenomenon created a big problem for central bankers during the crisis. This is because there are only two ways to reduce the real interest rate: reduce the nominal base rate or boost inflation expectations. When central bankers hit the zero lower bound they had to become innovative – hence the expansion of monetary policy beyond just setting interest rates.

So what are central bankers saying now?

After years of low or negative interest rates, quantitative easing and forward guidance, all an attempt to keep the real policy rate below R-star, many central bankers are now arguing that R-star may be on the rise.

Janet Yellen, Mario Draghi and Mark Carney have all said, in some form or another, that interest rates may need to rise just for policy to stand still. In other words, as R-star rises the central bank must increase rates to maintain the same level of accommodation.

So is it actually rising?

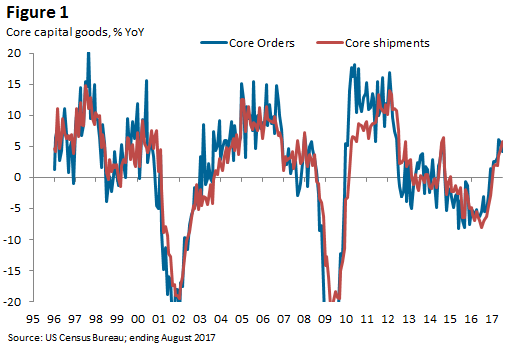

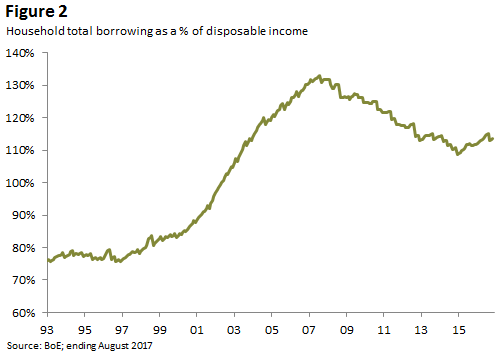

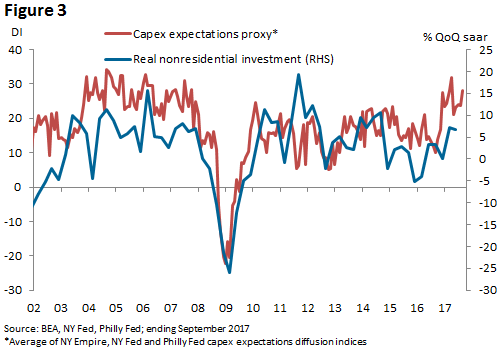

R-star fundamentally depends on the population’s desire to save and invest. Central bankers have recently pointed to some evidence that this trade-off has started to shift. For example, capital goods new orders and shipments, a leading indicator of US investment, have been on the rise (Figure 1). In the UK, the Bank of England has pointed to the end of consumer de-leveraging as evidence that the economy is starting to demand higher real interest rates (Figure 2). Finally, US capex expectations are close to all time highs (Figure 3)

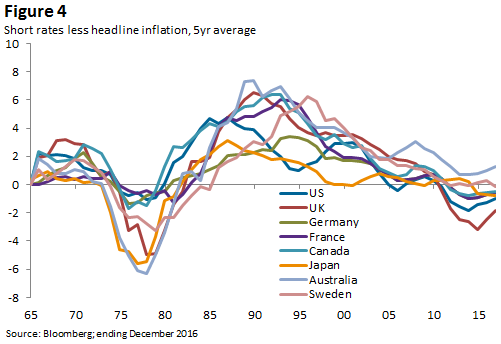

The problem with these arguments is that R-star is a structural slow moving variable. It is dangerous to use cyclical evidence such as stronger growth or higher investment as a reason for a structural change. Whilst real interest rates tend to mean revert, they do so over decades, not years (Figure 4).

Furthermore, although a lot of the factors that would reduce trend growth have also reduced R-star, in reality, there is very little theoretical or empirical evidence of a direct link between the two.

In fact, above trend growth, growing capital expenditure and consumer leverage are not necessarily evidence of a rising R-star, but more likely evidence of accommodative policy and mid to late cycle behaviour.

The factors, mentioned earlier, that have pushed this abstract unobservable lower do not change overnight and certainly do not change quickly enough to justify a significant hiking cycle.

Implications for markets

Regardless of whether R-star is on the rise or not, central bankers are talking about it, even using it as a reason to shift policy. I remain skeptical that R-star can rise quickly enough in any given cycle to justify significant tightening in policy. This would become apparent if central banks tightened too quickly in a low inflation environment.

That said, regardless of how central banks communicate their decisions, their words cannot be ignored. Whilst inflation remains below target in many developed economies, growth is the strongest and most synchronized since the start of the cycle. A gently rising R-star, if that is the case, is just another reason to move away from such ultra-accommodative policy, even if just gradually. Hence, our expectation is that the Federal Reserve will raise rates once again in December, that the ECB will reduce its bond purchases at the start of next year, and that the Bank of England will raise rates in November.