Talking about ending QT is not the same as doing it

07/03/2019

Andrew Norelli

Given the market’s buoyancy over the past two months since the Powell Pivot, we could all be forgiven for thinking the Fed’s jawboning is just as good as actual policy action. There was a fair amount going on under the radar though which contributed to that potentially false sense of security. Back in January, I outlined a case for market strength through the end of February, based on a temporary reprieve from tight liquidity conditions (QT) which were otherwise stifling markets through the Three Phases cycles in 2018. I was focused at that time on the upcoming dynamics of the Treasury General Account, but there was another fortuitous dynamic at work too in the Fed’s securities roll-off that I missed, which I’ll briefly detail below. The upshot is that right when the Fed began to signal their plans to end QT “later this year,” quirks in the balance sheet dynamics actually resulted in periods of growth of bank reserves. This meant a sneaky and unintended pause in QT right when the Fed discussed a permanent end to it at some unknown future date. The market got a dose of what no-QT feels like, but now in March, the reality of $50 billion per month of liquidity withdrawal is likely to return.

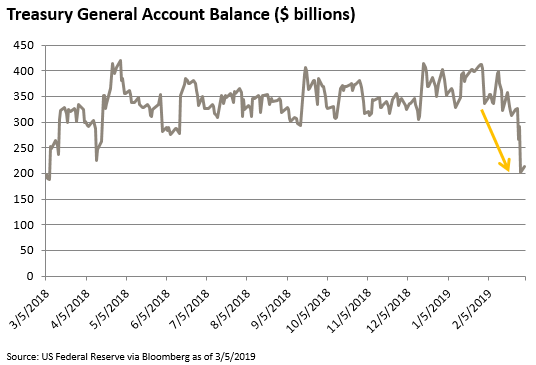

In January, I suggested that because of a requirement in the 2018 legislation which suspended the debt ceiling, the Treasury would be required to spend down its “checking account” held at the Fed (the Treasury General Account or TGA) by a substantial amount by March 1st. They did that (Chart 1), and for reasons I laid out in the last post, this had a similar impact on the money supply as Quantitative Easing.

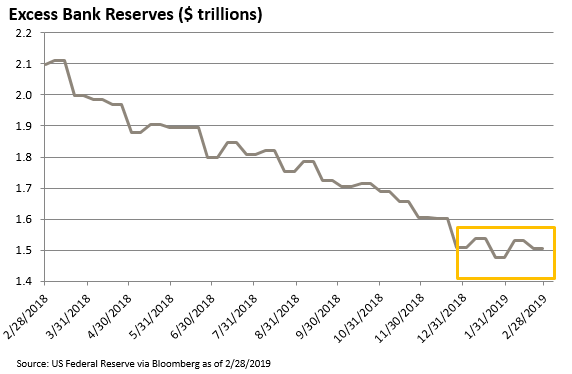

Auspiciously, at about the same time as the Treasury was a net spender of money into the economy, there was a bit of a dead spot in the roll-off of securities held on the Fed’s balance sheet, so that in aggregate, the QT amounts did not reach the desired $50bn per month pace. For the six weeks ending February 13, 2019, only about $31bn worth of securities matured, which is less than half the speed of QT allowed by size of the roll-off caps. After February 13th, the TGA effect intensified.

The combination of these two effects has generally held the quantity of bank reserves in the system so far in 2019 roughly flat, whereas the pace of reserve drain in 2018 proceeded briskly without interruption (Chart 2).

This is about to change. We expect the Treasury to rebuild the TGA as they undertake the first phase of “Extraordinary Measures,” in which they free up some space in the debt ceiling through accounting maneuvers with the Treasury holdings of various Federal employee pension funds. The timing of that is uncertain, but at a minimum the TGA should stop shrinking here for a time. Additionally, the roll-off calendar for securities held on the Fed’s balance sheet is less friendly. In essence, the dead spot is over and QT is now proceeding on-pace for $50bn per month.

Reluctantly, I still feel like this sets the market up for one last period of stress which ultimately forces the Fed out of QT. In other words, I think QT ends on the market’s terms, not the Fed’s. I say that because I still think that negative balance sheet flow – a shrinking monetary base – is a negative thrust on asset prices even if the Fed has already clearly signaled their intention to end it “later this year.”

Simultaneously, there is significant optimism in the market right now for the growth effects of Chinese stimulus – particularly the January spike in Total Social Financing which injected a record 5% of GDP worth of new loans in just one month. That is a green shoot for sure, but prior episodes of Chinese stimulus through an acceleration of indebtedness (a positive credit “impulse”) had a demonstrably lagged effect on global growth, industrial production, EMFX, and the Chinese domestic economy. Historically, those lags were about 6 to 9 months. So, that takes us to July for the effects to show up in the data. Meanwhile, the near term trajectory of data in Europe, China, and US may or may not improve, but any improvement probably won’t be because of Chinese credit creation. The timing of this lagged effect of Chinese stimulus also leaves us with a potential void of helpful data over the near term while the markets await confirmation of the size and effects of Chinese stimulus.

Bottom line, my expectations for the year as a whole have not changed since January, but the markets and the calendar have moved on to the next part of the pathway where near-term caution is once again warranted.