Printing versus burning

20/04/2017

Andrew Norelli

The dynamics of the Fed balance sheet have flared up in the macro discourse once again, and for a host of reasons, that discussion has evolved toward a recognition that monetary policy post-QE is simply different, and that if a shrinkage of the balance sheet is undertaken, the “right” size for the balance sheet is probably significantly larger than it was pre-crisis. Notwithstanding the irrelevance of the debate if political disruption worsens in the coming months, I want to examine two of the less talked-about considerations that suggest to me that the optimal balance sheet is larger than what’s implied by the pre-crisis trend, and reduction should be undertaken only if policy rate tightening is demonstrably insufficient to restrain inflation pressure.

At a primordial level, the Fed’s balance sheet supplies currency in circulation (physical cash) as the medium of exchange. Demand for cash is generally increasing. Perhaps surprisingly, without an expanding supply of the medium of exchange, economic growth is otherwise deflationary. Imagine a group of marooned shipwreck survivors establish an island economy with a fixed money supply; say a finite number of sea shells.[1] Economic growth will ensue as the survivors each work to support the society according to their respective competitive advantages. Hunters hunt, builders build, farmers farm, etc. Productivity expands, as does the real value of the output, but because the number of sea shells is fixed, prices for a given unit of output will trend downward over time as the fixed number of shells is needed for an ever-increasing number of transactions in the economy. That deflationary effect would intensify over time as demographic effects of increasing population contribute to rapid growth in real output, but with that same fixed number of sea shells circulating as the medium of exchange. As prices decline, sea shells would get subdivided. Parallel mediums of exchange would likely surface.

Avoiding this effect is one of the reasons that central bank balance sheets tend to increase over time in modern fiat currency regimes. If economic growth is desirable (it is [2]) and the central bank has a positive inflation target (all are positive), then currency in circulation generally needs to trend upward to facilitate increasing transaction volume. Currency in circulation right now comprises about $1.5 trillion of the $4.5 trillion total Fed balance sheet, and that’s up from only $800 billion pre-crisis. The rate of growth in demand for cash has also increased, despite the slowdown in nominal GDP growth.

Additionally, bank deposits are supplanting physical cash as the medium of exchange. Employees are paid by direct deposit, checking account balances are transferred from buyer to seller electronically, bills are paid electronically, and credit and debit cards facilitate the convenience of electronic payment as much as they facilitate extension of credit. This makes a difference. In the primitive island economy above, bankers will bank: someone will take deposits and make loans. That action at a fundamental level though, results from demand for credit, not demand for the medium of exchange. As long as there is no easy way to pay for stuff on the island with deposits (transactions require sea shells of which there is a finite amount), the lack of sea shells would still constrain the economy through transaction volume.[3] In contrast, in our modern economy bank deposits are now nearly fungible with cash because they’re directly spendable, and as such, are supplanting cash as the medium of exchange. This is a long winded way of saying we need deposit growth over time to avoid deflation, the same way we needed physical cash growth in generations gone by.[4]

In the pre-crisis days, the Fed did not directly create bank deposits. The commercial banking system responded to demand for credit, and sought deposits to fund their credit creation (lending), which in turn created more deposits. The Fed wasn’t involved, other than indirectly influencing demand for credit through their interest rate policy. Credit creation by commercial banks is still a major driver of deposit growth, but now post-crisis, the Fed has a direct role as well. Through their QE programs, the Fed facilitated significant increases in bank deposits. The Fed bought bonds from the private sector, which in turn deposited the money in banks, which in turn deposited the money at the Fed as excess reserves.

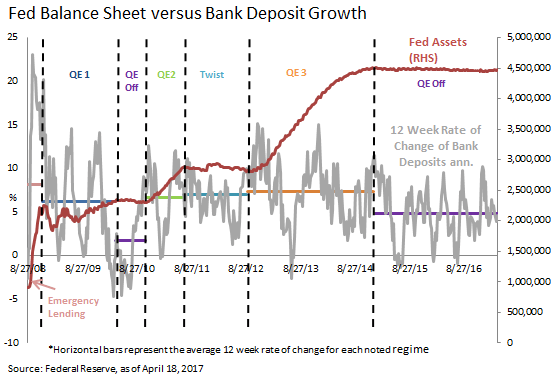

During periods of time in the last eight years where the Fed was actively expanding its balance sheet through QE or the various rescue lending programs, deposit growth in the commercial banking system was noticeably higher than when the taps weren’t open (note the purple bars in the chart below). With the Fed balance sheet flat-lining in 2010 and since 2015, deposit growth slowed to 3.5% and 4.5% respectively. These are the lowest sustained deposit growth rates since the early 1990s. I suggest that shrinking the balance sheet through a reduction in excess reserves will further slow deposit growth or even contract the total level. The anti-inflationary impulse from this would be significant. Without a very robust increase in credit creation to offset the effect, a serious tightening of financial conditions would ensue.

For those that follow the debate about the Fed balance sheet actively, I’m not at all diminishing the importance of concerns about the reversal of the portfolio rebalance channel, widening term premiums, or the unknown impact of various regulatory changes on demand for excess bank reserves. I’m extending those concerns to highlight the increasing potential significance of bank deposits as a driver of inflation and nominal GDP growth, and the relationship between the change in the size of the balance sheet and deposit growth. In the old central banking regime, the Fed acted reactively to deposit growth by supplying scarce reserves. Now, in a market saturated with reserves, they’re a driver of deposit growth (or potentially shrinkage). For all these reasons, balance sheet reduction has the potential to significantly tighten financial conditions, and should be used when the policy intent is a significant tightening of financial conditions. That is, when materially brisk policy rate tightening isn’t getting the job done.

[1] To be precise, this is a finite monetary base. Higher order monetary aggregates are not necessarily fixed.

[2] "Structurally Slowing Growth Implications," May 2016.

[3] The sea shells remain the monetary base and medium of exchange. The deposits, though part of the “money supply,” are not directly spendable on the island and therefore belong to a higher order monetary aggregate: M1 under the American definition.

[4] And yet, physical cash demand remains high. The strongly held suspicion is that most of the physical cash in circulation is used for anonymous stores of value and illicit transactions. Some stats: nearly 80% of the currency in circulation is in $100 bills, enough for every American household to inventory over $1000 at a time. Estimates indicate more than half of US physical currency is actually held abroad:

https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/ifdp/2012/1058/ifdp1058.pdf