Potential pathways for higher yields

13/09/2018

Andrew Norelli

If the Three Phases Model turns out to be an accurate-enough framework for market dynamics during 2018, then longer-term interest rates will rise in aggregate over the course of the year. Not in a straight line though, but rather in a sine wave higher, then lower, and then higher once again. In many ways this feels like an unsatisfying way to get higher rates, and it probably doesn’t lead to dramatically higher yields anyway.

Yet I and many of my fellow market participants seem to feel intuitively that rates should be higher. In the old days, if we had the level of growth the US is currently enjoying, 10-year Treasury yields would be higher than they are now. This intuition is supported by quantitative models also, for example the Taylor Rule, the Nominal GDP versus 10-year yield linkage, and the ACM term premium model all suggest rates are far too low. When you couple the intuition with the math, and layer on top the obvious increase in Treasury supply from the budget deficit and Quantitative Tightening, it feels downright weird that Treasury yields aren’t higher.

Much of my constructive view on rates (during Phase 2) has been rooted in the idea that because potential growth is slow, the labor market is tight, and the fiscal stimulus is ill-timed, monetary policy should welcome tighter financial conditions explicitly to slow down realized growth. Unless and until financial conditions begin to materially impact the economic data, the Fed should and would act to constrain inflation pressure. In practice, that meant continuing gradual hikes and balance sheet reduction. This leads to a flatter curve and weak-ish risk markets, together with anchored inflation expectations and long-end rates (Phase 2).

The nagging feeling in the back of my mind remains constant though, that rates should be higher intuitively. So I am continually vigilant for what sequence of events from here could lead to durably higher long term rates. Some of these I’ve mentioned in this forum over the past year, but my current list is:

- Evidence that the accumulated effects of monetary policy tightening to date, inclusive of balance sheet reduction, are slowing the economy toward its potential growth rate unnecessarily quickly. In order to maintain its shot at an eventual soft landing, the Fed pauses, allowing risk-on sentiment to fully swing back into markets (not just in US equities). This results in a bear steepening, with the front-end of the curve anchored by low policy rates, but long-term Treasury yields going higher through both real rates and break-even inflation rates. When the Fed takes a pause, ultimately it lifts the market expectation of terminal policy rate to something restrictive rather than neutral, and also pushes out in time the end of the tightening cycle. Term premiums also expand as global risk aversion abates.

- A durable surge in labor productivity, which would lift the potential growth rate of the US, while the realized growth rate can maintain the stimulus-fueled lofty levels. The gap between these two growth rates when the economy is at full employment represents inflation pressure, so shrinking the gap reduces inflation pressure, all else equal. In response, the Fed can slow down their tightening process, but ultimately arrive at a higher terminal rate because higher potential growth rates should allow higher equilibrium policy rates. The curve bear steepens in this case, led by real rates (as opposed to break-even inflation rates).

- If the Fed encountered a surge in inflation and actively chose to ignore it, intentionally opting to let the economy run hot. The Treasury curve bear steepens here too, but this time, it’s led by break-even inflation rates while real rates and the front end remain anchored by low policy rates. Alternatively, an inflation spike which triggers an appropriately aggressive Fed response results in a flatter curve, but whether the 10y yield goes up or down is less clear.

- If President Trump were to succeed in influencing the Fed to hold policy rates too low compared to what would be necessary to maintain their 2% Core PCE inflation target. In this case, the price stability mandate is compromised. So far there have been at least 1 tweet and 2 interviews in which he expressed “[t]ightening now hurts all that we have done.” This results in a bear steepening also, led by breakeven inflation rates with the front end artificially anchored.

- If the President via the Treasury were to actively intervene in the foreign exchange market to devalue the dollar, and/or purchase non-dollar securities. Same thing – bear steepening as inflation expectations become unanchored, and Fed loses one key element of financial conditions policy transmission mechanism: the free-float exchange rate.

The key theme is that all of these cases involve the central bank leaning dovish, whether that’s justified or unjustified, intentional, or unintentional, which all together is a bit of a paradox. It’s much easier intuitively to link a Federal Reserve aggressively hiking rates with a higher 10y yield, but at this point, given what’s already understood in the market about US growth and the supply/demand dynamic for Treasurys, I think it is actually dovish policy of some kind which will ultimately lead to higher rates. A subset of this has been a key element of the Three Phases Model – in Phase 3 we expect higher Treasury yields concurrent with a dovish course correction which most closely resembles item 1 in this list. But durably (and significantly) higher 10-year yields probably require at least one of these 5 circumstances, or something similar.

Rewind to August 24, 2018, Jackson Hole, WY. Fed Chair Jerome Powell gave a speech entitled Monetary Policy in a Changing Economy, which included a number of debatable and dutifully balanced passages. However, I cherry picked the following quotes and generally saw the speech as unnecessarily dovish:

“Under Chairman Greenspan’s leadership, the Committee converged on a risk-management strategy that can be distilled into a simple request: Let’s wait one more meeting; if there are clearer signs of inflation, we will commence tightening. Meeting after meeting, the Committee held off on rate increases while believing that signs of rising inflation would soon appear. And meeting after meeting, inflation gradually declined….

“In retrospect, it may seem odd that it took great fortitude to defend ‘let’s wait one more meeting,’ given that inflation was low and falling. Conventional wisdom at the time, however, still urged policymakers to respond preemptively to inflation risk…

“While inflation has recently moved up near 2 percent, we have seen no clear sign of an acceleration above 2 percent, and there does not seem to be an elevated risk of overheating. This is good news, and we believe that this good news results in part from the ongoing normalization process.”

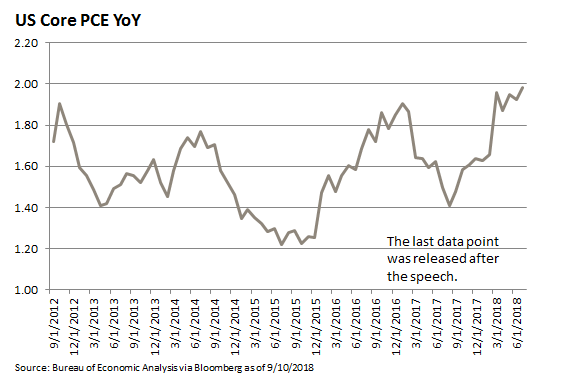

For now anyway, inflation seems to be in the eyes of the beholder. Given what could be said about the chart below and whether or not Core PCE is accelerating, and explicit references both to Greenspan’s fortitude in not hiking rates and an explicit lack of overheating risk, the speech looked dovish to me. It had elements of items 1 and 3 from my list above, and maybe even a hint of number 4.

For these reasons, I viewed the speech as a short-term bearish signal for Treasurys and I think Powell’s remarks more than any other catalyst are what sent 10-year yields back toward the high end of the range in recent days. However, it’s just one speech, and I don’t think any of my proposed pathways to higher rates have been definitively satisfied. The average hourly earnings data last week offered more evidence that a dovish course correction is not yet justified by the data, and the Fed should see it that way. So, structurally, I think we’re still in for more Phase 2 price action: weak-ish risk markets, stronger dollar, and range-bound-to-lower yields. The recent market response to Jackson Hole merely lends some credence to the idea that dovishness of some kind would be the current pathway to higher yields.