MMT: short-term gain vs. long-term pain

21/03/2019

Ed Fitzpatrick

Kelsey Berro

Why is everyone talking about Modern Monetary Theory (MMT)?

Let’s set the scene: starting first at the Capital building, the newly elected Congress is proposing fiscal initiatives aimed at improving a variety of factors, most notably income and wealth inequality, which are projected to further balloon already large government deficits. Over at the Eccles building, the Fed is keeping interest rates on hold and simultaneously working through their first ever formal re-evaluation of their longer-term policies, tools and communication framework. The combination of the Fed on hold and an evolving populist political agenda has given rise to a reconsideration of formerly fringe economic theories.

What is MMT?

Don’t let the name fool you. MMT is not modern and it is not a theory. MMT is the financing of government spending by expanding the monetary base (i.e. printing money) through accounting channels. This concept has been around longer than modern-day money has existed and governments have attempted to do it in one form or another going back to Babylon. Advocates of MMT view the currency of the US as a public good rather than a medium of exchange which should be used to achieve full employment. MMT also believes that the central bank is an extension of fiscal policy rather than an independent entity. MMT allows for potentially unlimited government spending premised on a national savings account relationship with inflation as the only constraint. There are other caveats and assumptions within MMT to bridge the gap between theory and reality but in the end it relies on a level of fiscal and monetary calibration that has never existed. Leaving aside the implementation challenges and the risk of overemphasizing the results of econometric modeling over reality, in this blog we focus on the practical costs and benefits of such a policy. While attempts at money printing have stood the tests of time, MMT applied to today’s world will need a more nuanced approach given recent developments within the financial system, fiscal and monetary policy. While it may be unsustainable for a country to finance deficits through money printing, the path in which a country reaches a tipping point varies. Focusing on application in the US, current economic conditions and structural attributes of the economy may not lend themselves well to other popular comparisons of MMT “success” (such as Japan – but more on that later).

What are the benefits?

Because MMT is only expected to be bound by inflation it has maximum flexibility to address any shortfalls in economic activity as well as address potential growth prospects. Ideally under MMT, the government is expected to spend sufficiently enough to achieve full employment without the constraints of funding this goal. In this framework, there is no difference between the central bank and the Treasury, so new spending is just a liability on the overall public balance sheet without a corresponding asset. When the outstanding stock of debt needs to be refinanced the Fed will step in. Advocates argue that higher deficits will not impact interest expense and will not crowd out private sector borrowing because the Fed will finance Treasury debt at any price therefore keeping real yields very low and diverting investment from the public to private sector, provided inflation is contained. If the fiscal spending is targeted appropriately to the correct initiatives (think infrastructure, education, etc.), the spending can improve the supply-side of the economy, improve growth potential and allow the debt (“in this case liabilities”) to GDP ratio to stabilize through stronger growth although this is a secondary factor. Put more simply, advocates believe that MMT maximizes social good, pays for itself through improving potential growth and says deficits don’t matter since they don’t differentiate between public liabilities. So, what are the downsides to this policy?

What are the costs?

The three principal pushbacks to MMT tend to be oriented towards negative outcomes in the long-run: 1) debt unsustainability 2) out of control inflation and 3) financial instability.

On the debt sustainability issue (or perceived lack thereof), the US does not have a particularly good track record of remaining disciplined with its spending once it starts. Historically, increases in deficit spending used to make up for a short-run growth deficiencies, like a recession, have resulted in decades of incremental spending even after the economy has fully recovered. The Budget Control Act of 2011 was the last time fiscal spending was capped and since 2013 those caps have been annually adjusted higher, most recently in 2018. If cutting spending isn’t feasible then raising taxes is the only other alternative. In MMT, only the growth side matters while deficits are irrelevant as long as inflation is benign. Supporters argue that there can’t be a crowding out if the Fed keeps real yields low but this is a circular argument because it works until it doesn’t.

Consider the impact to the Fed’s objectives if they commit to funding government deficits. This would imply that the Fed can no longer respond to inflation and unemployment unless we are in a recession. Committing to funding deficits would hinder their credibility, independence and ability to achieve their congressional mandate. Going even further, by sacrificing their inflation credibility to fund deficits the Fed risks unanchoring inflation expectations causing realized inflation to rise. Remember, MMT cannot work if inflation becomes a problem and under this scenario the Fed’s deficit funding will override its objectives to manage inflation and they will be unable to stop inflation from spiraling without taking policy action that would either slow growth or raise interest rates (both results being counter to the objectives of MMT).

Additionally, despite the US being a relatively closed economy, it still runs a trade deficit which means we rely on foreigners to recycle the dollars we spend buying foreign goods. With the prospect of higher fiscal deficits and more money printing, investors should require a higher rate of return on their investment. But since the Fed is holding down yields, the main release valve becomes the USD. Significant weakening of the dollar means imported goods would rise substantially in price. Normally this would be offset by lower demand but the MMT process is there to offset the weakening in demand by throwing more spending at it. Hence, MMT spending may solve the demand problem and keep rates low but it does not solve the inflation problem. As we have now discovered, the inflation problem associated with MMT could be dramatic as a result of both a weaker currency and a Fed that’s price level stability objective is no longer credible.

Once inflation really starts to take off there are only really two solutions: 1) higher taxes or 2) accepting higher inflation. While higher taxes are expected to be used, the political willingness is questionable, as is the effectiveness. There is a third but really not relevant alternative being touted by advocates. The assumption is that policymakers (through the CBO) can isolate the fiscal initiatives that are causing inflation and redirect that spending to other initiatives. Perhaps this is the truest crux of the MMT discussion. Can one group of individuals be entrusted with the authority to know the appropriate level of stimulus in a dynamic economy, respond quickly enough to recalibrate policy when it is wrong and avoid political pressures while making those decisions? Perhaps, if the authority was independent, but we have already established that the independence of fiscal and monetary decisions needs to be compromised for MMT to work.

Even if MMT was perfectly calibrated to keep the dollar and inflation stable, the final cost to MMT is the risk around financial stability. Building debt loads and rising leverage builds the foundations for a vicious asset price cycle. Boom/Bust asset price cycles have become so ingrained into our economic reality that perhaps they don’t seem like a cost anymore, but each boom and bust is met with more debt and more vulnerability.

Is MMT similar to QE?

Sort of, but again the nuance is important. At the heart of the discussion is the independence of the Fed as well as its congressional mandates. The distinction between MMT and QE comes down to intent. Currently, the Fed adjusts the monetary base to meet its objectives of price level stability and maximum employment. The Fed’s monetary policy operates independently of the Treasury’s financing needs. More recently, the Fed has been raising rates and shrinking the monetary base while deficit spending has been rising. In contrast under an MMT framework, the Fed would explicitly finance the deficit, matching or exceeding their quantity of purchases to mirror the deficit forecast. The financing costs on the outstanding stock of debt would rise and the Fed would need to intervene. A consequence of this policy would be a crowding out of private investment. In comparison, QE was aimed at increasing private investment through cheaper cost of credit for consumers and businesses. QE is also aimed at stimulating growth and higher inflation while MMT aims to stimulate growth without stoking inflation.

Is Japan a proper comparison?

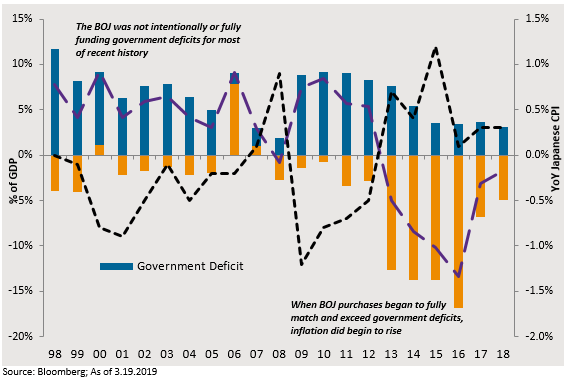

Japan has a tremendous debt to GDP ratio (over 200%, – more than double the US) yet their interest rates are very low, in some cases negative. Japan currently runs a fiscal deficit and has recently engaged in QE purchases which are greater than their fiscal deficits. So this is proof that deficit financing through printing money is possible. Over this time, inflation has remained exceptionally low. This is where the similarities to MMT end. Japanese fiscal deficits have remained fairly stable at ~3.5% of GDP, so there hasn’t been incremental fiscal spending as proposed by MMT, rather maintenance of the existing pace of spending. So this is really monetary policy QE stimulating growth rather than a true coordinated MMT. Although Japan has kept interest rate policy low since the turn of the century, the QE experiment (not MMT) has only just begun and the ramifications further down the road are still unknown. More recently, Japanese inflation has moved from negative to positive for the first time in decades and their currency has also weakened noticeably after the introduction of QE in 2013 (see chart below).

Could the Japan experience work in the US? Unlike Japan, US has a negative current account balance, a growing fiscal deficit and a structurally different economy (the US population is still younger and our labor force growth still faster than Japan). In addition, inflation in the US is already running near 2% while inflation in Japan has been benign for much longer.

Why now?

The scars of balance sheet recessions, as discussed by Rogoff and Reinhart, still linger in relatively low growth, low inflation and uneven benefits during this lackluster recovery in the US. As R&R highlighted in their seminal work, balance sheet recessions take a long time to adjust and fade into memory. We are approaching the 11th year following the crisis, not yet fully past the long-lasting impacts of a deep recession. In an attempt to explain and counteract the post-crisis malaise more ammunition has developed in favor of MMT than perhaps ever before:

- The modest economic recovery in the US has not been strong enough to disprove secular stagnation theories.

- Secular stagnation was a theory reintroduced by former central bankers and academics nearly a decade ago and the remedy calls for higher fiscal spending. This theory has gained credibility as growth has remained lower than pre-crisis. Global central banks have had only limited success in their ability to remove accommodation without negative consequences.

- Japan has evolved to be a great test case.

- With a debt to GDP ratio of nearly 250% sustainability has not been an issue. They have also proven that QE works to finance debt.

- The FOMC has affirmed that the US has no inflation problem.

- The Fed has recently proclaimed inflation too low and at risk of falling further despite a tight labor market and above trend growth.

- In addition, in an effort to spur inflation the Fed has prioritized asset prices over financial stability.

- The Fed has recently proclaimed inflation too low and at risk of falling further despite a tight labor market and above trend growth.

- Populism is gaining ground in electoral representation.

Between fiscal and monetary policy makers here and abroad, the rise of populism and the focus on short-termism, it becomes clear why MMT is part of the recent discussion. The short-term benefits appear to accrue to everyone without any costs.

Conclusion

It is easy to see why MMT is so appealing; there are only benefits and no costs to implementing in the short-term. With growth and inflation in the US still less dynamic than imagined compared to the pre-crisis experience, fresh thinking on solutions to improve the economic outlook and productivity are appropriate. MMT provides a thought-provoking lens for addressing structural economic challenges. But MMT it is not a panacea as one or more of the following fragilities in the theory will inevitably break: 1) debt sustainability, 2) the dollar’s store of value 3) inflation 4) financial stability. You can get away with MMT for some time, maybe even a while. Japan has proven that large debts partially financed by central banks has not yet lead to a collapse in currency or a rise in inflation, but the jury is still out. To us, Japan looks more like QE than MMT, but even if you disregard the nuances of the comparison, the experience of Japan is hard to parallel to that of the US. Japan started from a more advantageous place on inflation (it was negative) and its balance of payment (which remains positive) compared with the US where inflation is already around 2% and trade deficits are ever increasing. This would not appear to be the time to start with MMT. MMT in the US doesn’t sound crazy if you base your decisions on the recent past or on other country’s experiences but in doing so you must ignore structural economic differences.

While policymakers have set the stage for this type of theory to flourish, historical experiences dating back thousands of years informs us that debasing currencies and spending without care, may feel good in the short-term but it is unsustainable and usually irreversible over the longer-term.