Approaching the first intermission

26/04/2018

Andrew Norelli

Back in January I laid out a nuanced description of how I thought 2018 could unfold from a macro perspective. The dominant theme was the shift from accommodative global monetary policy to restrictive policy, and how I thought the impacts of this tectonic monetary shift would manifest in three distinct phases. While I think the skeleton of that view is still relevant and appropriate, it has been somewhat mangled by the chaotic domestic and international news flow. Some of those topics are likely to linger, others to fizzle, but generally I expect the narrative to once again coalesce around both the need for and the impact of tighter monetary policy.

The flattening of the yield curve has endured the volatile news cycle, and I think it’s instructive as to the importance of the monetary policy transition to broader markets. So, what is the relentless flattening of the curve and its current shape telling us? One potential concern is that the flattening (which obviously can presage a recession) is indicative of a policy error in the making; that the Fed is focused on steadily hiking rates in the face of exaggerated inflation risk, and is ignoring the impact of balance sheet reduction on financial conditions and/or actual inflation pressure is modest. In other words, that the ageing economic expansion is about to be killed by higher policy rates.

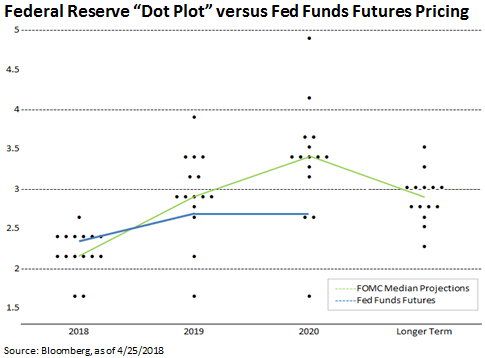

There is, however, a more sanguine way to look at it: that the market is appropriately pricing in an optimistic outlook for a soft landing, which is more consistent with the message from risk markets. Frequent readers will know that I believe the labor market is tight, that moderate inflation pressure is building (the realized inflation data is clearly trending higher on shorter dated moving averages), but I also believe that so far there has been no obvious uptick in labor productivity. So, potential growth is still slow at about 1.5-2%. In this sense, the economy is growing too fast to avoid higher inflation given its full employment constraints. Therefore, central bankers actually need the economy to slow down. In my view, a combination of 2-3 more hikes this year, 1-2 next year, and accelerating balance sheet reduction (QT) this year will be sufficient to tighten financial conditions enough to slow down realized growth to around a 2% run-rate by mid-2019 (only a year away!). If the Fed can engineer this, unemployment hovers around 3.5%, and the 1.75-2% growth is sustainable until some eventual exogenous shock happens. Would you be surprised if the Fed hiked rates 4-5 more times and stopped at around 2.75%? This is essentially in the price:

It’s also noteworthy that the market is not pricing a terminal rate much above neutral, suggesting optimism that the Fed won’t need to tighten much into contractionary territory.

The “Three Phases” macro model of 2018 would more-or-less jibe with this current interest rate pricing and potential evolution of the data. Hypothetically, Phase 1 is a period of tightening financial conditions as all markets begin to anticipate asset price inflation running in reverse with QT going global in October. With liquidity withdrawal taking place, investors proactively hold a bit more cash and buy a bit less non-cash assets; and lower stocks, wider spreads, higher rates, higher volatility, and a stronger USD ensue. In Phase 2, the lagged impact of tighter financial conditions starts to show up in the real economic data, and while risk assets remain weak, rate markets are firm as the market anticipates the inability of the central banks to return to “old normal” levels of policy rates. And then in Phase 3, central banks recognize the convergence of realized and potential growth rates, and telegraph less aggressive policy normalization. Soft landing ensues.

Q1 2018 had a Phase-1-type feel to it, especially on certain days. It wasn’t a perfectly uniform financial conditions tightening because the dollar was weaker, but everything else was in the tighter conditions direction. It also wasn’t purely driven by falling liquidity, which was my expectation, but instead the cacophony of domestic and international headlines ultimately drove markets weaker. The economic effects of tighter financial conditions ought to be agnostic to the source of market weakness though, and liquidity withdrawals should be an ongoing headwind for the entire year. So, my base-case expectation is that Phase 1 was pretty mild so far but it may get a little more intense here in the middle innings, especially if the dollar begins strengthening with higher interest rates. This directionality between FX and rates started to occur in recent days while stocks and credit traded weaker, such that all 5 financial conditions components were tighter. As Q2 passes, the data may underperform expectations and this’ll be Phase 2. If expectations of economic performance are unchanged from levels immediately following the tax bill and budget deal passage, the accumulated impact of tighter financial conditions is likely to put the brakes on, to a degree. The data ultimately isn’t weak necessarily, but it’s just not as strong as anticipated. Think 2.7% (and declining) run rate rather than 3+%. Then, in Phase 3, the Fed communicates an acknowledgement of tighter financial conditions and steers policy expectations toward a slower path of normalization. Risk assets rally back and the curve steepens somewhat.

This description of the way I envision markets digesting the shift to tighter monetary policy still ultimately depends on several critical variables which are unknown. Will productivity rebound and lift potential growth? See: The Shadow Productivity Escape Hatch. Is the equilibrium real policy rate (r-star) returning back to pre-crisis levels, such that more than 5-6 hikes plus accelerating QT will be necessary to avert inflation? Will the Fed actively tolerate above-target inflation and try to justify it as transient? Any one of these can lead to still-higher long-term Treasury yields and disrupt the “Three Phases” model. Or alternatively, if the lagged impact of existing hikes and liquidity drain via QT and slowing credit creation means the current policy rate pathway is actually too aggressive, then rates are peaking now. Regardless of the answers to these questions, realized volatility in all asset prices should continue to be elevated as markets adjust in fits and starts to the new reality of liquidity removal. We’re positioning portfolios to benefit from higher volatility itself, as well as reallocate opportunistically as asset prices fluctuate.