An inadvertent reprieve

15/06/2017

Andrew Norelli

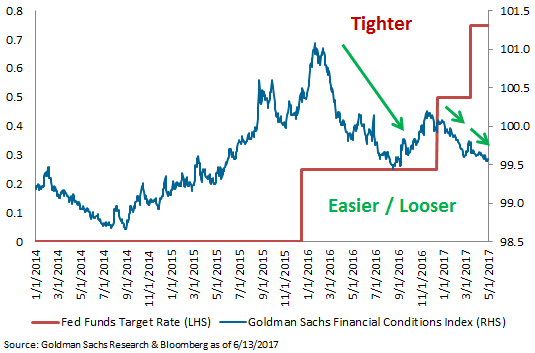

Financial conditions, broadly defined, reflect the cost for consumers and corporations to obtain financing: equity or debt, domestic or foreign. Those costs are primarily driven by market forces, and financial conditions remain the primary transmission mechanism for monetary policy to affect the broader economic fundamentals. So, policy and economic performance are inextricably linked by markets. Perhaps it’s strange then, that the Fed has tightened policy rates four times now, and financial conditions have gotten incrementally easier/looser each time. How should we interpret this?

The reason to tighten interest rate policy is to suppress inflation pressure, i.e. to intentionally slow down an economy which is operating faster than its long-run potential growth rate to avoid inflation at full employment. The Fed has been in a tricky position the past 18 months or so, because long-run potential growth in the US remains low (around 1.5%) so the realized growth rate of only around 2% is high enough to theoretically create inflation pressure, but also low enough to periodically appear fragile and vulnerable to over-tightening. As the unemployment rate continues to fall, economists see confirmation that potential growth remains annoyingly slow, but also are suspicious that inflation pressure should be just around the corner. This dichotomy creates competing concerns that the Fed might risk economic performance by overtightening, or risk losing control of inflation by tightening too slowly. Noise in the real-time data encourages sentiment to shift between the two.

I see two ways to view financial conditions easing during Fed policy rate tightening, and the oscillating sentiment surrounding the current dominant policy risk (too much vs. too little tightening) basically determines the prevailing interpretation. If inflation pressure is right around the corner, then the risk is the central bank is tightening too slowly, and loosening financial conditions would be basically unacceptable. The central bank must slow growth to below long-run potential in order to avoid inflation, and tighter financial conditions through some combination of higher rates, wider spreads, lower equity prices, and a stronger dollar is the way to do it. If, however, the prevailing analysis and sentiment is that inflation pressure is under control, then loosening financial conditions during a Fed tightening regime is remarkably desirable. All else equal, higher policy rates provide the central bank with more flexibility to respond if and when economic growth slows and the unemployment rate turns higher. If the Fed may raise rates without adverse effects on financing costs (or even with improvements), then the committee is strategically in a less confined position.

It turns out that the last three inflation reports in the US have indeed swung sentiment surrounding inflation pressure in the US back toward something more sanguine. As luck would have it, one-off statistical adjustments reflecting better quality of unlimited data mobile phone plans, and moderating healthcare inflation, created two months of soft numbers. In fact, the cell phone effect resulted in an outright decline in the core price level, which will optically reduce the year-on-year inflation numbers for the next nine months into the future. Whether one should view year-on-year inflation statistics as the most important indicator of inflation is doubtful, but they are nonetheless a critical component of the narrative on inflation in the US. Those stats, and the Fed, have just gotten a reprieve. At the same time, growth statistics are still expected to bounce back from a weak Q1, to continue to reinforce the noisy-but-basically-stable 2% growth rate. It’s still above potential, and not so slow as to require a pause in hikes or easier monetary policy.

So, all of a sudden, loosening financial conditions in the face of policy rate tightening is a good thing, not an indicator of a central bank who might be under-delivering on policy tightening.

Additionally, the roughly $150 billion per month of continued Quantitative Easing in Europe, Japan, and the UK has provided some buoyancy to both risk markets and interest rate markets, further easing financial conditions in the US all else equal. The recent weakness of the US dollar (and corresponding strength in the euro and yen) has given those foreign central banks some incremental room to continue those policies.

This backdrop comprised of easing financial conditions under steady policy rate hikes, with inflation concerns relegated to the back burner, and growth rebounding but not altering the 2% average run rate, is one which continues to support positions in credit risk and EM. Cynically, it could be described as more “muddle through,” and though muddling through is insufficient to address systemic challenges in the US economy and society discussed here in the past, it should be good enough to sustain investments which provide excess carry and income. This has, after all, been the character of the post-crisis recovery more often than not.