As the fear of economic recession recedes on the back of stabilization in economic data and the signing of the “Phase One” U.S.-China trade agreement, investors are now asking whether inflation could return, threatening the rally in financial markets. Given the very low unemployment rate in the U.S., one concern is that companies will start to pass on the higher costs of labor and other inputs to consumers. This could force the Federal Reserve (Fed) to reverse course and raise policy rates.

There is no denying that the U.S. labor market remains tight. Despite the relatively soft December non-farm payroll data, underlying demand for workers is solid. However, the year-over-year change in average hourly earnings has started to decelerate after peaking in October 2019. Given strong U.S. corporate profitability, employers have been able to absorb these higher costs in the past, and this could continue in the near term. This implies that U.S. core personal consumption expenditures (PCE) deflator, the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, should remain below the 2% target. The Fed’s own projection is for PCE inflation to stay around 2% between now and 2022. While there are cyclical fluctuations, it is the long-term structural factors that really subdue the inflation outlook—aging demographic profiles in the U.S., technological developments that keep services cheap, stronger financial regulation on banks and higher savings rate by consumers after the Global Financial Crisis.

What could go wrong and drive inflation higher? Geopolitical conflict in the Middle East pushing energy prices significantly higher would raise headline inflation, but at the same time take away disposable income from consumers. A significant deterioration in U.S. trade relationship with key partners leading to surge in tariffs would also push up the costs of imported goods. In these scenarios, the Fed is much more likely to stand ready to provide more stimulus to counter slower consumption, not raise rates to suppress inflation.

Another possibility is for a populist shift in U.S. politics and for the administration, current or future, to run persistent fiscal deficits to address inequality, and rely on the Fed to employ quantitative easing to fund this spending. Greater fiscal resources to the lower income group could provide a strong boost to the economy given their high propensity to spend, and hence generate more demand-side inflation. This scenario does not look likely in the foreseeable future either. We continue to expect the Congress to stay divided after the November elections, with the Republicans and Democrats to retain their majorities in the Senate and House of Representative respectively. This setting makes drastic shift in fiscal policy almost impossible.

Overall, the risk of inflation surging is manageable. Moreover, Fed Chair Jerome Powell has emphasized that the 2% inflation target is symmetric. Given inflation has run below target for an extended period of time, the central bank could become more tolerant of inflation, allowing it to climb above target for a while. It could show a greater sense of urgency to deal with downside risk to growth, instead of inflation, as we saw in 2019.

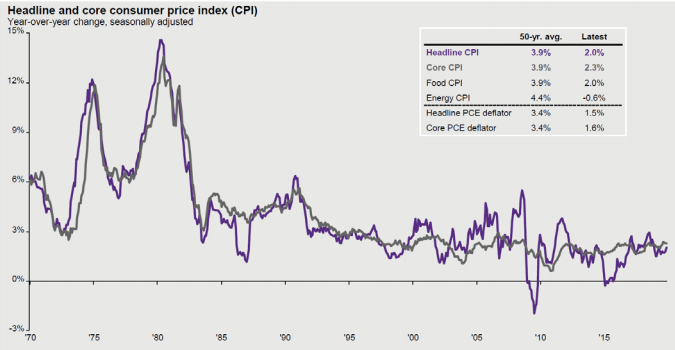

EXHIBIT 1: UNITED STATES: INFLATION

Source: Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of Labor Statistics, FactSet, J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Core CPI is defined as CPI excluding food and energy prices. The Personal Consumption Expenditure (PCE) deflator employs an evolving chain-weighted basket of consumer expenditures instead of the fixed-weight basket used in CPI calculations. Latest inflation numbers are November 2019 for CPI & sub-indexes and for PCE deflators.

Guide to the Markets – Asia. Data reflect most recently available as of 31/12/19.

Investment implications

Inflation concerns partly explained the market volatility in early 2018, which saw a spike in U.S. Treasury yields and sizeable correction in global equities. We believe that the fundamental inflation drivers in the U.S. remain benign at this point, especially taking into account the structural factors keeping prices in check. More importantly, the Fed should remain patient in the face of rising prices and not rushing into raising policy rates. This implies any negative reaction from the market on inflation worries is likely to be temporary. A steady Fed should anchor the short end of the yield curve, and ongoing improvement in global growth could drive the long end higher. This curve steepening could benefit the financial sector, including banks and insurance.

The greater bias to address downside risk to growth by the Fed should also be supportive of emerging and Asian markets. Central banks of South Africa and Turkey have already kicked off 2020 with rate cuts. We expect more monetary easing from emerging market (EM) central banks to come, especially if the U.S. dollar remains steady. This would benefit both EM/Asia equities and local currency emerging market debt.

0903c02a827d9e94