Hear more on market conditions that have contributed to strong private equity performance in recent years, and the value that a PE allocation can provide in the decades to come.

[MUSIC PLAYING] Welcome to The Center for Investment Excellence, a production of J.P. Morgan Asset Management. The Center for Investment Excellence is an audio podcast that provides educational insights across asset classes and investment themes. Today's episode is on private equity and has been recorded for institutional and professional investors.

I'm David Lebovitz, Global Market Strategist and host of The Center for Investment Excellence. With me today is Jared Gross, Head of Institutional Portfolio Strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Welcome to The Center for Investment Excellence.

Thanks for having me.

Well, Jared, I know you've recently released an Allocation Spotlight piece talking about private equity and I know we're going to have an extended conversation about private equity here today. But before we kick off, I just wanted to give you a chance to talk a little bit about your thoughts and what you covered in that piece. And again, I know we're going to unpack it in more detail, but kind of the idea behind writing these allocations spotlight pieces and what you hope to tackle in them going forward.

Yeah. Thanks, David. Well, the Allocation Spotlight is really intended to provide a focused discussion of a topic related to strategic asset allocation for institutional investors. And over time, the topics will move around the portfolio from traditional liquid market assets, to alternatives, and various other topics, but the most recent topic was private equity.

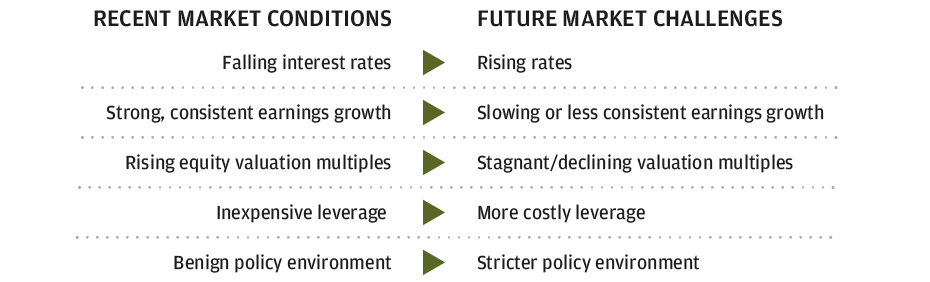

And specifically, what I was thinking about was the extent to which the economic environment that we've have been living through for the past 10 years or more has provided a tailwind to private equity. And obviously, that's good for investors. We're happy to see positive returns coming from this asset class. But it also raises a potential concern that in the event that some of those tailwinds change and the market environment evolves, so that perhaps they are less powerful as a source of returns or even become headwinds and make it more challenging for private investing, how should investors think about that?

And when you think about the level of liquidity in the financial markets, you think about the declining levels of interest rates, and the cost of leverage that creates, you think about the rising equity multiples that we've seen and what that does for the exit valuations of private companies, all of those things have been very positive. And while we're not predicting a immediate turnaround in any one or all of those factors, we do have to recognize that interest rates have probably touched the lows and are now rising, that equity valuations are high and will probably struggle to go higher, and that liquidity is probably at its high point. And to the extent that the Fed begins pulling back at some point in the next year, or two, or three, those conditions will seem to be less benign. And so within a private equity investment universe, what do you do with that?

Well, we don't want to be overly prescriptive, but what we would suggest is that strategies involving smaller to mid-size opportunities where the general focus of the investment is tilted towards operational improvement, cash flow generation, and what we would call bottom-up value creation as opposed to leverage and maybe some of the more financial engineering style of value creation, those kind of smaller to mid-sized opportunities are probably going to do a little bit better. And of course, from an investor's standpoint that is good, but it's also a challenge, because that's a more difficult market to access. The private equity universe is very broad. There's a lot of managers out there. The selection is a challenge.

If you look at the top quartile versus bottom quartile, a lot of the top quartile managers are in this small space, but so are a lot of the bottom quartile managers. And so it really requires some handholding to do this right. And so the conclusion is really that we want to be probably tilting towards the kind of smaller end of the spectrum and looking for ways to get helpful advice, either through consulting or a direct private equity fund manager who can deploy their skill on an investor's behalf in that space.

I think that those are all great points and I know we're going to unpack them in a little bit more detail over the course of our time together here today. But before we talk about what some of the challenges that private equity may face are going to look like going forward, maybe we take a step back and just think about, as private equity as an asset class has had the wind at its back, what is the role that it's played in portfolios? And I know you talked a little bit about the way that value may be created going forward, but over the past couple of decades, how have you seen value be created within the context of various private equity strategies?

Let me start at the highest possible level, which is private equity is in portfolios to generate high returns, full stop. It's an asset class that bears relatively high fees and has relatively low liquidity. So we wouldn't use it if it didn't provide an exceptional level of performance over the opportunity set that is available in the more traditional liquid markets. And the good news is, it has worked.

Private equity has delivered. So returns have generally been significantly higher than public market equivalents, if you want to look at the S&P 500 or some other market benchmark that you can use as a proxy. I think what has taken place in portfolio construction at the strategic level is the alternative asset class space has evolved from maybe initially more focused on real estate, than ultimately private equity was added, then hedge funds. Now we're moving more into private credit and core real assets and the opportunity set expands.

I think one of the things we have to observe and be a little careful about as investors is that we don't allow the modeling of portfolios to drive allocations to places where they shouldn't be. And what I mean by that is, private equity has to be very blunt about it, benefited from some flawed modeling expectations, particularly around volatility. And so when we look at an asset class that has exhibited very high historical returns and relatively low realized volatility, it obviously models well and that has been very supportive of including private equity in strategic asset allocations. And I think a lot of people have noted this fact and have observed that the volatilities are probably held artificially low by virtue of the fact that the assets themselves are not marked to market in anything close to real time, and that is both a concern but also a real benefit in that the portfolio does not exhibit volatility in the short term.

So I think when we think about the broad alternative category, private equity certainly stands at the kind of extreme end of the return spectrum. We probably have to recognize that there's a bit more volatility in it than the realized volatility of the assets themselves has shown. And some of that comes from manager dispersion where a bottom-quartile manager and a top-quartile manager will exhibit extremely different performance results.

But basically, it is entrenched as an asset class. I think the opportunity set continues to grow. The scope of managers of the sectors and industries that they're active in, the diversification of the underlying assets that are being held in these funds, the use of co-investments, secondaries, venture, it is a very deep and rich asset class that is absolutely essential to generating high long-term returns in the current market environment.

I think that those are all really key points. And obviously, like I said earlier, private equity has very much had the wind at its back over the course of the past couple of market cycles. But what's really coming into focus from where we sit is what that's going to look like going forward. And we had a Fed meeting last week. We, obviously, got a series of updated projections in terms of what they think economic growth, and inflation, and interest rates are going to look like here going forward.

And I would say that we talk a lot about marking things to market in the private investments world. And it kind of felt like the Fed marked their forecasts to market when they got together last week, now showing two rate hikes, economic growth, which is set to be more robust than was initially forecast, and inflation, which actually may prove to be a bit stickier than what a lot of people had originally thought. And what I would say here is that we're still very much of the view that the increase in rates is going to be gradual, right?

We're talking about 2 rate hikes over the next 2 and 1/4 years. We're not talking about rate hikes over the next three months. And we do think that the inflation that we're seeing in real time and that we'll see through the end of 2021 and into 2022 will, in fact, prove to be transitory.

But we are beginning to think about inflation in a little bit more of a balanced way. And I think that as we kind of began to come out of the pandemic, very much of the view that inflation was going to be driven by a reopening of the economy, elevated airfare prices, elevated hotel room prices, everybody wanting to go out to dinner and that mismatch between supply and demand, resulting in a bit of inflation, but we thought that it was going to be transitory. And what I would say is that the big risk to inflation being transitory in the current environment, I think, really comes back to the issue of wages. You're getting to see private sector companies on their own increase the wage that they pay their lowest wage employees.

And so absent some mandate from the Federal government, you're beginning to see wage growth materialize at a time where I think a lot of people expected it to be subdued, given the compositional shift that occurred as the pandemic took hold. That pushed wages higher. People thought that as lowest wage workers came back in, that was going to lead wage growth to be soft, and that's just not what's playing out. And so I think what we need to focus on as investors going forward, as it pertains to the outlook for interest rates, which is obviously integral to the thesis around private equity over time, is what happens with wages?

And do we see more robust wage inflation certainly than was observed during the prior cycle? Because I think that if we do, that kind of puts this idea that the Fed is going to be able to take their time and rates are going to go up very gradually, add a bit of a risk. And so if this backdrop changes very quickly, again, I think it's reasonable to expect that some private equity managers may find themselves in a little bit of a tough spot, particularly given that when they are raising a fund, they're thinking about the next 7 to 10 years. And so it's not what's happening today, it's the way that things are going to play out over time, which is really going to matter the most when all is said and done.

And so I'd be curious to hear your thoughts on how you think about investing in private equity in the context of market cycles. I think then we'll move on and talk about it in the context of individual companies and their lives. But from a business cycle standpoint, how do you think about putting money to work in private equity to avoid some of those pitfalls that very well may exist if the inflation story that everybody is telling ends up being a little bit misguided?

Yeah, that's a great question. I mean, on some level, we can take the easy way out and just say that if you're going to be a perpetual investor in private equity, the money that goes in today may experience a different environment than the money that goes in 3 years from now, and 5 years from now, and 10 years from now, and so on, and so on, and so on. But we do have to be, I think, a little more focused on not just the current environment, but as you said, money that is being allocated to a private equity fund today will be invested over a 3 to 5 year window and will be harvested on the back end of that, sometimes 10 years and more out.

And so when we are at an inflection point in the market cycle where rates, again, have probably bottomed and are going to be heading somewhat higher, where inflation may be spiking, that may impact the cost structure that these companies face, their ability to generate operational improvements and some of those traditional cost cutting activities that take place inside the companies at the operating level, that is something that we have to be thoughtful about. And that horizon is going to extend across probably multiple cycles. And right now, we are probably looking at a less benign environment, if not today, then two years, three years, four years out.

And I think it leads to a more interesting question that, David, maybe I'll throw it back to you, which is, as we think about the evolution of a company and its relationship to the capital raising process, private equity is one piece of that puzzle. But if you think about the scope of venture capital, and late-stage private capital, and private credit, and IPOs, and public borrowing versus private borrowing, and maybe even to take private through an LBO. There's this enormous range of avenues through which a company will interact with the capital raising process. Private equity is a big part of that, but give us some thoughts as to how you see this evolving and where there's opportunities for investors.

Well, I think that you hit on a really key point, which is companies don't need to go public the way that they used to need to go public in order to tap into various forms of financing. If you just look at the aggregate numbers, companies are staying private longer, and if they choose to go public, commanding higher valuations when they do go through that process. And so the first thing that I take away from that is, if we go back to where we started the conversation, with private equity helping to enhance overall portfolio returns, because it does give you the chance to allocate to investments and businesses during the higher growth stages of their life, what that says to me is effectively that, if you want to continue to tap into that high growth-period, you need to go private.

And so with that as the starting point, taking some of your comments into account, there are now a number of different ways that you can access that high-growth stage of a company's life cycle. You can look at things like venture capital. You can look at things like private credit, which again, a very different type of investment than private equity, but still providing those more attractive yields, and obviously, tapping into an investment universe that is far larger than what's available on the public exchanges. You've seen a lot of activity.

I think SPACs have become kind of a dinnertime conversation over the course of the past 12 to 15 months. There are different ways, different avenues that companies can tap in to financing and go public at some point, if they choose. My point isn't that going public is a bad thing by any stretch of the imagination, but more so that in order to participate in what people have gone to private equity to harvest historically, there are many different avenues that can provide that going forward. And so I do think that, obviously last year, the very robust bounce in public markets orchestrated by the Federal Reserve led to very, very aggressive IPO activity.

And you really saw sponsor-to-sponsor type transactions get kind of put on the back burner. You saw a lot of IPOs. You saw some corporate acquisitions. I think things will become more balanced going forward. But again, important to recognize that there's this wide palette of colors that companies can paint with when it comes to obtaining sources of financing. And it's not just about private equity, right?

It's about private equity, venture capital, private credit, take private SPACs. Again, the universe itself is growing in such a way that I think the really mindful private market investor needs to recognize that there are multiple avenues here that they can choose and they're going to provide very different experiences, per some of the points you were making earlier, particularly around volatility. And so with all this being said, a number of different ways that you can access these high-growth companies, the idea that perhaps the overall backdrop may be beginning to shift, particularly if inflation does end up becoming a bit of a problem, How do you think about investing in private equity today? And I know you kind of tipped your hat earlier to the idea that fund size matters, but would love to hear you just kind spell that out in a little bit more detail for our listeners.

Yeah. That's great. I think your point about inflation is key. We don't know where inflation is heading. I don't think most people feel like inflation is going to reach a wage-price spiral like we saw in the 1970s.

But it's also worth just noting that the private equity industry, for all intents and purposes, did not exist the last time we had an inflation spike. And so we don't really know how that type of investing, applying leverage, acquiring companies and waiting for an exit either into the public markets or to a sale to another sponsor, how that's going to play out. And so I do think we have to be a little bit kind of circumspect about our optimism going forward. Now, having said that, the underlying engine of value creation is relatively evergreen.

The idea that a sponsor that has talent, has management skill, has the ability to optimize balance sheets, has the ability to rationalize wages and make difficult, long-term business decisions that will ultimately add value, that is the premise on which most private equity operates. I mean, there are, obviously, more of the kind of financial engineering style of activities where it's more about adding a lot of leverage and finding ways to take cash flow from the operating business and sort of up stream it to owners. And it's not about making a value judgment across those different sources of returns.

It's really just a question of, Which of those is going to be better suited for the environment that we're heading into? And I think large firms, small firms, they all have the ability to engage in operational improvements. They all have the ability to have a patient, long time horizon over which these investments will play out. But I think it is very clearly the reality that for the larger end of the spectrum, where either the initial purchase is a take private, a traditional LBO context, or the exit is almost certainly going to have to be into the public markets, because the sponsor-to-sponsor transaction is going to be significantly larger than what you would normally expect to be able to execute, they are going to be more at the whim of these changing market valuations, whether it's the result of interest rates and leverage costs or equity multiples and exit valuations.

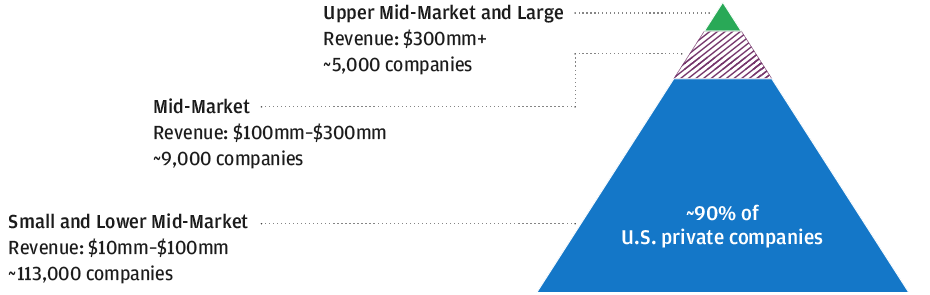

And so the safer path would seem to be staying in the smaller, midsize area where there is an enormous opportunity set. 90% of the private companies in the economy are, I believe, 300 million or smaller in revenues. And so that's where the opportunity set is. And if you're running a multi $100 billion private equity firm, it's very hard to access that and make a difference, whereas a smaller firm can find that.

And I think the other angle that I take in the paper is that the benefit of an external manager to those LPs stakes as opposed to going direct is greater visibility into the full picture, understanding industry concentrations, understanding overlaps, understanding areas where you want to have a concentration because there's a secular story about how the economy is evolving that you can take advantage of, not within one fund but across multiple funds. There's a lot of ways in which that value can be created. And I think in most instances, it's hard for investors to do that themselves.

The level of in-house expertise and due diligence required is daunting, and that's just a reality that most investors have to face up to. So keeping your portfolio invested only in the largest funds because it's a relatively manageable opportunity set is one approach, but I would argue that is ultimately going to be suboptimal. Whereas, externalizing some of that expertise into a funds manager or a private equity fund manager and letting them do the work for you is probably superior.

I think that, that makes a lot of sense. And I think to an extent, we can map that to what we've seen in public markets over time where people think about their public market equity holdings and they hold large cap US equities. They think of that as their core. They can take big bite sizes.

They can allocate insignificant amounts. But where the real alpha generation happens is in the less efficient parts of the market, right? The small and mid-cap parts of the publicly traded markets and the smaller middle market parts of the private markets as well. And so what I'm hearing from our conversation today is that private equity 30 years ago is very different than private equity today.

And it's really going to be the responsibility of the investor to understand all of the different avenues that they can take to manage risk and enhance return from these investments over the course of the years to come. So as always, Jared, it was an absolute pleasure. And with that, I think we'll bring it to a close.

Thank you for joining us today on J.P. Morgan's Center for Investment Excellence. If you found our insights useful, you can find more episodes anywhere you listen to podcasts and on our website. Thank you. Recorded on June 21, 2021.

[MUSIC PLAYING]

For institutional, wholesale professional clients and qualified investors only. Not for retail use or distribution. Not for retail distribution. This communication has been prepared exclusively for institutional, wholesale, professional clients and qualified investors only, as defined by local laws and regulations. The views contained herein are not to be taken as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment in any jurisdiction, nor is it a commitment from J.P. Morgan Asset Management or any of its subsidiaries to participate in any of the transactions mentioned herein.

Any forecasts, figures, opinions, or investment techniques and strategies set out are for information purposes only, based on certain assumptions and current market conditions and are subject to change without prior notice. All information presented herein is considered to be accurate at the time of production. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products. In addition, users should make an independent assessment of the legal, regulatory, tax, credit and accounting implications and determine together with their own professional advisors if any investment mentioned herein is believed to be suitable to their personal goals. Investors should ensure that they obtain all available relevant information before making any investment.

It should be noted that investment involves risks. The value of investments and the income from the may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions, and taxation agreements, and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Both past performance and yields are not reliable indicators of current and future results. J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the brand for the Asset Management business of JPMorgan Chase and Company and its affiliates worldwide.

To the extent permitted by applicable law, we may record telephone calls and monitor electronic communications to comply with our legal and regulatory obligations and internal policies. Personal data will be collected, stored, and processed by J.P. Morgan Asset Management in accordance with our privacy policies at http://an.JPMorgan.com/global/privacy. This communication is issued by the following entities in the United States by J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc. or J.P. Morgan Alternative Asset Management Inc. both regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission.

In Latin America, for intended recipients' use only, by local J.P. Morgan entities, as the case may be; in Canada, for institutional clients' use only, by JPMorgan Asset Management (Canada) Inc., which is a registered Portfolio Manager and Exempt Market Dealer in all Canadian provinces and territories except the Yukon and is also registered as an Investment Fund Manager in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec, and Newfoundland, and Labrador. In the United Kingdom, by JPMorgan Asset Management (UK) Limited, which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority; in other European jurisdictions by JPMorgan Asset Management (Europe) S.a r.l. In Asia-Pacific, ("APAC"), by the following issuing entities and in the respective jurisdictions in which they are primarily regulated: JPMorgan Asset Management (Asia Pacific) Limited, or JPMorgan Fund, (Asia) Limited, or JPMorgan Asset Management Real Assets (Asia) Limited, each of which is regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong; JPMorgan Asset Management (Singapore) Limited, (Company Reg. No. 197601586K), which this advertisement or publication has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore; JPMorgan Asset Management (Taiwan) Limited; JPMorgan Asset Management (Japan) Limited, which is a member of the Investment Trusts Association, Japan, the Japan Investment Advisors Association, Type II Financial Instruments Firms Association and the Japan Securities Dealers Association and is regulated by the Financial Services Agency, (registration number, "Kanto Local Finance Bureau (Financial Instruments Firm) No. 330"); in Australia, to wholesale clients only as defined in Section 761A and 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Commonwealth), by JPMorgan Asset Management, (Australia) Limited, (ABN 55143832080) (AFSL 376919).

Copyright 2020 JPMorgan Chase & Company. All rights reserved.

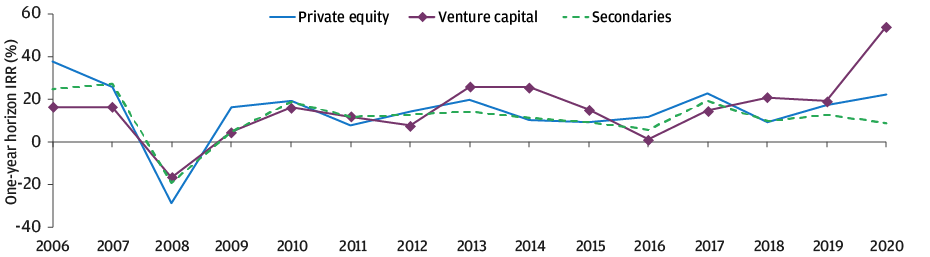

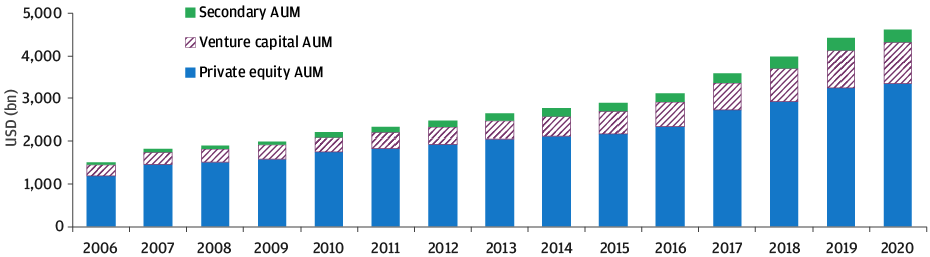

The role of private equity in institutional portfolios is clear: to deliver higher long-term returns than just about any other asset class. On this count, it has succeeded to a remarkable degree, providing investors with strong performance that has been more consistent and less volatile than they might have expected from strategies that make use of leverage and speculative growth assets. Manager skill has surely played an important role, but we should also recognize that multiple positive tailwinds have contributed to both the level and consistency of recent performance across the private equity sector (Exhibits 1A and 1B). A key question for investors today is how they should position their private equity portfolios for the next decade, given that some of these tailwinds may soon turn into headwinds.

Supportive market conditions, including falling interest rates, have contributed to strong fund performance in recent years; assets under management have also climbed

EXHIBIT 1A: Annual pooled internal rates of return (IRRs) for the private equity industry by fund type

Source: Burgiss Private iQ. Private equity consists of buyout and expansion capital, venture capital and secondary funds of funds; data as of December 31, 2020. Data represents pooled annual IRR at the end of each calendar year.

EXHIBIT 1B: AUM growth in the private equity industry by calendar year

Source: PitchBook; data as of June 30, 2020.

Private equity investors will generally point to a few key sources of value creation by managers. First is the application of organizational and operational efficiencies to improve the earnings of the underlying businesses prior to exit. Second is the ability to access cash flow for the paydown of debt or the return of capital to investors in the form of dividends – driven to some extent by the use of leverage. And third is the ability to realize higher multiples upon exit, although this result may be attributable as much to rising public market valuations as to manager skill in negotiating and executing sales.

Investors should take care not to confuse genuine skill with performance derived from a favorable market environment. Put differently, how much have external factors – including low and declining interest rates, exceptional levels of market liquidity, easy access to inexpensive leverage and rising public market valuations – given weaker managers undeserved support? The answer to this question matters, because should the markets shift and these external tailwinds become headwinds, we would expect to see both lower average returns across the sector and less consistency of performance across individual managers.

Time horizons and market cycles

Investors in private equity view the extended time horizon and limited liquidity as risks that must be borne in exchange for potentially high returns; managers of private equity view the same features as essential in giving them the flexibility to add value. Both are correct. Perhaps less well appreciated is that the investment horizon for a private equity investor will extend across market cycles, and the returns may be driven not only by decisions made within a fund but also by market forces outside it. Private Equity commitments made today may be invested and harvested in a future market environment that looks very different; managers that prospered in a time of abundant liquidity and rising valuations may face challenges in the years ahead (Exhibit 2).

As the probability of a market inflection point rises, private equity funds may be affected by changes in inflation, interest rates and equity market valuations

EXHIBIT 2: External factors influencing private equity performance

Because private equity investors are effectively locking in exposure to market environments that have not yet emerged, they need to anticipate the impact of changing conditions and the types of strategies that will continue to do well. The shifts described above may challenge funds with larger individual investments dependent on high leverage at inception and public markets upon exit. Conversely, smaller funds that invest in small and mid-size opportunities – with a greater focus on operational improvements and less reliance on leverage – should perform better.

Size, scope and scale in private equity funds

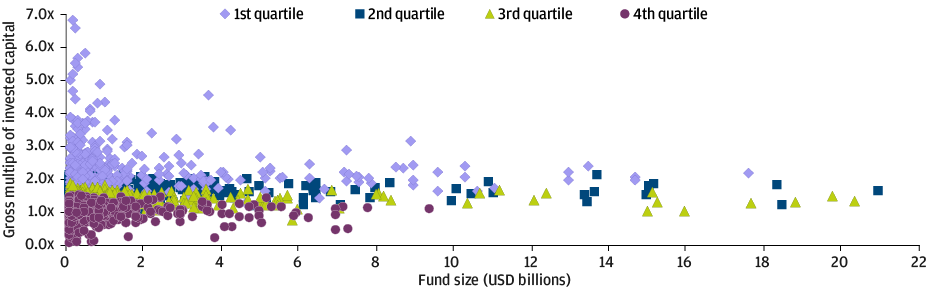

Surveying the population of private companies in the U.S., the vast majority (approximately 90%) fall into the small and lower mid-market space, where revenues range from $10 million to $100 million annually (Exhibit 3A). Mid-market companies represent an additional 5%–7% of the total, and larger firms with revenues greater than $300 million constitute the small remainder. It stands to reason that the opportunity set is deeper and richer for managers investing in smaller companies. The evidence supports this idea, as the population of top-quartile performers is heavily skewed toward smaller-scale opportunities and fund sizes (Exhibit 3B).

The number of companies in the small to lower mid-market range provide a deep pool of opportunities for private equity managers seeking to deliver outsize returns

EXHIBIT 3A: Total U.S. private companies, grouped by market size, revenue range and number

Source: FactSet; data as of May 30, 2021.

EXHIBIT 3B: Private equity industry performance dispersion by fund vintage year and size

Source: PitchBook; data as of May 30, 2021. Fund performance is as of December 31 2020 (or latest available date).

This suggests that a private equity strategy built around managers focused on small and mid-size opportunities can provide superior diversification and better potential performance. These types of investments may rely less on leverage and financial engineering, and more on bottom-up operational value creation, making them far more resilient to a changing external environment. Conversely, larger, more heavily leveraged investments will be more sensitive to public market multiple compression and will offer less attractive opportunities to exit if market sentiment turns negative.

Focusing on smaller managers involves risks, of course. Most notably, as Exhibit 3B shows, the small-fund space comprises a larger percentage of bottom-quartile managers to be avoided. Furthermore, the ability to adequately assess a vast pool of small managers requires internal expertise and resources that few investors possess. The response to these challenges, however, should not be to limit investments to a narrow group of large private equity firms; such an approach would preclude investing in many top-ranked small fund managers – and the returns and asset diversification that they can provide.

The role of external skill

A solution is available: accessing expertise in the form of a dedicated private equity fund manager that has the resources to deliver the advantages of smaller funds at a scalable size, while avoiding the downsides. A well-resourced external fund manager will:

- Apply expertise and experience – as well as valuable internal data – to adequately assess a large opportunity set of smaller funds and make relevant comparisons across managers.

- Deploy reputational leverage to gain access to top managers and to negotiate competitive fees, improving long-term performance.

- Deliver scaled investments far more quickly than an individual investor could prudently achieve with direct allocations.

- Use strong relationships with general partners to generate co-investments while selectively accessing the secondary market to enhance the underlying fund return, reduce blended manager expenses and shorten the “J curve.”

The enormous success of private equity investing should not distract investors from the reality that factors beyond manager skill have been key components of past performance. But markets are shifting, and the coming environment will offer some challenges. Larger and more highly leveraged strategies will likely face the strongest headwinds, while smaller strategies focused on bottom-up operational improvements in earnings and cash flow should continue to flourish. Well-resourced private equity managers are needed – managers capable of navigating the broad opportunity set, maintaining strong relationships with investors and general partners, and filtering out those strategies that have simply benefited from external market forces.