A new era for alpha generation in local emerging markets?

07/02/2020

Sirushe Hewazy

The global savings glut has been driving asset price valuations for the last decade or so. However, a break from savings to investment-led growth could challenge prevalent current account surpluses and likely change global flow dynamics. Emerging markets with high democratic standards and strong institutions will be better positioned to cope with this new world, where macro policy and ESG considerations are likely to play a bigger role than in the savings glut era.

Stanley Fischer, former Fed member and Israel central bank governor, gave a speech in July of 2017 titled ‘The Low Level of Global Real Interest Rates’. In that speech, away from the more obvious and traditional factors driving domestic interest rate levels, he focused on one factor that had been driving interest rates globally lower, the ‘global savings glut’ that Ben Bernanke had begun frequently alluding to years before.

Since the Great Financial Crisis (GFC), China has remained in full export growth mode to become the world’s manufacturing hub (‘Made in China 2025’). This model was aided by their strategy of keeping the RMB weak relative to the USD and other import countries’ currencies. The other major blocs like Japan and Europe however, embarked on their own easy monetary policies to keep their currencies from appreciating. So with all three blocs countering USD strength and maintaining current account surpluses, rather than allow for currency exchange rate adjustments leading to a more balanced relationship and increasing demand for US exports, those excess savings flowed into US financial assets instead. Treasuries, corporate investment grade paper and equities have been great beneficiaries of this dynamic.

European policy post European financial crisis of 2008 was to boost growth through external demand by adjusting monetary policy to weaken the Euro. The model was again a reluctance to go through the adjustment of transforming to a domestic consumption led model and instead to keep the export led model, cutting rates to negative territory as surpluses built up.

As global growth rebounded, and excess savings built up in the major export blocs, the flow into US financial assets built up pressure on the USD to strengthen, further putting pressure on US exports. However, as a relatively closed economy, the USD strength that transpires globally from real to financial asset world, eventually leads to tightness in credit markets and increases volatility. We have been used to these cycles now more frequently since the GFC.

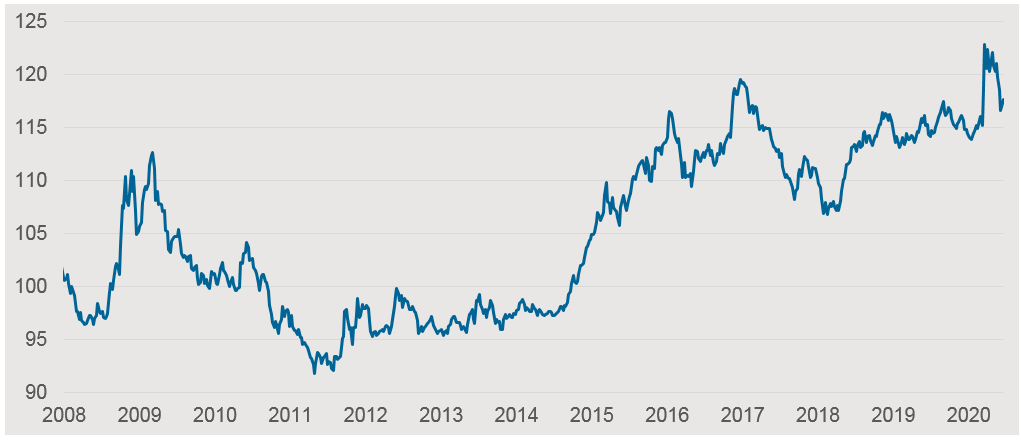

US Dollar under pressure to strengthen

Source: J.P.Morgan Asset Management, Bloomberg, As of 25.06.2020. J.P. Morgan US CPI-Based Real Broad Effective Exhange Rate

The one time we saw some sustained USD weakness since the GFC was 2016-2018 after we got China credit expansion through stimulus, leading to a sharp and significant boost in China excess liquidity. The effects were subsequently dampened with tightening of capital controls.

As Asia and Europe maintained their export led growth models, global savings continued to climb as savings exceeded investments and these blocs maintained their external surpluses. Added to that has been their fiscal austere/prudence stance. The economic shocks we have experienced through the global pandemic, has led to corporates (that can) and households to enter into savings mode, which has built up the global savings glut. There was no other choice but for governments to counter this with fiscal easing, and do away with austerity. This global savings glut can’t find enough risk free assets domestically and has continued to find its way into US financial assets.

What has the global savings glut led to?

As the savings glut has risen, and savings has exceeded investments, the drop in global monetary policy rates and the richness in domestic risk-free assets has led to an overflow of capital that has been exported to the US. This has had a profound effect on US financial assets starting with the risk free rate and across the credit curve. It has also led to the conundrum that Ben Bernanke has often talked about, that in a world so globally integrated financially, US monetary policy is now being significantly influenced by policies abroad rather than being the driver of world policy.

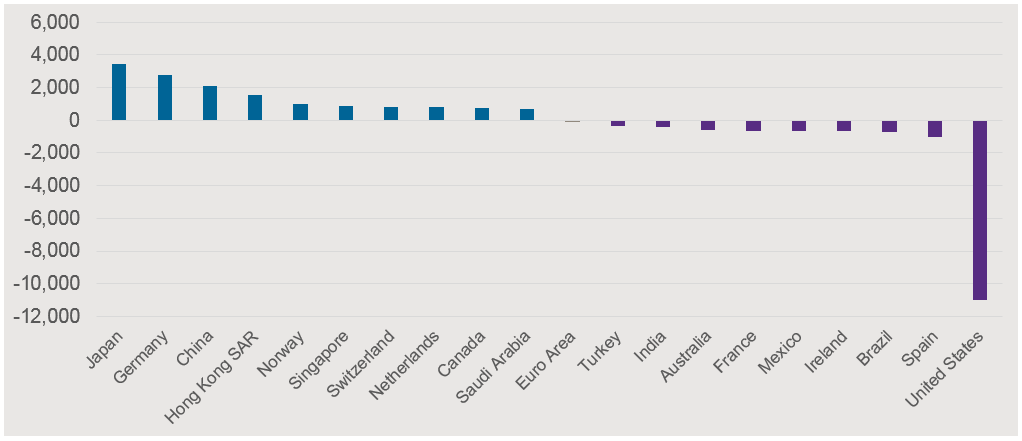

Excess savings glut flowing into USD assets

Source: J.P.Morgan Asset Management, International Monetary Fund (IMF), As of December 2019. Net International Investment Position 2019 (USD mio)

This whole dynamic has led to the drop in R-Star (r*)[1] that Mark Carney spoke about in August of 2019 at Jackson Hole (along the same lines of Ben Bernanke), where domestic monetary policy settings is being impacted by the dynamic of the global savings glut. The rate impulse has been declining, so that monetary rates are gravitating towards a neutral level merely to catch up with the savings glut dynamic and not as a price stability tool as effectively as in the past. The reflexivity of this however has been reinforcing and leading to disinflationary pressures as well. All in all, we are at zero bound/NIRP rates due to the effects of the savings glut globally that has come about because of currency policies from Asia and Europe.

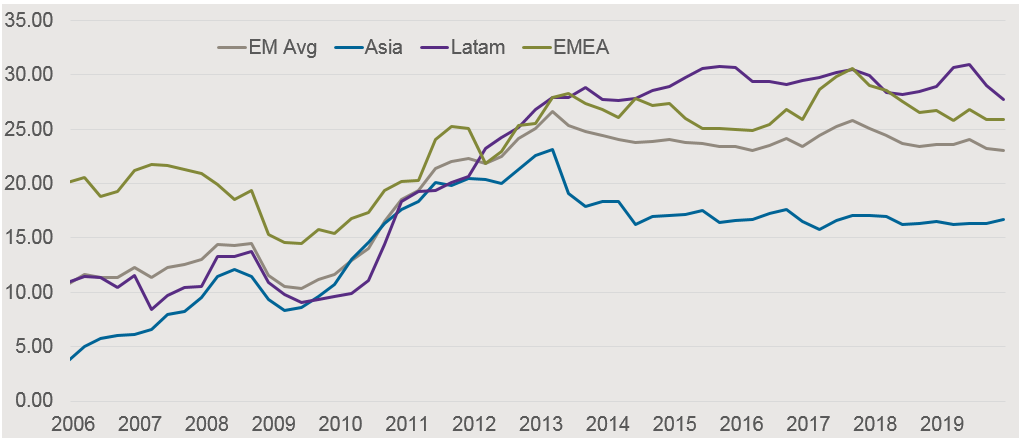

This overflow of savings glut has also found its way to riskier assets, especially in times of global ‘stability’, and emerging markets assets have been one of the beneficiaries of these flows, as the yield differentials have compared favorably. It is, however, this flow dynamic creating bigger foreign holdings of domestic debt (see chart below) that has led to more volatility in the flows and ultimately higher currency volatility.

Foreign Participation in Local Currency Government Bond Markets (% of outstanding)

Source: J.P.Morgan Asset Management, Institute of International Finance (IIF), As of December 2019

Breaking the flow dynamic?

The global savings glut has been driving the world of asset price valuations for the last decade or so, and this dynamic will likely dictate where we go over the next decade. If economic blocks who have been exporters of excess savings outwards start to look inwards, could we see a buildup of risks to this dynamic, such as steps towards fiscal union in the EU and a break with fiscal austerity? Could this risk the flow dynamics down the risk curves and into emerging markets? And will those countries with larger foreign holdings of its debt come under greater pressure to move debt into domestic hands?

This potential dynamic may open up the world down the line to reverse the recent disinflationary/deflationary pressures by focusing on investment over savings and in this ensuing new era could see long end yields in the Emerging Markets space start to rise as they compete for a more limited pool of flows with the deglobalisation of capital.

Ultimately, differentiation among Emerging Markets will, in all likelihood, continue to become more apparent. Over time, investment booms in large economic blocs (like the Eurozone) would help fuel growth and growth expectations, and with it bring capital flows supporting domestic asset prices and respective currencies. The recent past was led by growth coupled with savings. However, if we were to see investment led growth and vice-versa a drop in the current account surplus models of recent times, the price of money would likely start to rise and yield curves globally steepen over time.

At a crossroads

Today, emerging markets are standing at a crossroads. Those with strong policy frameworks, credibility in central banks and government institutions, and with high democratic standards will probably become more domestically funded and subject to less volatility, supporting local currencies and asset prices. Those that go the other way, will remain challenged and vulnerable during times of global stress. They will be competing for foreign capital inflows to fund their deficits and at the same time battling against domestic capital flight looking for better investment proposals abroad. To some extent, we can already observe these divergent trends today. Looking forward, if we are to head into a new era of investment led growth, we can expect to see an even bigger differentiation within the emerging markets space. Local currencies and yield curves will see the first signs of this trend, presenting a new era for alpha generation in local market, where macro policy and ESG considerations will play a much bigger role than in the world of the savings glut.

[1] An explanation of R-star is discussed in a blog written in 2017 by Jason Davis – click here