Diversified core-plus transportation: A track record of strength during economic disruption

In brief:

- Disruption to the global economy from COVID-19 has affected transportation assets in widely varying ways. New disruptions from virus-related lockdowns, rising inflation and geopolitical conflicts could extend these trends.

- The maritime shipping industry is benefiting from a tight current supply of ships, with many stuck in long queues in ports, while future supply looks constrained.

- Among transport subsectors, aviation has been slower to recover, and its outlook is more negatively impacted by uncertainty surrounding travel restrictions and border controls.

- The performance dispersion between these subsectors highlights the case for a diversified approach to investing in transportation, which may continue to provide investors with the potential for stable income derived from long-term leases.

Disruption from the COVID-19 pandemic has stretched global supply chains and logistics networks to their limits, while related travel restrictions have hindered air passenger mobility. Yet the impact across transportation assets has ranged from positive to negative, depending on the subsector. For example, while maritime shipping is benefiting from a favorable supply-demand outlook, the aviation industry faces continued headwinds from uncertainty related to the pandemic.

The performance dispersion between these subsectors since the onset of the pandemic strengthens the case for a diversified approach to portfolio construction when investing in transportation assets. Core transportation assets remain critical to end users’ logistics operations and are essential connectors among industries and economies. These assets operate on “take-or-pay” leases1 supported by the strong credit of large corporations; this long-term contracted revenue supports stable, consistent yield, even during periods of volatility.

To be sure, continuing global challenges, including geopolitical conflict, ongoing intermittent pandemic lockdowns in major Chinese export hubs and the possibility of environmental regulatory action, could impact individual transportation subsectors to varying degrees.

Shipping: Perfect storm of robust global demand and virus containment measures has created supply chain pressure

Since the start of the pandemic, governments have injected a historic USD 17.0 trillion into the global economy through measures such as infrastructure spending and direct payments to individuals.2 The infrastructure stimulus during 2020—2021 drove up demand for many raw materials.3 Much of the stimulus-powered consumer spending was directed toward goods rather than services.

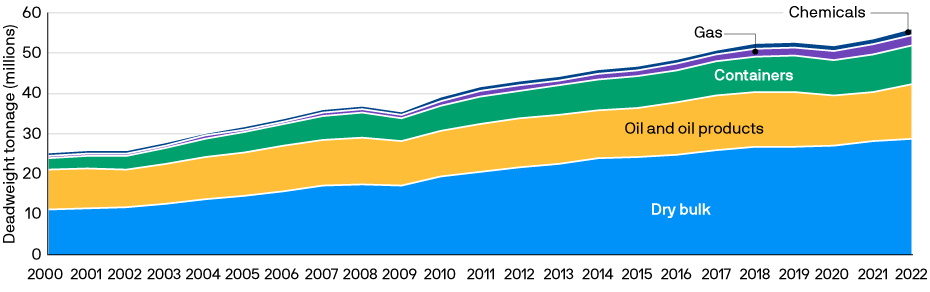

Greater demand for raw materials and finished goods boosted the maritime industry, which carries over 90% of global trade.4 Trade volumes returned to pre-COVID-19 levels by mid-2021, and total seaborne trade volumes ended last year up 3.7% year-over-year (Exhibit 1). Container trade volumes were up 5.2%, and dry bulk up 2.4%, above pre-pandemic levels at the end of 2021.5

Seaborne volumes recovered to pre-pandemic levels by mid-2021 and ended the year on a new high

Exhibit 1: World seaborne trade volumes 2000–2021

Source: Shipping Intelligence Network, Clarksons,.Data as of March 1, 2022.

While demand has remained strong, several factors are contributing to supply bottlenecks. COVID-19 safety protocols and frequent intermittent shutdowns due to localized outbreaks have slowed operations at manufacturing and export hubs in Asia, as well as at import gateways in the United States and Europe. Shortages of truckers, longshoremen and warehousing staff are compounding the issue.

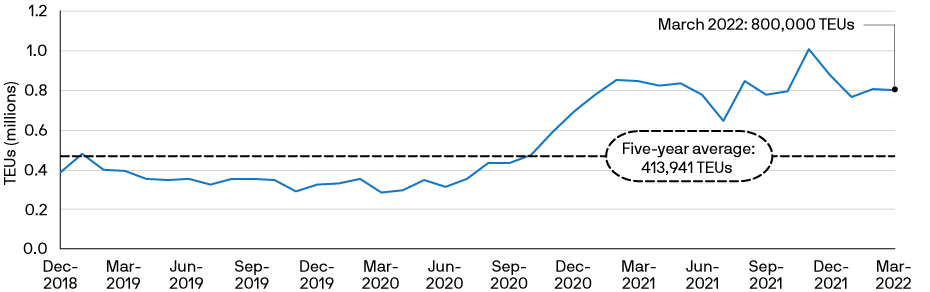

As a result, large numbers of ships sit outside ports while they wait to discharge cargo. For example, statistics from the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach, the largest port in the United States, show that wait times for container ships during the second half of 2021 averaged over eight days, up from limited or no waiting time previously, according to data from the Marine Exchange of Southern California. Although port congestion has eased slightly in recent months, as of March 2022, container backlogs remain nearly double the five-year average (Exhibit 2). Disruption continues to drive backlogs at other major ports around the world, where similar levels of congestion remain.

Backlogs at major ports are reducing the supply of ships

Exhibit 2: Container ships waiting in the Port of Los Angeles/Long Beach (TEUs)

Source: Shipping Intelligence Network, Clarksons. Data as of March 1, 2022. TEU = 20-foot equivalent unit, a measure for container ship of cargo capacity.

The extended queue times artificially reduce the supply of ships and create shortages of critically needed assets. Ships waiting to discharge cargo are not available to move other goods and materials that they would otherwise be transporting. The shortage of ships has also driven lease rates to records highs, significantly benefiting owners of these assets.

Ample opportunity for shipping with minimal risk of oversupply

Over the long term, more ships will be needed to keep pace with likely growing consumer demand, but shipyard manufacturing capacity is constrained. Consolidation has reduced the number of active large shipyards to only 111, compared to 320 at the peak in 2008.6 Manufacturing capacity remains well booked due to the strong demand and long lead times. The construction period for ships typically lasts 12 to 24 months, which means the earliest available delivery window for new ships is currently in 2025.9

In addition, demand for new types of ships needed for the ongoing energy transition, such as wind turbine installation vessels (WTIVs), wind farm service and operation vessels (SOVs), and next-generation liquefied natural gas carriers (LNGCs), is set to put further pressure on shipyards and limit the oncoming supply of traditional shipping assets. For example, the U.S. Infrastructure bill signed by President Biden in in November 2021 calls for the deployment of 30 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, creating significant demand for assets to install and service offshore wind farms.7 Demand for transitional fuels such as LNG is also rising. Some estimates suggest that the current LNGC fleet of approximately 600 vessels may need to increase by 350 to meet growing LNG demand.8

At the same time, asset values are increasing, while Post-Global Financial Crisis regulation has constrained the ability of traditional banks to provide capital to the sector, minimizing speculative ordering and creating a need for more equity capital. Additionally, a "flight to quality" has focused lending activity on a small group of strong market players.

Overall, restrained capacity additions and limited oversupply risk are creating a more stable shipping subsector than historically witnessed. Investors benefit from the enhanced support provided to “take-or-pay” leases by end users with stronger credit profiles.

Aviation: Travel restrictions ground aircraft and curb profits

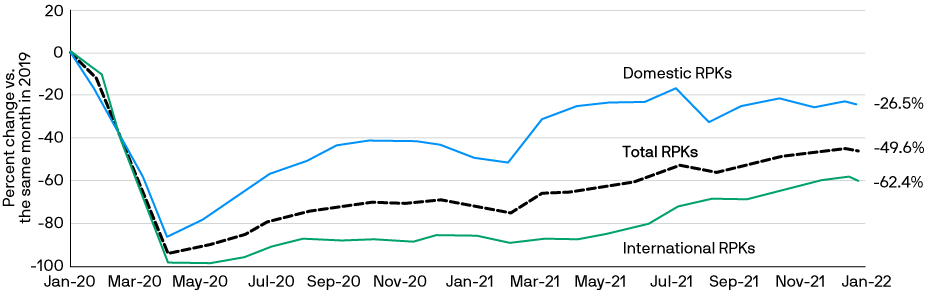

Border closures and travel restrictions have caused one of the worst two-year periods on record for airlines. In 2020, global passenger volumes were down approximately 60% compared to 2019.10 Domestic U.S. travel recovered slightly in 2021, with passenger volumes recovering to 26% below pre-pandemic levels by year-end, but border restrictions significantly hampered international travel. In 2021, overall global passenger volumes remained down approximately 50% on 2019 levels (Exhibit 3).11

Airline travel has recovered from 2020 lows, but the outlook remains uncertain

Exhibit 3: Global revenue passenger kilometers (RPKs) for international and domestic U.S. flights

Source: “Air Passenger Market Analysis—Strong demand recovery in January but impacted by Omicron,” IATA, January 2022.

Total net industry losses during 2020 and 2021 reached nearly USD 190 billion.12 As a result, over 70 airlines have declared bankruptcy as of March 2022. Many lessors have experienced lease payment defaults or deferrals, leaving investors without a primary source of return.

Uncertainty currently clouds the aviation recovery timeline. Current forecasts suggest domestic travel will reach approximately 93% of pre-pandemic levels in 2022. However, the outlook for international travel remains depressed: Estimates suggest a recovery to only 44% of pre-pandemic levels in 2022.13 The aviation subsector continues to grapple with concerns created by new variants of the coronavirus, dynamic border controls and questions about the future of in-person business, pushing the recovery timeline further into the future.

Overall strong fundamentals support the case for investing in a diversified transportation portfolio

While virus response and travel restrictions have caused major losses in the aviation sector, port congestion and supply chain disruption have highlighted the critical role of shipping in global trade. These widely differing situations within the transportation industry during the past two years strengthen the case for a diversified portfolio of assets with long-term contractual cash flows backed by strong counterparty credit.

We don’t know exactly when new coronavirus variants will emerge, how long supply chain disruption will linger, how geopolitical developments will be resolved, or if the airline industry will return to its pre-pandemic peak. However, we continue to believe a diversified approach to transportation investing has the potential to offer resilience and help investors mitigate portfolio volatility.

1 Under “take-or-pay” lease structures, lessees have no unilateral ability to modify or cancel the terms of lease, unless the lessee has entered a court-administered reorganization (bankruptcy), meaning that lessees are legally required to make payments regardless of underlying business plan changes or economic environment changes.

2 Shipping Intelligence Network, Briefings, Clarksons, https://sin.clarksons.net/, February 3, 2022.

3 Shipping Intelligence Network, Time Series, Clarksons, https://sin.clarksons.net/.

4 OECD, https://www.oecd.org/ocean/topics/ocean-shipping/, Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

5 Shipping Intelligence Network, Time Series, Clarksons, https://sin.clarksons.net/.

6 Shipping Intelligence Network, Shipyard Orderbook Monitor, Clarksons, https://www.sin.clarksons.net/.

7 FACT SHEET: Biden-Harris Administration Races to Deploy Clean Energy that Creates Jobs and Lowers Costs, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/01/12/fact-sheet-biden-harris-administration-races-to-deploy-clean-energy-that-creates-jobs-and-lowers-costs/.

8 TradeWinds, "LNG industry hears horror story the market could run out of ships", Lucy Hine, https://www.tradewindsnews.com/gas/lng-industry-hears-horror-story-the-market-could-run-out-of-ships/2-1-1113863.

9 “Shipping Market Review—November 2020,” Christopher Rex, Danish Ship Finance, https://www.shipfinance.dk/media/2054/shipping-market-review-november-2020.pdf, November 2020.

10 “Airline Industry Statistics Confirm 2020 Was Worst Year on Record,” IATA, https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/pr/2021-08-03-01/, August 3, 2021.

11 “Losses Reduce but Challenges Continue—Cumulative $201 Billion Losses for 2020—2022,” IATA, https://www.iata.org/en/pressroom/2021-releases/2021-10-04-01/, October 4, 2021.

12 “Airline Industry Outlook,” IATA, https://www.iata.org/en/iata-repository/publications/economic-reports/december-passenger-traffic-likely-to-be-resilient-despite-omicron/, October 4, 2021.