Markets are confident that the Fed’s more balanced view will not derail its fight against inflation.

In brief

- Central banks around the world have hiked more than 100 times this year.

- The U.S., euro area and the UK, all recently announced themselves to be on wait-and-see mode.

- The BoJ further adjusted its YCC policy, but maintained its negative interest rate policy.

- In the past five hiking cycles, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields typically peaked before the peak in the fed funds rate. Between the last rate hike and first rate cut, yields also fell 107 basis points.

What markets have been waiting for?

After a historically aggressive year of monetary tightening in 2022, developed market (DM) central banks still delivered nearly 50 hikes in total so far in 2023. As key DM central banks recently start to put rates on hold, the end is finally in sight. Financial conditions are becoming restrictive to cool business activities. However, there are several factors that may push central banks to still tighten further, such as tight labor markets, oil supply risks and fiscal spending in response to upcoming elections. In this piece, we will tour around key central bank decisions to gauge whether we are truly at the end.

On hold, at least for now?

The 3 major developed markets—U.S., euro area and the UK all recently adopted a patient approach, preferring to wait and see how the economic data develops given macro uncertainties.

Markets reacted positively when the Federal Reserve (Fed) kept policy rates at 5.25%-5.50%, a 22-year high, with an overall more balanced policy statement. At the time of writing, markets are pricing in a 90% probability that the Fed will continue to hold in December as well, and the 5-year-5-year breakeven rates are holding steady at 2.5%, indicating markets are confident that the Fed’s more balanced view will not derail its fight against inflation. Indeed, the October nonfarm payrolls showed signs of a cooling labor market, and the run-up in 10-year U.S. Treasury yields since September have likely done part of the Fed’s job (economists estimate the effect is equivalent to three 25bps rate hikes). However, hawks would point to the 3Q23 GDP print as a sign that monetary policy is not restrictive enough, or the fact that monetary policy transmission is likely not as lagged as history suggests, given higher transparency from the Fed, not to mention the sticky components of “super core inflation”. On balance, although we don’t think another hike would be necessary, whether the Fed will still hike once more for security remains a close call.

Over in Europe, the certainty of a cycle end seems higher. Both the European Central Bank (ECB) and Bank of England (BoE) held rates steady. There, the growth picture is significantly weaker than the U.S., to the extent that gives central banks more confidence in disinflation momentum, but not too weak to push the economy off the cliff. This “not-too-hot, not-too-cold” growth backdrop is perhaps relieving for central banks. However, they both highlighted the need for rates to be “sufficiently restrictive for sufficiently long”, likely causing growth to grind even slower as the tightening effects begin to bite.

Another step towards policy normalization

The Bank of Japan (BoJ), while maintaining negative interest rate policy during its recent meeting, announced a further increase in the flexibility around the way it conducts yield curve control (YCC) policy. The BoJ set a 1.0% upper limit as a reference, rather than a strict cap to the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield.

While the YCC policy adjustment can be interpreted as another step towards tightening, official commentary suggests that inflation is still considered more transitory and driven by supply side factors. Although the BoJ’s inflation forecasts were raised for 2023 and 2024, based on factors such as the rise in crude oil prices, as well as the waning effects of government subsidies on gasoline and electricity bill subsidies. The BoJ will therefore need to have more confidence that inflation is being driven by higher wage growth and demand factors before moving away from negative interest rate policy and abolishing YCC. It will also need to be mindful not to hike rates when the global economy is slowing down.

In addition to inflation dynamics, the BoJ will also want to maintain foreign exchange (FX) stability. Widening yield differentials relative to the U.S. has led to weakness in the Japanese yen (JPY) recently, with the USDJPY breaching 150—the JPY’s weakest point relative to the greenback since the early 1990s. Given the skepticism around the permanence of inflation, the loosening of YCC has done little to soothe the recent depreciation of the JPY. To reverse the course of weakness, any indications around a change in short-term rates and exit from NIRP could drive yen appreciation. While excessive JPY weakness may exacerbate imported inflation, which may then force the BoJ’s hand to tighten conditions, the management of FX volatility is mainly the Ministry of Finance’s prerogative.

Still moving up down under

On the other hand, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) continues to be in tightening mode as it lagged other DM central banks in the tightening cycle. Despite a cooling labor market, a stronger-than-expected third quarter core consumer price index and continued strength in consumer spending forced the RBA to re-engage its hiking cycle after holding rates steady for four straight meetings. This makes it the 13th rate hike for the RBA in the current hiking cycle, lifting cash rates to a 12-year high of 4.35%.

Time to go long duration?

Equity markets have rallied recently as 1) markets are increasingly expecting major central banks to be finished with rate hikes and 2) third quarter U.S. earnings have showcased resiliency in profit margins contributing to upside surprises to earnings.

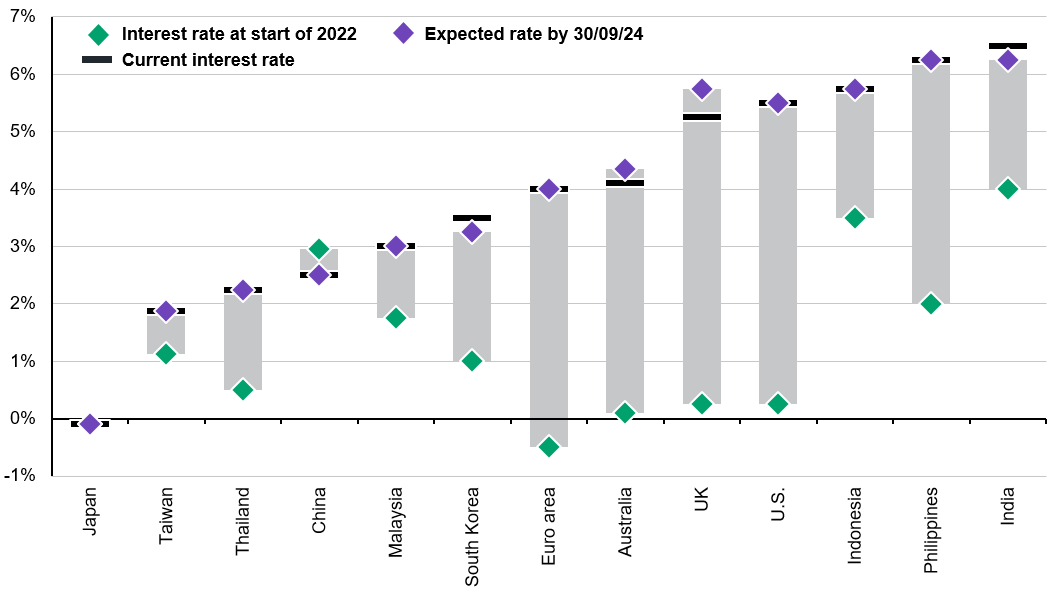

In the past five hiking cycles, 10-year U.S. Treasury yields typically peaked before the peak in fed funds rate. Between the last rate hike and first rate cut, yields also fell 107 basis points. With disinflation momentum and tight financial conditions, most DM central banks are near, if not already at the end of their hiking cycle (Exhibit 1), which would limit the upside for yields.

Given this outlook, we still see gradually lengthening duration to be the right approach going into 2024. Falling yields could also benefit long duration assets, such as growth stocks and gold.

Exhibit 1: Expected change in central bank policy rates