On August 7th, with little fanfare, the IRS announced that, as part of its phased implementation of the OBBBA, it would not be adjusting W2 or 1099 forms for the current calendar year but would provide guidance and new forms, in due course, for calendar 2026.

This seemingly innocuous statement confirms that we will see in an even larger crop of personal income tax refunds early in 2026 than was anticipated when the OBBBA was passed. These higher income tax refunds should work much like a new round of stimulus checks, adding to consumer demand and inflation pressures early next year.

After Jay Powell’s Jackson Hole speech, it looks very likely that the Fed will resume rate cuts at its September meeting. However, this prospective economic sugar rush from refunds is a good reason for the Fed to delay. Moreover, these refunds are sugar, not protein, and when their effects fade, it is quite possible that Washington will provide yet another round of stimulus to boost demand ahead of the mid-term elections. For investors, this underscores the limited potential for a sustained decline in long-term interest rates and the need to add alternative sources of diversification to portfolios.

Measuring the Refund Surge

As OBBBA was winding its way through Congress, economists at the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) were furiously trying to estimate its budgetary impacts. One useful document from this effort was released on July 1st, showing the revenue effects of the legislation relative to current policy, that is to say, relative to a simple extension of the 2017 tax cuts.

One particularly important issue, that we have highlighted before, is that a large group of tax breaks, many of which the President had campaigned on, were set to take effect, retroactively, on January 1st, 2025 and expire on December 31st, 2028. This design is astute from a political perspective for two reasons.

First, by proposing to finance four years of tax cuts with ten years of spending cuts, the government provides the illusion of fiscal restraint without much of the associated pain. When the tax cuts are set to expire, politicians will, of course, call loudly for their extension and denounce anyone opposing that effort as wanting to raise taxes on the American people. And so a temporary tax cut becomes a permanent one.

Second, by backdating the tax cuts to the start of 2025, the legislation ensured that taxpayers would see a bumper crop of refunds in early 2026, since income tax withholding schedules wouldn’t have been changed before the passage of the legislation. Moreover, with the IRS’s August 7th announcement, it is clear that they won’t be changed at all in 2025, meaning that far too much money will have been withheld from taxpayers and refunds will surge in early 2026.

But by how much?

Apart from extending the 2017 tax cuts, there are seven major individual income tax provisions in OBBBA that took effect, retroactively, on January 1st of this year. These are: no income tax on tips, overtime or auto loan interest and a new bonus deduction for people over age 65, (all of which expire at the end of 2028), an increase in allowable SALT deductions (which expires at the end of 2030) and permanent increases in the standard deduction and the child tax credit.

In early July, the JCT estimated that these provisions would cost $24 billion in fiscal 2025 (which ends in just over a month), $131 billion in fiscal 2026 and $116 billion in fiscal 2027. However, given that there is no change in withholding schedules, unless individual taxpayers take it upon themselves to adjust their own W4 forms, there is unlikely to be any meaningful revenue loss due to these provisions in either fiscal or calendar 2025. This means that taxpayers should be able to recoup the full value of these tax breaks in bigger income tax refunds (or lower annual payments) when they file their 2025 income taxes early next year.

Because of timing differences between tax years and calendar years and the fact that income tax withholding only directly impacts some of these breaks, it is very difficult to disentangle the revenue impacts for 2025 and 2026. However, the total cost of these provisions for fiscal 2027, at $116 billion, should be very close to the amount owed to taxpayers for calendar 2025, deflated by, say 8%, for the growth in income in between – so roughly $107 billion.

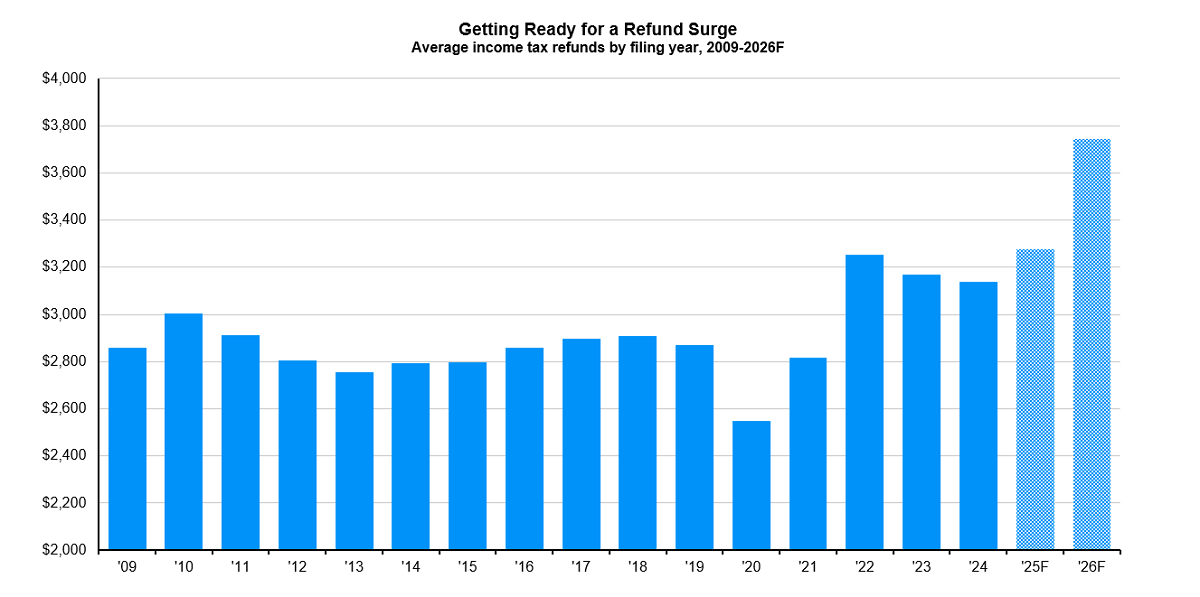

Based on data through mid-May, we estimate that the IRS will process 166 million individual income tax returns in the current calendar year, paying an average refund of $3,278 to 104 million taxpayers. If, for simplicity, we assume that two thirds of the retroactive individual income tax breaks in the OBBBA are paid out in the form of refunds and one third in the form of lower annual payments, then the number of refunds could climb to 110 million with an average payment of $3,743. (Estimates of the relative impact of these tax breaks on refunds versus annual payments is, of course, very speculative but this should make no difference to their combined economic impacts.)

The Economic Impact of the Refund Surge

Higher income tax refunds and lower annual payments should boost consumer spending in a similar way to pandemic stimulus checks. Still there is one important difference:

All of these tax breaks, with the exception of the child tax credit, are in the form of deductions rather than credits. This means that the higher your marginal tax rate, the greater is the value of the deduction. For 2025, the federal income tax rate for a married couple filing jointly, is 10% on taxable income up to $23,850, edging up to 12% from $23,850 to $96,950. But then it jumps to 22% from $96,950 to $206,700 and to 24% from $206,700 to $394,600. Adding in the standard deduction (which has now been raised to $31,500), these tax breaks will be worth far more to families earning over $130,000 per year than to those with earnings below this level.

The tax breaks do begin to phase out at $500,000 for the SALT deduction, $400,000 for the child tax credit, $300,000 for the tax break on tips and overtime, $200,000 for auto-loan interest and $150,000 for the senior bonus deduction. Nevertheless, these tax breaks will be much more valuable to upper-middle-income households than their lower middle-income and lower-income counterparts, with most of the benefits accruing to households between the 50th and 90th percentiles in income.

Richer households save more of their income than poorer households, with households between the 50th and 90th income percentiles saving approximately 16% of their disposable income in 2023. Consequently, extra consumer spending from every extra dollar in refunds in 2026 may be a little less than occurred with the pandemic stimulus checks, (which were the same dollar amount for lower and middle income households but phased out at higher incomes). This also means a little less demand for consumer basics and a little more for discretionary spending.

Looking at the overall economic impact, if we assume that 80% of these extra refunds are spent, this amounts to roughly 0.27% of GDP. If this money were spent evenly in the first six months of 2026, it could boost annualized real GDP growth by over 0.5% in the first quarter. If we add to this the impact of lower withholding that should finally kick in at the start of 2026, it could add 0.8% to real GDP growth in the first quarter. Moreover, it could even reach back to impact the holiday season this year. If consumers are confident that they will be getting bigger refund checks early in the new year, they may be willing to rack up more credit card debt in December, providing further near-term support to the economy.

However, as mentioned earlier, this is essentially sugar rather than protein. Last year, the IRS had paid out 56% of total income tax refunds by the end of March and over 80% by the middle of May, with over 90% of the money getting directly deposited into taxpayer accounts. If consumers generally use this money quickly, then by the third quarter of next year, consumer spending could slow again and, by the fourth quarter, it could slump.

The Possibility of Further Stimulus and the Fed’s Dilemma

Jay Powell’s Jackson Hole speech made no reference to the upcoming refund surge, but it is important as it could sustain both economic growth and above-trend inflation well into 2026. If he had mentioned it, he might have suggested that bumper tax refunds, just like tariffs, are simply a temporary issue and that inflation will fade once they have played out, justifying near-term Fed easing.

However, one problem with this logic is the assumption that the administration and Congress will be willing to see the economy slow in the second half of next year. Once the refunds season winds down, the economy will still have to contend with the drags from higher tariffs and lower immigration. It could well be that, faced with this possibility, Congress approves some further fiscal stimulus such as the “DOGE dividends” that were floated earlier this year or the more recently proposed “tariff rebate checks”.

Investment Implications

For investors, this is an important issue to consider. It now seems likely that the Fed, under intense pressure from the administration, will lower interest rates by 0.25% on September 17th. Such a move is unlikely to spur faster economic growth in the short run, setting the stage for another rate cut in October or in December or both. If this occurs, in the face of rising inflation and as a refund surge threatens to sustain that higher inflation, investors might doubt the Fed’s commitment to stable inflation, potentially leading to a steeper yield curve, a lower dollar and lower stock prices. For investors, this underscores the need to have a greater allocation to international assets denominated in foreign currencies and the importance of having alternative assets with lower correlations to U.S. stocks and bonds.