We began this year expecting to discuss the 2020 presidential election almost exclusively. However, the rise and spread of COVID-19 has derailed most of those conversations, rightly so, and has changed the backdrop of the 2020 election dramatically. Over the last several weeks, the economy has quickly plunged into recession, with economic activity coming to a halt to combat the spread of COVID-19, ending the record-long 11-year economic expansion. The race has narrowed, with former Vice President Joe Biden the presumptive Democratic nominee. The timetable for the contests and conventions in the run-up to Election Day has been upended. The procedures for conducting a national election must be amended for a social distancing environment, which likely still will persist in some form in November. Lastly, the next president of the United States will necessarily have a different policy agenda now given the events that have unfolded than he would have at the beginning of the year. While most of the national attention is focused on the virus, the results of the 2020 election will be very consequential for the recovery and rebound efforts ahead.

A two-man race

What was previously a very crowded field on the Democratic side has now been whittled down to one presumptive nominee, former Vice President Joe Biden. Biden performed poorly in the first three races of primary season, but staked his candidacy on South Carolina, which paid off when he won. Former South Bend Indiana Mayor Pete Buttigieg and Senator Amy Klobuchar then dropped out and endorsed Biden, consolidating the moderates. Momentum coalesced for Biden, who went on to win 10 of the 14 states on Super Tuesday (March 3), the biggest single-day contest of primary season. He scored key victories after that in Michigan and Florida, among several other states.

By mid-March, the delegate math became challenging for Sanders to find a path to victory, and he suspended his campaign on April 8th. However, despite endorsing Biden and affirming that Biden will be the party’s nominee, Sanders did say he would continue to try to gather delegates in order to exert more influence on the party’s platform at the Democratic National Convention, although in reality substantial policy debate will probably be limited.

Despite Biden’s swift consolidation of support to become the presumptive nominee, he has a long and challenging road ahead for the presidential election. This environment of social distancing, which is likely to persist in some form through the end of the year, makes it impossible for rallies or large political gatherings on the campaign trail. Biden will instead have to rely on media, television, and social media, much of which needs to be fueled by a large budget. In his prior campaigns for the Democratic Party’s nomination, Biden has struggled to mobilize a small-dollar donor fundraising machine, of the sort that has fueled Senator Sanders’ last two campaigns, and instead relied on in-person high dollar fundraisers. The current pandemic calls the feasibility of such a strategy into question.

Social distancing will also threaten voter turnout, which is critical for a Democratic presidential victory given that the presidency is determined by who wins at least 270 of the 538 Electoral College votes, not a simple majority of the popular vote. In the 2016 election, President Trump was elected with 306 Electoral College votes to 232 for Hillary Clinton, but actually lost the popular vote, polling 46.1% to 48.2% for Clinton. Ultimately, the three states that effectively determined the election in President Trump’s favor were Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. These races were all determined by a spread of less than 0.8% between the candidates. If the Democrats are able to swing these states by just under 2% cumulatively, keeping all else constant from 2016, they are likely to win the Electoral College. Therefore, on election night, these three states, along with the other 5 tightest races of 2016—New Hampshire, Florida, Minnesota, Nevada, and Maine— will likely determine the outcome.

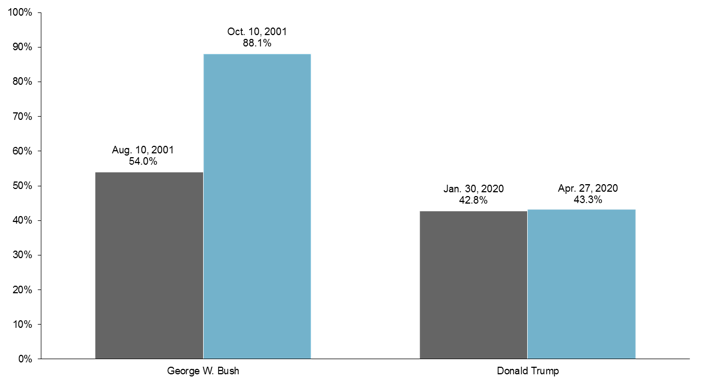

However, at the same time, the odds of President Trump being re-elected have changed in light of COVID-19. An incumbent president has won reelection 65% of the time since the Civil War. However, in all instances in which the incumbent lost, there was a recession or depression during their term. The impacts of COVID-19 have pushed the U.S. economy into recession. The labor market is facing an unemployment rate at its highest since the Great Depression. While this could greatly diminish the chances of a Trump victory, the critical swing factor will be the public perception of the president’s management of this crisis, particularly among his voter base. After all, George W. Bush’s approval ratings soared by over 30% after September 11th. Thus far the current president hasn’t seen a meaningful jump (Exhibit 1).

Exhibit 1: Approval ratings before and after national crises

Redrawing the path to Election Day

The spread of COVID-19 has not only upended the remaining primary season calendar, but will also change the way voters cast their ballots on Election Day. Florida, Arizona and Illinois were the last states to hold Democratic primaries on March 17th before state lockdowns began in earnest. Controversially, Wisconsin went ahead with its primary on April 7th, as the state Supreme Court ruled the governor could not postpone the primary over COVID-19 concerns. However, sixteen states and one territory have either postponed their primaries or switched to vote-by-mail with extended deadlines. The Democratic National Convention, at which the Democratic candidate is officially nominated to represent the party in the presidential election, has been pushed to August 17-20th from July 13-16th, a week before the Republican National Convention.

Not only has the path to Election Day been altered, but Election Day itself will look very different than any election the country has seen. Mail in voting could become much more pervasive, although expanding and changing voting measures is a hotly contested partisan issue. Not to mention, scaling up on different measures, such as mail in voting, requires immense preparation starting immediately.

We do have a model for what a pandemic election might look like, as South Koreans went to the polls on April 15th. While South Koreans could vote by mail, those without symptoms or sick family members could vote in person. Voting stations where disinfected, voters had to stand one meter apart at taped markers, they submitted to temperature checks, and they were given hand sanitizer and gloves. Again, to implement these procedures across the United States would require enormous preparation, planning and funding.

0903c02a828bc546