Will supply chain pressures persist?

An ongoing challenge from the COVID-19 pandemic has been the disruption of global supply chains, most notably a shortage in the supply of semiconductors. There is an expectation that these pressures will ease as COVID-19 is controlled and supply and demand imbalances fade. However, successive waves of COVID-19 cases delayed this process with implications for the economy and markets.

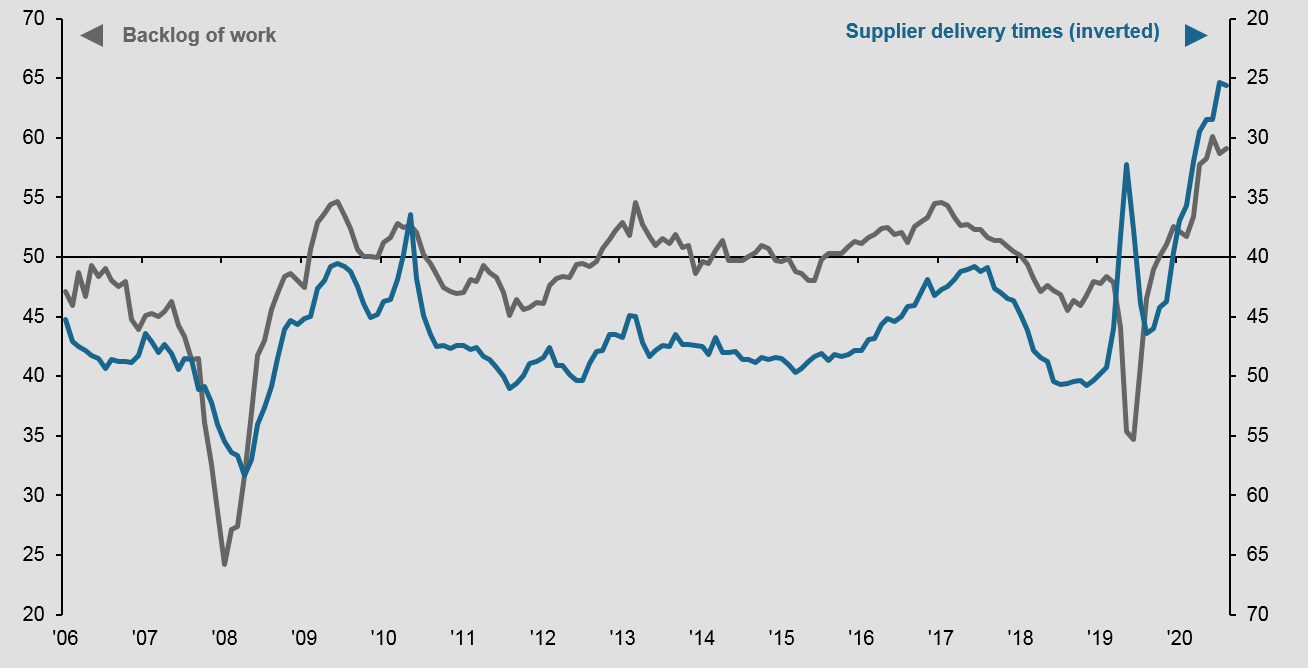

The rise in the Delta variant has dented corporate sentiment in recent months, weighing on near-term expectations for economic growth and a manufacturing industry beset with supply issues. The Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) for manufacturing has steadily declined over the past three months. Notably, the order backlog and delivery time sub-indices of the PMI for manufacturing remain at historically depressed levels, suggesting that material and component shortages will continue to weigh on manufacturing activity. Meanwhile, transport and shipping industries face their own shortages, which are exacerbating supply chain stresses.

As economies reopen, spending habits are likely to shift from goods to services, easing goods demand. However, many industries still need to replenish supplies, and the delayed global re-stocking cycle may support demand for inputs. While this is positive for the growth outlook and manufacturing sector more broadly, the downside is that supply chain pressures and the higher associated costs may persist for longer.

Central to the issues around disrupted supply chains has been access to semiconductors. The relentless trend toward digitalization, and now the electrification of many industries, created demand even as supply was modestly restricted. The lead times between semiconductor orders and when they are fulfilled have continued to be stretched as demand has increased. Lead times rose to 20 weeks at the end of July, compared to an average of 13 weeks since 2017. While the strength in demand is very supportive for the earnings outlook for semiconductor producers who have strong pricing power, the supply tightness is having clear impacts on companies further along the value chain. Automotive manufacturers in Europe, Japan and the U.S. have curtailed production due to semiconductor supply issues, with knock-on effects to other auto component suppliers. U.S. auto sales have fallen for the last three consecutive months.

The outcome of the semiconductor shortage has been an acceleration in onshoring capabilities and the self-reliance in production for this integral component to many industries. Both the U.S. and China have ramped up fiscal support for domestic production. This will actually benefit many of the world’s largest semiconductor companies, which will play a large role in this shift in production locations as new plants are established in the U.S., China and Japan. There is concern that this may result in an eventual oversupply of semiconductors—adding to concerns that some of the recent demand is hoarding rather than for final goods demand. However, it will also likely create a more assured supply base and a semiconductor industry that is less cyclical and more supported by longer-term themes such as electrification. This will allow the industry to better manage supply chain disruptions and fluctuations in short-term demand.

Business surveys continue to emphasize the significant delays in securing inputs to the manufacturing sector

EXHIBIT 1: DEVELOPED MARKET PMI SUB-INDICES BACKLOG OF WORK AND SUPPLIER DELIVERY INDICES

Sources: Markit, J.P. Morgan Economic Research, J.P. Morgan Asset Management.

Data reflect most recently available as of 26/08/21.

Investment Implication

The supply chain pressures are likely to linger longer than initially thought even if some pressures ease and COVID-19-related restrictions become less of a constraint as vaccination rates rise throughout Asia over the coming months. Global re-stocking means demand for final goods may remain fairly robust and is positive for the manufacturing sector and broader economic activity. It is worth noting that supply side pressures mostly affect the goods sector, and the services sector is likely to remain resilient. It is an important consideration for large developed markets where the services sector is a much larger share of the economy.

The ongoing disruptions to the global supply chain may also be interpreted as being an upside risk to inflation, but also a transitory one that is outside the control of central banks. In this respect, supply chain stress alone is unlikely to create a shift in policy settings. Persistent inflation pressures from higher wage costs and tighter labor markets are likely to dominate when it comes to the inflation outlook.

Meanwhile, corporate margins have been very healthy over the first half of the year as the earnings recovery nears its peak. Companies may start to feel pressure if they are unable to pass on rising input costs from both tightness in supply chains and higher shipping costs. Investors may wish to focus on companies that can maintain pricing power within their respective industries to protect margins.

When it comes to semiconductors, the persistence in demand bodes well for earnings outlooks. However, levels of investment and capacity vary between leading-edge chip technology and older technology. This may mean differentiating between downstream industries that use newer chips and those reliant on older technology where capacity and investment by semiconductor manufacturers may be limited.

0903c02a829b6918