Every two years, we take a close look at the performance of the private equity industry given its rising share of institutional and individual portfolios. Our findings this year: the private equity industry is still outperforming public equity, but this outperformance narrowed as all markets benefit from non-stop monetary and fiscal stimulus, and as private equity acquisition multiples rise. We examine manager dispersion, benchmarks, co-investing, GP-led secondary funds, the torrid pace of industry fundraising and manager fees in this year’s piece.

Introduction

The question of whether private equity outperforms public equity continues to be a hotly debated issue in investment finance. In the latest food fight, Steve Kaplan at the University of Chicago takes on Ludovic Phalippou from the University of Oxford. Phalippou is the author of “Private Equity Laid Bare”, has a podcast with the same name, and asserts that private equity managers have not outperformed net of fees. Kaplan takes issue with Phalippou’s time period selection, his definition of private equity and choice of small/mid cap benchmark and cites consistent (albeit narrowing) outperformance of venture capital and buyout funds over time. In this Executive Summary, we discuss the high-level conclusions from our biennial private equity review. The full private equity paper contains our complete analysis with a broader discussion of topics, including the Kaplan-Phalippou debate.

Buyout Performance

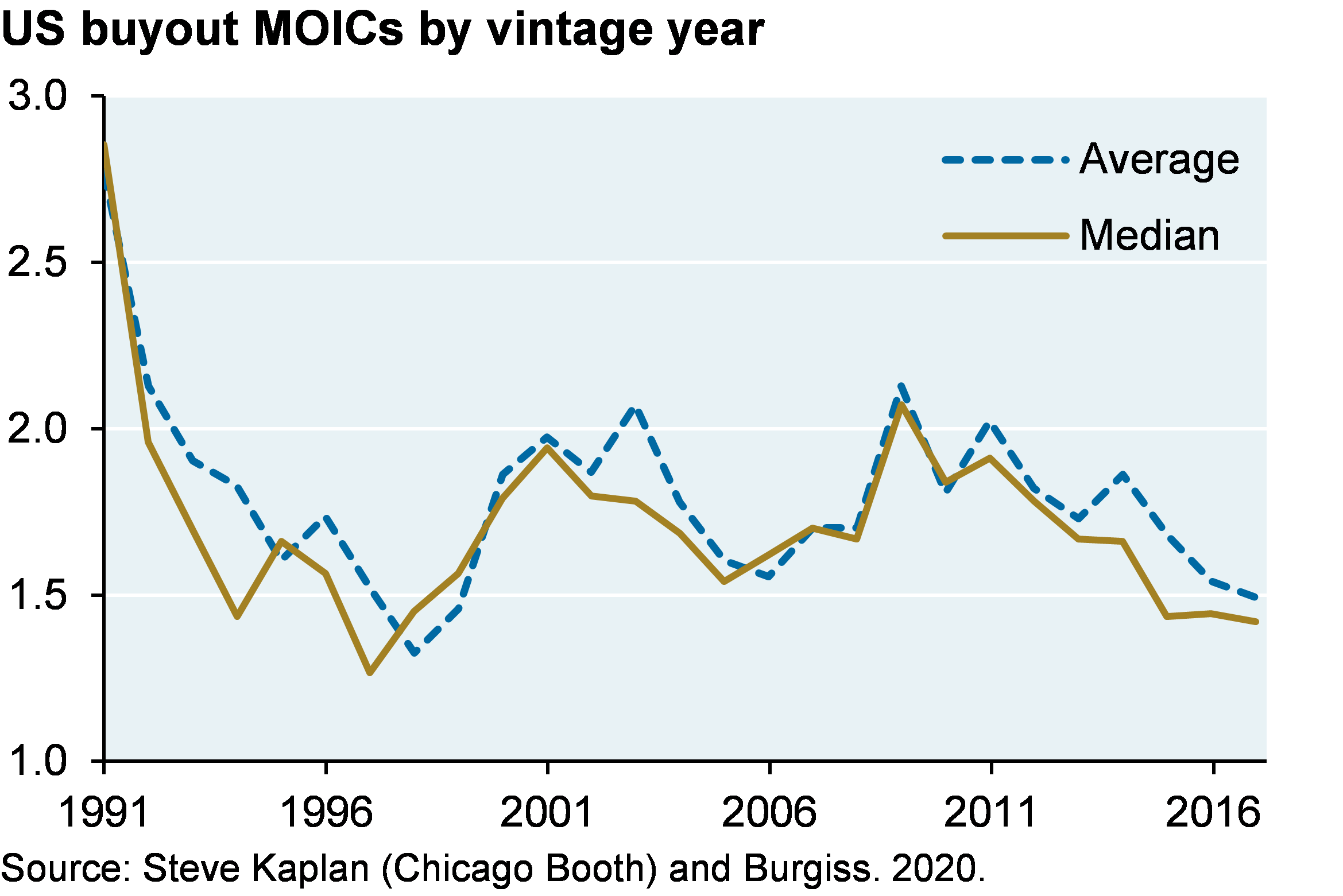

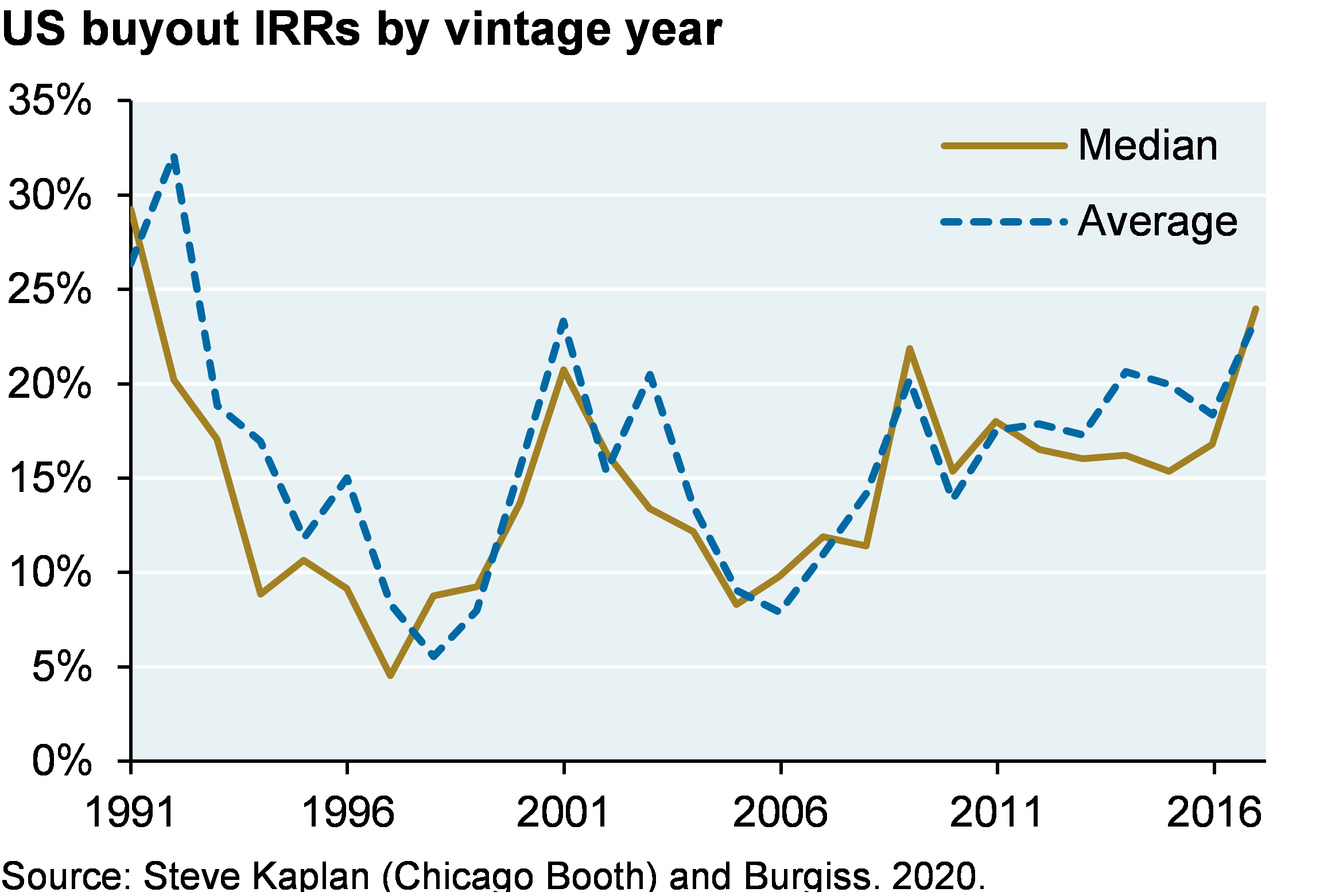

The charts below show average and median multiples of invested capital (MOIC) and internal rate of return (IRR) for buyout funds since the early 1990’s. MOIC is a simple measure of cash-in vs cash-out, while IRR is a time-weighted measure of return. Note how there’s only a small gap between average and median buyout manager results.

Before 2009, average MOICs and IRRs generally moved in tandem with each other. Since 2009, MOICs have been declining while IRRs have been rising. The primary reason: increased use of subscription lines, which allow managers to finance investments with bank loans and delay capital calls to LPs until later in the investment period. This practice increases the IRR of a fund at the expense of a small rise in MOIC, since LPs end up paying subscription line interest.

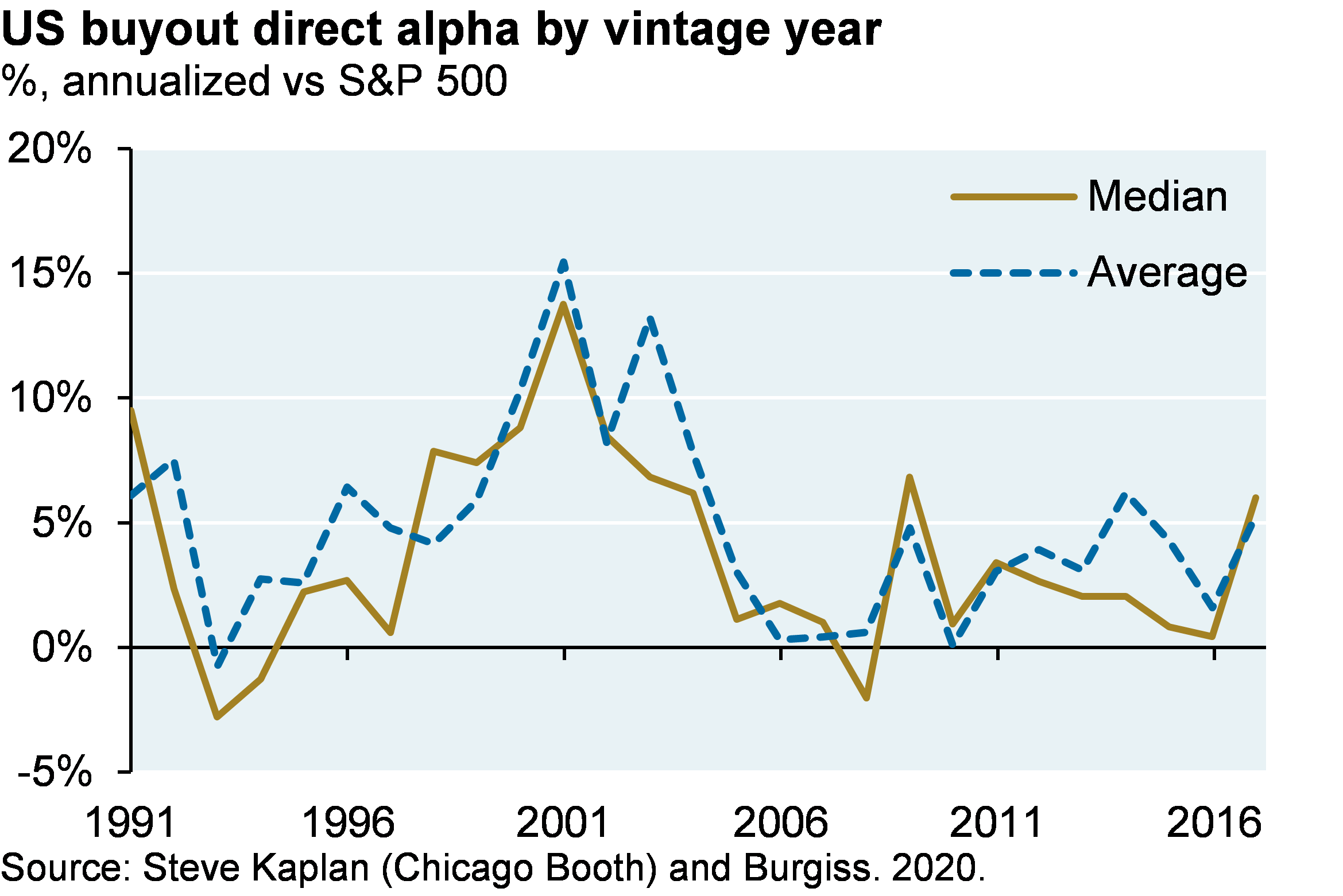

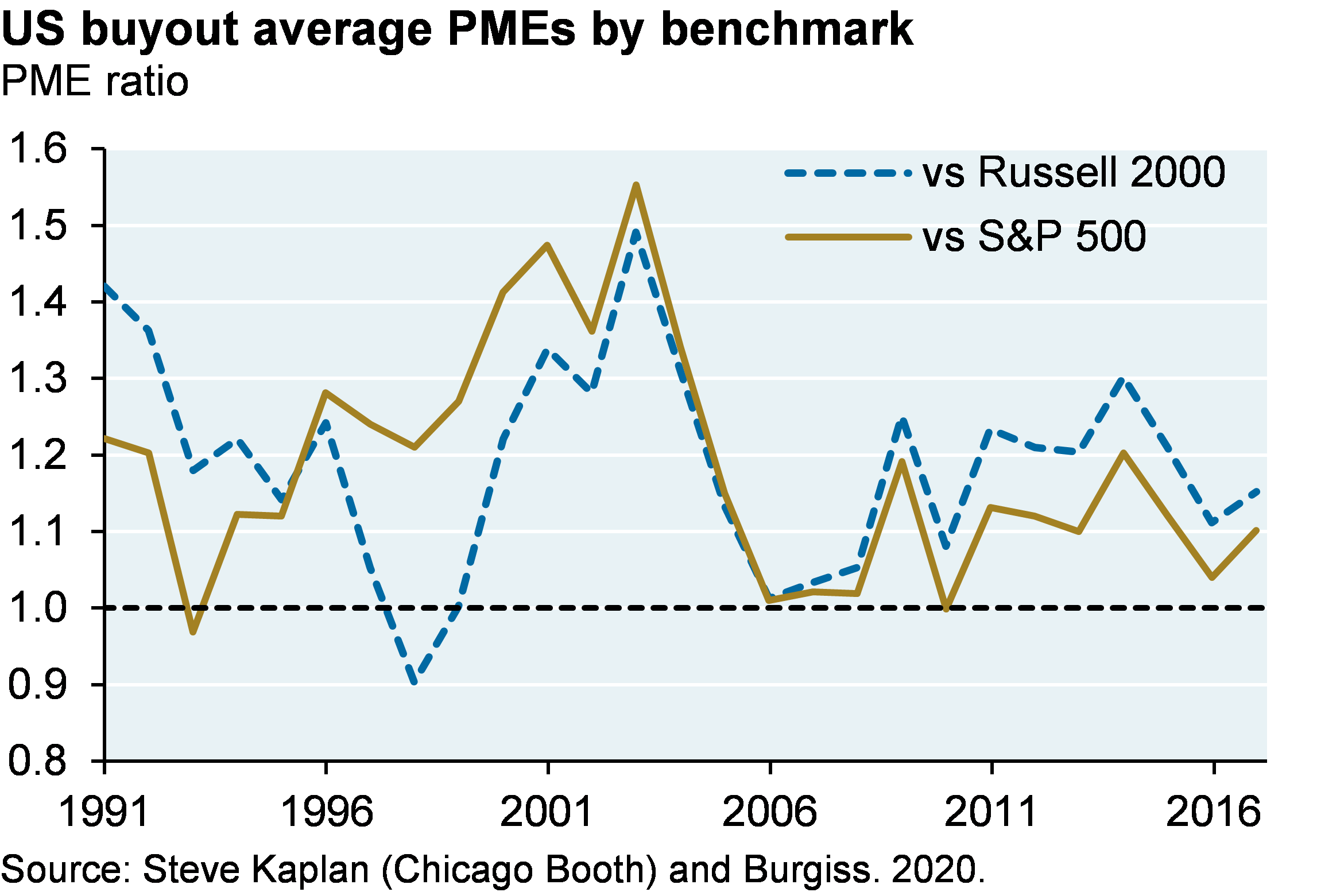

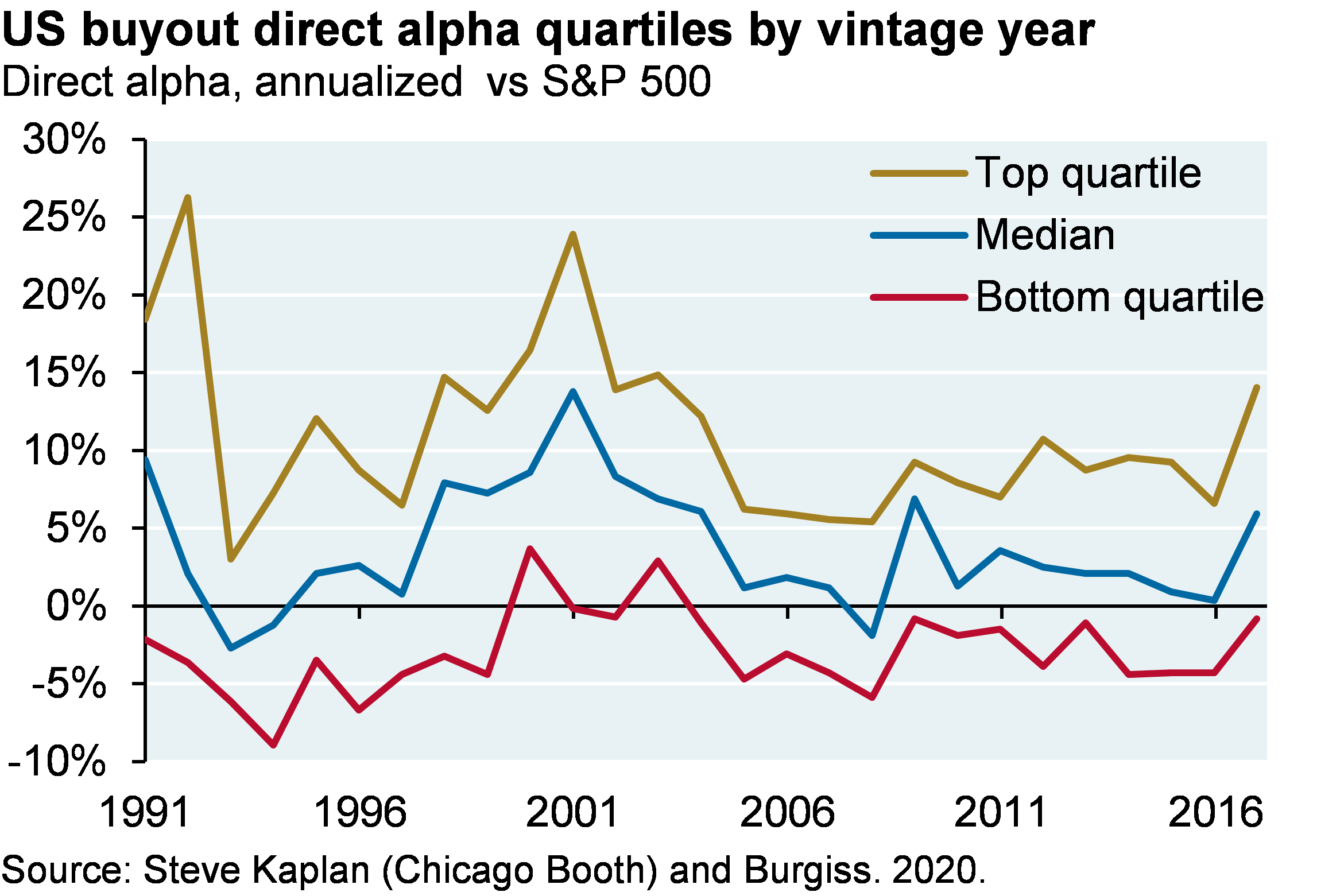

MOIC is not time weighted and neither MOIC nor IRR measures performance vs public equity. Analysts have converged on two concepts that address these shortfalls: the Public Market Equivalent ratio (PME) and Direct Alpha. PME compares private equity commitments and distributions to investments in public equity markets in the exact same time periods. The result is essentially an MOIC ratio of private equity performance vs the public equity benchmark used. Direct Alpha converts the PME into annualized outperformance in percentage terms. Note how average and median results for buyout are similar, as they were for MOIC and IRR. Since subscription loans impact the timing of upfront cash flows, they can materially boost Direct Alpha as well as IRR.

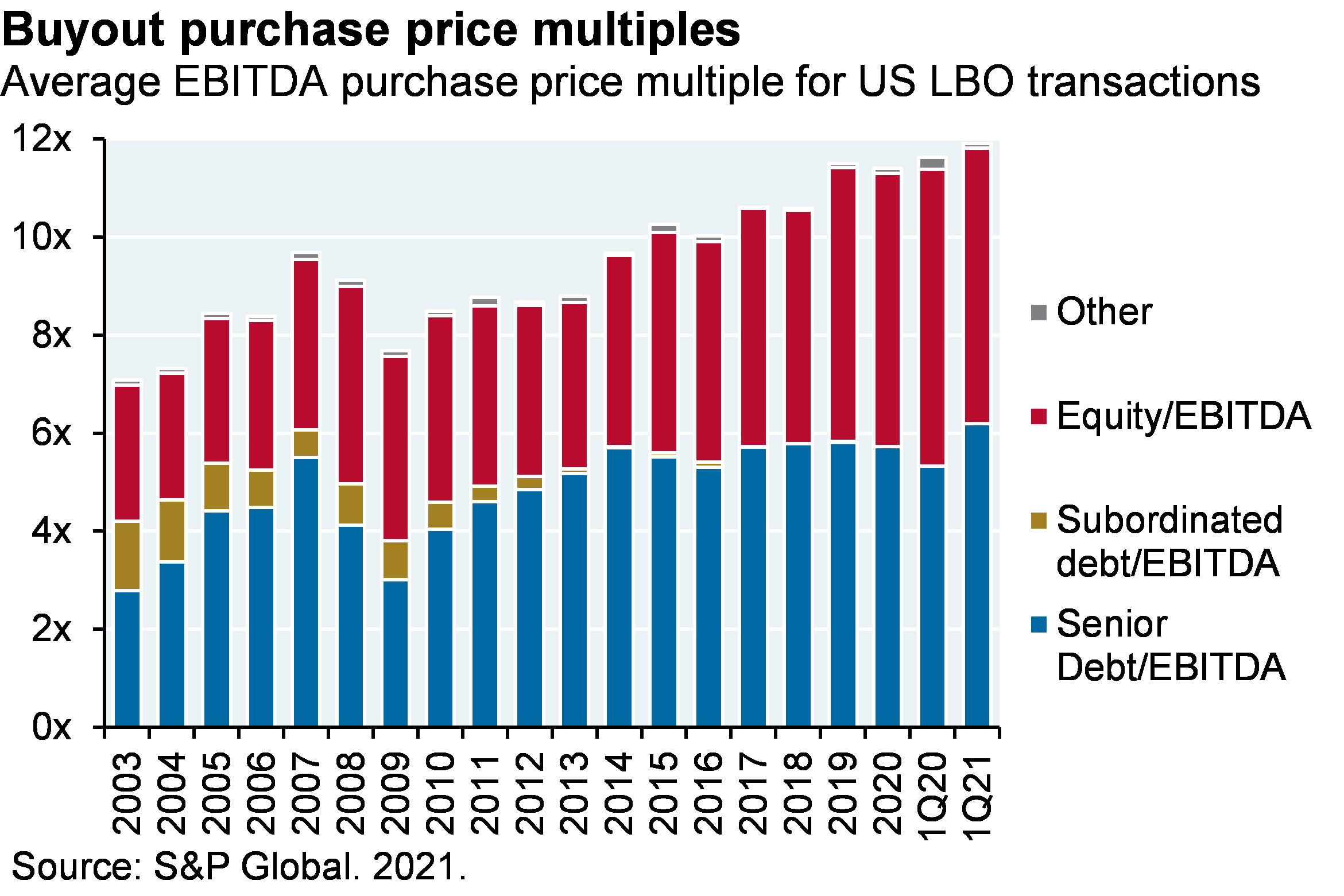

Why have relative buyout returns declined? After the financial crisis in 2008-2009, the Fed and other central banks adopted “maximum accommodation” policies. These policies led to a sharp rise in public equity valuations. In addition, buyout acquisition multiples have increased as the food fight over private companies continues, propelled further by the SPAC boom which we wrote about earlier this year. So, higher buyout purchase prices and better-performing public equities have reduced buyout outperformance.

Are the recent annualized 1%-5% excess returns over public equity markets since 2009 enough given the illiquidity of private equity? Rather than apply an abstract derived cost of liquidity, most investors will judge for themselves whether these returns suffice based on their consistency and magnitude.

Buyout funds: what is the “right” buyout performance benchmark?

Some analysts are reluctant to use the S&P 500 as a benchmark for buyout managers that invest in smaller companies. While US buyout deal sizes have been rising, the average buyout is still much smaller than a typical large cap company. The median S&P 500 market cap is $21 billion, the average US buyout is $2.5 billion and the median Russell 2000 market cap is $1.1 billion. In any case, the chart below shows PMEs using the Russell 2000 instead. The results reflect the relative performance of the S&P 500 vs the Russell 2000 over time.

Buyout manager dispersion

Average/median managers have consistently outperformed, but what happens if you pick a below-average buyout manager? Since 2010, the gap between top and bottom quartile managers has narrowed compared to prior decades, and the degree of underperformance for bottom quartile managers is pretty modest.

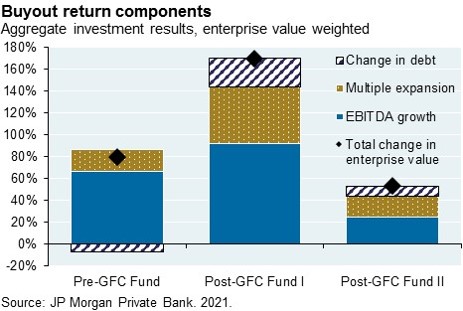

Drivers of buyout performance

While cash flow data sourced from limited partners is a reliable way to measure performance of private equity funds, it does not allow a closer look under the hood to see what drives that performance. We asked one of the larger buyout managers we know for company-specific data for three consecutive buyout funds they managed. We decomposed the change in enterprise value into three sources: cash flow (EBITDA) growth, changes in valuation multiples and change in debt levels. In each case, operating cash flow improvements at the company accounted for more than half of the total change in enterprise value, and for more than the impact of multiple expansion. This is not meant to be indicative of the industry as a whole, but it does illustrate that operating improvements can play a primary role in generation of returns.

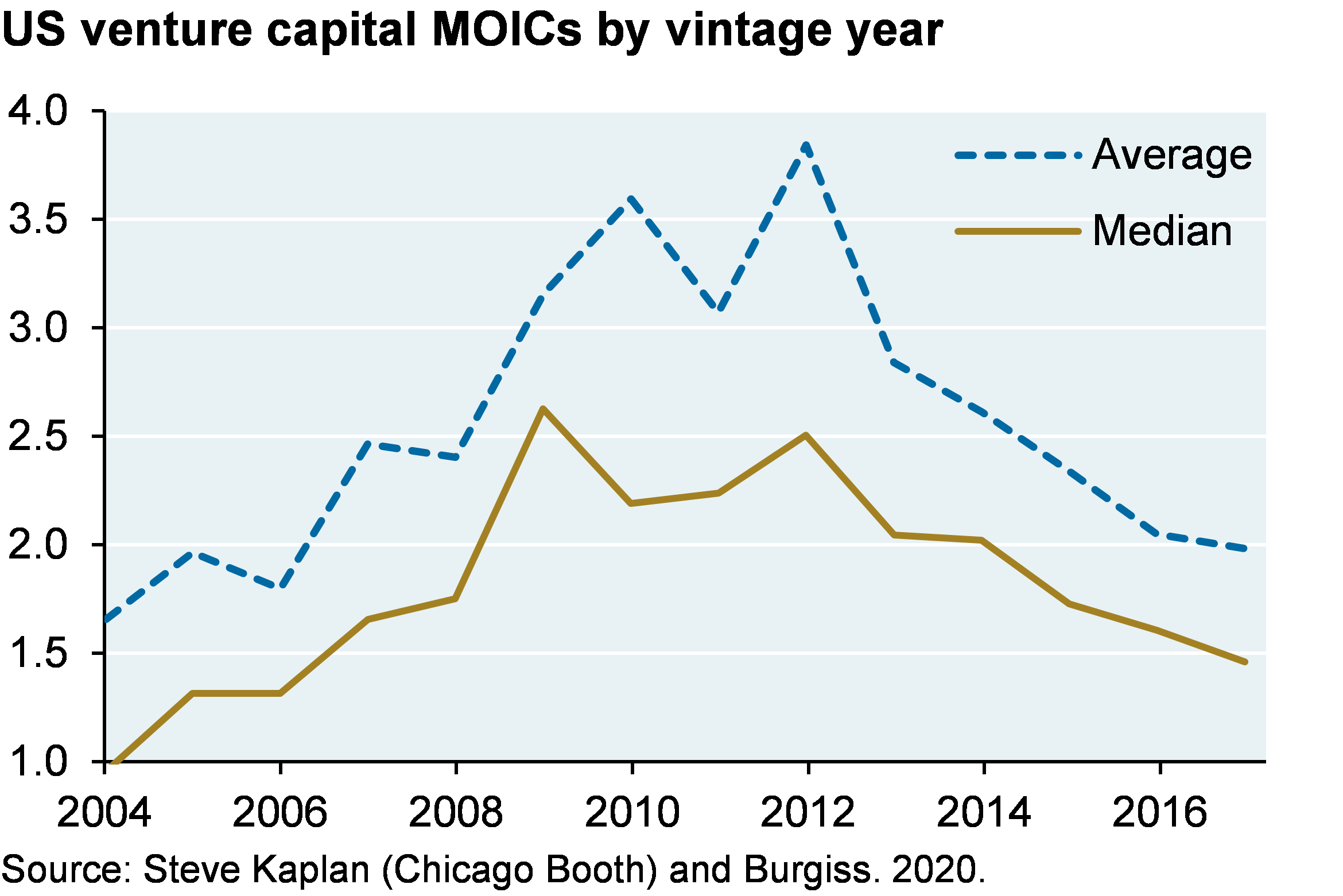

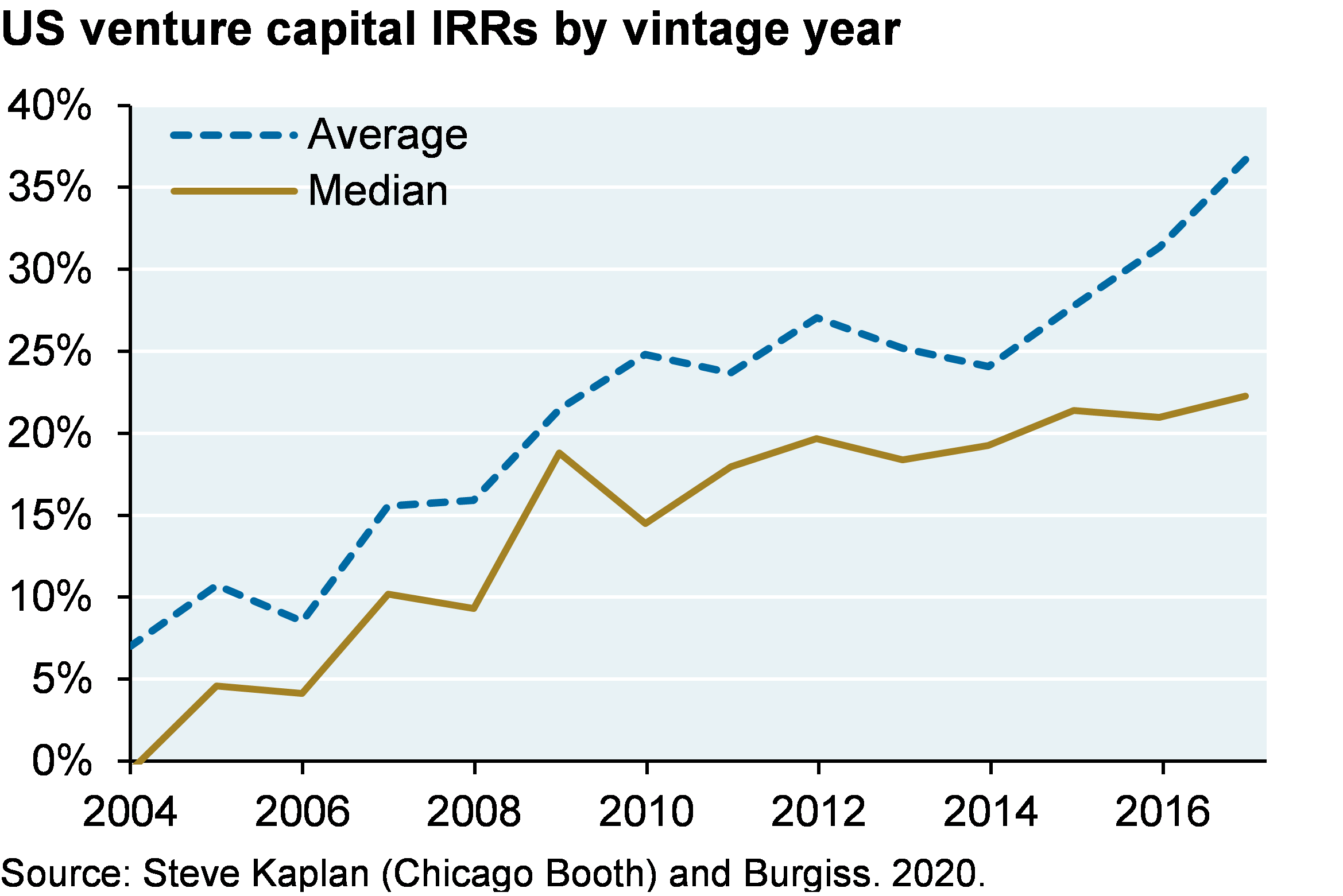

Venture capital performance

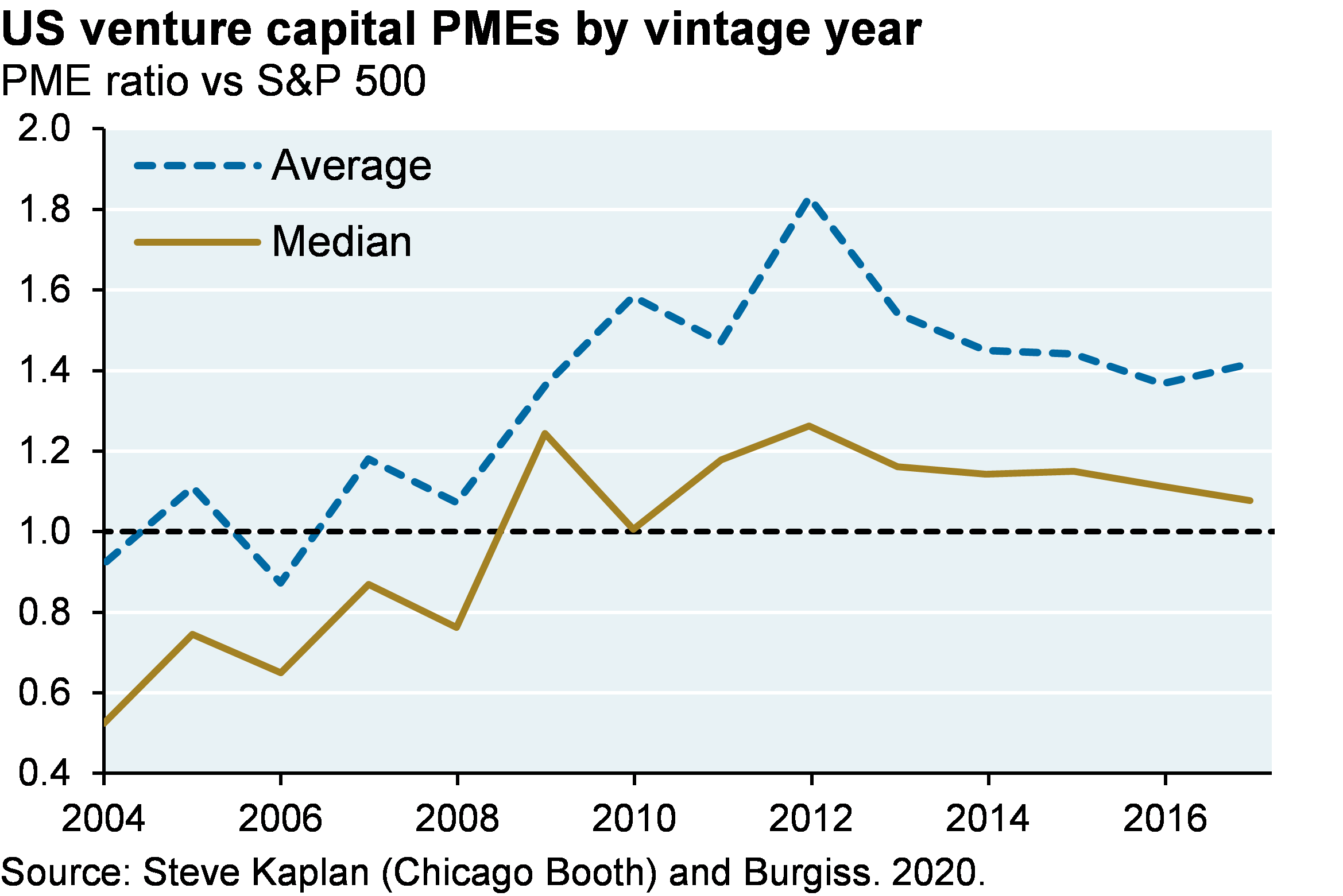

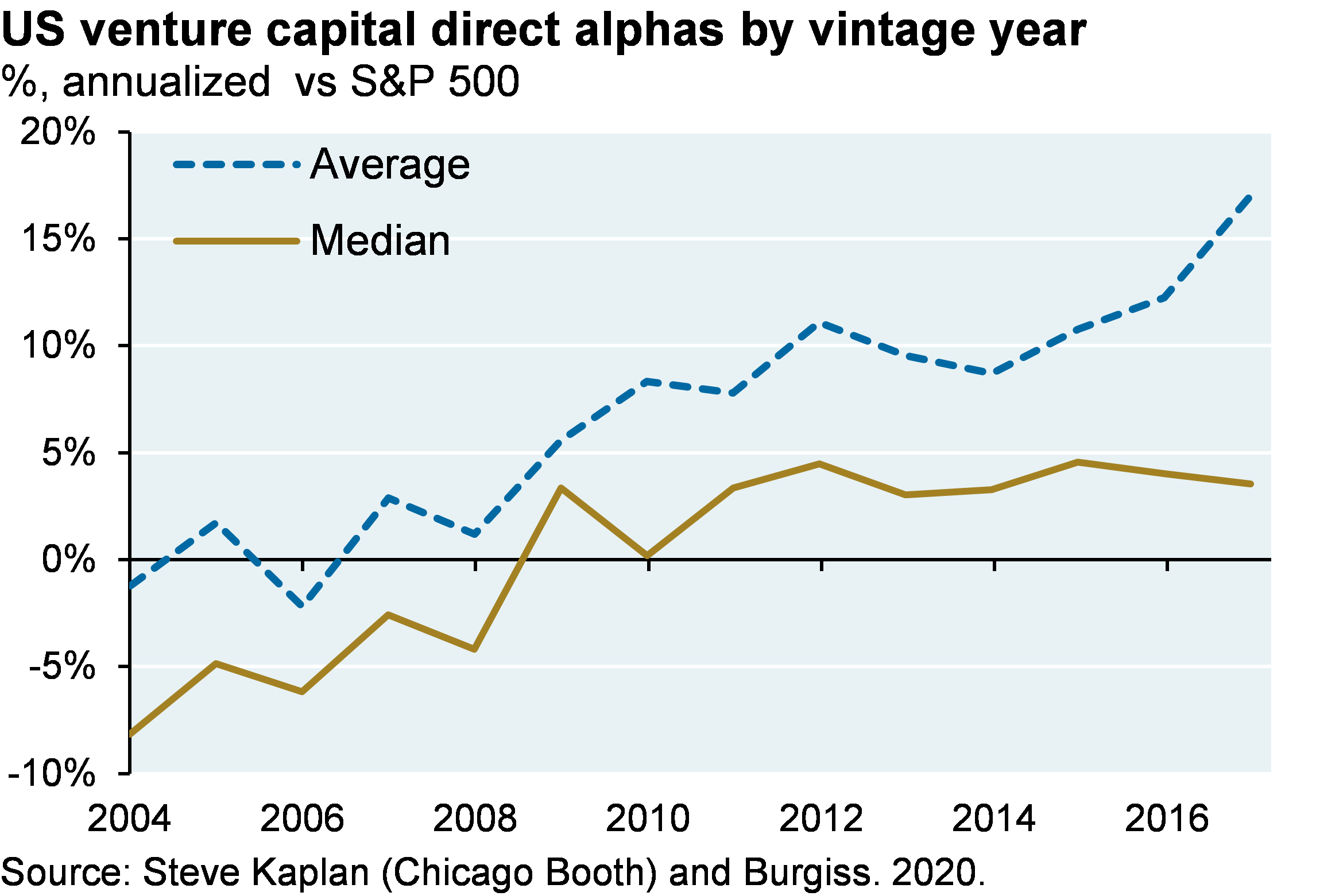

As with buyout managers, VC manager MOIC and IRR also tracked each other until 2012 after which a combination of subscription lines and faster distributions led to rising IRRs despite falling MOICs. There’s a larger gap between average and median managers than in buyout, indicating that there are a few VC managers with much higher returns and/or larger funds that pull up the average relative to the median.

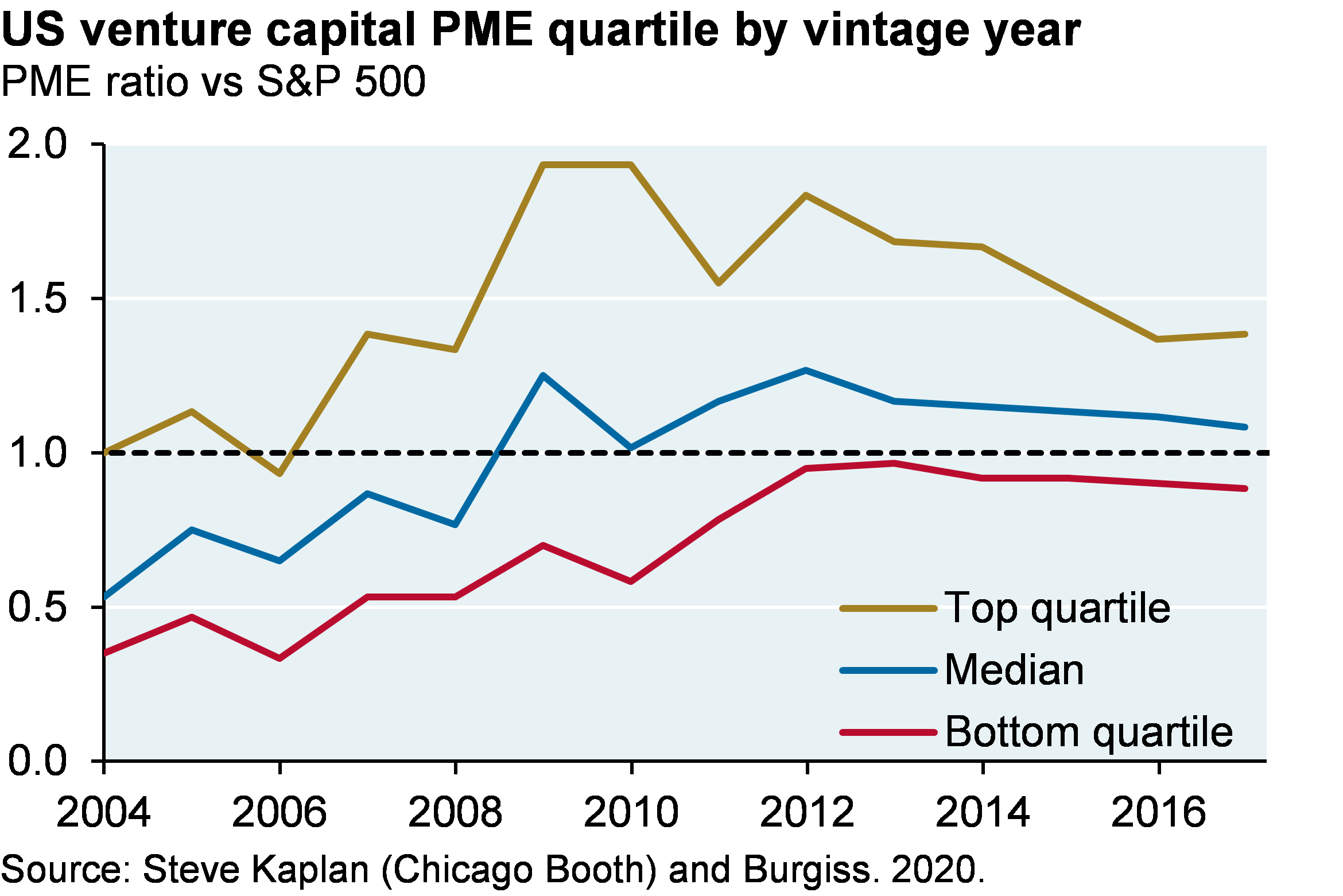

VC managers have consistently outperformed public equity markets when looking at the “average” manager. But to reiterate, the gap between average and median results are substantial and indicate outsized returns posted by a small number of VC managers. For vintage years 2004 to 2008, the median VC manager actually underperformed the S&P 500 pretty substantially.

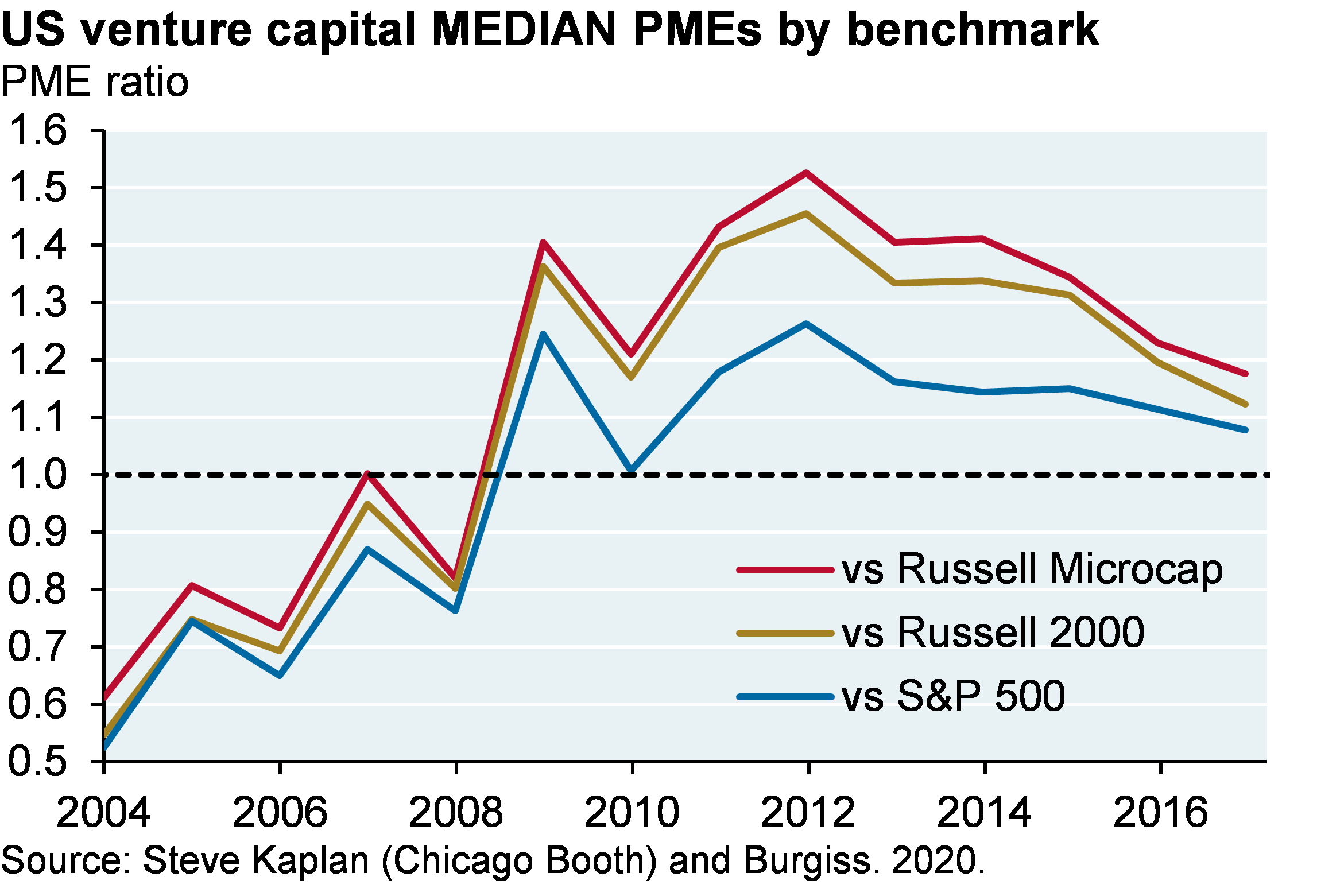

Venture capital: performance benchmarks and manager dispersion

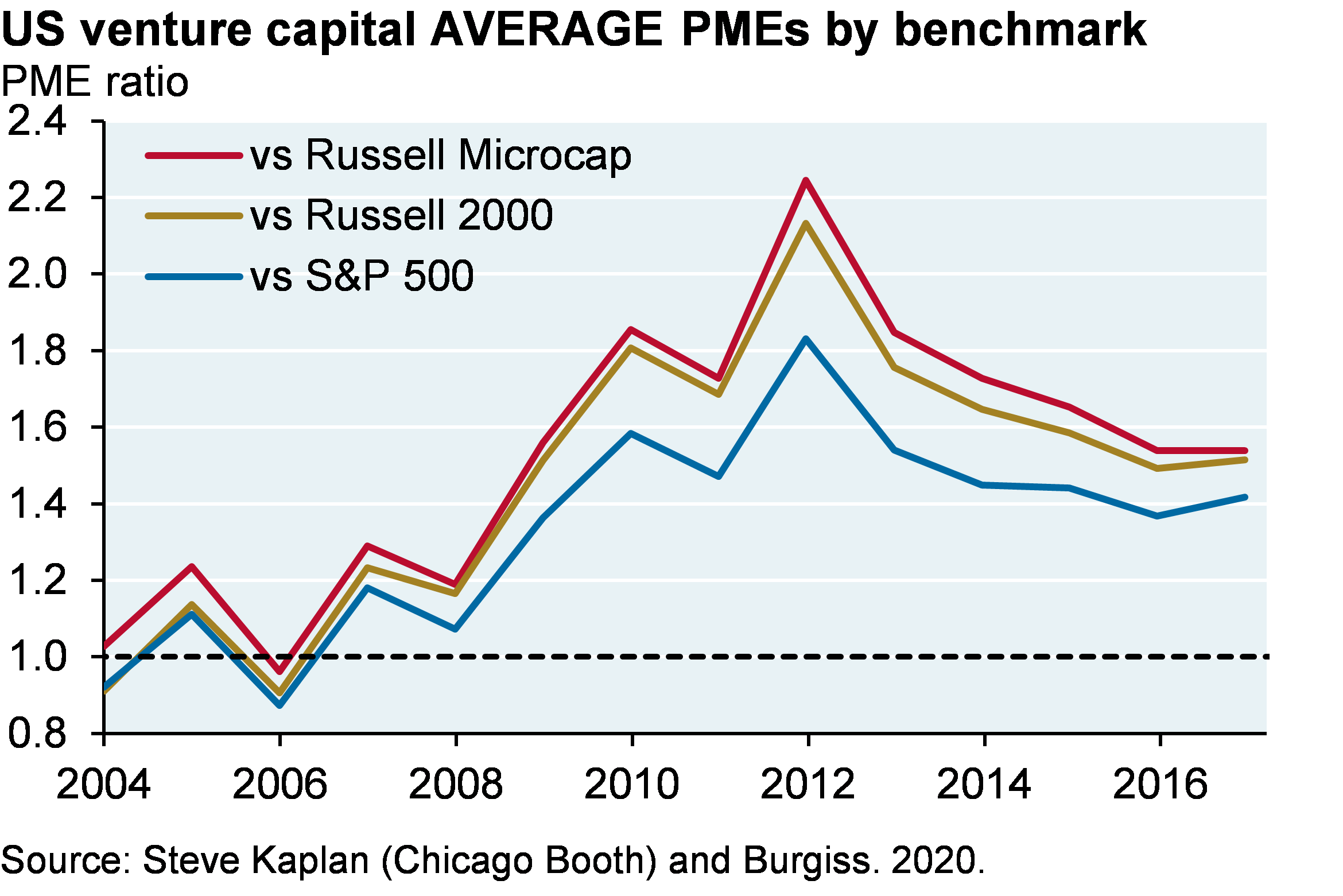

One could make an even stronger argument that the S&P 500 is not the right benchmark for venture capital given much smaller deal sizes. The first two charts show average and median PME ratios for VC using different benchmark options. Since the S&P 500 outperformed the Russell 2000 Index, the Russell 2000 Growth Index, the Russell Microcap Index and most other US equity benchmarks since 2010, using a different benchmark than the S&P 500 would simply make venture outperformance look larger since that date.

As for manager performance dispersion, VC trends are similar to buyout. Since 2010 the gap between top and bottom quartile VC managers has narrowed and bottom quartile VC manager underperformance vs public equity is very modest. To be frank, I was expecting much worse from bottom quartile VC managers.

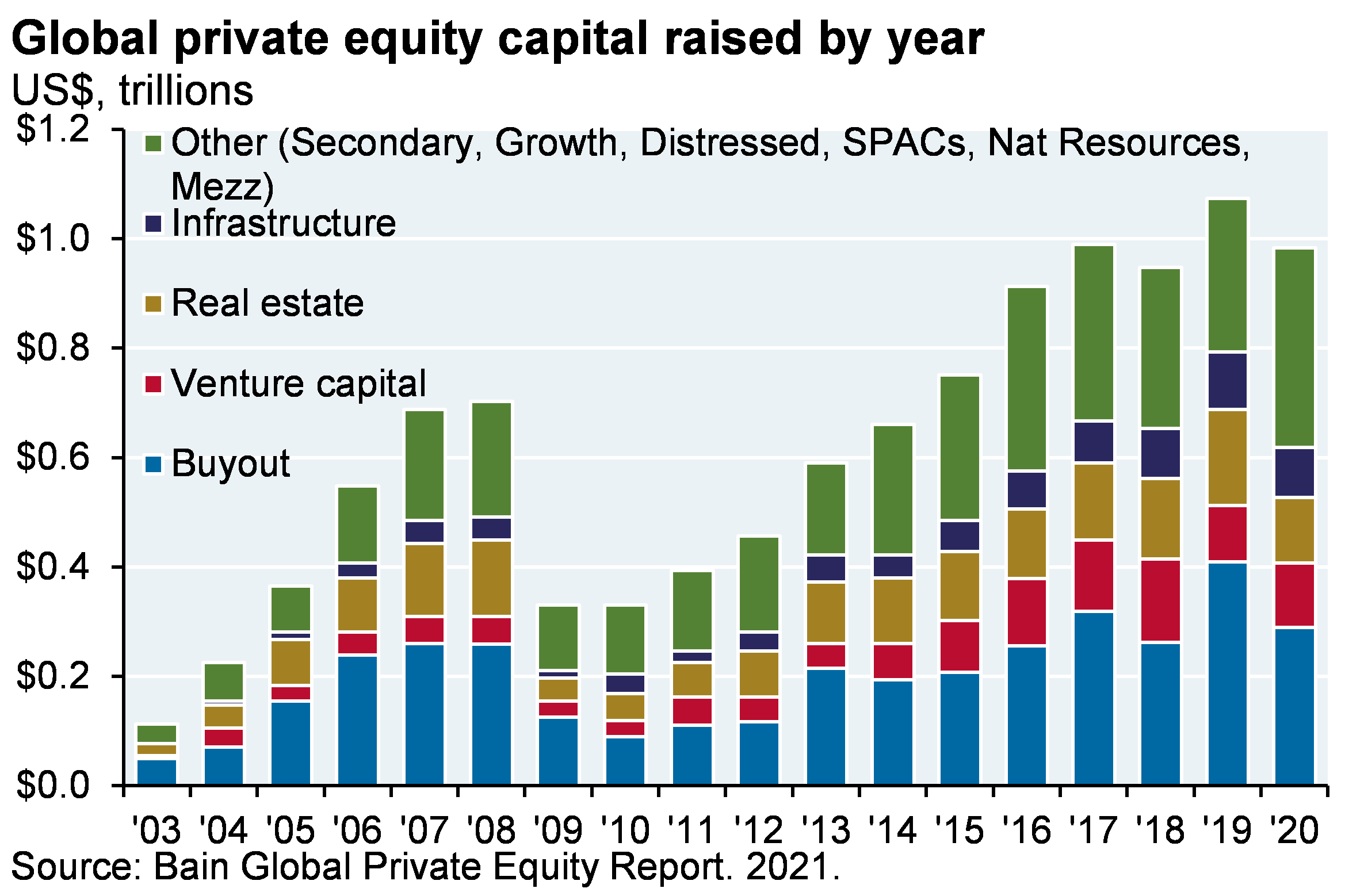

Fundraising and the pace of investment

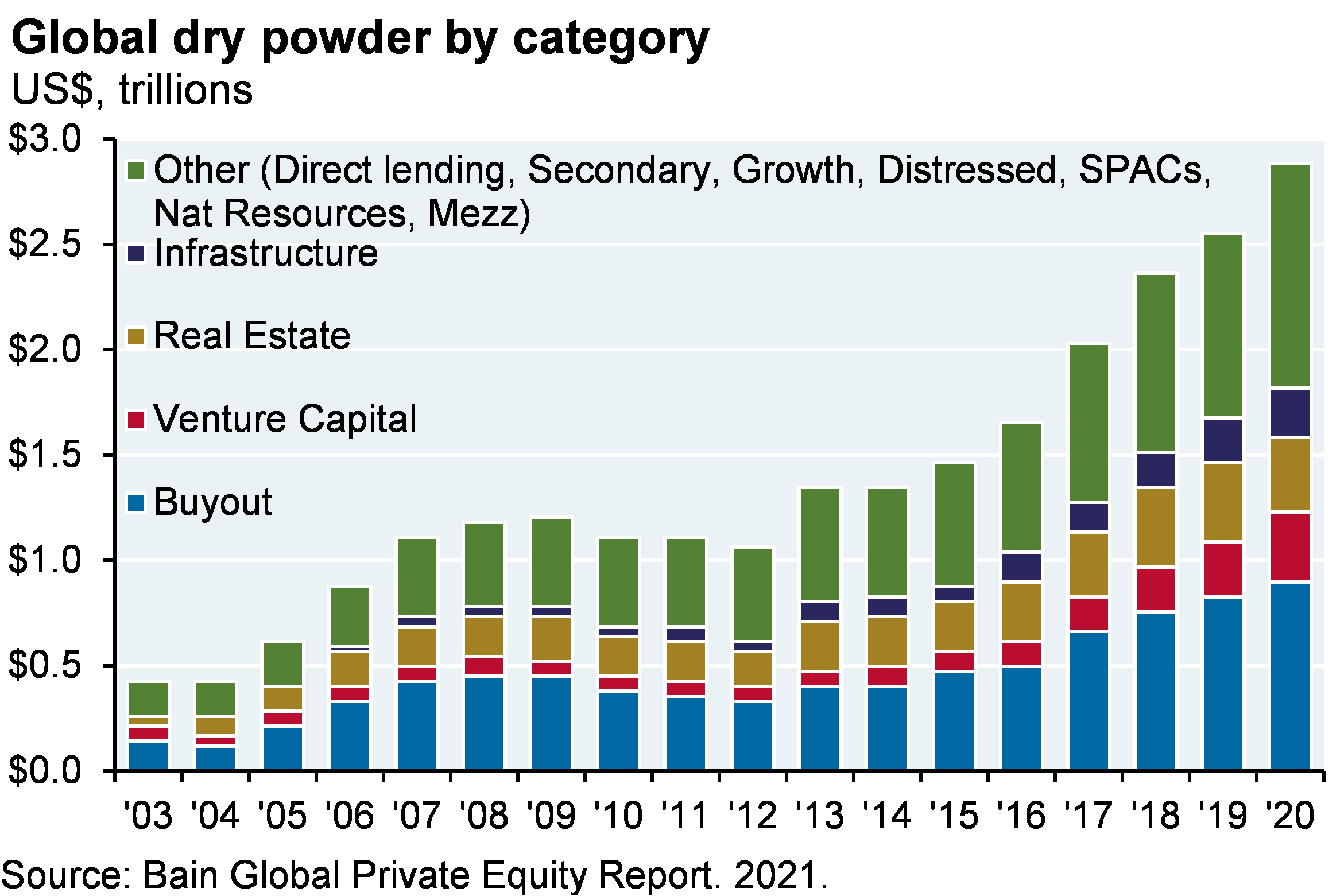

- Since the pace of new investment has trailed fundraising, global “dry powder” has exploded since our last analysis, rising from $2 trillion to ~$3 trillion. However, this figure includes all private equity categories and not just buyout and venture capital. For the latter two categories, dry powder is closer to $1 trillion

- Increased use of subscription lines also overstates the “real” amount of undrawn and committed capital. The latest estimates indicate $500 billion in subscription lines outstanding, which is a meaningful portion of the increase in global dry powder since 2012

The full private equity paper contains our complete analysis, including the following:

- Growing size of average buyout and venture capital transactions

- Return dispersion of buyout vs venture, real estate and private credit

- Detailed decomposition of buyout fund drivers of enterprise value

- Secondary private equity funds and the rise in GP-led transactions

- How are gains on venture-backed companies split between VC investors and post-IPO investors?

- Return and downside risk benefits from co-investments

- The pace of capital calls vs distributions

- Fundraising vs market capitalization for buyout and venture capital

- Discussion of private equity fees and incentives

- The latest academic private equity research (performance persistence, investor timing and post-IPO holding periods)

- Return dispersion on buyout and venture transactions within commingled funds

- Sources of private equity performance data

- Appendix on methodology for IRR, Direct Alpha, cash flow timing and subscription lines

Food Fight: 2021 Private Equity Update

Every two years, we take a close look at the performance of the private equity industry given its rising share of institutional and individual portfolios. Our findings this year: the private equity industry is still outperforming public equity, but this outperformance narrowed as all markets benefit from non-stop monetary and fiscal stimulus, and as private equity acquisition multiples rise. We examine manager dispersion, benchmarks, co-investing, GP-led secondary funds, the torrid pace of industry fundraising and manager fees in this year’s piece.