I have always been impressed with the notion that accounting can be as much of an art as a science. There is so much that is open to interpretation and creativity. While there are some authoritative standards, there are also a fair amount of practices that are commonly accepted which has given way to the doctrine of GAAP, also known as Generally Accepted Accounting Principles. It struck me that we may have reached a similar state in Central Banking known as GAMP or Generally Accepted Monetary Principles. What seemed like unconventional and bizarre monetary policies in the immediate post-crisis world, have come to look generally accepted, if not pedestrian. The tools deployed over the past decade are no longer temporary, but are now a permanent part of a Central Banker’s tool kit. How did we get here? What are the risks? What does this mean for investing in the markets? These are all good questions, but I want to go back in time and get a running start into this discussion!

It used to be that monetary policy was all about interest rate targeting. Set the correct deposit rate and watch it ripple across the yield curve into the funding cost of any borrower and the opportunity cost of any saver. If a central bank wanted to lean against growth and inflation from running too hot – raise rates. If they wanted to promote growth and inflation – cut the deposit rate and relieve some of the pressure with a lower funding cost across the ecosystem. With just one straight-forward tool, I remember when the Federal Reserve (Fed) would move interest rate targets around based on how it wanted to prioritize growth, inflation and the dollar. Life for a central banker was so simple back then….although the markets were arguably quite a bit more volatile.

Fast forward to the Great Financial Crisis and suddenly new tools were needed with far greater capabilities than only moving deposit rates around. Quickly ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) and QE (quantitative ease) became part of the central banker tool kit. When first implemented outside Japan in the wake of the crisis, money printing at a cost of 0% in order to buy government bonds was seen as extreme, unconventional and certainly only a temporary policy tool. The distortions to markets grew as ZIRP transformed into NIRP (negative interest rate policy) and purchases extended to mortgages, corporate debt and equities (in the case of the BOJ). It was reasoned that unless these tools were temporary, significant inflation bubbles would form.

But that has not happened. These tools are still present, but the bubbles are not. There is a combination of denial, confusion and anger about their lingering existence and potential longer term impacts. In fact, I just met with a former central banker who still decries their very existence, despite much evidence that suggests that they have helped the recovery and done little of the harm that was originally advertised.

With the unconventional policy now proving to be eternal, we believe that we have entered a new, modern world of central banking defined by GAMP….Generally Accepted Monetary Principles. Not only have central bankers embraced these tools as permanent, but they have begun to experiment with newer ones. The Fed has opined on inflation targeting through a cycle whereby core inflation could run above the 2% target during an expansion to make up for ‘lost’ inflation during recessions. In fact, to truly make up for lost inflation since 2007, core PCE would need to run at 2.5% for the next 9.5 years! In this context, the bar for additional rate hikes should be quite high in this cycle. And, if the Fed doesn’t like the message a potential inversion of the yield curve is sending to the markets, they now have the ability to manage the balance sheet run-off and subsequent reinvestments to influence the curve. Why not Quantitative Tightening (QT) on the mortgage holdings and Quantitative Ease (QE) on the front end of the Treasury curve? Essentially, their own version of operation reverse twist.

Permanently adopting these new tools is not only limited to the U.S. and the Fed. The European Central Bank (ECB) has indicated that it might be open to tiering of the official deposit rate – a mechanism to help mitigate the impact of negative interest rates on financial institutions. Throw in another round of Targeted Long Term Repo Operations (TLTRO), Optimal Yield Curve Control in Japan, and Currency Intervention etc…..suddenly, the definition of Generally Accepted has changed forever.

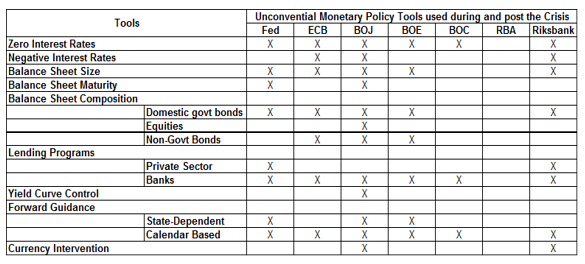

Listed below are examples of new tools that have been deployed since the financial crisis, and by whom:

To be fair, this is not the first time some of these “unconventional tools” have been deployed, although the intent and motivation of past central bankers was unique compared to more recent times. In the 1960’s, the Federal Reserve and U.S. Treasury engaged in ‘Operation Twist’ to keep long term borrowing rates low and encourage investment while also attempting to discourage capital outflows and the impact to the dollar due to potential gold outflows. From 1931 to 1937, the Swedish Riksbank became the first central bank to explicitly introduce price level targeting when it was relieved of its legal obligation to convert its notes into gold on demand and was struggling with deflation and an economic depression. The regime was not long lived because following the depths of the depression and the start of World War II (WWII), the central bank once again became subordinate to fiscal policy initiatives. Similarly, in the U.S. between the 1940’s and 50’s, the Federal Reserve periodically intervened in the long-term Treasury market by using interest rate pegs to lower borrowing costs in order to fund wars. While the buying of debt directly from the Treasury was prohibited at the time, an amendment to this rule was made during WWII allowing for a $5 billion wartime exemption.

Are there risks to unconventional tools becoming mainstays of monetary policy? Almost certainly if they are not properly used. The list of consequences if policy tools are used inappropriately or are no longer in the hands of an independent influence is long and concerning: asset bubbles may form, inflation may surge and the moral hazard of the end to fiscal discipline is a very real possibility. The current fascination with Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) highlights the fragility of GAMP if a certain version is finalized ……with emerging economies being referenced as the poster child for how it all ends in tears. On the other hand, Japan is an example of how another version of GAMP can be used over an extended period of time without grave consequences. I know the debates here are endless (I’ve had my fair share over the last month) and each economy has its own particular circumstances which allow versions of GAMP to succeed or fail.

Most important for us as investors is to welcome GAMP and the new tools being broadly deployed as part of the principles of unconventional policies becoming conventional. Essentially, these policies are not going away and we must understand and embrace the opportunities these policies create in the markets wherever they may occur. Yes, I would have liked the Fed to keep raising rates to 3%, to run down its balance sheet for another couple years, for the ECB to move deposit rates back above 0% and run down its balance sheet, and for the BOJ to start its own version of normalization. It would have likely meant that we could all be investing at much higher yields instead of the paltry levels we’re left with today. But it didn’t happen and central bankers have correctly recognized this is not the time to push recklessly towards these outcomes of more “normal” policies. On the contrary, the central banks are telling us that where we are today is now normal. With the pressure of further normalization now eliminated and the global expansion likely to continue as a result, investing in risk assets makes sense especially as the focus on future growth and inflation has shifted to fiscal policy.

I, for one, embrace the new GAMP. I applaud the willingness of central banks to experiment in an effort to moderate a significantly larger and more complex global ecosystem. I have my own views on which tools are more effective or ineffective, but ultimately I need to tie that back to investment drivers and opportunities. I encourage all investors to stop burning time and energy fretting about the new central banker GAMP doctrine, and instead interpret, model and study them in an effort to generate better returns.