In recent months, the macro view driving our positioning has been pretty simple: the flow of central bank balance sheet expansion is still the dominant force driving markets – both risk markets as well as interest rates. As long as the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan (BoJ) continue to grow their respective balance sheets much more rapidly than the Federal Reserve (Fed) is shrinking its own, asset prices are likely to continue to remain buoyant and interest rates relatively contained. Admittedly, it has been difficult to embrace this, given lofty valuations everywhere, and the relentless onslaught of chaotic political and policy headlines. Adding to the difficulty, embracing this view also means tolerating a sort of expiration date, because the underpinnings are set to reverse.

If net positive balance sheet flow (QE) creates asset price inflation and exerts a positive impulse on deposit growth, then it follows that net negative balance sheet flow (QT) ought to run both of these processes in reverse. This simply means that markets will transition from a period of loosening financial conditions to one of tightening financial conditions, and the shift is driven by balance sheets, not policy rates. After all, we’re four hikes into the US tightening cycle and financial conditions are still trending looser for now. The annoying fact of the matter is that ideal investment positioning during a period of loosening financial conditions is more-or-less the opposite of ideal positioning during a period of tightening financial conditions, almost by definition. So, what to do? When to reposition? In short, not just yet, but we’re close.

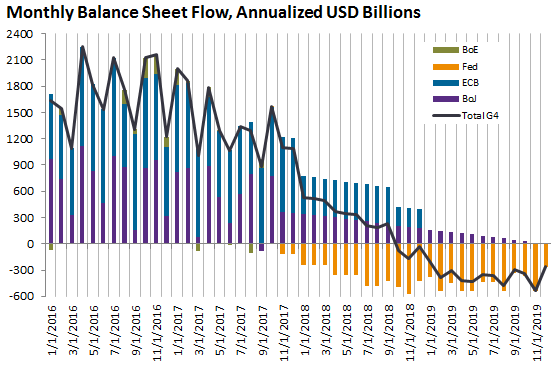

There is still some uncertainty surrounding when the net global QE flow moves arithmetically negative. The Fed’s QT path in the US is well-telegraphed, and the ECB has committed to a level 30 billion euros per month of QE from January 2018 until at least September 2018. The BOJ’s expansion will depend on the specifics of the yield curve control policy, but reasonable expectations suggest tapering purchases over the next two years. Though each of these three banks would modify these paths in response to economic developments, late third quarter of 2018 looks to be the most likely point at which the net flow moves negative, and it’s unlikely to be sooner than the summer of 2018. (Chart)

Source: Bloomberg,J.P. Morgan Asset Management; as of 11/24/2017. Assumptions: The Fed tapers reinvestments starting in October 2017 as per the assumptions outlined in the addendum to policy normalization released by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) at the June 2017 meeting. The Bank of Japan (BoJ) tapers purchases to zero by end of 2019; the Bank of England (BoE) does not make any additional QE purchases; The European Central Bank (ECB) purchases 60bln euros of securities through end of 2017, 30bln euros from Jan 2018 to Sep 2018 and 15ln euros from Oct 2018 to Dec 2018. All monthly figures represent annualized pace of purchases. Forecasts use current spot FX rates (November 2017). Historical FX Rates are used for realized/actual monthly flows through September 2017. Forecasts, projections and other forward looking statements are based upon current beliefs and expectations. They are for illustrative purposes only and serve as an indication of what may occur. Given the inherent uncertainties and risks associated with forecasts, projections and other forward statements, actual events, results or performance may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated.

I don’t think the precise date is especially important, because I think the transition to financial conditions tightening will begin to occur prior to the actual sign change on net global QE flows, for several reasons. First, the US Fed balance sheet impact is directly relevant for US asset prices and system-wide liquidity, whereas foreign central bank flows are only indirectly related through cross-border capital flows. Therefore, the US QT (which is already negative) should be more impactful dollar-for-dollar than the offsetting foreign QE. Secondly, the market on some level should be able to price the impact ahead of time, at least slightly. The asset price inflationary impact of balance sheet expansion is generally a contemporaneous effect, in that cash equivalents are created, they immediately seek investable assets, and thereby incrementally establish a new supply-demand equilibrium price for cash-versus-assets. Once new holders of cash are within a window of time in which they’re willing to hold the incremental cash (anticipating global liquidity levels are set to decline) in lieu of buying assets, asset prices should begin to decline. The length of that window of time is not zero. And thirdly, significant disagreement remains regarding the relative importance of the stock, flow, or impulse of the central bank balance sheets. Obviously I’m in the flow camp, but the debate is intellectually honest and not yet settled. The Fed has successfully established a narrative that the aggregate size or stock of their balance sheet is stimulative, so a slightly smaller sheet is merely slightly less stimulative. Their message is a powerful one, and has been effective in influencing investor behavior: uncertainty has so far postponed advance pricing of any negative impacts of QT. To the extent investors abandon the debate and settle on the flow impact, either because of real cash shortages or because an exogenous shock merely casts doubt on the alternative with no actual linkage, the transition timing may speed up as a larger portion of the investor universe embraces the tighter financial conditions under QT.

If I’m wrong about QT’s impact on financial conditions, or if the impact is nullified or delayed by a particularly successful tax reform plan – one which succeeds in durably lifting productivity – then the period of carry-friendly loose financial conditions persists for quite some time longer – multiple years perhaps.

I’m not holding my breath on productivity gains, but we won’t know either way until the second half of 2018 at the earliest. If a reconciled tax bill passes in a matter of weeks though, the optimistic rhetoric on jobs, growth, and productivity will be deafening. The resulting extension of the risk rally may coincide nicely with my preferred timing to prepare for tighter financial conditions: Q1 2018.

My original Stock, Flow or Impulse? blog post was published in September 2017.