The ECB’s strategy review: Actions speak louder than words

2020/02/03

Jason Davis

Policymakers tend to be incremental. The last European Central Bank (ECB) strategy review in 2003 changed the inflation target from “below 2%” to “below but close to 2%.” Could it be the case that 17 years later the ECB make the big leap from “below but close to 2%” to “2%”?

It is entirely possible that this is the only significant official result of the upcoming strategy review. However, with the ECB quickly running out of tools and inflation still some way from their current target, the market will be keen to hear what might come next.

With such clear divisions within the Governing Council, the risk is that the ECB are unable to convince the market that they have the tools to achieve their target or the willingness to continue using them.

The Inflation Target

There are three options for the inflation target: lower, higher or a flexible band. Lowering the inflation target is tantamount to accepting defeat and suggesting it is impossible to structurally raise inflation expectations – the resulting Euro strength would be too damaging.

An inflation band also seems unlikely due to the hawkish implications – if 1.5% to 2.5% is used for example, the market might conclude that the real target is the lower bound given the lack of desire to ease much further.

The more likely option is that they move to a 2% symmetrical target. However, unless this is followed up by action, will the market really believe the ECB can achieve it?

The Hawkish Risks

1) Highlighting the lack of credibility

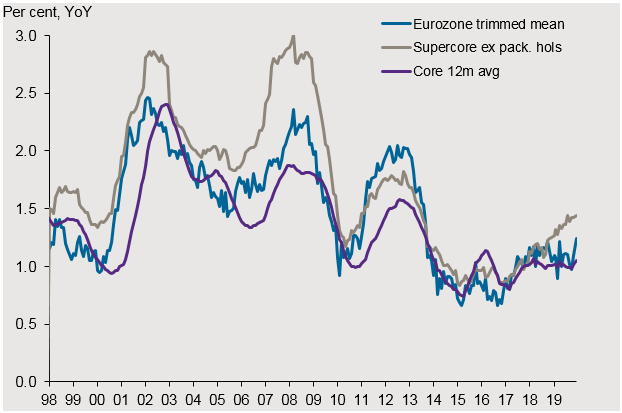

The ECB will likely conclude that their tools work well and just need some more time. They will point to rising inflation (Figure 1) and the progress since early 2017. They will argue that their tools are complementary and work well as package. Most importantly, they will be eager to convince the market that they can do more if they need to.

The problem here is that too many Governing Council members have openly criticised their own toolkit. Given Lagarde’s desire for consensus building, it seems the bar to ECB easing has risen significantly since Draghi’s leadership. Therefore, the first hawkish risk is that they increase their inflation target but take no action. This would only lend credence to the lack of tools narrative building in the market.

Figure 1: Measure of core inflation

Sources: ECB, Bloomberg, JPMAM as of 01/30/2020

2) Changing the inflation measure

The ECB may conclude that part of the reason inflation remains so low is due to measurement issues. The ECB could shift focus away from the volatile core HICP[1] (Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices) measure and towards other measures that have shown a more obvious upward trend in recent years (such as their Supercore measure above).

They could also attempt to include owner’s equivalent rent. In Europe, housing costs make up a tiny 6% of the consumer basket compared to close to 35% in the US. Whilst the data is currently not very reliable, if the ECB find a way to do this, it could boost the level of core HICP by ~0.2%pts.

All else equal, closing the inflation gap in this manner would have bearish implications for Eurozone rates.

3) Lack of consensus on negative rates

The ECB need to convince the market that rates can go more negative if necessary. But given the very public criticisms of negative rates from within the ECB, it may be difficult to do this.

Reading between the lines, it will become obvious that there is not really a consensus for rates to be pushed much more negative, without a large growth shock. The emphasis on the side effects of negative rates and the subsequent rhetoric around this policy tool will be closely watched.

What can the ECB realistically do to be dovish?

With such a limited toolkit the ECB have two potential dovish options.

The first is to change the parameters of the asset purchase programme. Increasing the issue/issuer limits seem more likely than changing the capital key but both are possible if the political hurdles can be overcome. The ECB could also provide a list of assets they would be willing to buy in the future. These could include non-financial equities and potentially even bank debt (to help offset the side effects of negative rates on bank earnings).

The other option is some form of forward guidance to convince the market that rates hikes are a long way off. An explicit inflation goal prior to hiking would help but would also tie the ECB’s hands for a long time. They could also extend more TLTROs (Targeted longer-term refinancing operations) as a signal that they are still easing, but this may be interpreted as having low confidence in their primary tools.

Telling the market that rate hikes are some way off may work but whilst there is an obvious dislike for cutting rates further within the ECB, the market may not react too much to these promises.

Better to keep quiet?

There are some difficult communication issues the ECB will be facing this year. In a similar vein to the Bank of Japan (BoJ), it may have made more sense to remain quiet and hope for reflation. A strategy review will only highlight the lack of tools and consensus within the ECB.

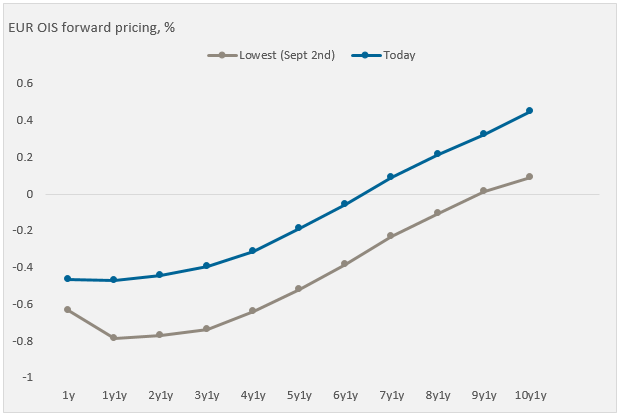

The aversion to cut rates further into negative territory has already changed the shape of the OIS curve in Europe (figure 2). At its trough, the market expected the ECB could get to -0.8% on the deposit rate. The question now is when to start pricing the upward slope.

Figure 2: EUR OIS Pricing

Source: Bloomberg, JPMAM as of 01/30/2020

Implications for markets

Either way, long dated Eurozone government bonds should benefit from this review. Whilst a hawkish interpretation could boost shorter dated yields, long terms bond yields would fall as the currency strengthens and inflation expectations decline.

Furthermore, if the ECB can pull off a dovish review, then long end bonds would surely benefit in the absence of significant fiscal thrust. Despite the ECB’s increasing pressure, this seems unlikely before a German election.

[1] In the euro area, consumer price inflation is measured by the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP). It measures the change over time in the prices of consumer goods and services acquired, used or paid for by euro area housholds.

The term “harmonised” denotes the fact that all the countries in the European Union follow the same methodology. This ensures that the data for one country can be compared with the data for another.