Emerging markets and the negative yield conundrum for fixed income investors

2019/10/17

Frederick Bourgoin

Zsolt Papp

The flipside of the 30-year bond market rally is that developed market bond yields have been decreasing to record low levels and more recently even into negative territory. This poses a major problem for fixed income investors, which in some cases is materially exacerbated by the high cost of hedging. In response, developed market investors have been increasingly diversifying into non-core assets such as emerging markets (EM) or high yield (HY). However, these asset classes are gradually also being affected by the “negative yield disease”. In view of this, we argue that one option for investors is to take active FX risk.

Significant problem for EUR and CHF-based investors

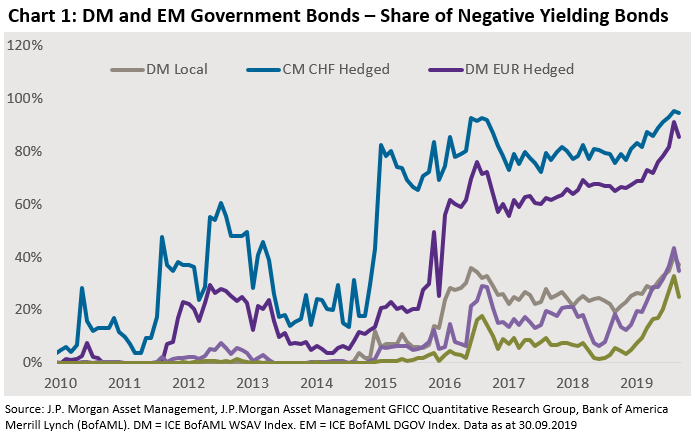

Chart 1 shows the share of negative yielding bonds in developed and emerging government bond markets, respectively. Importantly, we not only looked at bonds in their respective reference currencies, but also at yields hedged to Swiss Franc (CHF) and Euro (EUR). The picture is quite sobering, in particular for CHF-based investors. 94% of the developed government bond market universe is negative yielding when hedged to CHF. The situation is only marginally less dramatic for EUR-based investors. This is also not an entirely new phenomenon: in fact, it’s been a dominant market feature since 2015 for CHF and 2016 for EUR based investors.

Chart 1 also shows that EM is not immune. While there are no negative yielding bonds in the USD-denominated universe of EM government bonds, the share is already 25% hedged in EUR and 33% in CHF, respectively.

Dramatic impact on yield levels

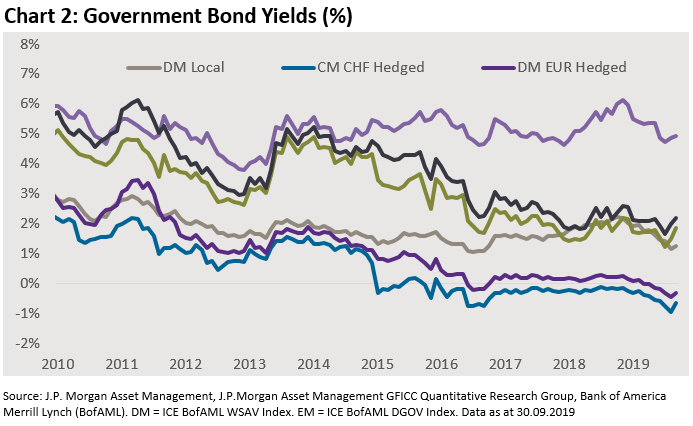

The impact on yield levels is dramatic for some investors. DM government bonds hedged in CHF offer a yield of -0.65%, which begs the question if “fixed loss” might not be a more appropriate term instead of “fixed income” for Swiss Franc-based investors. The outlook for EUR and JPY-based investors is only marginally less dramatic with hedged yields of -0.31% and -0.16%, respectively.

In contrast, EM (and HY) hedged yields remain comfortably in positive territory. It may not sound like much, but a CHF-hedged yield of 1.9% for EM government bonds looks very appealing when compared to -0.61%. Moreover so, as adding EM debt to a global bond portfolio does not necessarily mean adding more risk. Giles Bedford showed earlier in September (No Longer “Why” but “How”: The case for emerging markets debt matures, September 26, 2019) how the role of EM in fixed income portfolios is changing as it offers a higher Sharpe measure than the Bloomberg Global Aggregate.

In view of this, we would expect investors to increase diversification into non-core bond markets, especially as institutional allocation is still very low. According to Mercer, only 18% of European pension schemes have an average allocation of 5% to EM, which implies that there is ample room to increase exposure. Allocation to HY is equally very low.[1]

Unhedged vs hedged yield

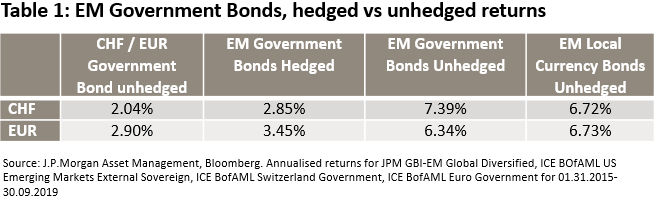

In addition to diversification, we believe that investors will also have to consider taking active currency risk in order to avoid the negative yield trap. First, unhedged yield levels are much more attractive, as clearly shown in Chart 2. Second, unhedged returns for EM government bonds have been significantly higher as hedging can wipe out as much as 60% of the return in some cases. Table 2 shows the performance of Swiss and Euro government bonds vs EM government bonds since entering the zero / negative yield spiral in early 2015. Third, this problem is likely to last and negative yields could even get more negative, as Jason Davis showed in his blog last week (Negative Rates – How low can you go? October 10, 2019).

In sum, there are several valid reasons why investors should consider taking active currency risk. One approach would be to invest in a traditional USD-denominated bond strategy, as illustrated by the ICE BofAML DGOV index, and hedge in the reference currency. Another approach would be to invest in EM local currency bonds, such as represented by the JPM GBI-EM Global Diversified index. Table 1 shows that this would have generated similar returns to USD-denominated bonds for EUR and CHF-based investors.

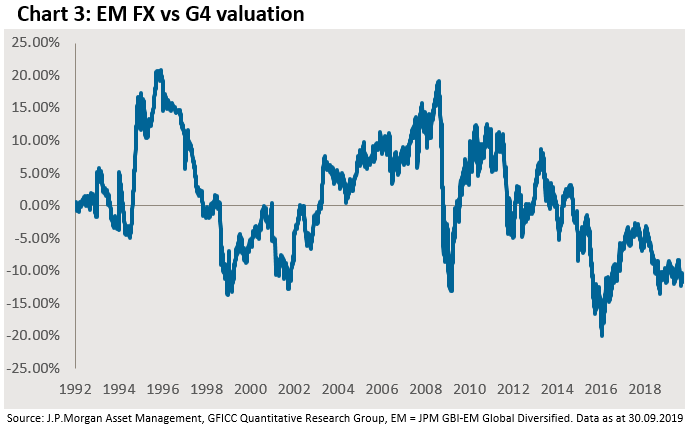

The latter leads to the question of whether it is a good moment to take active currency risk? We know from (sometimes painful) experience that in crises EM currencies can go lower and therefore valuation analysis has to be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, Chart 3 shows that EM FX is currently trading at long-time lows and not far off the historical low. This would therefore lend support to the view that current levels could offer an attractive point of entry.

So how do investors react to the idea of taking active currency risk? What we can observe is that strategies actively investing in local currency Rates and FX have seen significant inflows. Unconstrained bond funds attracted USD 57bn so far this year and EM local currency bond strategies (retail and institutional) USD 6.4bn. This is still below the amount going into EM hard currency strategies (USD 48.7bn) but it nevertheless illustrates that investors are prepared to take active currency exposure.

In sum, the growing share of negative yielding bonds requires investors to diversify away from core fixed income. EM bonds are offering a solution to this problem. However, as the high cost of hedging is eating into the income achieved in EM bonds, investors will also have to consider taking active currency risk in their portfolios. Flow of funds indicates that there is already some investor appetite, and as negative yields are likely here to stay (and potentially grow), we would expect demand for active currency solutions to increase.

[1] Mercer, European Asset Allocation Survey 2019