CLOs: not the CDOs of yore

2020/06/25

Sameer Riaz

The leveraged loan and CLO (Collateralized Loan Obligations) markets have grown in recent years. The amount of CLOs outstanding reaching USD 700 billion, up from USD 300 billion at the beginning of 2010. The leveraged loan market has increased from approximately USD 520 billion to approximately USD 1.2 trillion over the same time period. Along with this growth, the number of headlines predicting the emergence of the next crisis and comparison to subprime mortgages and Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs) of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC) have also increased. The focus of these articles has been on the weakening of loan underwriting standards, the complexity of securitized finance, and the impact of rising defaults on investors with regulatory constraints; one recent article even argues that bank holdings of senior CLOs could be impaired and lead to a crisis.

Real risks do exist to the CLO market – looser covenants, higher leverage, and the increase in loan-only structures can lead to quicker downgrades and higher losses upon defaults for the underlying loans. Credit selection, analysis of CLO manager performance, and understanding the nuances of the structure are key to investing in CLOs.

While acknowledging the risks, we believe that many of the comparisons to subprime CDOs are overly exaggerated, and that the rising credit risks in CLOs are well recognized by investors.

1. The CLO market is currently much smaller than the subprime mortgage market was in 2009, even before accounting for the growth of the U.S. economy and change in bank capital regimes. At the end of 2009, non-agency RMBS outstanding was north of USD 1.6 trillion, not including Home Equity Line of Credit Asset Backed Securities (HELOC ABS), which would only increase the total amount. The subprime mortgage market also had both synthetic derivatives and CDO squared structures, which would allow a single default to be felt many times over, exacerbating losses in the system. U.S. CLOs outstanding are USD 700 billion and have no comparable synthetic or CLO squared structures, limiting the extent of losses.

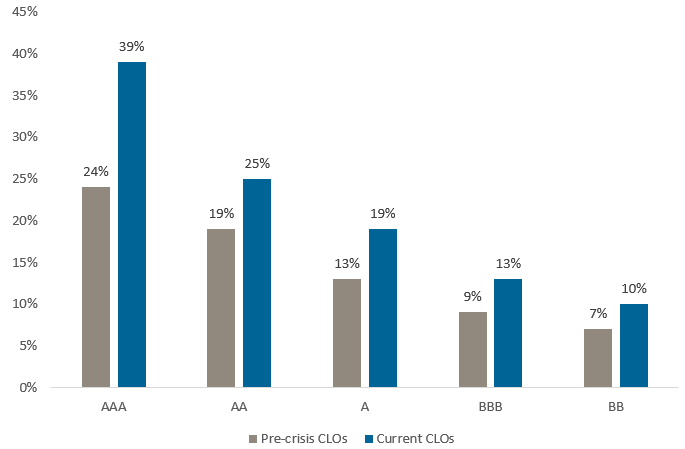

2. Compared to pre-2007 issuance, CLO debt tranches issued from 2011 on have increased credit enhancement (see Chart 1).

Chart 1: CLO Credit Enhancement has Evolved Over Time

Source: Citi, J.P. Morgan as of June 2020

Per Moody’s, no CLOs rated single A or higher have taken a loss since 1993 (a time period that includes the dot-com bubble bursting and the GFC). CLOs also have specific structural differences compared to other securitized products – as losses begin to impact CLO deals, the structure can divert cashflow from equity and lower-rated debt noteholders to pay down AAA tranches. This cashflow diversion acts to protect senior noteholders in adverse scenarios. In addition, CLOs have both industry and issuer concentration limits, among other tests and triggers.

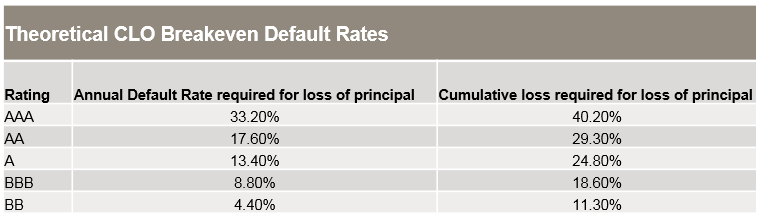

3. Default rates in the Great Depression peaked at 15.7% in 1933, while defaults during the Great Financial Crisis peaked at 12.1% in 2009. For a CLO AAA to lose principal, assuming a 50% recovery rate, annual default rates would have to exceed 33% for more than 2 years (see Chart 2), which would be more than double the highest rate seen since 1920.

Chart 2

Source: llustrative modeling assumptions from Intex as of June 2020; assumptions include 5% CPR, 50% severity upon default, and no reinvestment. Senior AAA shown.

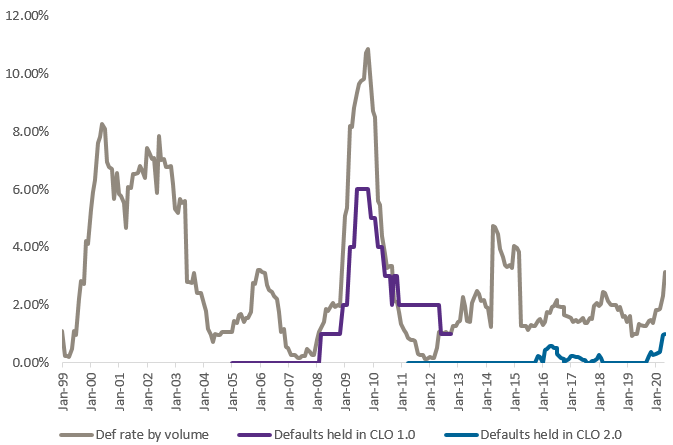

CLOs are also actively managed, and data over the last few years show that CLOs have experienced less defaults than the overall loan market (see Chart 3).

Chart 3: CLOs have held less defaults than the broader market rate

Source: Deutsche Bank, Moody's, S&P as May 2020

4. Subprime mortgages were primarily an “originate to distribute model”, while leveraged loans are syndicated to a broad investor base, with institutional investors such as insurance companies and money managers involved in the loan market along with CLOs. Investors have access to financial information and the ability to perform credit underwriting on a name by name basis. Market estimates suggest that over 60% of CLO equity was placed with managers in 2018 and 2019, highlighting the alignment of incentives in the post-crisis market that did not exist before 2009.

5. Loans are an important source of capital to US companies, providing financing to smaller issuers, as well as more common names such as T-Mobile, Delta, and PetSmart. The Federal Reserve recently set up the Main Street Lending Program, which provides access to lower rate financing to eligible companies. While we believe the program primarily serves as a backstop, the establishment of it serves as a signal of the importance of the loan market as a conduit for capital to US businesses.

Risks exist in both the CLO and loan markets – however, CLOs are a much smaller outstanding universe now than non-agency mortgages were in 2009, no derivative or CLO squared market exists to exacerbate potential losses, and the structure is designed to protect senior noteholders. To envision AAA CLOs taking principal impairments requires scenarios far worse than what we have seen since 1920, in a time of unprecedented fiscal and monetary action. While investing in CLOs does require deep credit and structural analysis, senior CLOs are built to withstand dire corporate default scenarios While comparisons between the pre-crisis subprime mortgage market and the CLOs of today are overdone, we have been focused on up-in-quality in our CLO investments, focusing on security selection in the light of increasing defaults and potential economic uncertainty.