Asian stocks will benefit from positive growth differentials relative to the U.S., while dividend stocks in Asia have robust fundamentals and are trading at attractive valuations.

In brief

- DM central banks are poised to keep rates “high for longer” to bring inflation back to target.

- In theory, the tightening in DM financial conditions may in turn imply a rise in Asian government bond yields.

- However, this relationship has decoupled since 2016, providing some buffer for Asian bonds.

- The partial passthrough and the end of the monetary policy tightening cycle in Asia present an opportunity to lock in higher rates.

- Should growth differential in Asia vis-à-vis the DM hold up, Asian growth and high dividend equities may turn attractive.

Central banks, the inflation dragon slayers

Since the expansive post-COVID reopening, central banks across the globe have been grappling with inflation underpinned by both pent-up demand and supply-side disruptions. We have witnessed arguably the most aggressive monetary policy tightening cycles since the Great Inflation of the 1970s, and it appears that markets are divided on whether we are at the conclusion of the current rate hiking cycle.

While inflation is moving in the right direction, continued hawkish central bank messaging has culminated in markets pricing in a prolonged “higher for longer" scenario for central banks, particularly for the U.S. Federal Reserve (the Fed). In the context of elevated inflationary price pressures, long-term U.S. government bond yields have increased sharply, which recently included higher term premia. The risk regarding the direction of where bond yields is contingent on the Fed's outlook in the near term.

Some buffer for Asian bond yields

In the past, Asian bond yields have typically moved in tandem with the U.S. bond yields. However, the relationship between the two has loosened over the years. The 12-months rolling correlation between the two has fallen from 0.91 at the end of 2021 to 0.52 in September. A potential reason for the loosening in the relationship is the relatively less aggressive monetary policy tightening cycle in Asia vis-à-vis other regions such as Latin America. Another factor is that Asia’s financial sector is increasingly intermediated through the banking system rather than the capital markets. All told, the decline in the sensitivity to U.S. rates has been positive for banks’ balance sheets more broadly. That being said, it is worth noting there is some variation among the Asian economies, with the largest passthrough in South Korea and the least in China.

The standouts: China and Japan

The narrative around bonds yields in China and Japan is a different story altogether. While most developed markets and Asian central banks have tightened financial conditions over the past year, a lackluster Chinese economy has prompted the People's Bank of China (PBOC) to stay in easing mode by reducing key interest rates as well as lowering bank's reserve requirement ratios. In Japan, while growth has been fairly resilient and inflation looks to have made a return after two decades of deflation, the Bank of Japan has maintained its accommodative stance on monetary policy by keeping short-term rates negative and retaining its yield curve control (YCC) policy, albeit with adjustments to YCC by allowing the 10-year Japanese government bond yields to rise up to 1%.

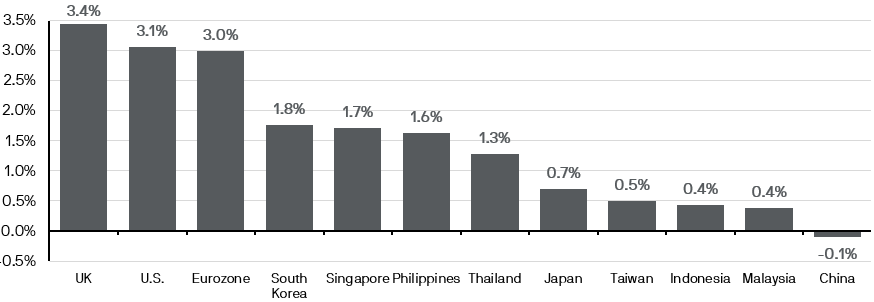

All in all, this has led to government bond yields in China and Japan to behave in contrast to the U.S. Treasury yields. While the U.S. 10-year Treasury yields have risen more than 333 basis points (bps) since the end of 2021, China's 10-year government bond yields have declined by more than 7bps, while 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yields have moved upwards in a restrained manner, rising 80 bps, pretty much moving in lockstep with the relaxation in YCC. Perhaps more importantly, the 10-year yield differentials for China and Japan relative to the U.S. have declined by more than 340 bps and 253 bps respectively, leading to the Chinese yuan and Japanese yen to decline more than 12.3% and 21.7% against the greenback (on real effective exchange rate basis) respectively since the end of 2021. For China, the sluggish growth momentum and less favorable rate differentials (from a historical perspective) have led to capital flight concerns. For Japan, the cost of hedging for local investors and positive JGB yields have incentivized Japanese investors to repatriate their investments back into Japan.

Exhibit 1: Change in 10-year government bond yields since 31/12/2021

Source: FactSet, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Data reflect most recently available as of 30/10/23.

What’s next for Asian bond yields?

Growth differential between the U.S. and Asia has been key to capital flows movements. With the U.S. growth resiliency expected to dial back slightly and Asian tech cycle likely to have bottomed, U.S.-Asia growth differential is likely to move in favor of Asia next year. Against the backdrop of U.S. policy rates staying “high for longer” as the Fed endeavors to meet its 2% target range, it appears that the decline in long-end U.S. bond yields could be gradual. On the flip side, should the 10Y government bond yields edge closer to the 5% handle again, the lack of full passthrough from U.S. to Asian bond yields could provide somewhat of a price buffer.

Meanwhile, the U.S. dollar is likely to remain resilient in the near-term, particularly in the context of the heightened geopolitical risk and weaker growth prospects for the Eurozone. Thus, Asian currencies could see further weakening pressure in the coming months. While Asian central banks are likely done with their hiking cycle, they will not be in a hurry to cut policy rates given their concerns over FX weakness – as exemplified by the recent trend of FX market intervention. This coupled with the broadening in disinflationary pressures in the region, should mean that Asian bond yields are capped in the near term.

Investment Implications

Given the expected weakness in Asia FX, refinancing concerns and relatively unattractive interest rate differential vs. the U.S., the opportunities within the Asia fixed income space will involve a high level of selectivity and a quality bias. On the other hand, the current macroeconomic conditions warrants a look into high dividend stocks in Asia. Asian stocks will benefit from positive growth differentials relative to the U.S., while dividend stocks in Asia have robust fundamentals and are trading at attractive valuations. As cash rates move lower in the longer run, Asia dividend stocks will also provide a stable income source.