Assets that can deliver stable long-term returns while also generating income and offering protection from inflation are hard to find in traditional equity and bond markets. Investors have instead turned to real assets, such as real estate, infrastructure and transportation, as sources of long-term stable returns that are positively correlated with inflation.

An equally valuable but much less commonly used real asset strategy is timber investment – growing and harvesting trees for construction and other uses. While the basic investment case for timber goes back to antiquity, this ancient resource is now gaining attention for a decidedly modern purpose: the sequestration of atmospheric carbon.

In this article we explore the strategic case for timber in an asset allocation, taking a closer look at how timber investing delivers attractive risk-adjusted returns through traditional channels and how the more recent focus on sustainability may add a new element to the value proposition.

The strategic case for timber in portfolios

Core real assets, broadly defined, are long-lived physical assets with stable cash flows and a positive sensitivity to changes in inflation. In many cases, such as real estate or transportation, these revenue streams are generated through leases that periodically reset across time. In other instances, such as power generation and distribution, the asset owners operate under long-term contracts that pass through costs to end users. Timber operates somewhat differently, while preserving the key benefits. Forests produce trees that are harvested when mature, yielding logs that are cut in sawmills to produce lumber for construction. This process delivers returns that correlate strongly with housing demand, growth and ultimately inflation.

Unlike low-returning inflation-sensitive assets, such as inflation-linked bonds and commodities, core real assets have the potential to generate higher returns over a long horizon. Timber, in particular, offers the ability to respond opportunistically to changes in prevailing prices.

While the trees themselves increase in value slowly as they mature, the decision as to when and how much to harvest can reflect the prevailing prices for logs and wood. Conceptually, this is somewhat similar to owning an oil field and having discretion to pump more or less oil as prices change – except that timber (the oil field in this analogy) grows more valuable with each passing year.

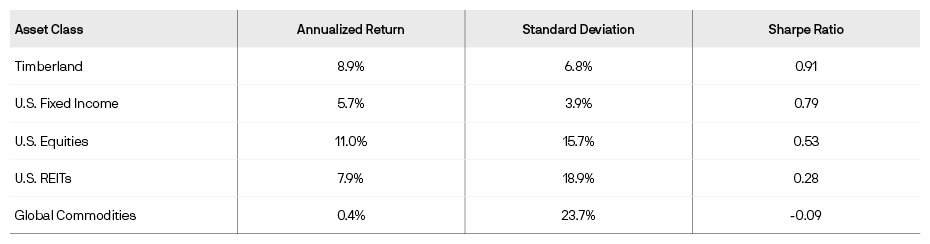

Historical returns and risk characteristics (Exhibit 1) offer a compelling argument for timber as a strategic asset allocation. But the case for moderate returns with low volatility runs deeper than just a Sharpe ratio, and may be even stronger than many investors realize. Why? Because these assets do not require the additional ballast of low-returning fixed income elsewhere in the portfolio to offset price risk. With inflation elevated and rates likely to rise, the cost of holding fixed income for risk reduction purposes is quite high.

Timberland can generate higher returns with lower volatility

Exhibit 1: Timberland returns vs. public markets, 1991-2021

Source: Bloomberg, NCREIF, JPMAM. Data as of September 30, 2021. Indexes: S&P 500, NCREIF Timberland Index, NA REIT Index, BB US Aggregate Bond Index and S&P GSCI Commodity Index.

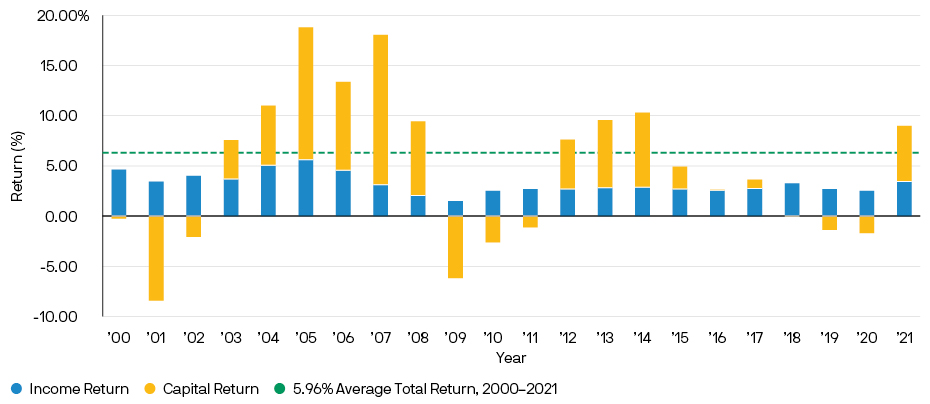

Income serves to offset illiquidity

Asset allocation often requires a balancing act between return and risk, and between income and illiquidity. Core real assets offer attractive risk adjusted returns, but also relatively low levels of liquidity given slow transactions and long investment time horizons to realize value. This is particularly true for timber, as trees grow slowly and only reach their maximum value after decades in the ground. While investors generally prefer more liquidity than less, in the current environment liquid assets tend to offer lower returns. And while other illiquid alternatives can offer higher absolute returns, they generally offer little or no income over time. Income offers flexibility in any environment, but it is particularly valuable in a period of inflation and rising interest rates. As a result, timber (and the broader core real asset sector) fills a valuable middle ground that many portfolios are lacking (Exhibit 2).

Timberland produces steady income across time

Exhibit 2: Timberland performance broken out by income and capital return

Source: NCREIF U.S. Timberland Property Index (year-end total return). Data as of December 31, 2021.

A renewable resource for generating returns

Investors can gain exposure to timber in several ways: directly owning and harvesting forest land (not common given the highly specialized skills required); owning shares in timber REITs (public paper, packaging and wood product companies) that own forest land along with the “downstream” sawmill and distribution businesses; or through a private fund specializing in forest management and timber harvesting. We will focus on this last option, which is the most practical “pure play” for investors seeking exposure to the asset class.

Forest management has come a long way from the era of clear-cutting and log jams. A modern, managed forest leads to higher levels of biological growth and minimizes the risks from fires and pests. Drone and satellite technology is being used to survey, assess and protect existing forests with unprecedented accuracy, while more efficient harvesting across geographies and species allows well-capitalized and globally diversified timber companies to get trees to market faster than ever before.

Old vs. modern timber harvesting

Positive fundamentals for demand

Despite the technological sophistication of modern forestry, the main challenge for timber managers remains the uncertainty of future demand for cut wood. Residential housing markets drive a significant portion of demand, either through construction or renovation, and can be subject to cyclical volatility. Ideally, there should be a natural ebb and flow between rising housing demand and higher wood prices, which is in turn met by increased harvesting of mature trees and a subsequent decline in prices. In the event of a decline in demand, trees can be left standing, but allowing too many mature trees to remain uncut until demand rises may ultimately depress prices over a longer horizon.

The current macroeconomic backdrop may create favorable dynamics for timber prices over the medium term. The U.S. housing sector was underbuilt over the last decade, resulting in low supply and significant pent-up housing demand. In addition, low interest rates and the long-anticipated emergence of housing and remodeling demand from millennials should support housing expansion for the next three to five years or longer. Lastly, wood-based construction is increasingly viewed as a safer, more accessible and sustainable alternative to steel and concrete. Engineered wood product innovations like cross-laminated timber (CLT) in medium-rise construction projects may increase long-term demand for timber.

The value of carbon capture

As our economy moves in the direction of greater sustainability, the value proposition for timber may evolve well beyond its use in construction. As noted earlier, trees increase in value as they mature. This value is no longer simply because their wood is closer to being harvested, but also because trees offer a powerful tool in the fight against global warming. Forests offer one of the most effective and scalable mechanisms for sequestering atmospheric carbon at a time when many businesses are looking to achieve low or even net-zero carbon emissions from their operations. The emerging business of carbon offsets allows companies that produce carbon to neutralize a portion of their output by paying timber growers to not harvest their trees.

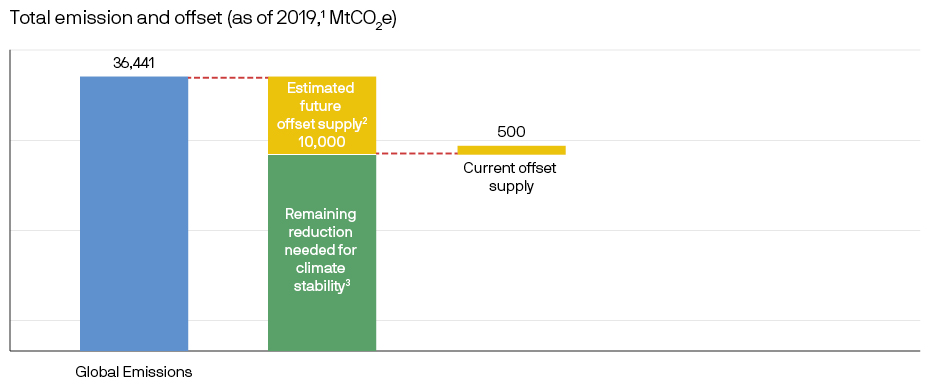

The size of the challenge, and the opportunity, is described in Exhibit 3 below. The total annual level of global carbon emissions, currently above 36,000 metric tons, will need to decline by approximately 10,000 metric tons to keep global temperatures within 1.5 degrees centigrade through the year 2100. Limiting output is possible, but difficult. Direct offsets through carbon sequestration can meaningfully reduce the total while giving the global economy time to adjust to a more sustainable model.

The question, of course, is where will the offsets come from? Forestry, at present, represents approximately 40% of the current supply of offsets. That percentage is likely to grow over time.

The scale of carbon emissions vastly exceeds the current supply of offsets

Exhibit 3: Global carbon emissions and offsets

Source: Source: Global Carbon Atlas (http://www.globalcarbonatlas.org/en/CO2-emissions); Carbon Registries (total of carbon offset registered on Climate Action Reserve, American Carbon Registry, Carbon Plan, Gold Standard, Verra, Clean Development Mechanism); ARB is not included since projects are also registered in American Carbon Registry, Climate Action Reserve, and Verra. 1Data as of 2019 - unless unavailable (Carbon Plan as of 2021 and Verra as of latest yearly data). 2Annual carbon reduction needed to achieve the Paris Agreement goal of 1.5oC temperature reduction by 2100.

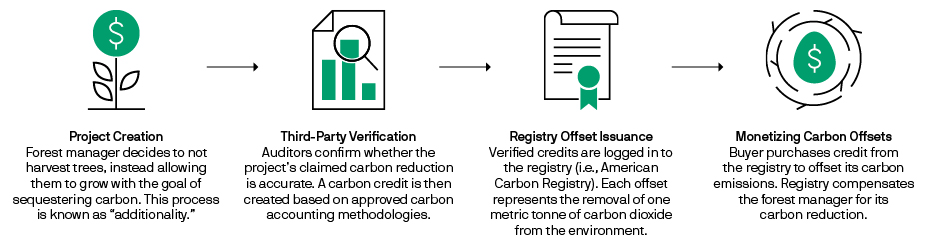

While the carbon offset market is still young, the process by which carbon offset credits are created, verified, registered and sold is becoming increasingly institutionalized (Exhibit 4). Further, there are a number of promising technologies focused on measuring, harvesting and locating buyers that could increase supply and broaden the market to include small and mid-size landholders. For the time being, however, the demand for offsets from corporations exceeds the supply leaving timber owners in an advantageous position.1

The carbon offset process is becoming increasingly institutionalized

Exhibit 4: Carbon offset creation process

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Updating the economics of timber investing

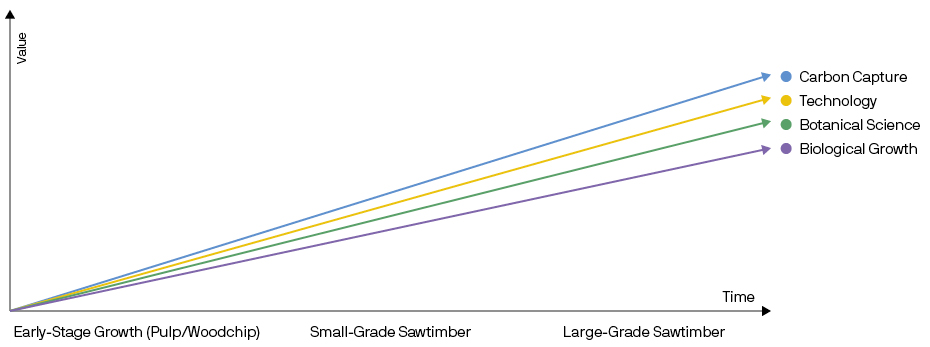

For timber investors, the ability to generate income from trees while they grow is transformational: put simply, rather than waiting to get paid, they can now get paid to wait. As Exhibit 5 illustrates, each layer of modern forestry management increases the value of timber. The unique benefit of carbon offset revenue, however, is that it does not require the tree to be felled in order to realize returns. Over time, this should keep more trees in the ground, benefitting the environment yet also reducing the overall timber supply (all else equal), and thereby supporting overall prices for cut wood. The returns available to large forestry companies that can optimize the mix of revenue from harvesting trees and selling carbon offsets may be substantial.

Modern forest management maximizes the return potential of timber investing

Exhibit 5: Value added by forest management

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Amid volatile markets, the capacity of timber to deliver steady returns with low volatility can improve portfolio efficiency while offering resiliency in the face of inflation and rising rates. Looking ahead, we can add the sustainability benefits from carbon sequestration and the associated income stream from the sale of offsets. As a metaphor for investment, the slow and steady growth of a sapling to a tree is obvious. As an actual investment, timber offers more than just patient growth.

1 Russell 3000 companies, for example, produce over 7,000 metric tons of carbon, far exceeding the current 500 ton offset supply.

4450d980-8f8e-11ec-92fc-eeee0af74317