The global supply chain mess will require increased global vaccination and acquired immunity, semiconductor capacity expansion and the end of extraordinary housing/labor supports to resolve. We expect all three to occur over the next few months, leading to a global growth bounce in 2022

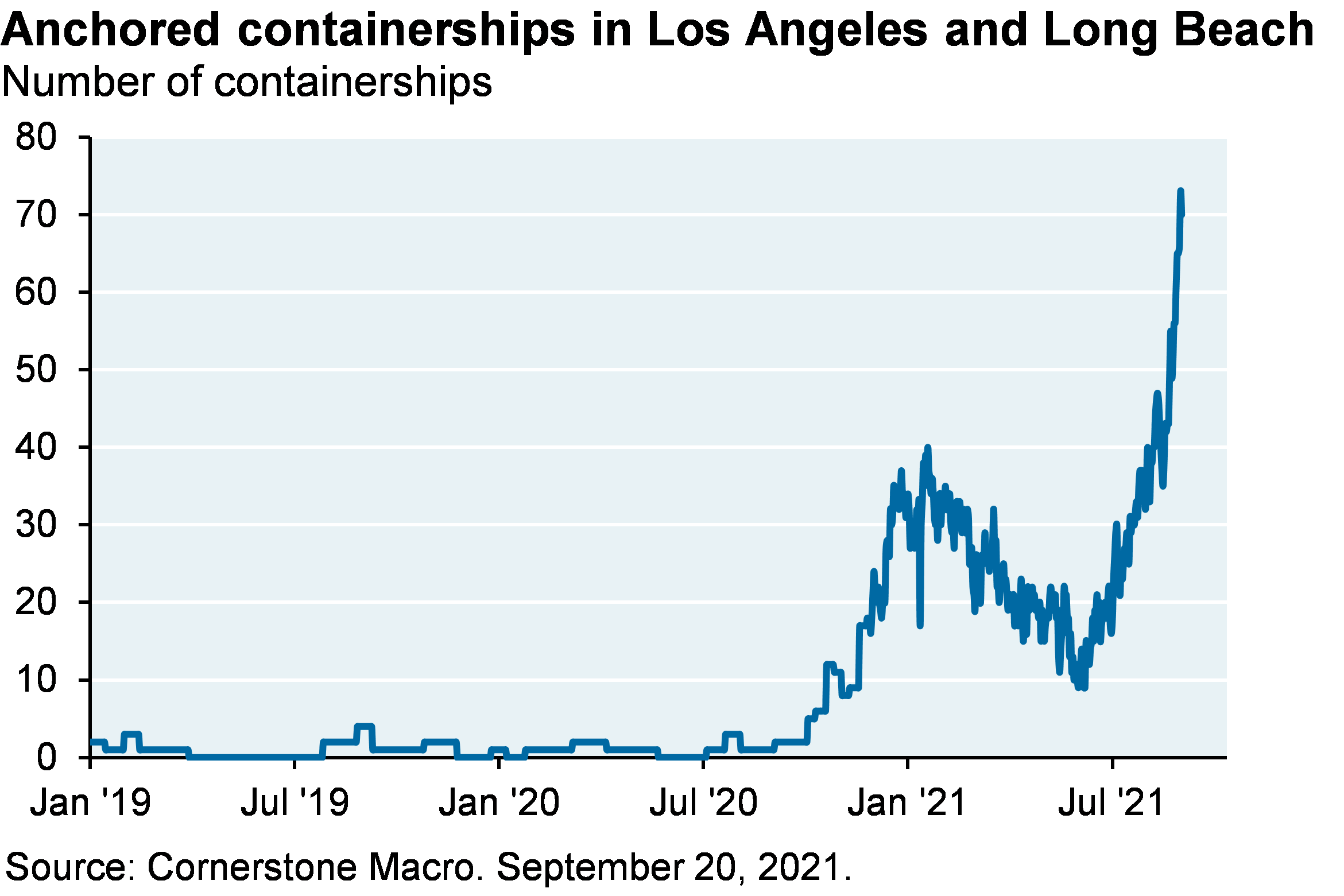

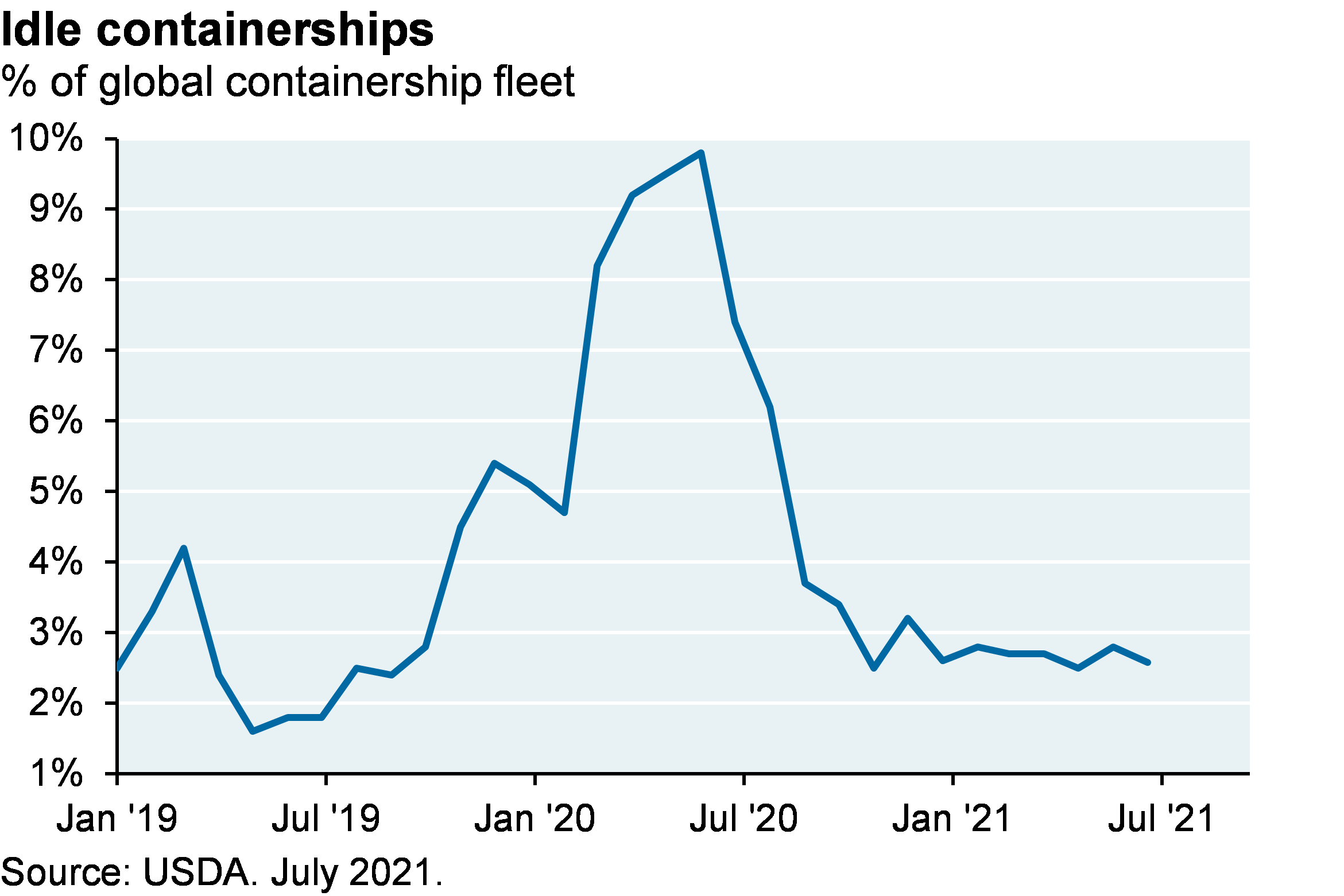

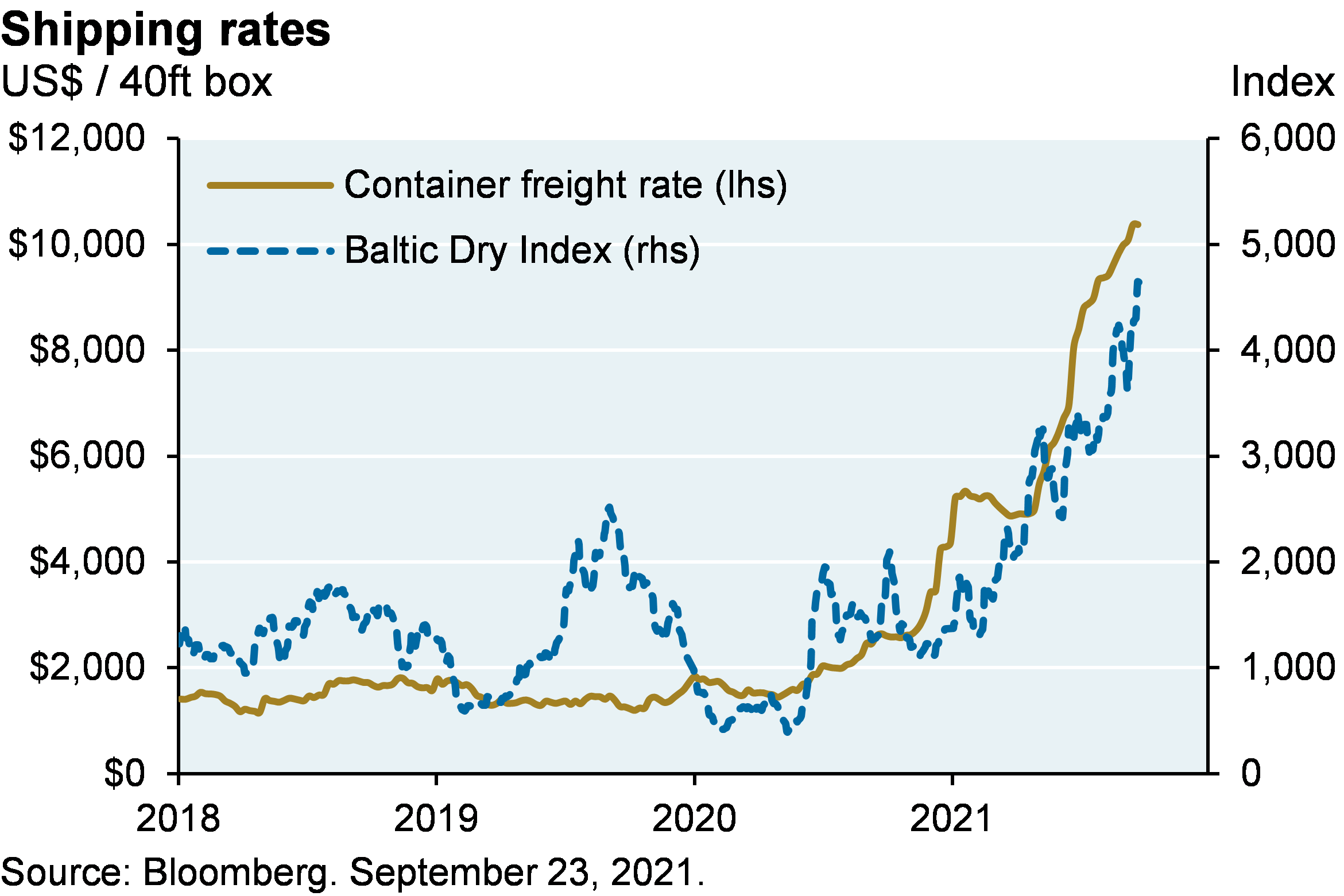

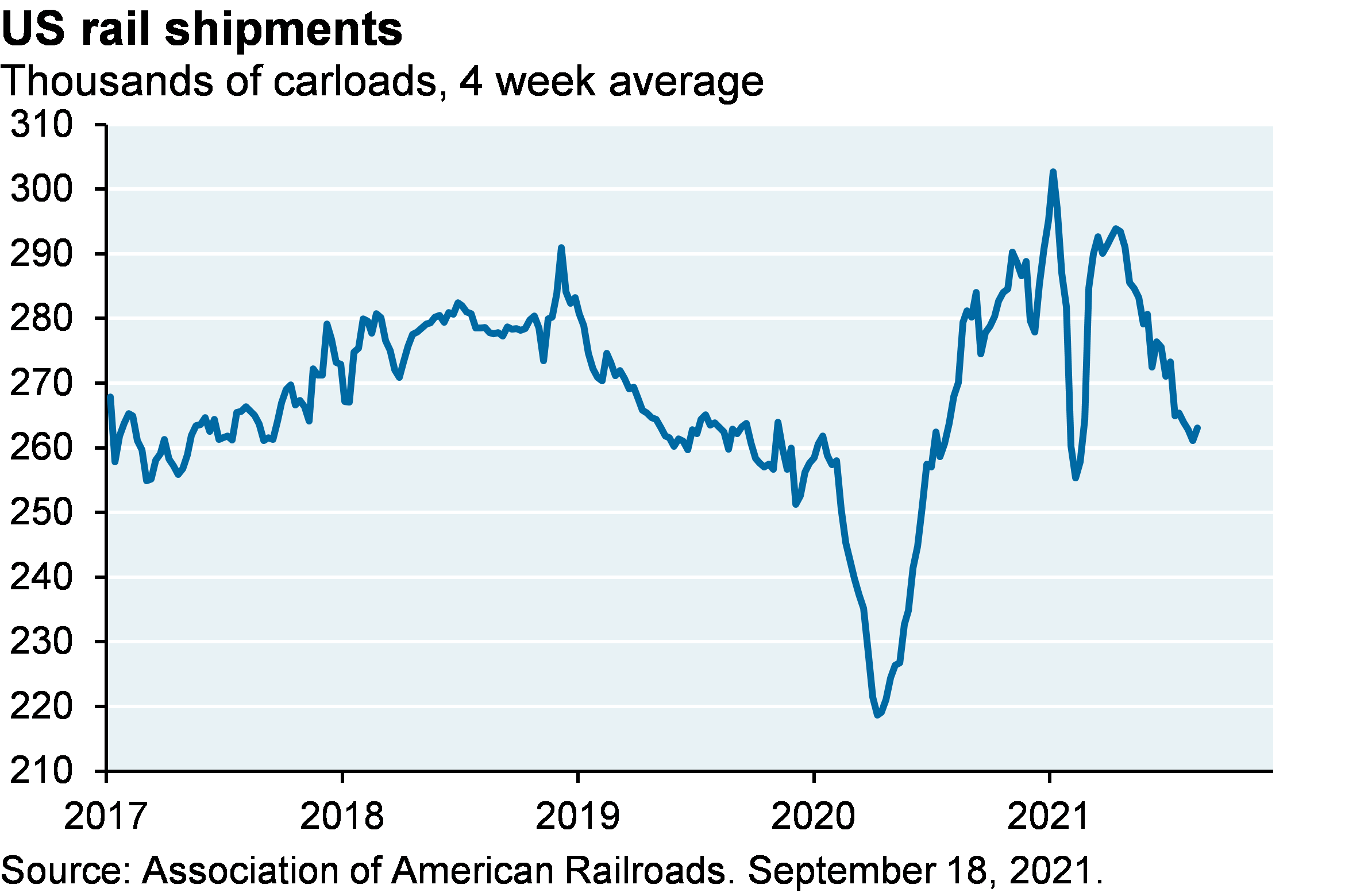

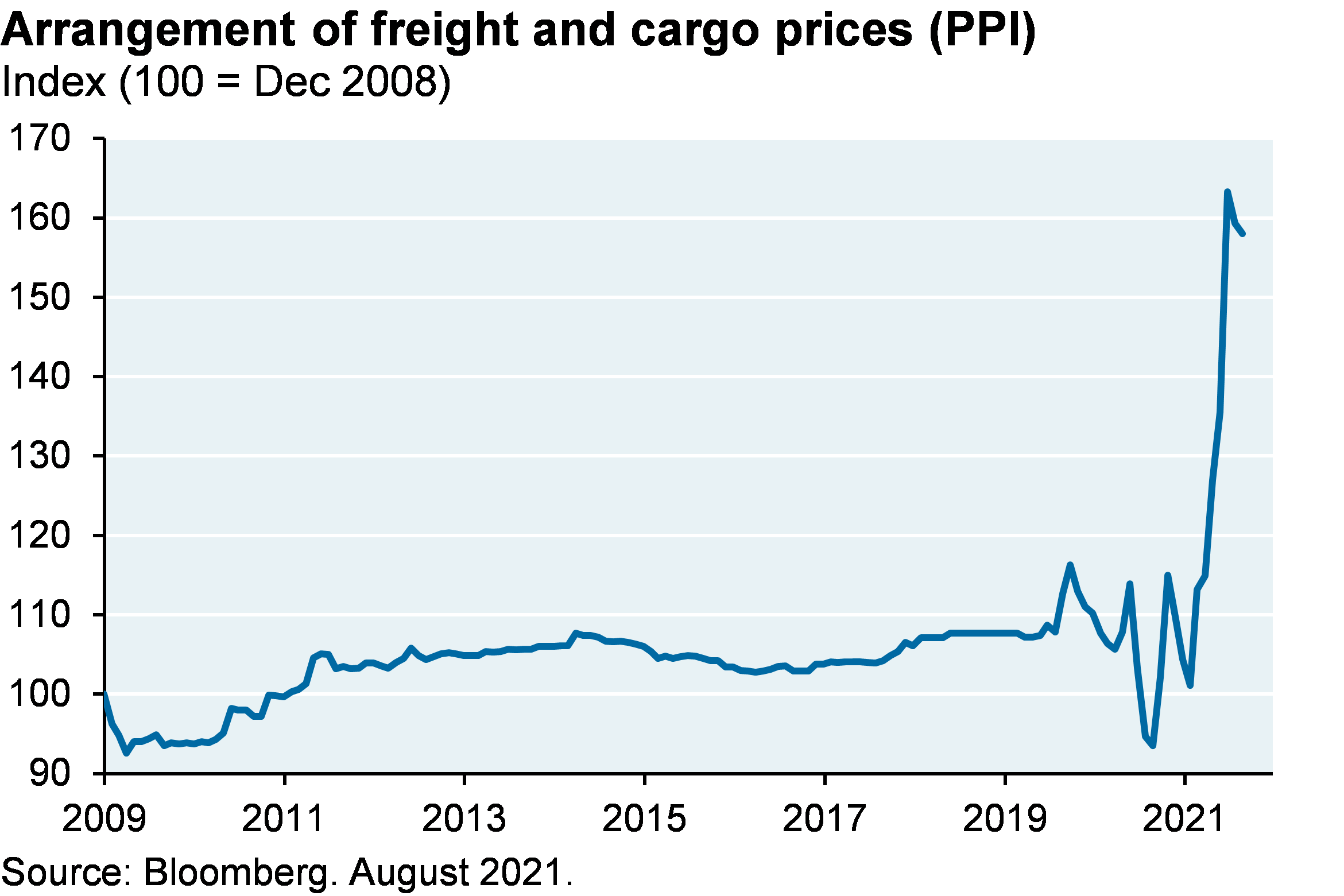

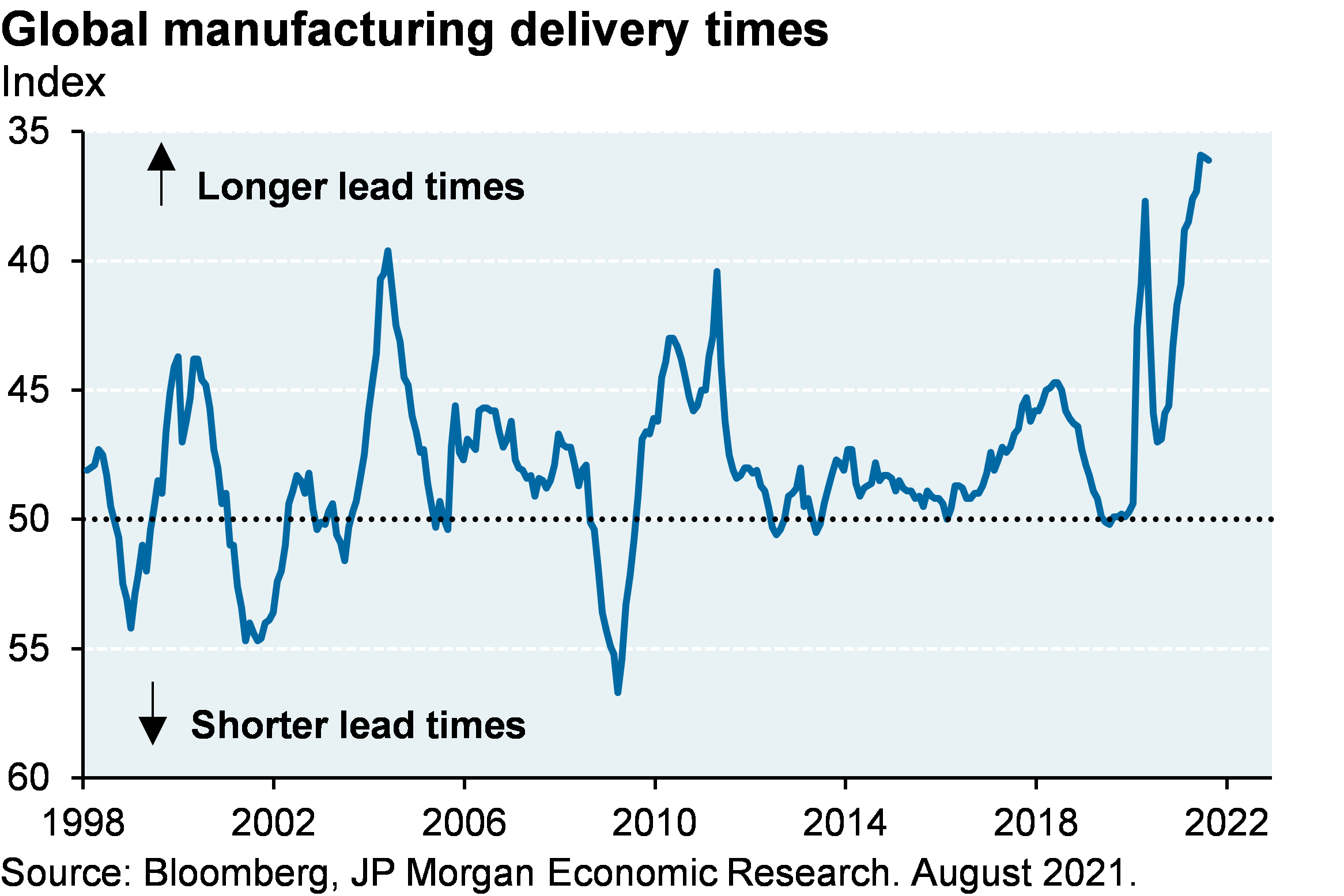

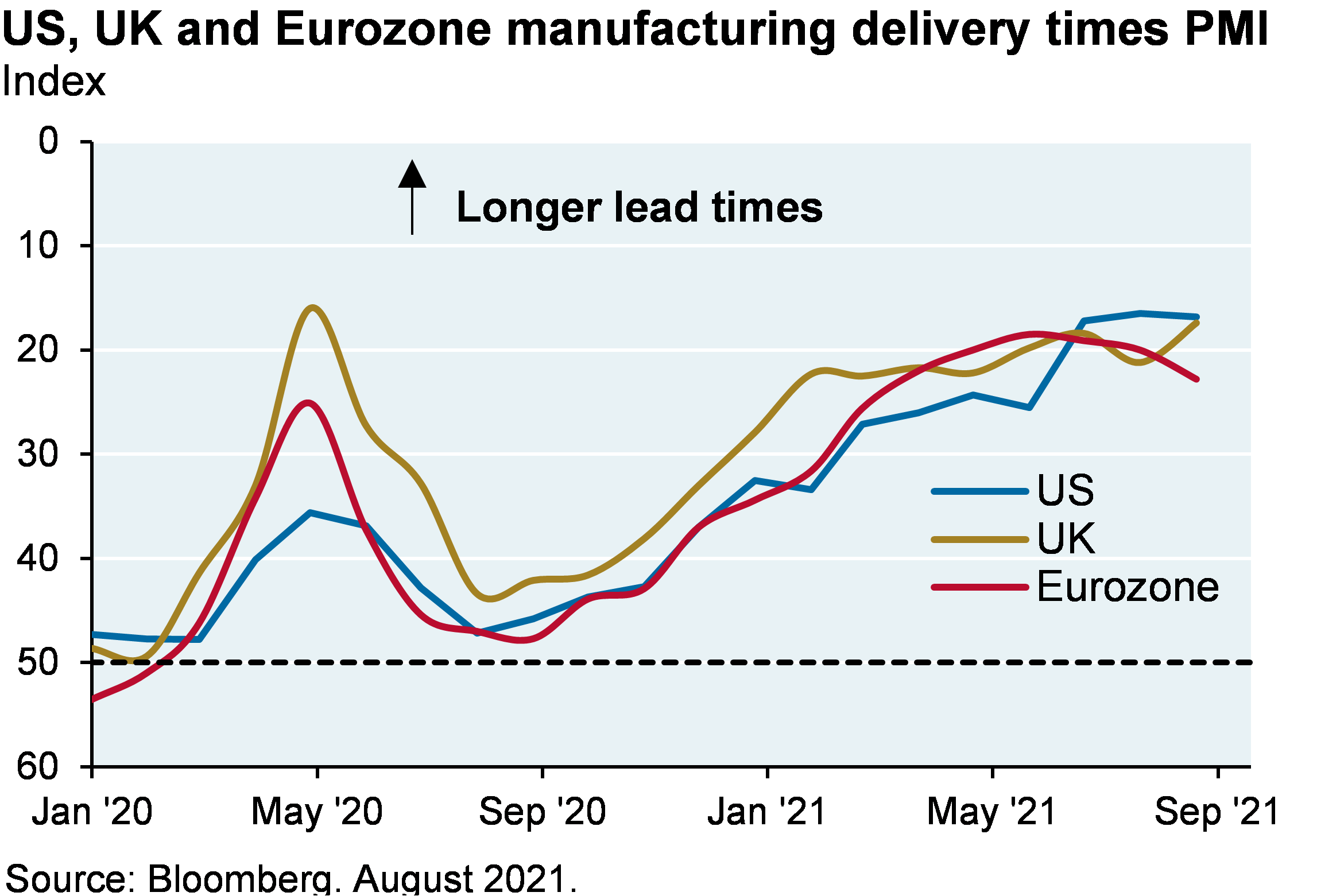

The containership industry is a good illustration of the supply chain mess: as shown in the first chart, more than 70 containerships are stacked up outside Los Angeles/Long Beach ports waiting to unload. Idle containerships are back to just 3% of the total fleet, shipping costs are surging, manufacturing delivery times are extended and rail shipments are declining sharply from their summer peak, illustrating the far reaching impact of the delays.

Why so many bottlenecks? Supply chain disruptions due to shipping cost discrepancies

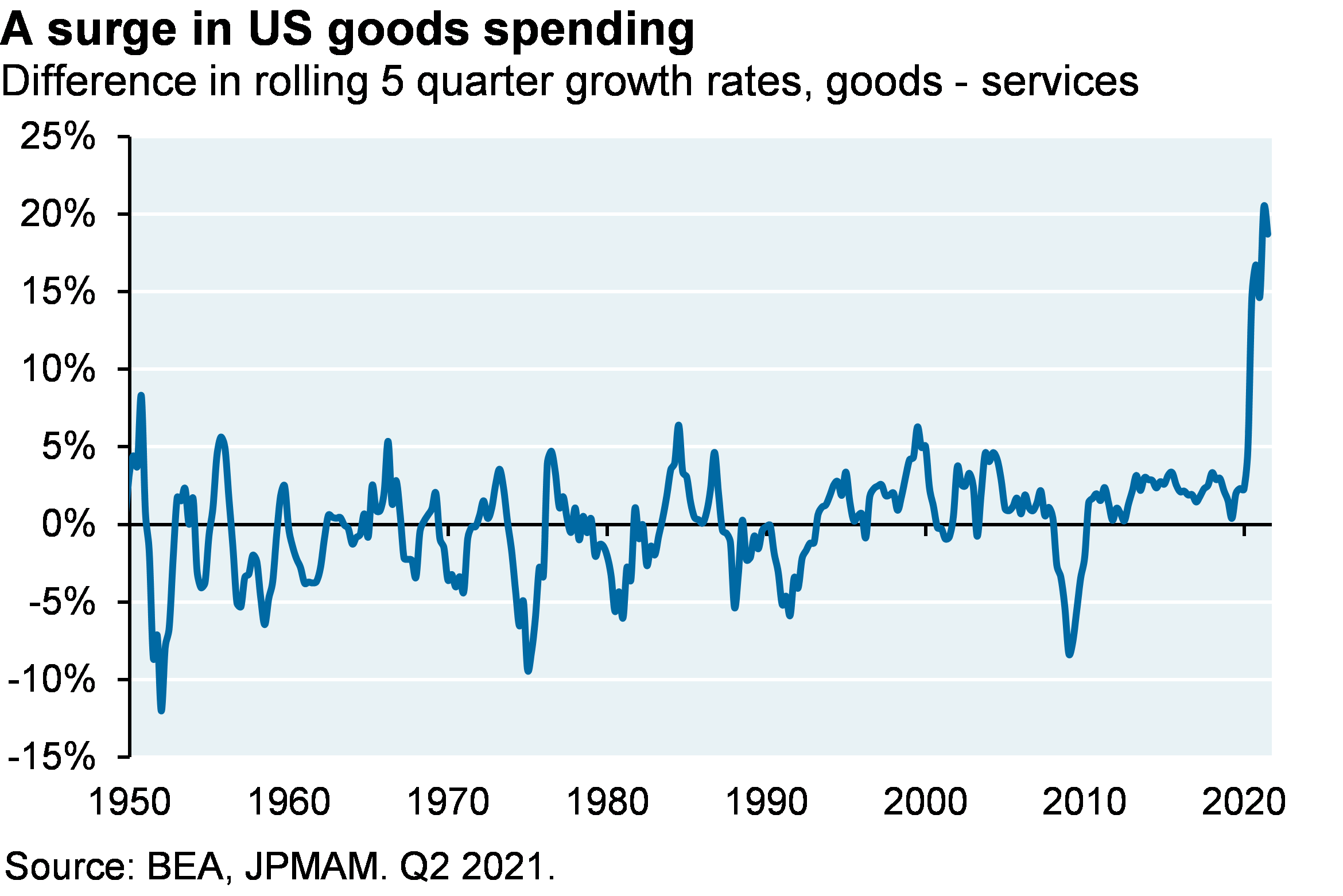

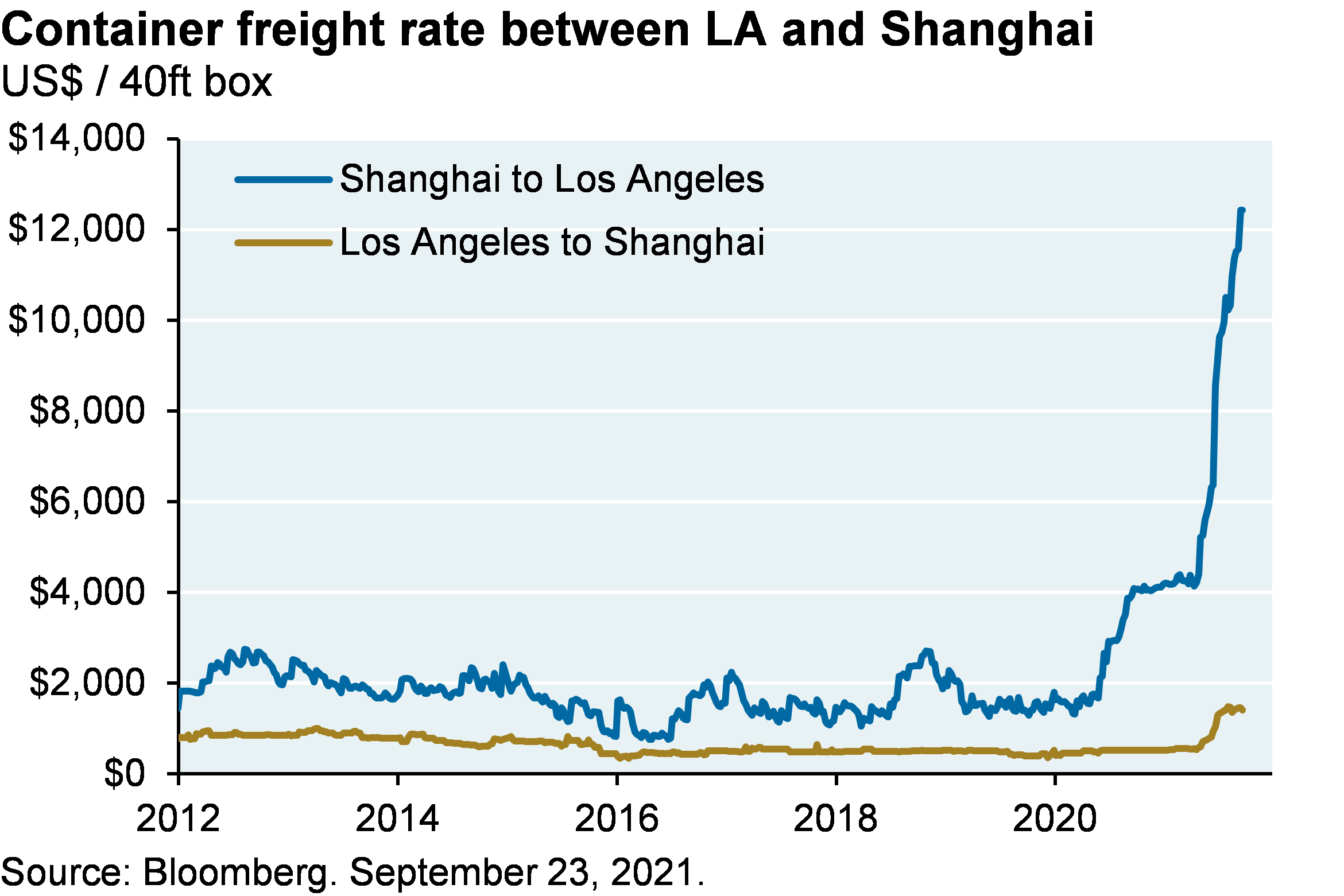

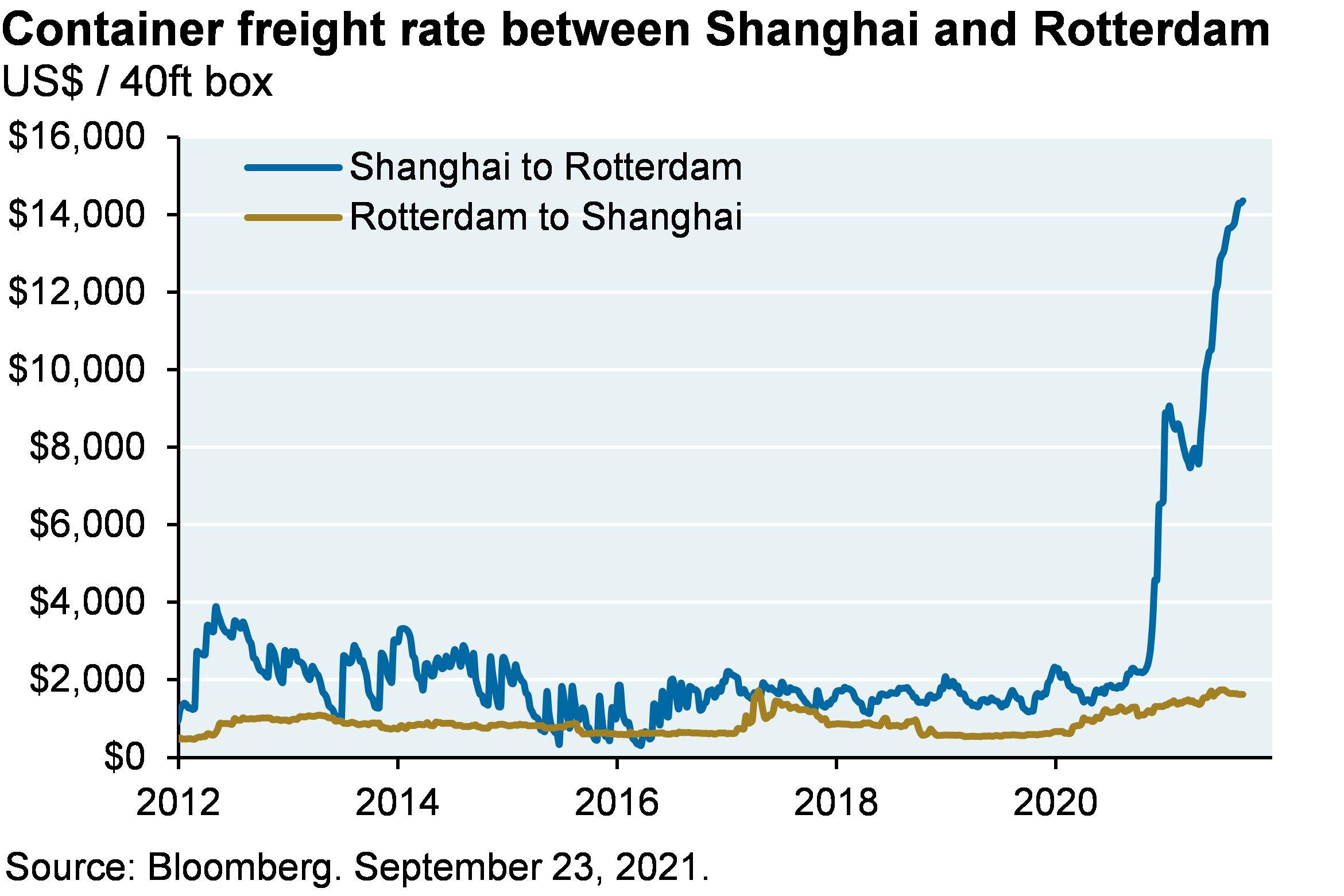

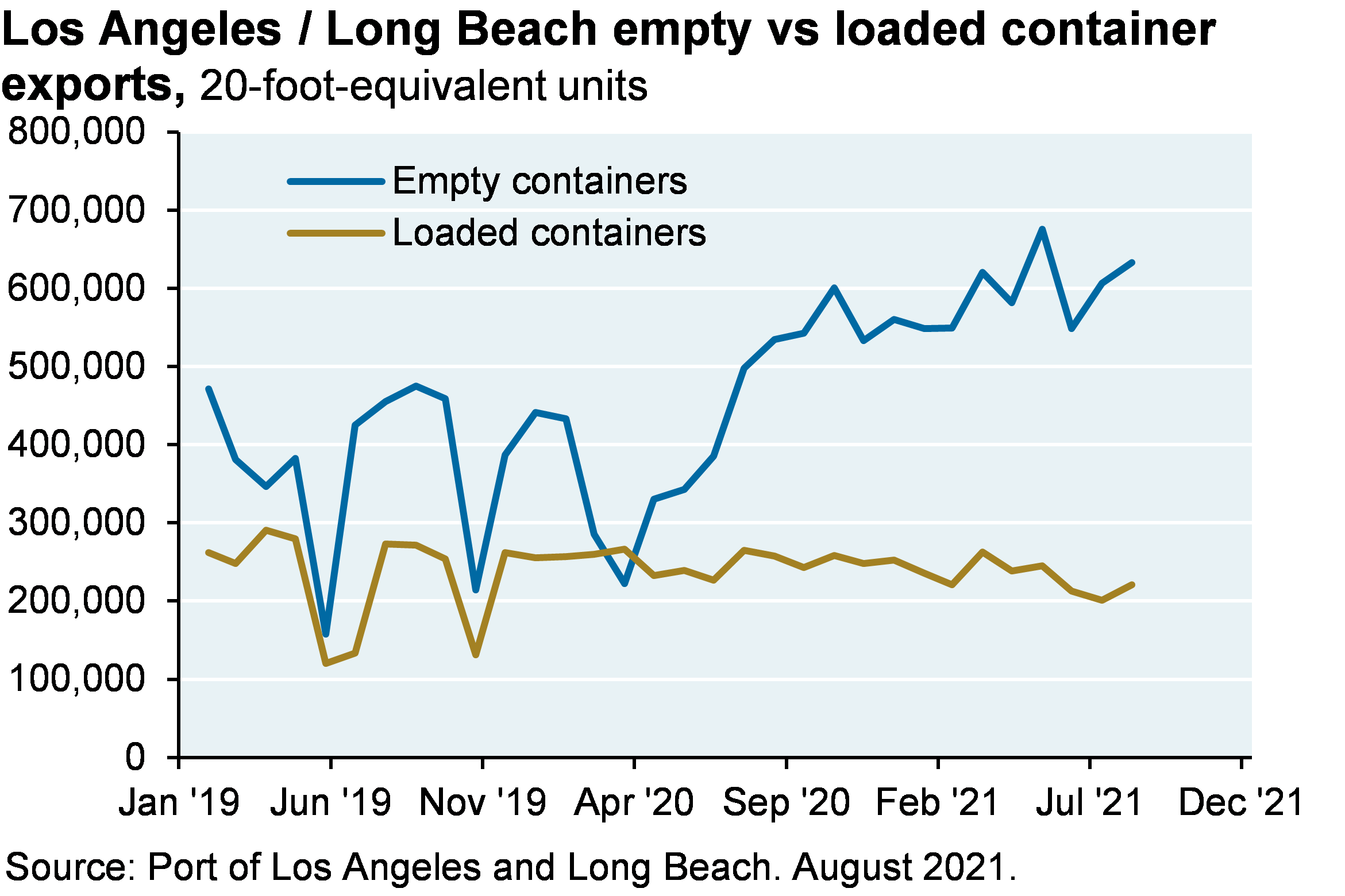

COVID has disrupted supply chains in two major ways: surging demand for imported consumer goods in the West due to pandemic work from home trends and other home improvement spending, and a decline in workers required to maintain and operate these supply chains. The surge in US import demand has led to a sharp rise in eastbound freight rates (see charts for Shanghai->LA and Shanghai->Rotterdam). However, westbound freight rates have not risen nearly as much, leading to an odd and problematic phenomenon: incentives for container owners to move them back to China empty to accelerate receipt of eastbound freight rates, instead of waiting for containers to be refilled to earn westbound freight rates as well. This is illustrated in the fourth chart which shows departing containers from LA/LB: a lot of them started leaving empty once eastbound freight rates surged. This further exacerbates supply chain issues, since US goods (i.e., grains) that were supposed to depart US railcars and warehouses for export remain in place, occupying space that US imported goods were destined for.

The other big bottleneck: the semiconductor shortage

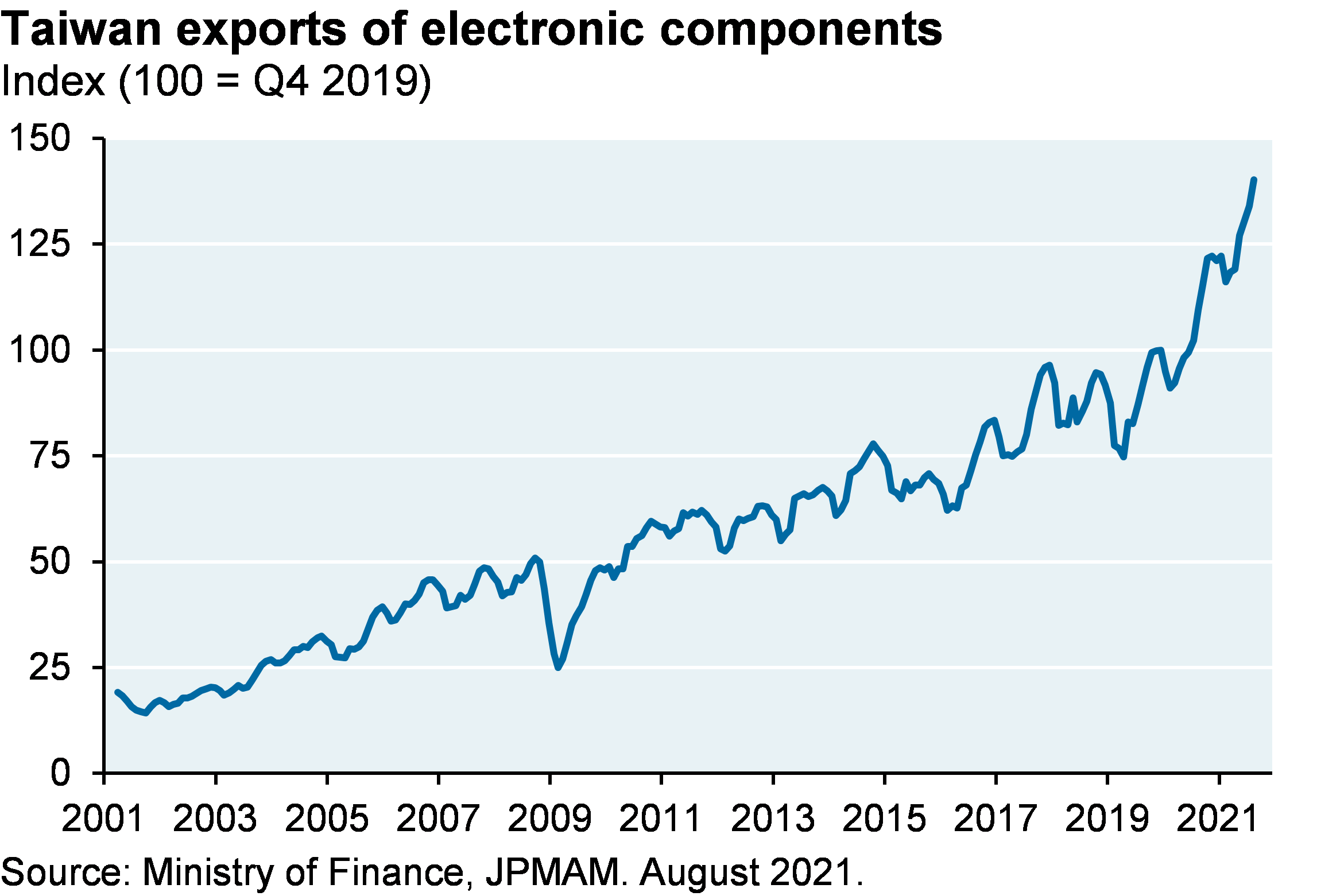

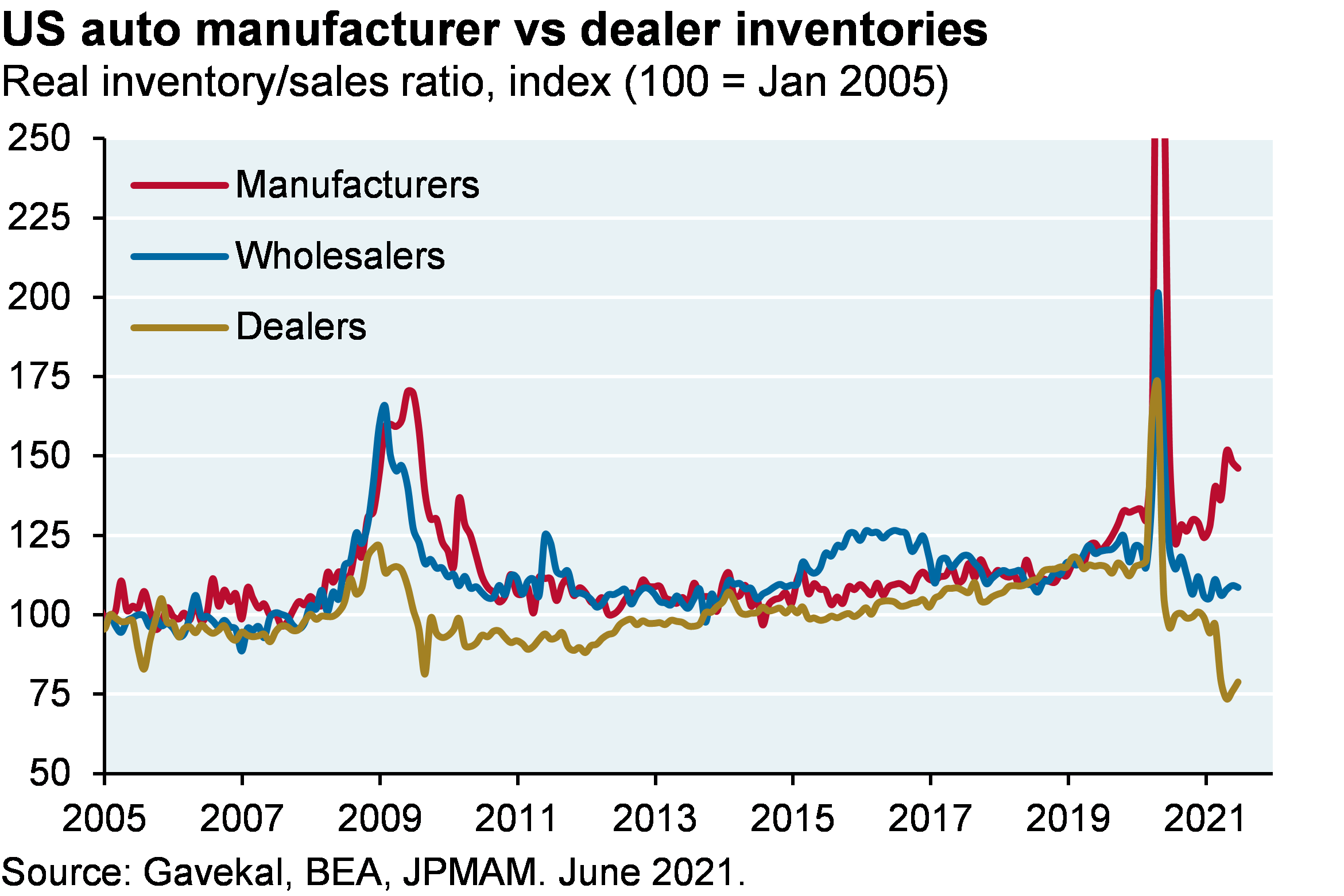

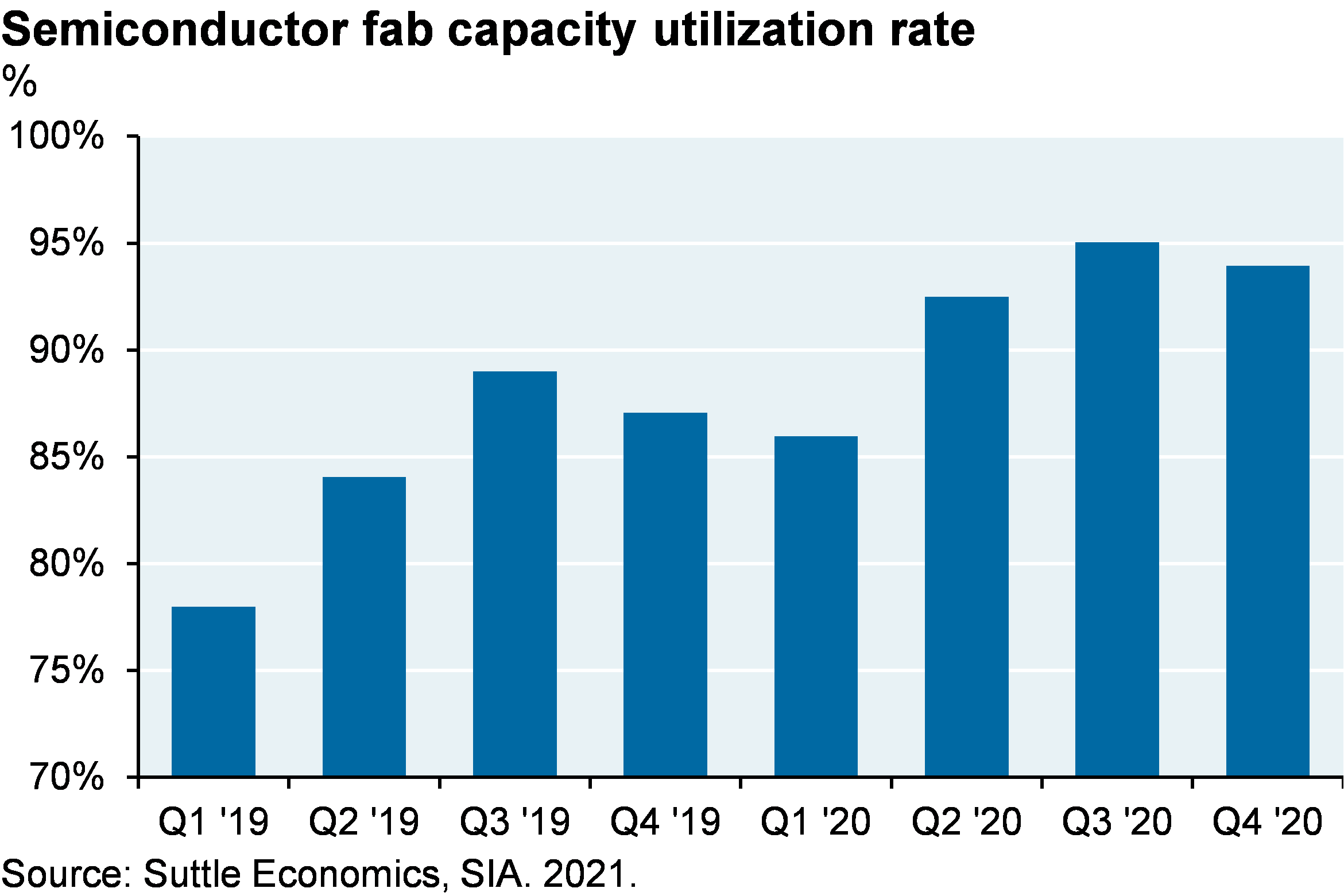

Semiconductors are the world’s 4th most traded good after crude oil, refined oil and cars. Strong demand existed before COVID and reflected the chip-intensity of 5G, AI, electric vehicles (3-5x the chip content of ICE cars) and the internet of things. Current chip shortages are mostly related to older and simpler 200-mm silicon wafers used in cars, computers, monitors, laptops, TVs, refrigerators and washing machines. Demand for many of these items soared during the pandemic as people built out home offices and related projects; this surge in demand is illustrated below via the rise in Taiwanese electronic component exports. One by-product of the shortage: a rise in US auto manufacturer inventories and a collapse in dealer inventories as manufacturers wait for the chips they need. Auto consulting firm Alix now estimates that the semiconductor shortage will cost US auto manufacturers $210 bn this year, up from their $60 bn estimate back in January. Ford is actually offering customers faster delivery if they agree to “lower feature content”, which translates into fewer semiconductors.

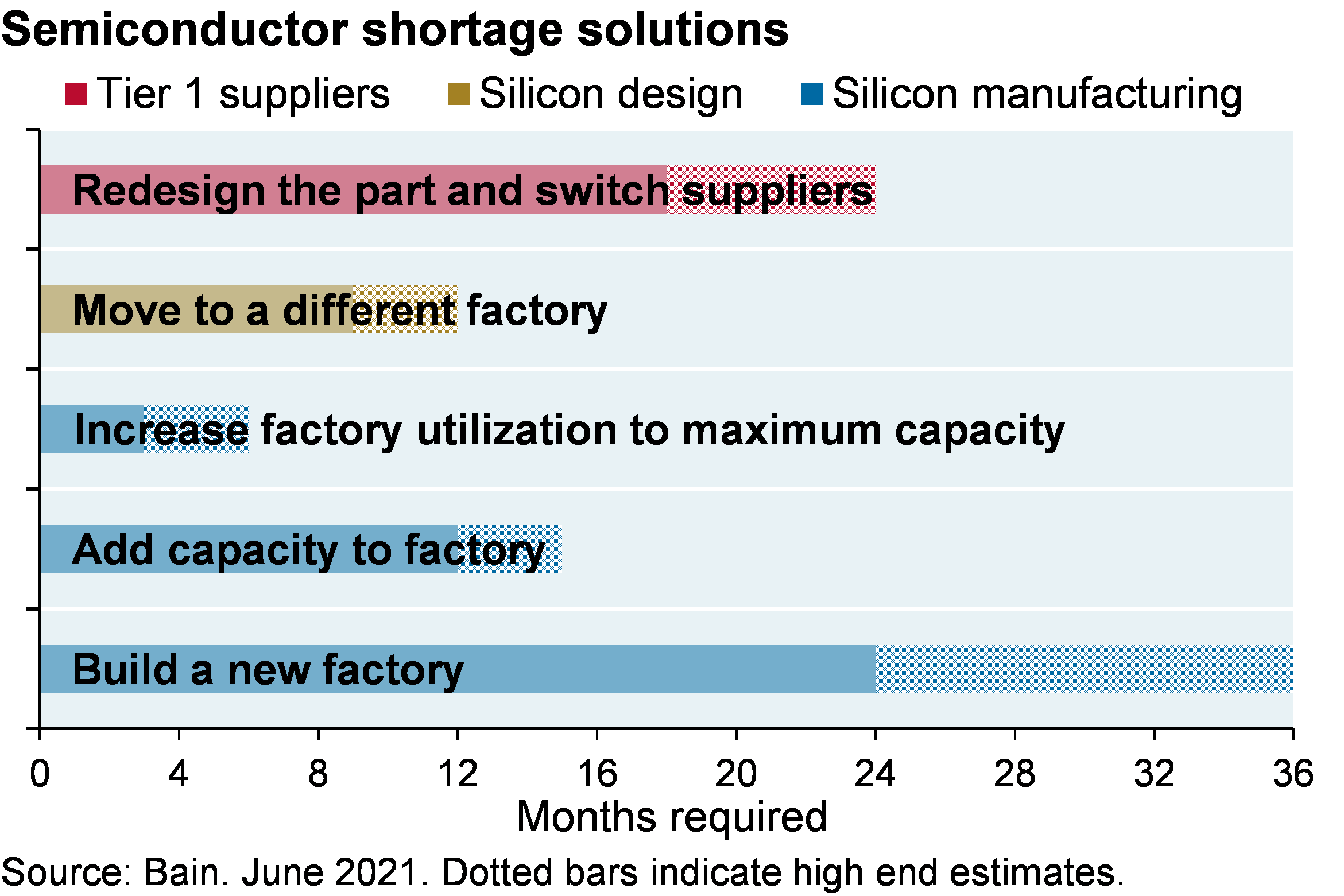

There’s limited economic incentive to build new 200-mm chip plants given wafer-thin margins; only a handful of new ones are planned for 2022. Even so, there’s a few billion dollars being invested to expand capacity by ~20% in existing plants, in which case the semiconductor squeeze may start to ease by Q2 2022. Auto manufacturers are also discussing longer term contracts with Tier 2 suppliers that might incent them to build out new 200-mm capacity. As shown below, adding capacity to existing factories will take a few months at least, in which case the semiconductor shortage will drag on into next year.

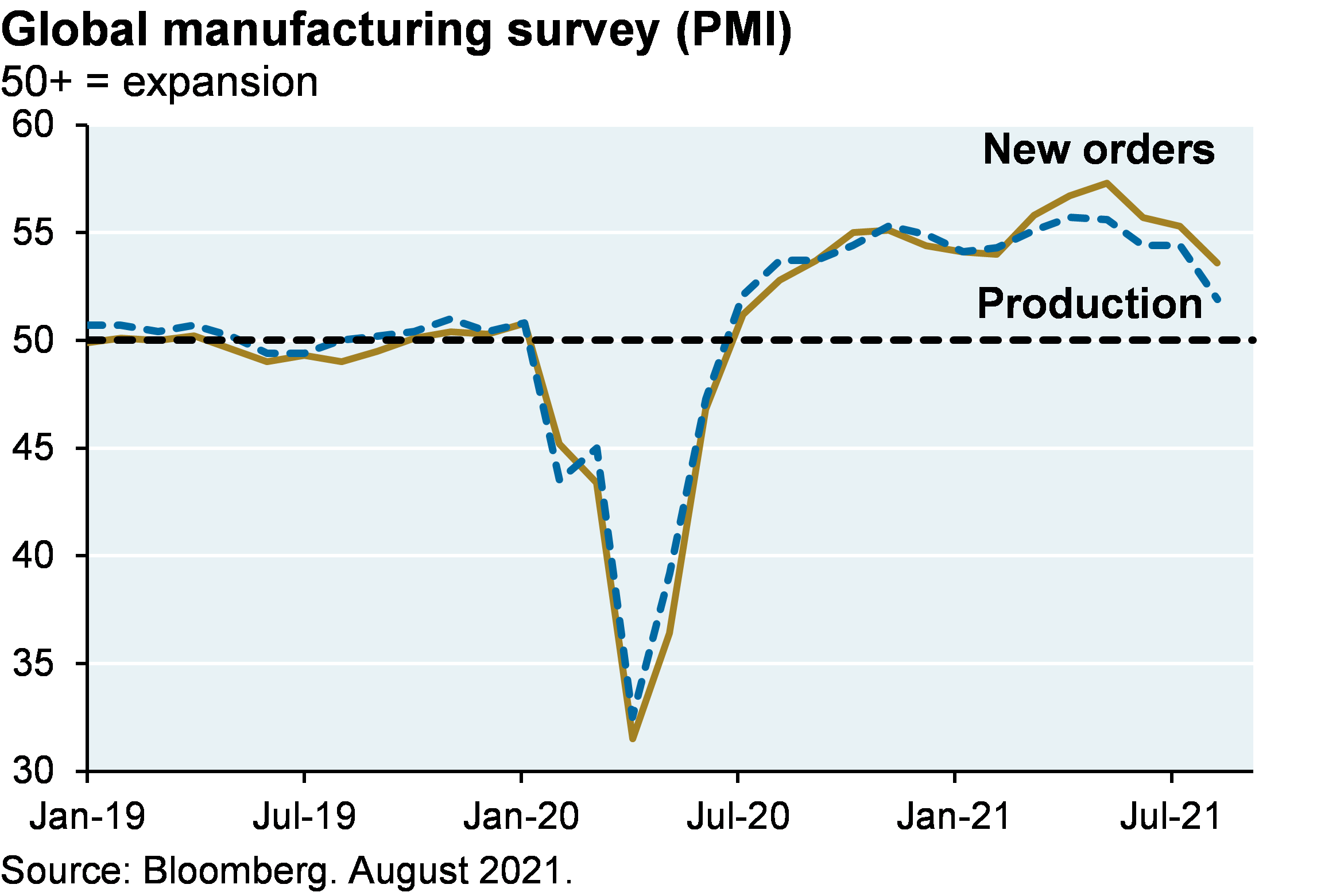

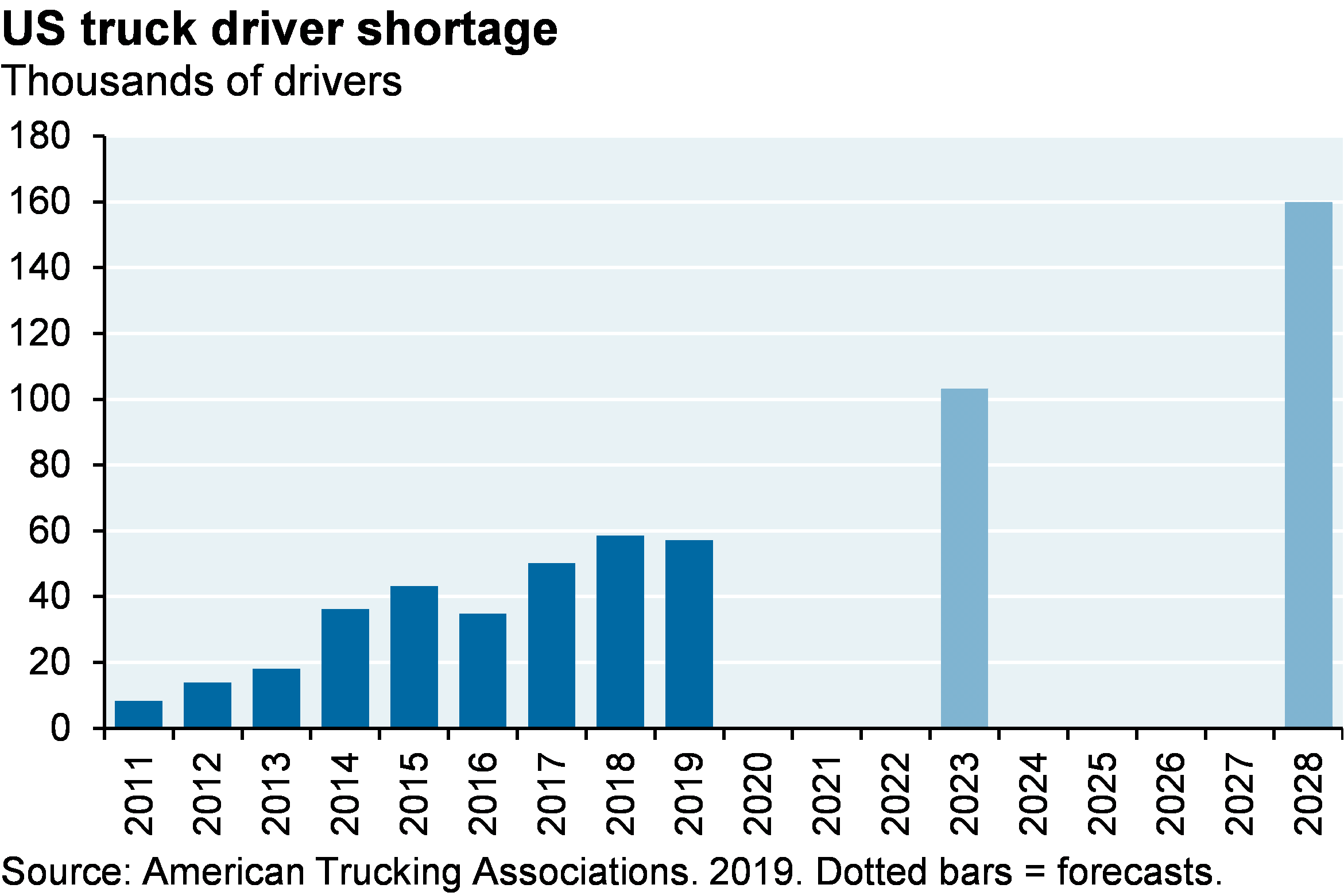

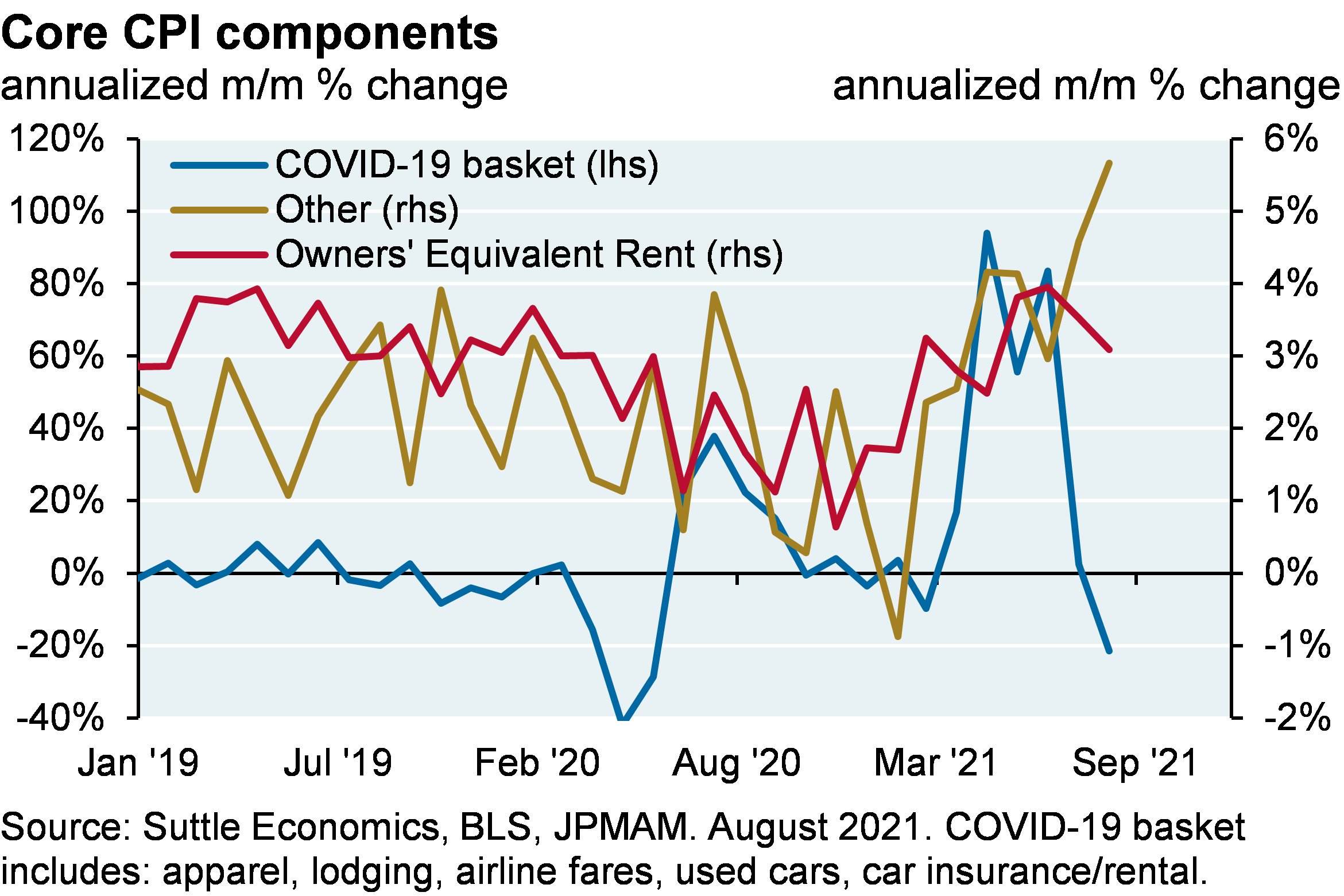

Note that global supply chain problems are not getting better as growth momentum slows, since production growth is declining as fast as new order growth. For all the clients that have asked me about the political and economic problems associated with the rise of autonomous vehicles and more unemployed truckers, I keep telling them they’ve got it backwards: the US has had a trucker shortage for the last few years, and it’s projected to get worse. In other words, COVID has worsened some existing vulnerabilities in the US supply chain, just as global trade is surging. As for the August US inflation report in which CPI came in lower than expectations, that was mostly a function of COVID related declines in airfare, lodging and rental cars. These categories will probably bounce back when the Delta wave fades, and the other categories are still rising sharply.

Bottleneck resolution

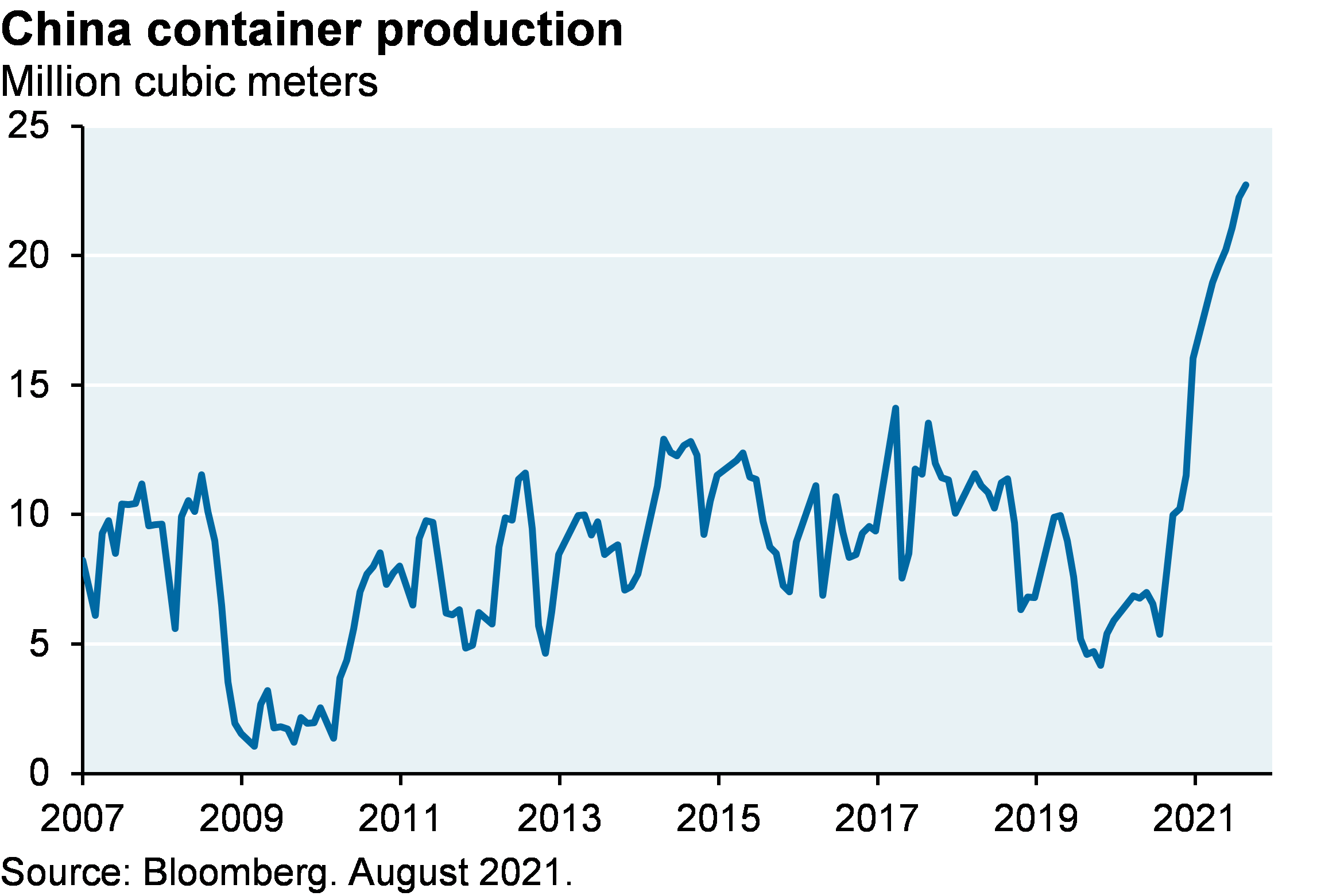

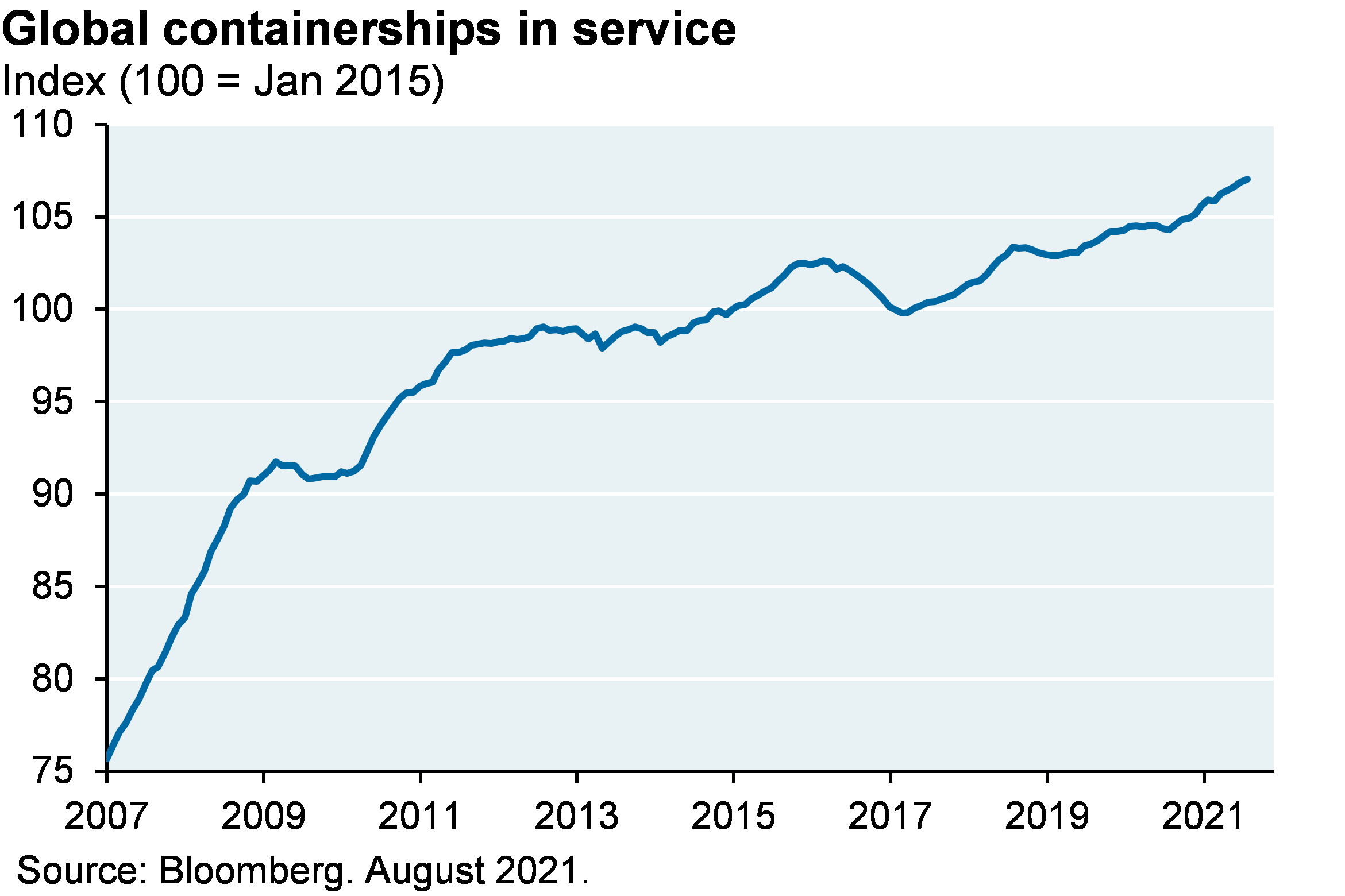

First, the world is going to need more containers, which carry more than 90% of the world’s traded goods. Chinese companies affiliated with its government make 95% of the world’s containers and have ramped up production. The number of containerships in service is rising as well, albeit more slowly; again, China stands to benefit as the world’s largest shipbuilder (37% of the shipbuilding market in 2019 by deadweight, and 45% of all new shipbuilding orders). Another example of how China continues to reap unforeseen economic gains from COVID; another is the rise in global export market share that China has gained vs its Asian export competitors.

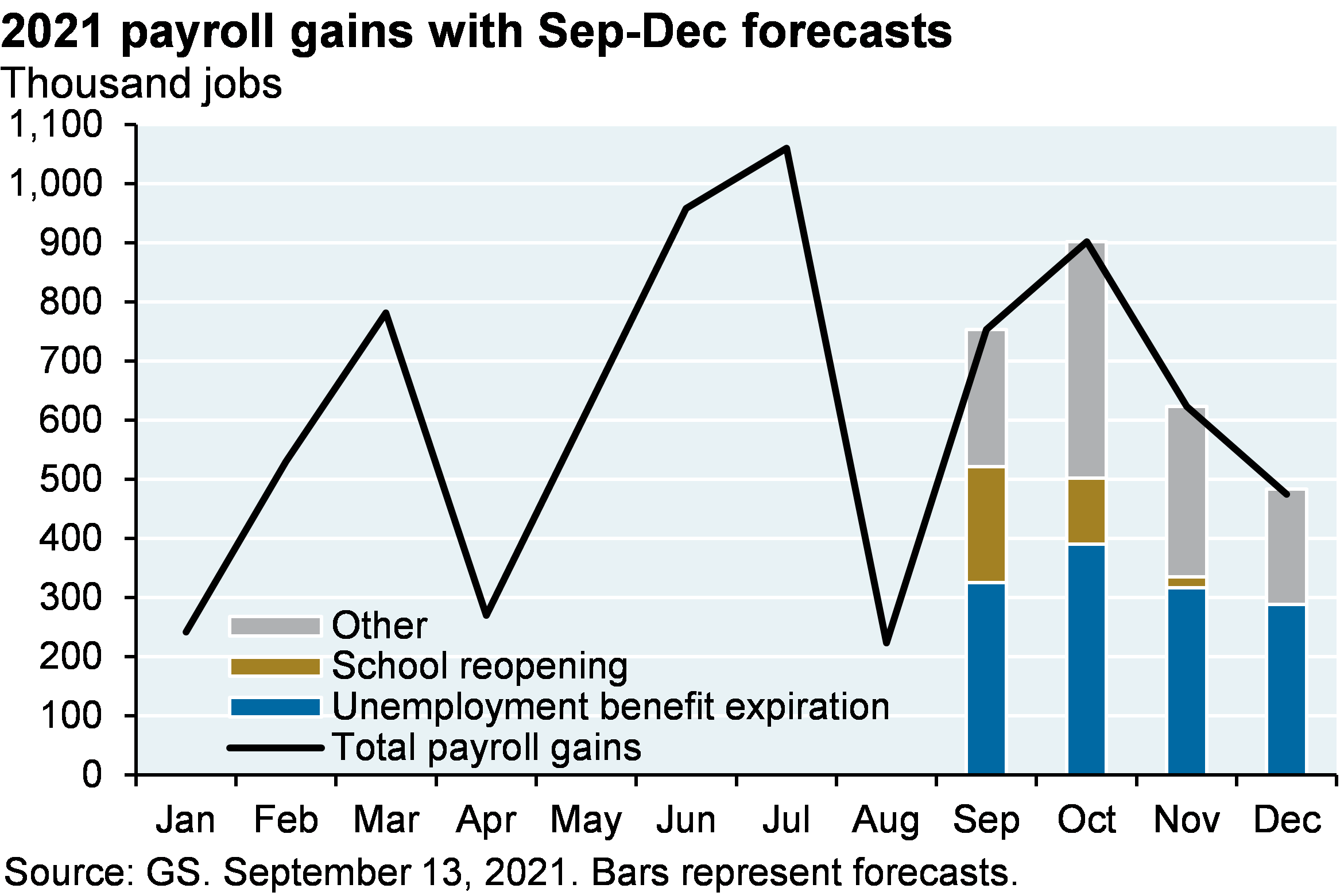

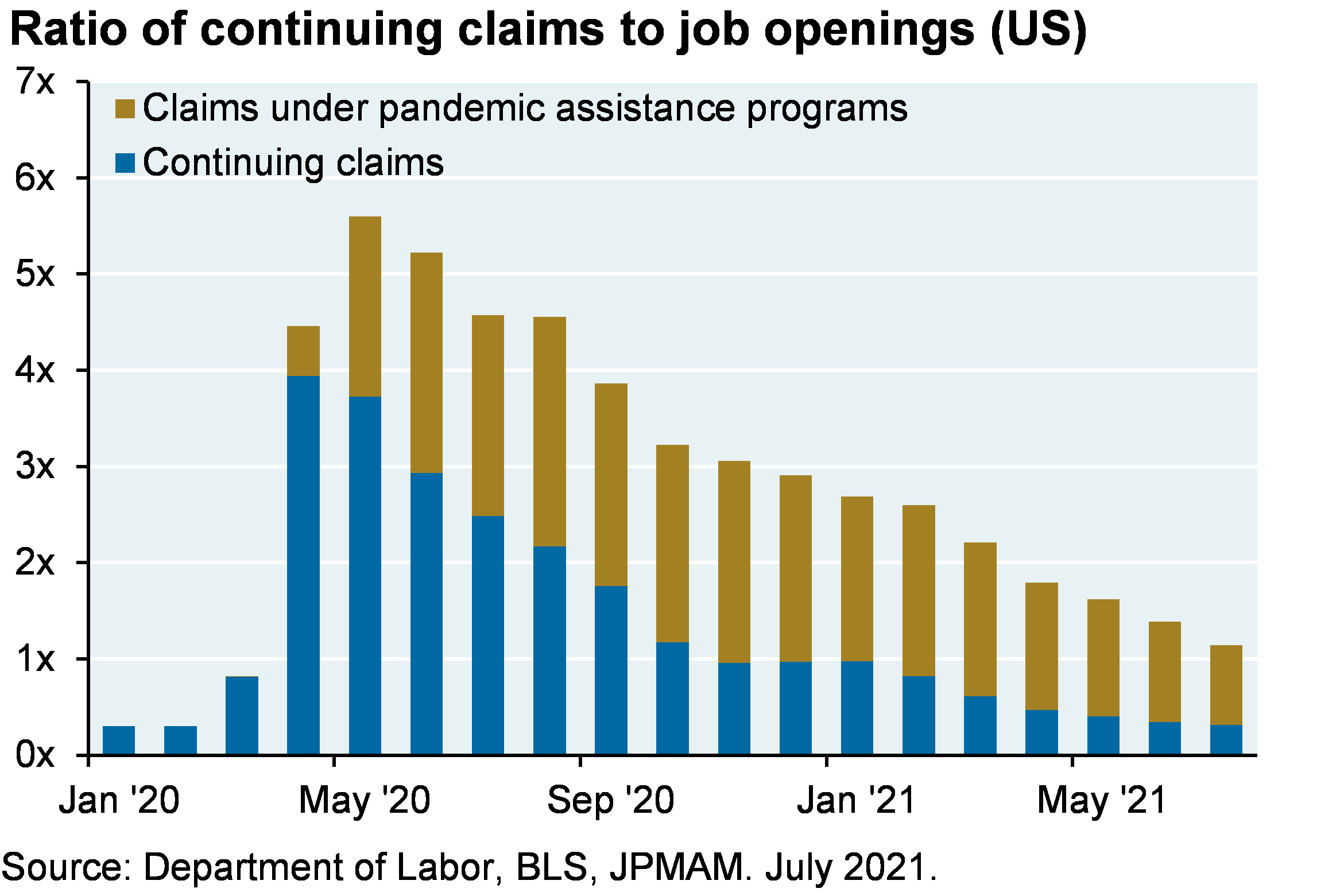

But more containers and containerships won’t solve problems in the West unless other supply chain issues are resolved as well. That will probably require (a) an end to extraordinary housing and income support measures, and (b) less community spread and concern about COVID. So far, most analyses show very little job growth differentials between US states that terminated subsidies vs those that didn’t1. That said, some forecasts call for 1.3 million new jobs by year-end due to expiring unemployment benefits and another 300,000 new jobs due to school reopening. Around 2/3 of continuing claimants receive some pandemic unemployment assistance, which is another sign that such benefits are impacting the labor force participation rate.

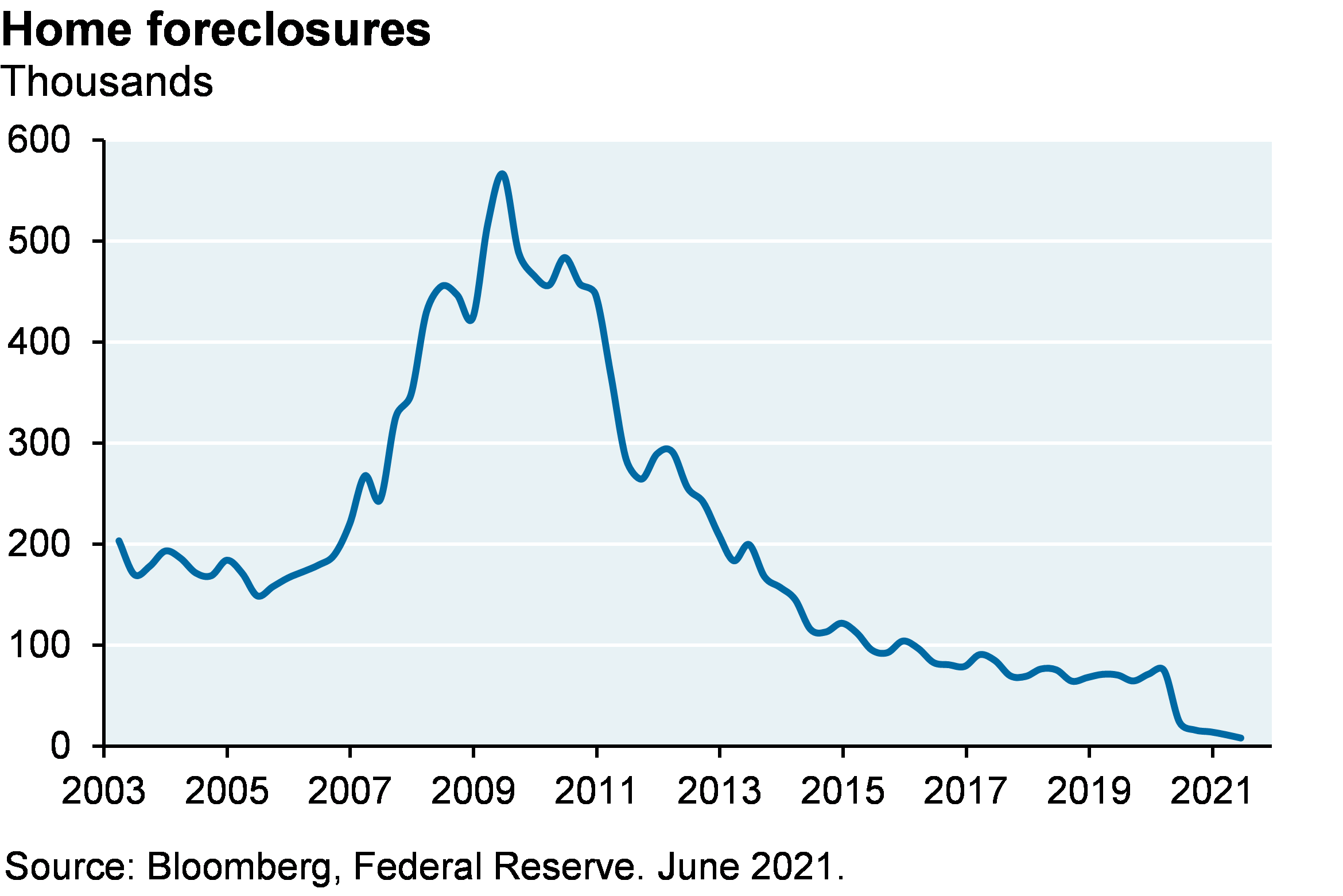

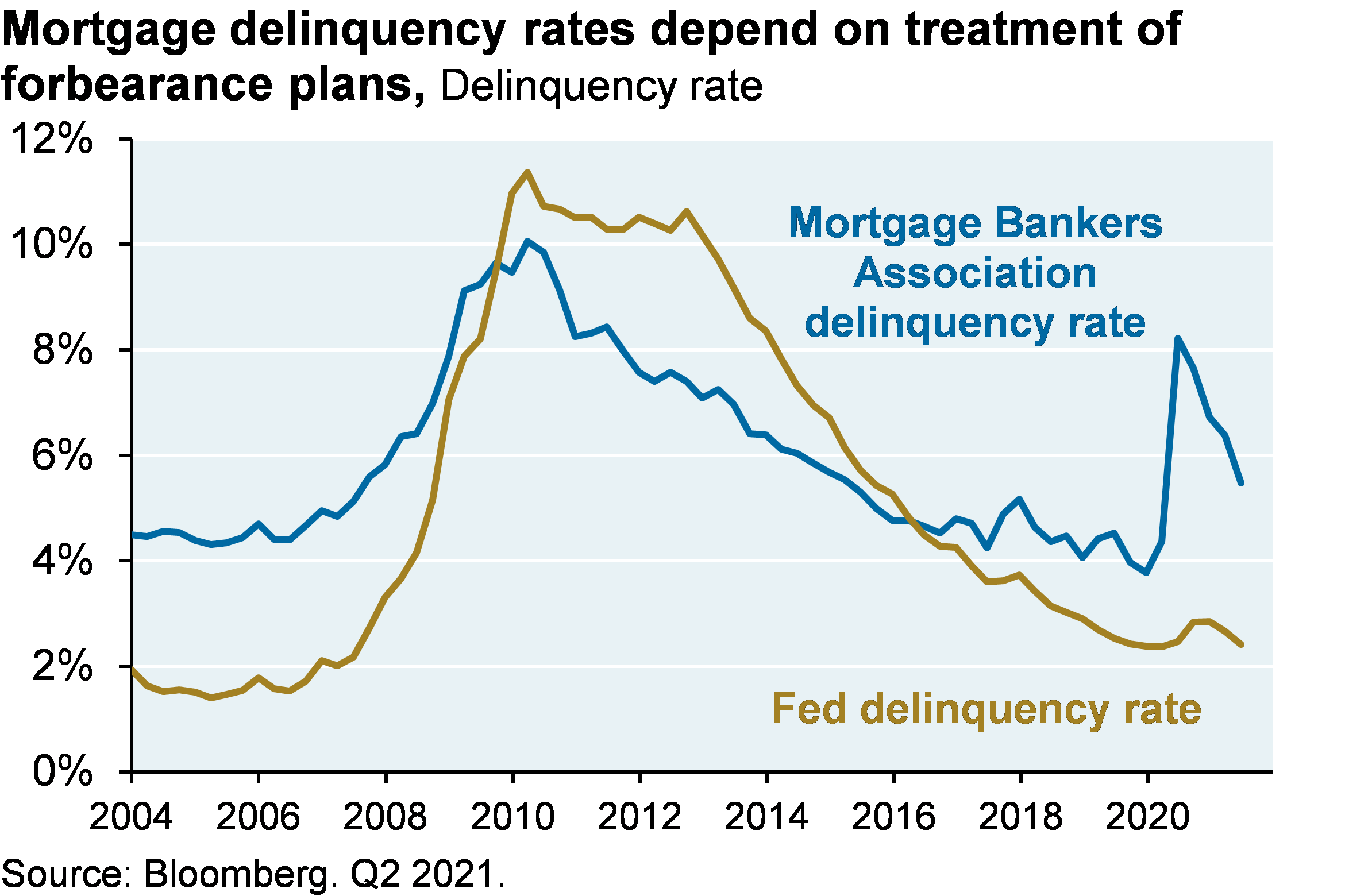

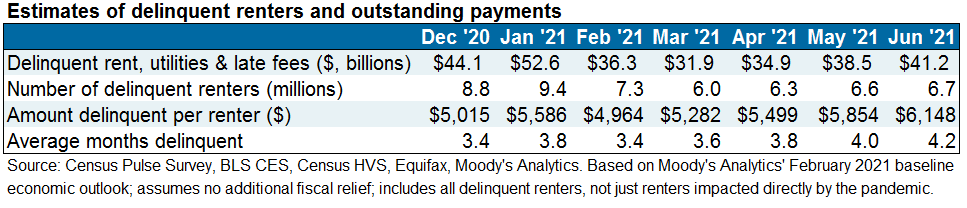

The federal foreclosure moratorium officially ended on July 31. However, we don’t anticipate a sharp rise in new foreclosure filings due to a CFPB rule issued in June that established procedural safeguards that have to be met before foreclosures can begin (hurdles are hard to meet and include provisions that a property has to be abandoned, or that the servicer hasn’t heard from the borrower for an extended period). The new rule expires in December 2021, after which normal foreclosure patterns might resume. Foreclosures fell close to zero in the US once the moratorium was put in place. The second chart shows the gap between the MBA definition of delinquency which defines deferred payments as delinquent, and the Fed definition which does not. See appendix for a discussion of homeowner vs renter treatment.

One more thing on housing: read about the issues with LoanDepot. So, one of many undercapitalized fintech lenders (most of whom have limited special servicing capabilities) allegedly processed thousands of loans without required documents such as employment and income verifications? Color me unsurprised2

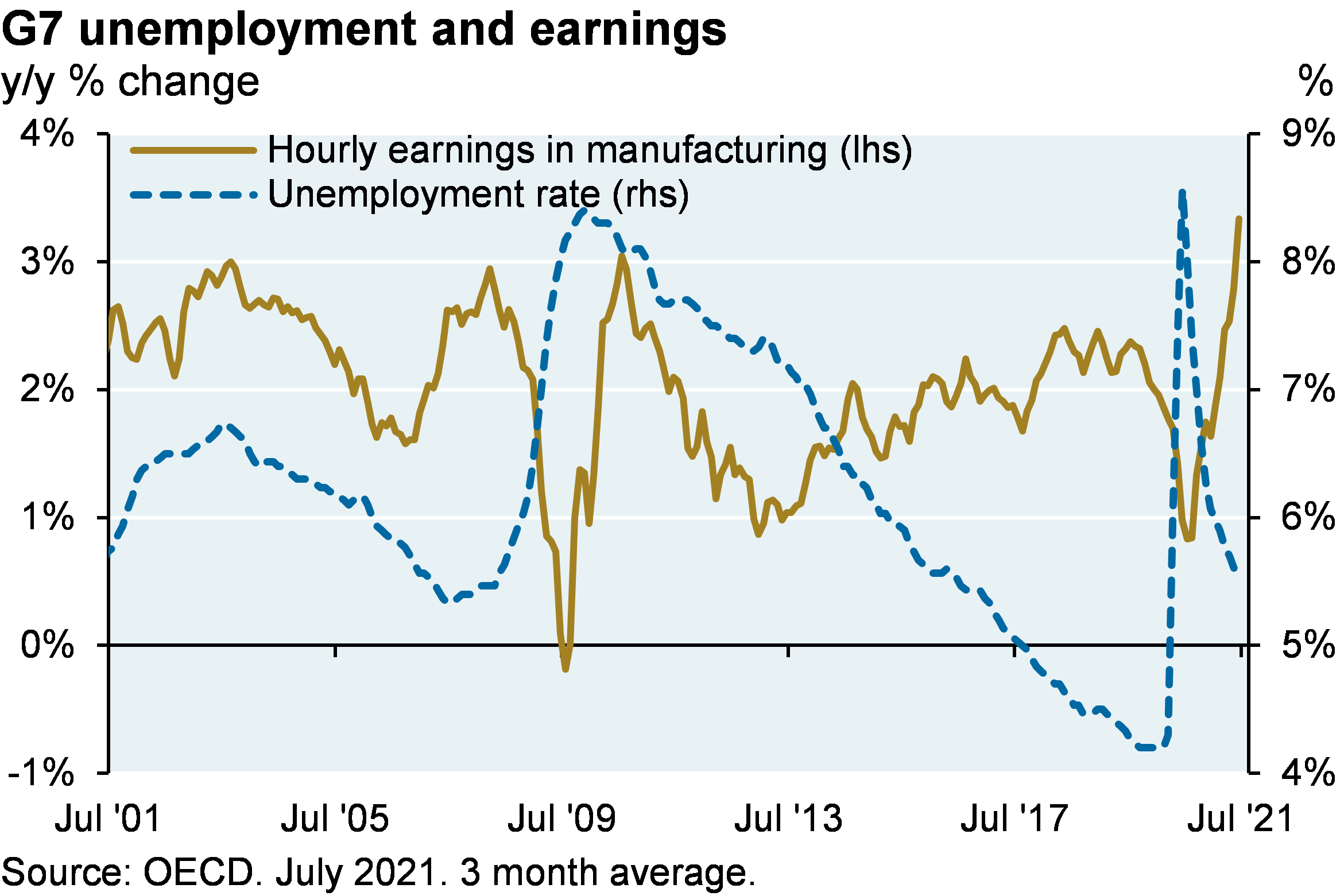

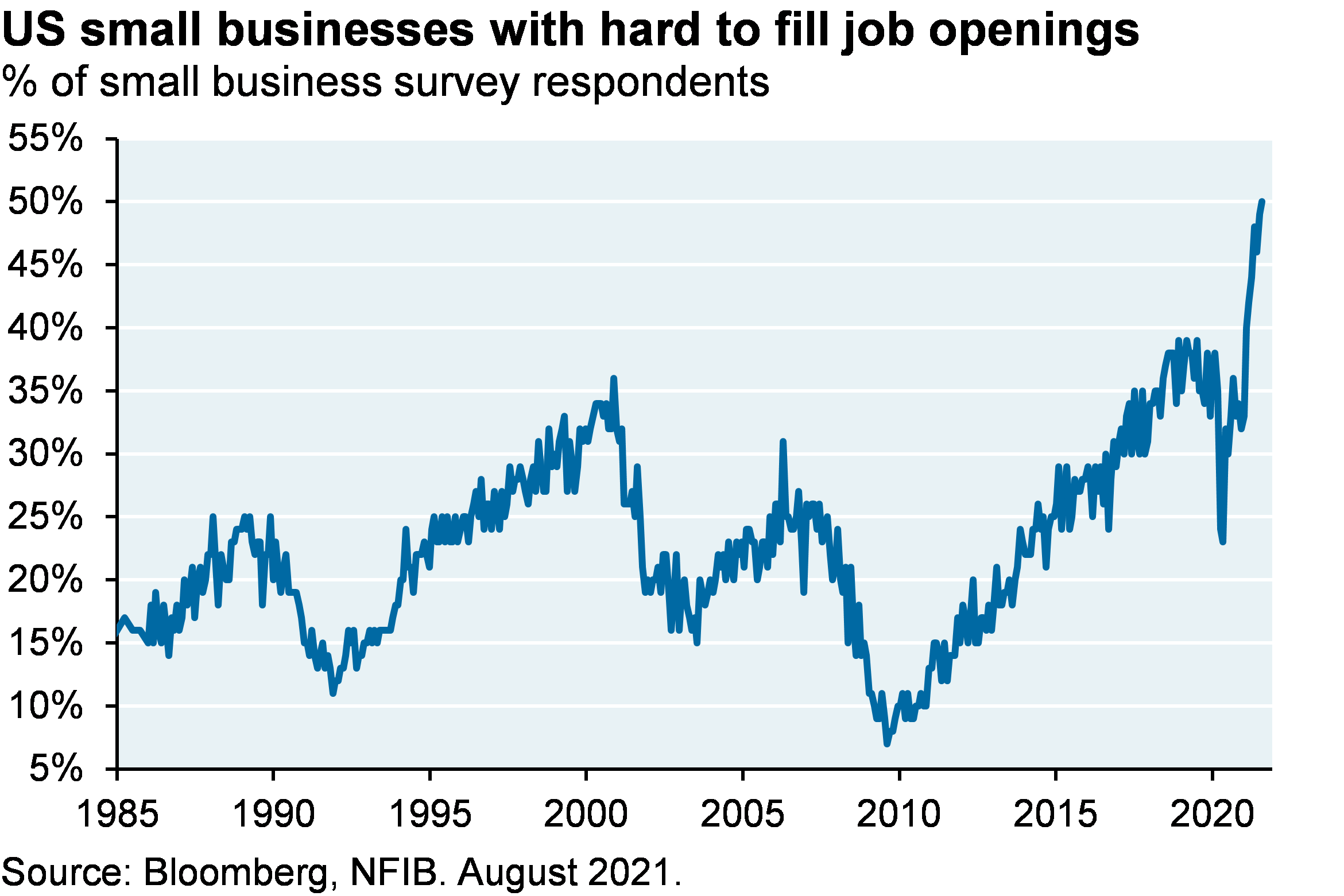

Housing and income policy may have to normalize before labor supplies do. As shown below, G7 manufacturing wages are rising at a very high rate given the prevailing level of unemployment, another sign of labor markets whose supply-demand equilibrium has shifted. By the way, I find it interesting that some people arguing for continued extension of COVID benefits also argue for the largest amount of new Congressional spending ($3.5 trillion), without explaining what that might do to current labor shortages, where all these new workers are supposed to come from and how all that spending might impact inflation and Fed policy. In August, 50% of small business owners said they had job openings they already couldn’t fill, the highest level on record.

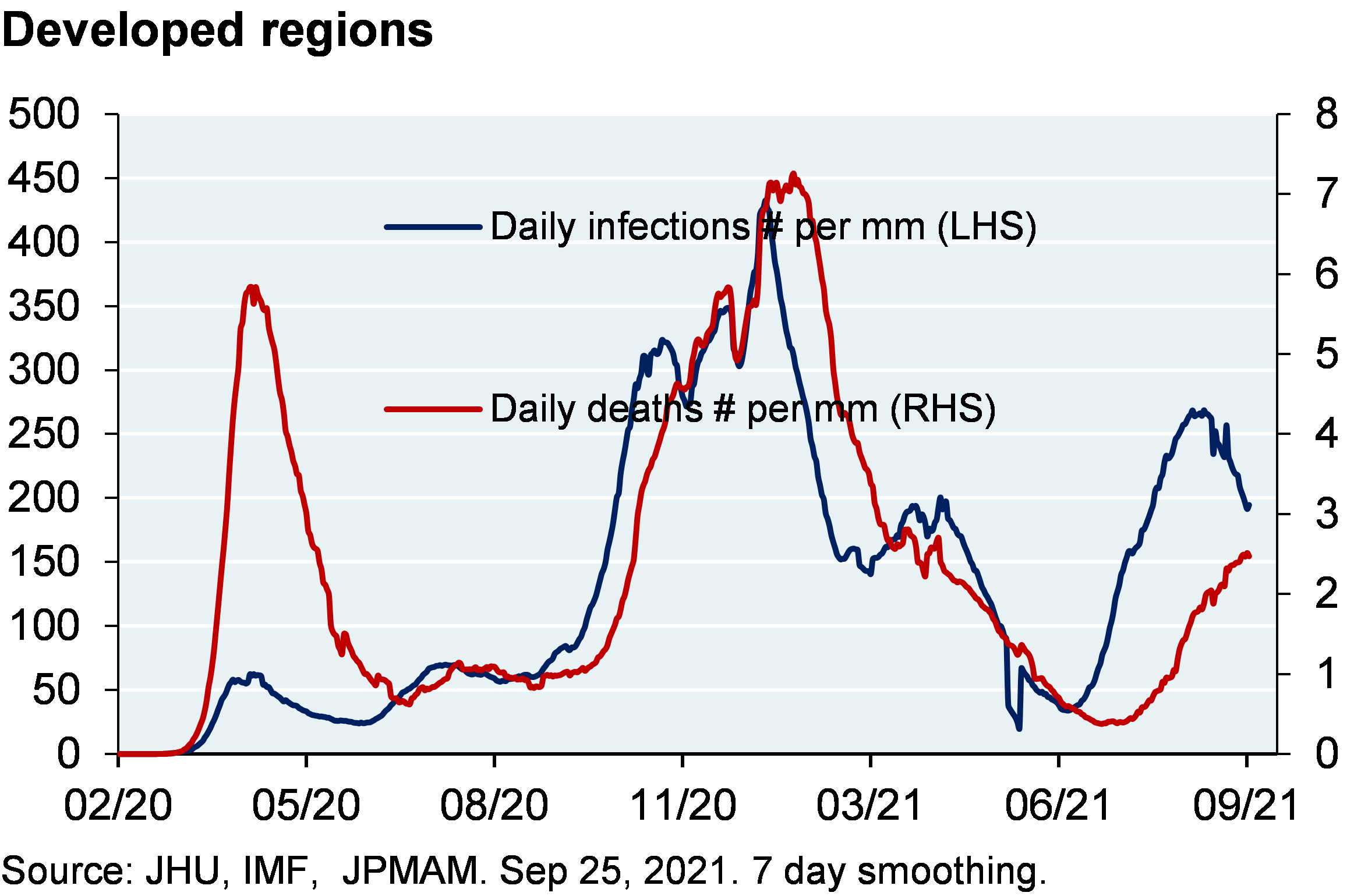

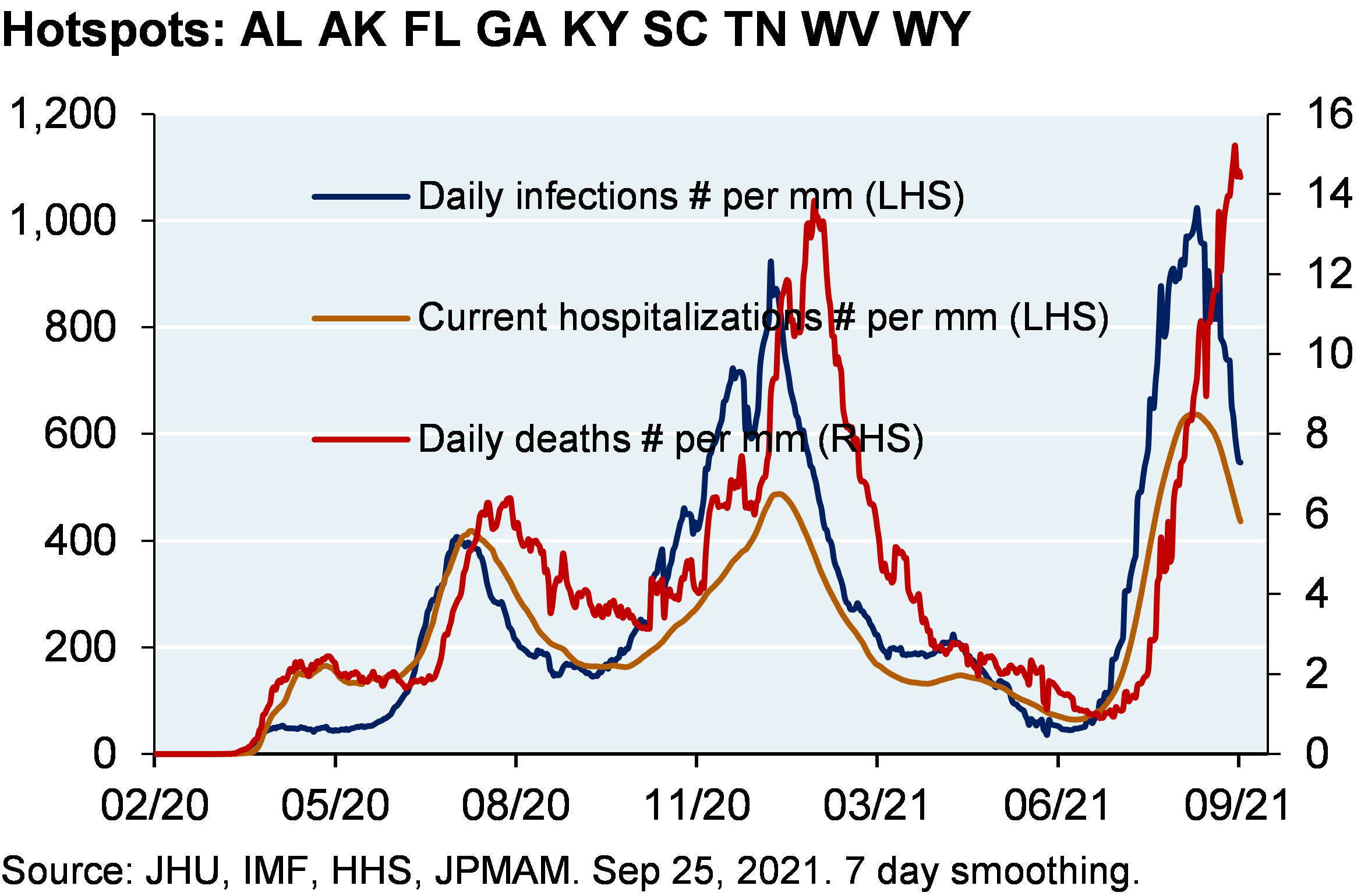

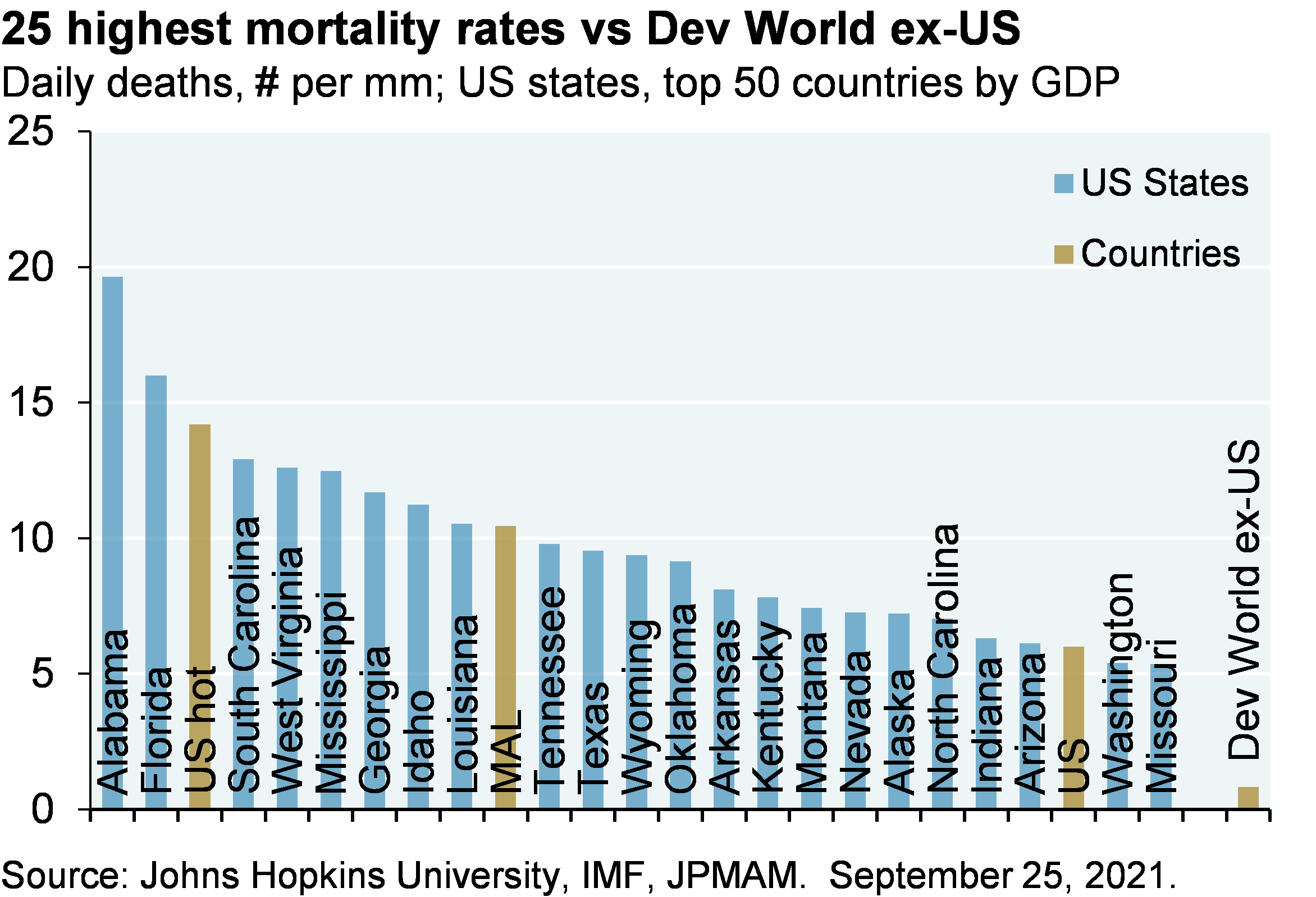

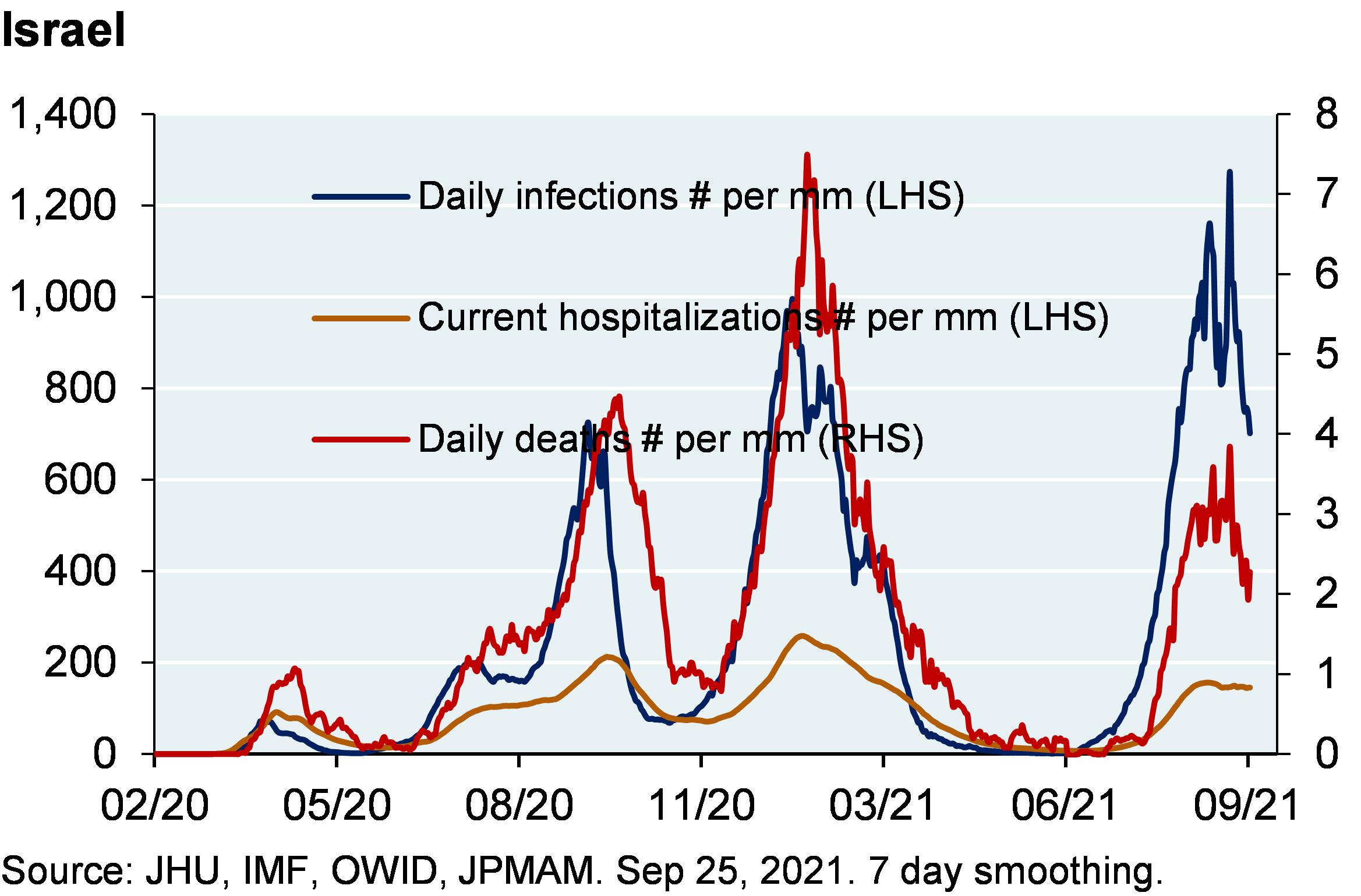

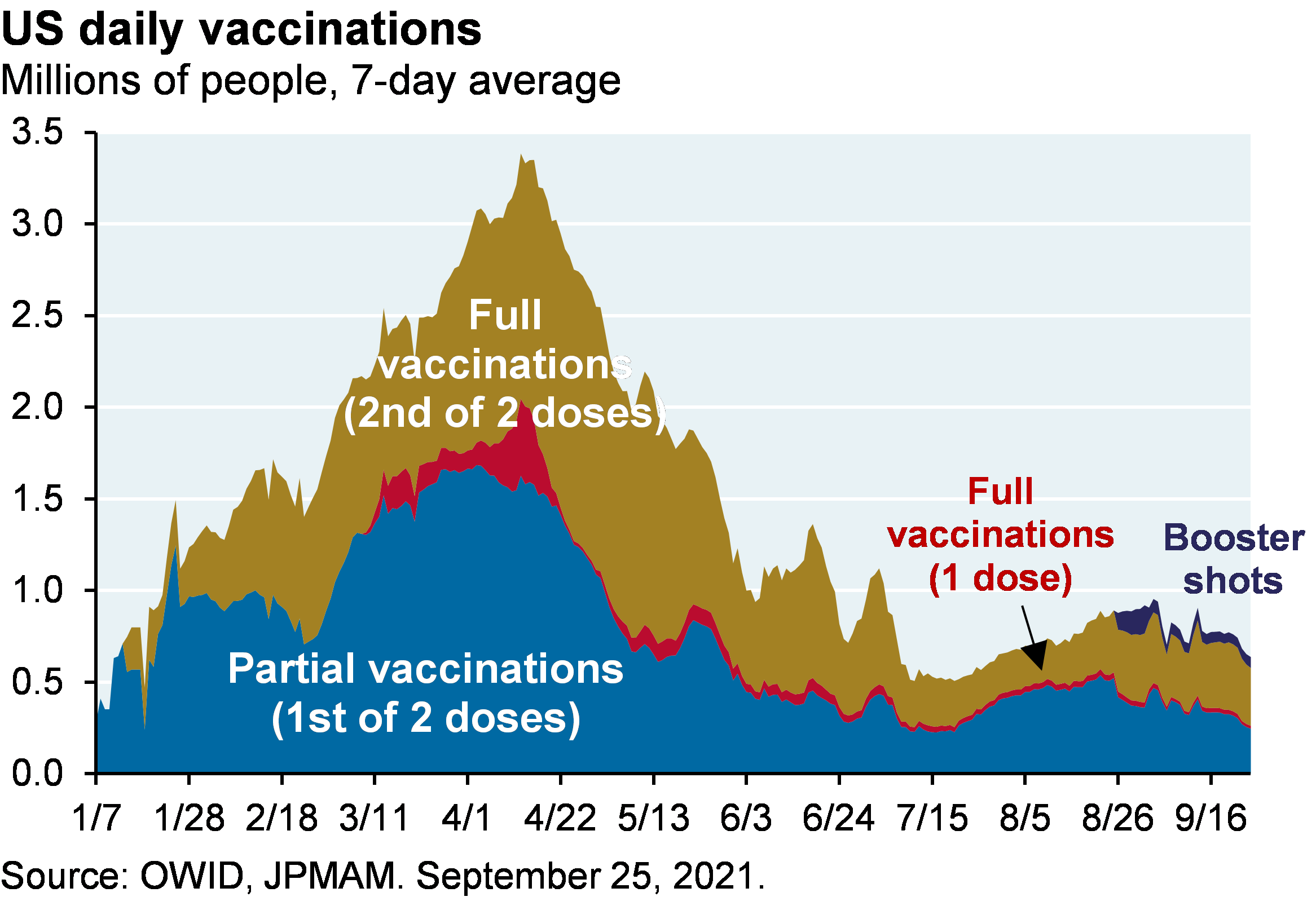

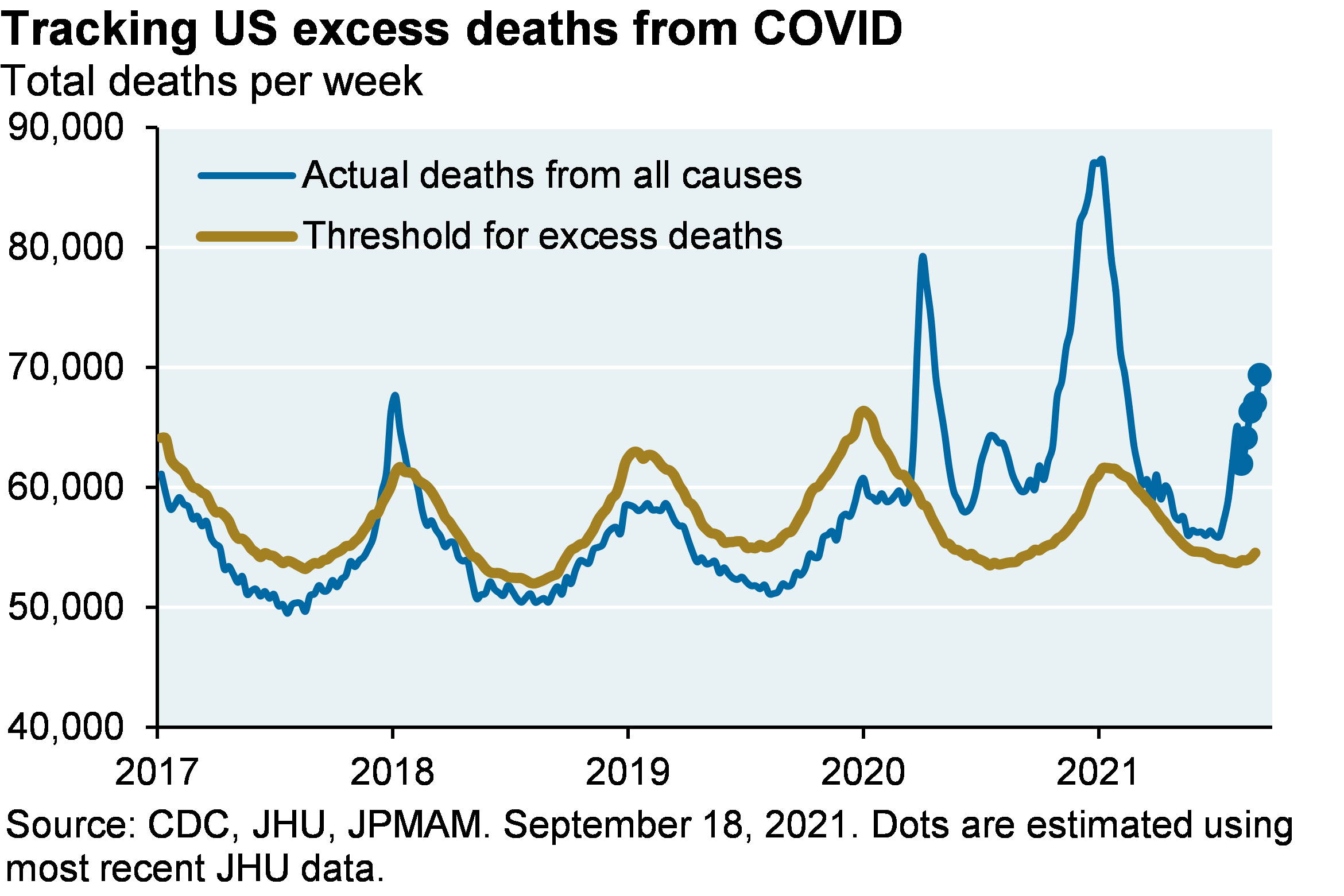

As for COVID, concerns may dissipate in the next few months. As we explained on our August webcast, this fall was going to be a very bad one in the US. Even so, given the high degree of Delta variant contagiousness, a combination of vaccination and acquired immunity should drive down pandemic measures substantially by November. The latest infection and hospitalization data from Hotspot states, horrific as they are (i.e., the world’s highest reported mortality rate) are beginning to roll over; mortality should follow. For anyone that disbelieves COVID mortality data, see the sixth chart below: there has been another surge in mortality from all causes in the US relative to seasonal trends. If you can think of another reason for this other than COVID, please let me know. The biggest risk to this outlook is fading immunity of vaccinated people; we will know over the next couple of months how this plays out in the US. Booster shots in Israel appear to drive antibody levels up substantially, and also result in Pfizer efficacy vs severe infection that rises above 90% again.

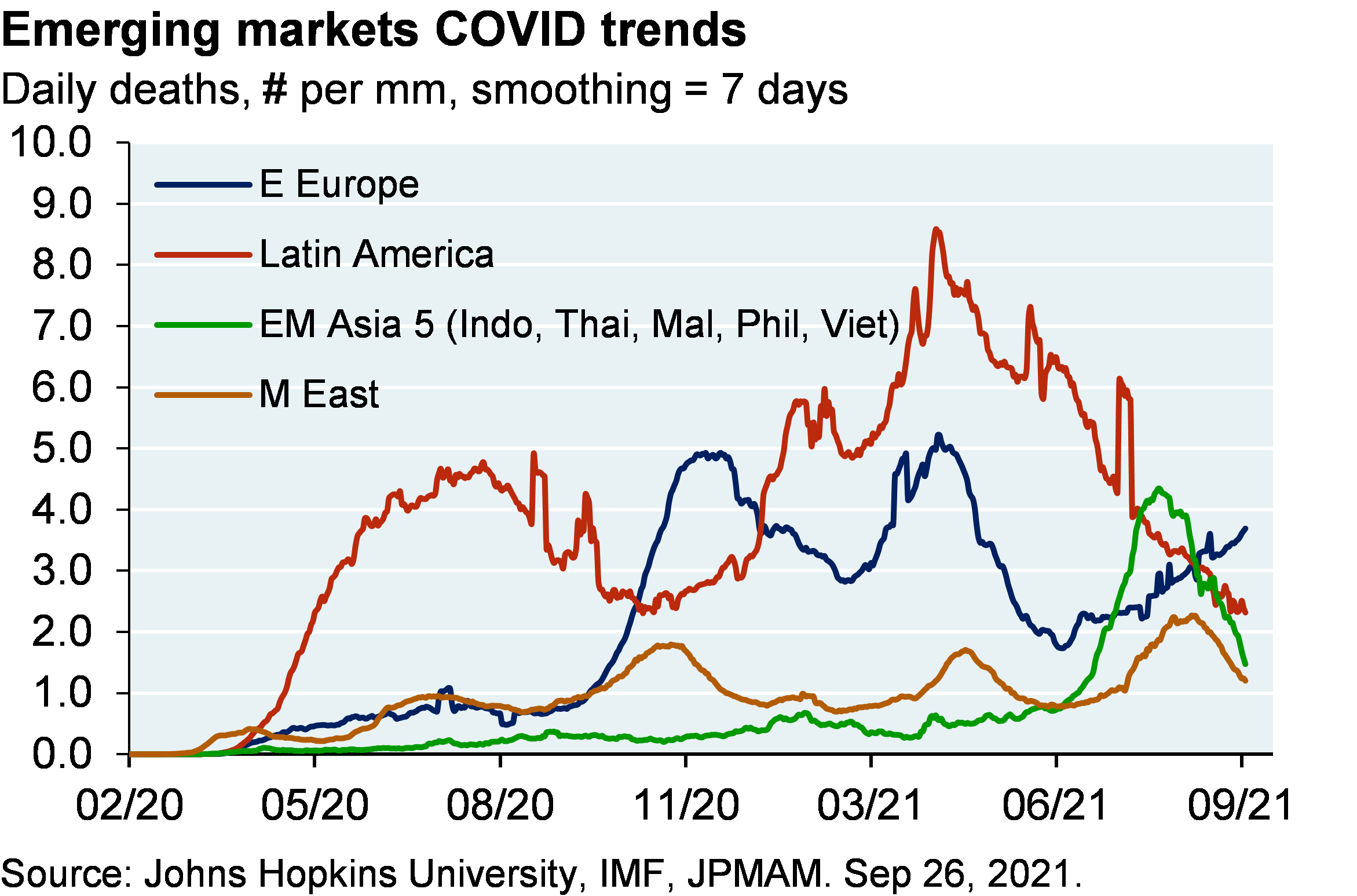

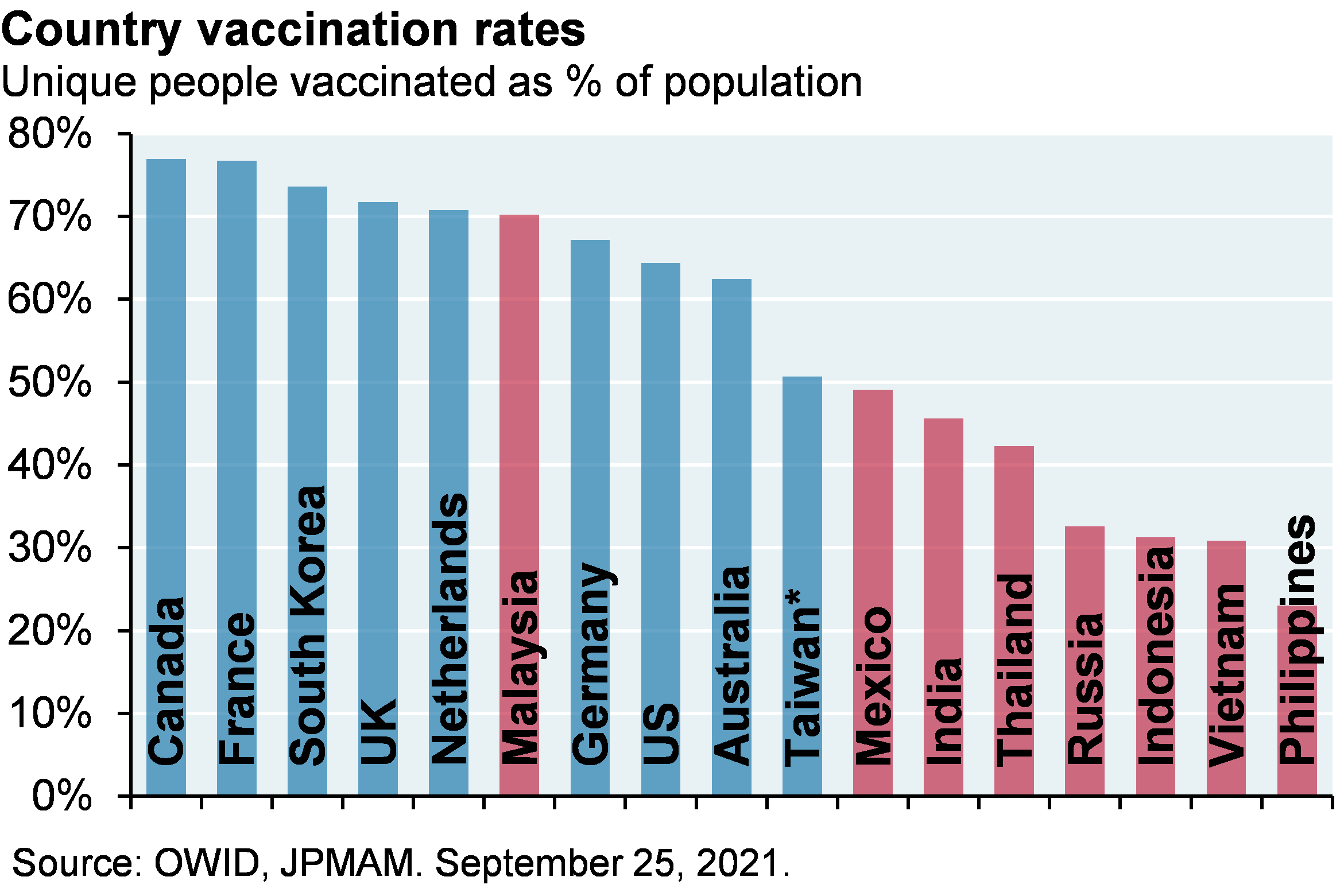

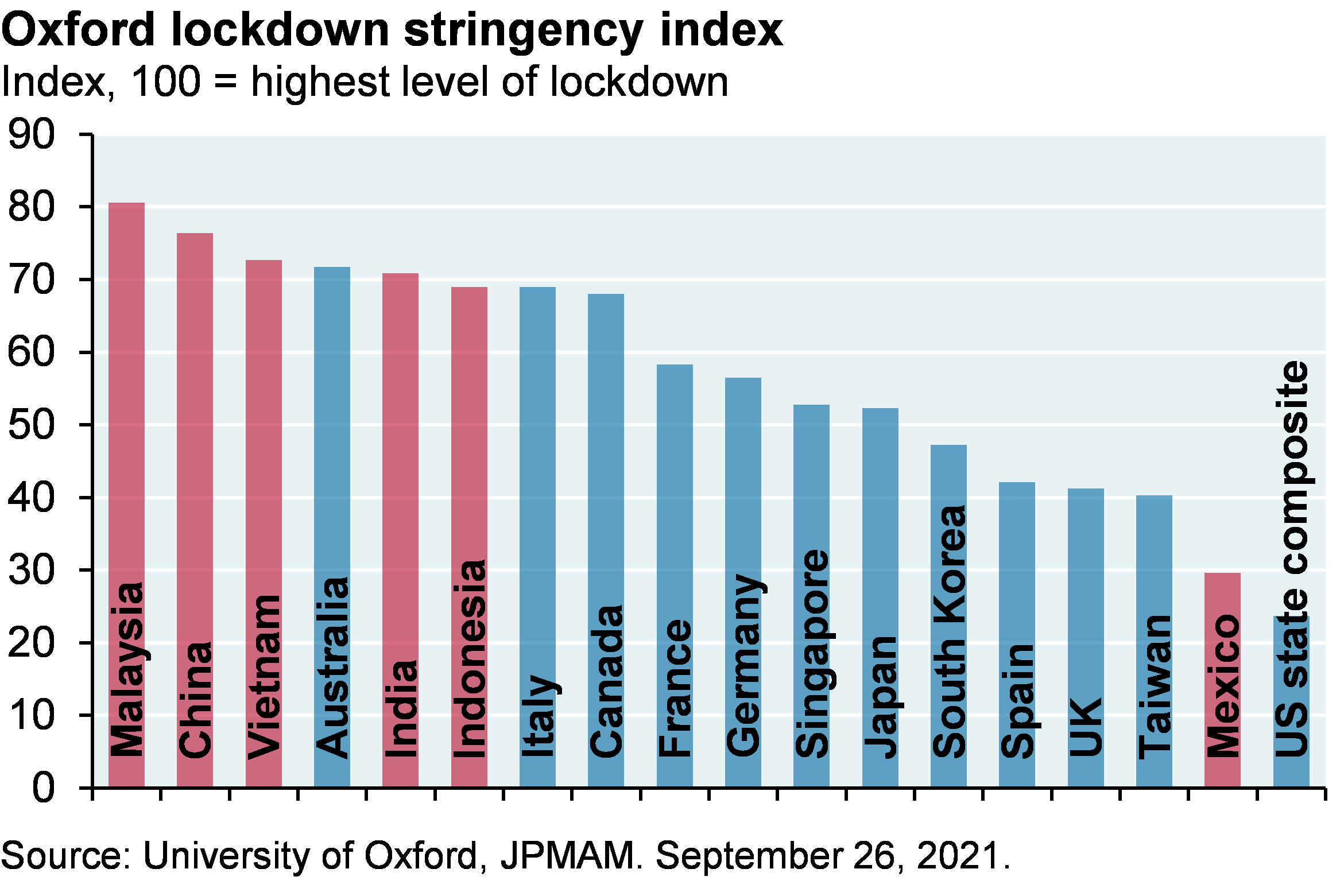

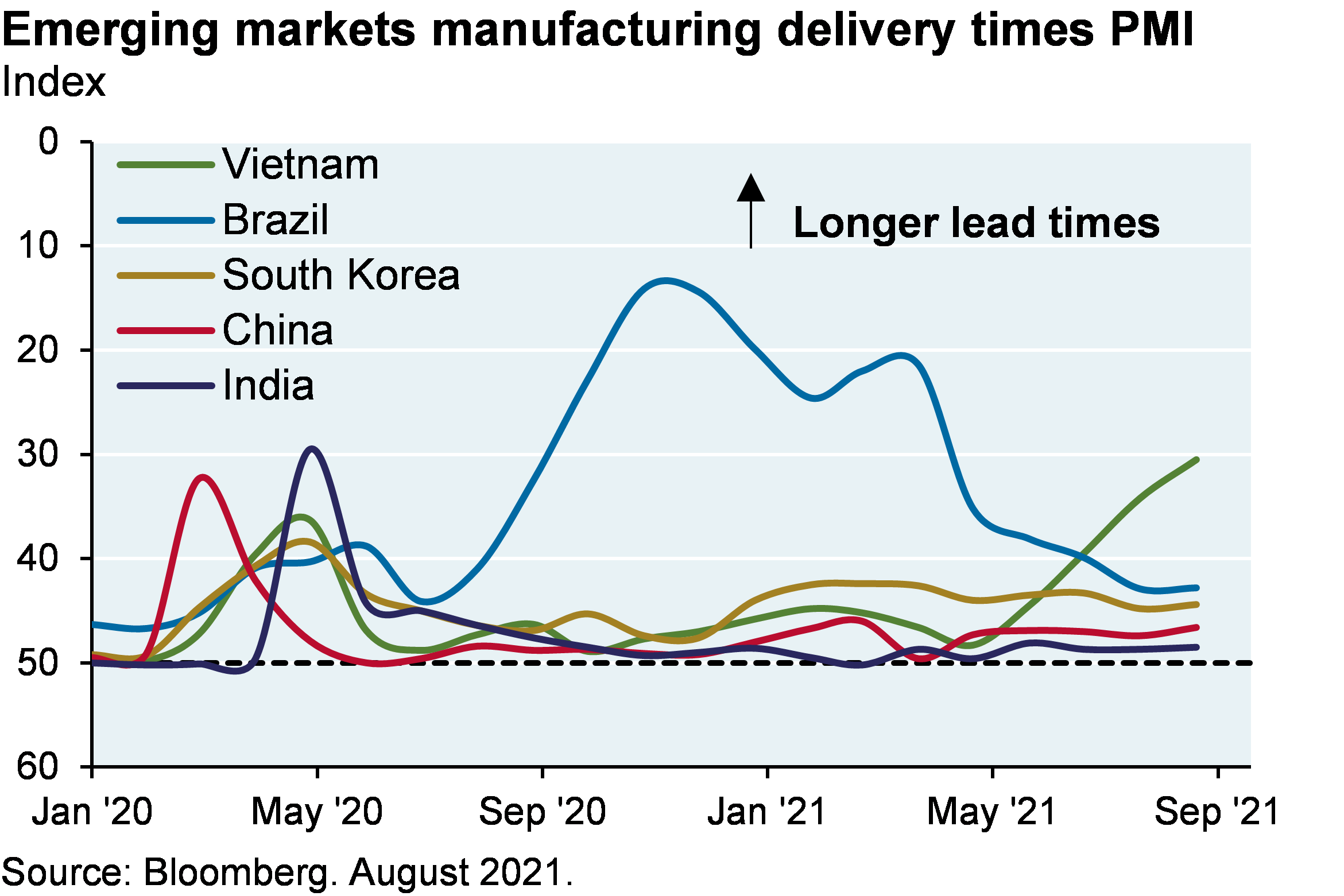

Developing world infections and mortality are declining due to exhaustion of Lambda and Gamma variants in Latin America and the decline in the Delta variant in Asia (although mortality is rising in Eastern Europe again). Many Asian countries have higher COVID stringency rules than developed countries, an indication of how seriously govt’s view the risks and the ability of their healthcare systems to respond to it. Emerging markets are not the epicenter of most supply chain problems, at least as measured by supplier delivery times. But countries like Malaysia play an outsized role in the semiconductor food chain due to its role as a major center for chip testing and packaging, the last step in the semiconductor food chain which is also more labor-intensive than automated wafer fabrication. The delta variant has caused Infineon, NXP and STMicroelectronics shutdowns in Asia, which resulted in component shortages at Nissan, Toyota, Ford and GM operations elsewhere. Malaysia is also a large producer of multilayer ceramic capacitors, used in smartphones and cars.

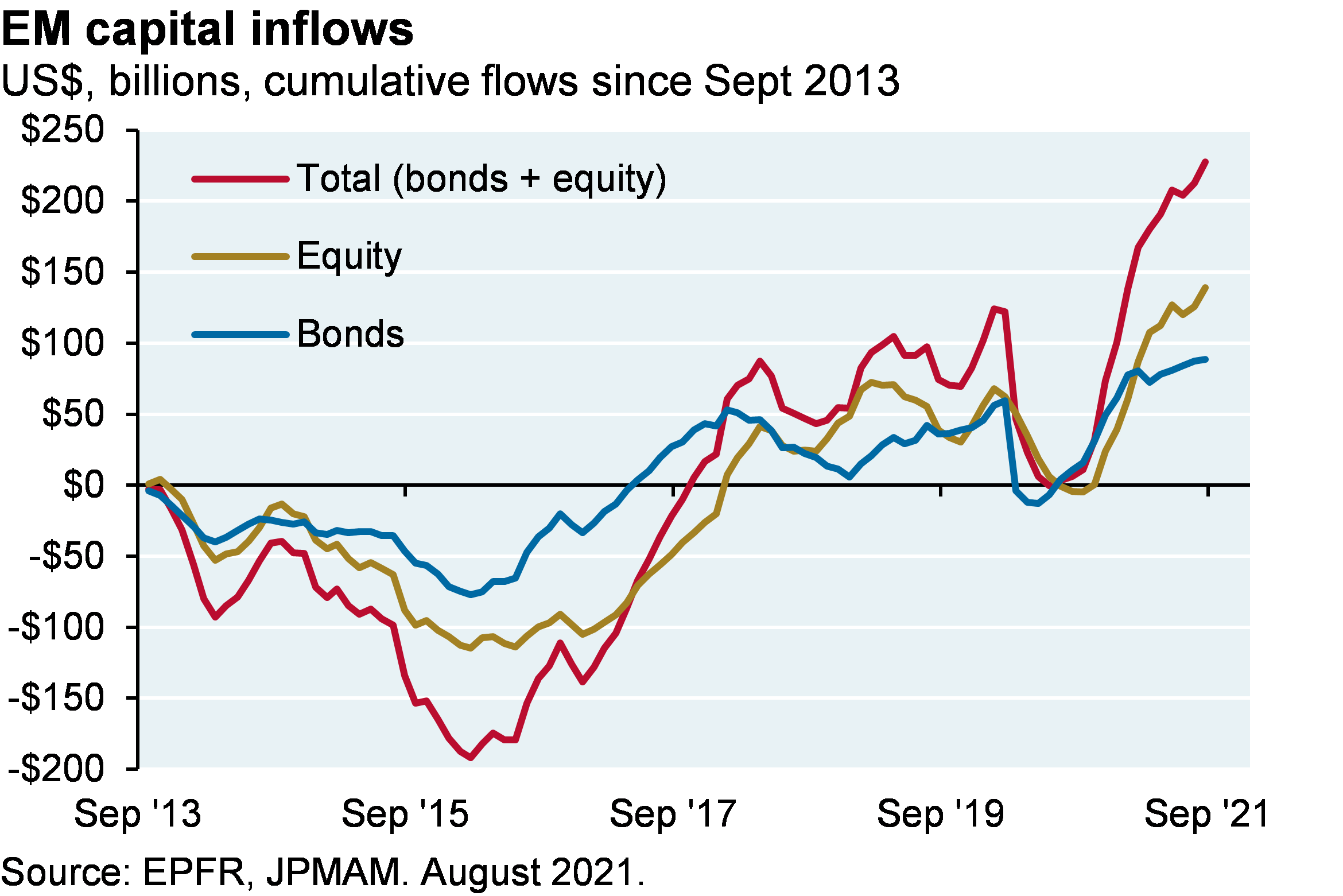

Some good news on Asia. As noted above, infections and mortality are finally rolling over. Vaccination rates have hit 70% in Malaysia; while they are still less than 50% in Indonesia, Thailand, Philippines and Vietnam, acquired immunity appears to be playing a role now as well. Furthermore, mRNA vaccines should make greater inroads in the entire region in 2022, displacing Chinese vaccines with lower observed efficacy3. Finally, capital flows are returning in anticipation of less severe bottleneck issues ahead.

Appendix: Homeowners vs Renters and US housing policy

- As discussed in the "Bottleneck Resolution", the federal foreclosure moratorium has expired and there are safeguards in place which should keep the number of foreclosures low until early next year when a CFPB rule expires. The federal eviction moratoria are separate policies; some have already expired, while GSE and FHA versions will expire at the end of September. Eviction rules cover renters and homeowners, while foreclosure rules only apply to homeowners. Several Democratic Senators have introduced legislation to reinstate federal eviction moratoria after the Supreme Court ruled that the CDC overstepped its authority in mandating it

- States can apply their own foreclosure and eviction moratoria alongside the federal government; banks are required to follow both. There are currently live foreclosure moratoria in NY, Oregon and DC

- While federal eviction moratoria prohibited evictions of renters and homeowners, the treatment for missed payments is different. For example, delinquent renters at the end of the moratorium are treated differently than homeowners who missed payments while in a CARES Act forbearance. Homeowners with federally backed mortgages (or with mortgages from banks applying this approach to all borrowers at their discretion) are allowed to defer missed payments and are not considered to be delinquent. In these cases, homeowners that don’t pay will not face immediate payment of accrued balances, which in most cases will be added as a balloon at the end of their mortgages. Banks generally record unpaid interest as current on an accrual basis. Finally, there are programs in place to modify mortgages for borrowers unable to resume their prior payments due to financial distress.

- Renters, however, are not explicitly allowed to defer; the eviction moratorium simply prohibits landlords from evicting them for non-payment. Renters could face immediate payment of accrued amounts, with any negotiated terms up to the landlord. In addition, non-payment could affect a renter’s credit score, while the same is usually not the case with homeowners under the circumstances outlined above.

- The Federal Emergency Rental Assistance program made $47 billion in funding available for tenants and landlords to be distributed by states and local governments. This funding was aimed at helping tenants cover rent, back rent and utilities as well as helping landlords cover mortgage payments. However, only $5 billion of this program was distributed as of July 2021.

- The National Equity Atlas estimated that as of mid-August 2021, 15% of renters (5.9 million renter households) were behind on rent payments. This compares to ~7% of renters unable to pay rent in 2017.

- Landlords who hold federally backed mortgages were eligible for the federal mortgage and foreclosure relief programs, which were extended through June 30, 2021.

- In addition, some states established their own rental relief programs. For example, New York’s landlord loan program provides loans to small landlords with a loss of rental income, and California’s rental assistance program helps both tenants and landlords cover rent and mortgage payments at the expiration of the eviction and foreclosure moratorium

1 “Estimating the Impact of Unemployment Insurance Benefit Expiration on Employment Using August Microdata”, Joseph Briggs, Goldman Sachs, September 16, 2021.

2According to a paper released by the Philadelphia Federal Reserve, 70% of the massive rise in fintech loans is simply due to regulatory arbitrage rather than fintech lenders having superior technology or lower costs. Also: shadow banks now control the riskiest segment of the market (FHA). You get what you pay for. See “Fintech, Regulatory Arbitrage and the Rise of Shadow Banks”, Buchak et al, NBER, 2017.

3"Ravaged by Delta outbreak, Southeast Asia shifts away from China’s vaccines”, Washington Post, August 10

Dude, Where’s My Stuff?

The global supply chain mess will require increased vaccination and acquired immunity, semiconductor capacity expansion and the end of extraordinary housing/labor supports to resolve. A close look at some very anomalous charts on shipping, semiconductors, inventories, labor shortages, foreclosures and mortality.

FEMALE VOICE:

This podcast has been prepared exclusively for institutional, wholesale, professional clients and qualified investors only as defined by local laws and regulations. Please read other important information which can be found on the link at the end of the podcast episode

MR. MICHAEL CEMBALEST:

Good morning everybody. This is the late September Eye on the Market podcast. I’m recording this from a CEO event in Ennis, Montana. It’s very beautiful here, but it’s not highly vaccinated. All the CEOs are telling me more or less the same thing. They intend to hire more people. It’s very difficult to find people. The COVID situation is making the challenges even greater. And they’re all experiencing pretty substantial delays in the supplier delivery lays with respect to manufactured goods. And this week’s Eye on the Market gets into this whole supply chain mess. And one of the fascinating things about this is the attribution of these problems to the shipping cost discrepancies between eastbound and westbound freight.

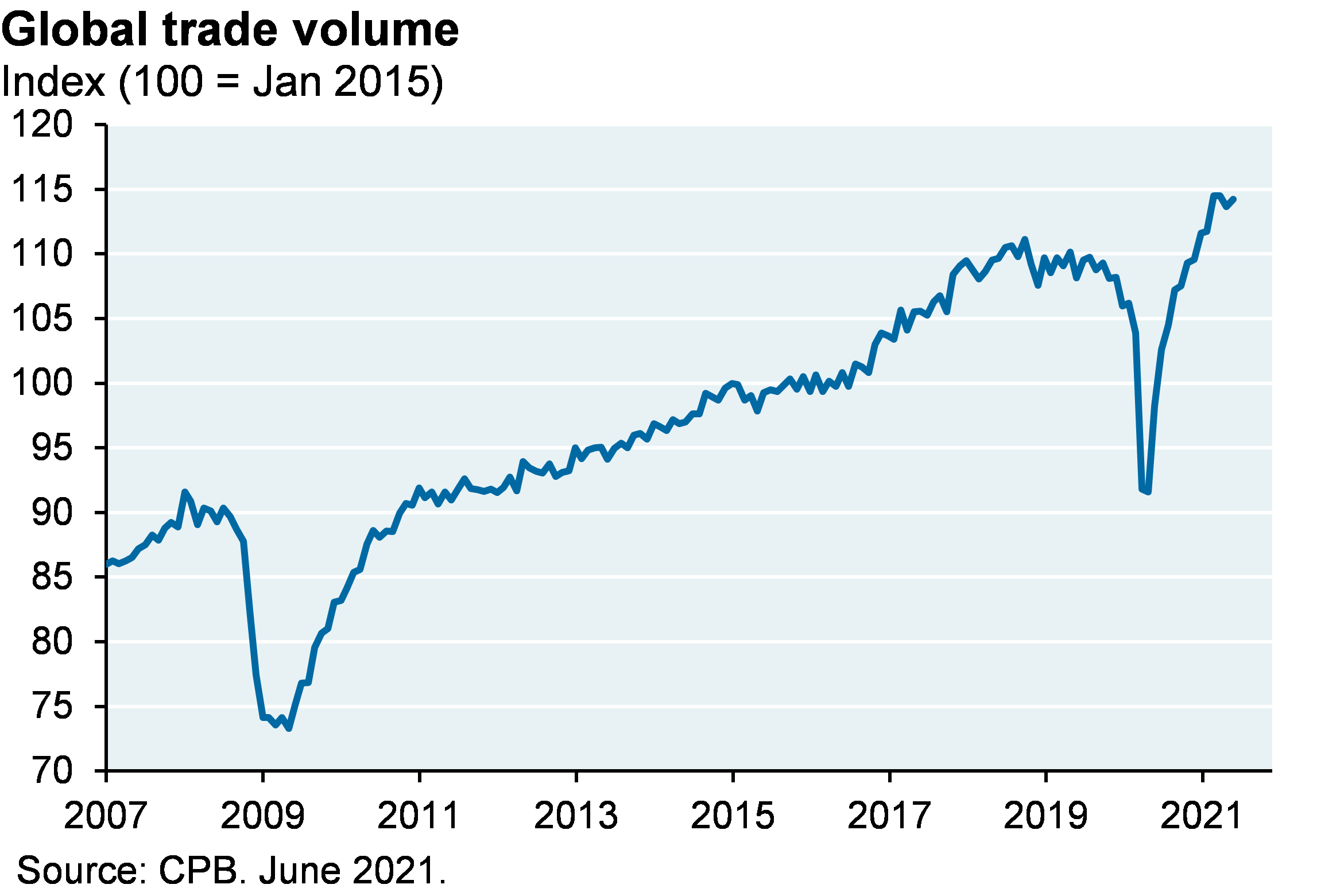

So let me get into that a little bit, and this is on page two of the piece. There was a surge in goods consumption in the United States when COVID hit, as everybody started building out home offices and doing home improvement projects, and overall just increasing their goods spending and drastically cutting back on their services spending. So all of a sudden, global trade volume started to pick up just at the time that COVID was beginning to negatively impact all the workers and the supply chains in the U.S. and Asia.

And then the shipping thing started to kick in a few months ago, and this is kind of remarkable in an odd and unfortunately very concerning way economically. There has been a giant surge in freight rates for container ships between Shanghai, from Shanghai to Los Angeles that hasn’t been matched by an increase of freight rates from Los Angeles back to Shanghai. So what has that done, is create this weird economic incentive for container ship owners to move them back to China empty to accelerate the receipt of the eastbound freight rates, instead of waiting for U.S. goods to be loaded up so they can earn the westbound freight rates as well. And so based on the latest data we’re seeing, the westbound freight rates from Los Angeles to Shanghai are below $2,000 or 40-ft. box. The eastbound ones are above 12,000. So I can see why that’s happening.

And we actually have a chart in here showing this giant increase in the container ships that are being, returning to Asia empty are now dwarfing the ones that are actually loaded. This is messing up the supply chain in a lot of understandable ways, because as U.S. goods that were destined for export don’t leave the ports, they sit there and railcars and manufacturing sites and warehouses and dock areas are occupying the space that all of those containers ships waiting to unload into the U.S., they don’t have the space to do that. So that’s one big aspect of the supply chain disruptions that have to do with these enormous shipping cost discrepancies.

And the other one, of course, is the semiconductor issue. We talked about this a little bit last time, but just to go over a little bit of again, these chip shortages are related to the older and simpler 200-mm wafers, but they’re used in everything, cars, computers, laptops, refrigerators, washing machines. These are the things that soared in terms of demand during the pandemic as people built out home offices, and the impact on auto manufacturers is kind of remarkable. We have a chart in here that looks at the surge in manufacturer inventories and the collapse in dealer inventories as they’re waiting for the chips to come in to complete those vehicles and get them out for sale.

There’s limited economic incentive for people to build these new plants because the margins are so low, and there’s only a handful of new ones planned for 2022. The good news is that there’s a few billion dollars being invested to expand capacity in the existing plants, in which case the semiconductor squeeze should start to ease a little bit by Q2 of next year. And auto manufacturers are also discussing some long-term contracts with these tier two semiconductor suppliers that might incent them to build out some new capacity kind of the way an LNG export facility works. It’s very hard to finance a multibillion dollar LNG export facility unless you’ve got pre-committed investment grade long-term contracts to help finance construction. And increasingly, we might see that required to get new semiconductor capacity built.

And for all the clients that have always mentioned to me over the years their concerns about the political and economic problems associated with the rise of autonomous vehicles and lots of unemployed and angry truckers, I always tell them they’ve got it backwards. The U.S. has had a trucker shortage for the last few years, and it’s projected to get much worse. And so what’s happened here is that COVID has worsened some of the vulnerabilities in the U.S. supply chain, just as global goods trading is surging and people want more stuff instead of services.

So how does this get resolved? This is one of the topics we spent a lot of time here on at this CEO gathering. Well, the world is going to need more containers which carry more than 90% of the world’s traded goods, right. So the world needs more of these containers. Who comes to the rescue here? Unsurprisingly, the Chinese get the benefit. The Chinese companies affiliated with the Chinese government make up, I think 95% of the world’s container production market, and they’ve ramped up production. We’re also going to need more container ships in service. Those are rising obviously more slowly. They take time to build. Who is going to benefit there? China, the world’s largest ship builder. I think they got 45% of all new shipbuilding orders in 2019. Here are some more examples of how China continues to reap some unforeseen benefits from this COVID pandemic.

But more containers and container ships aren’t going to solve the problems in the West unless some of the other supply chain issues are resolved as well that have to do with labor, and that’s probably going to require an end to extraordinary housing and income support measures and a lot less concern about COVID. So far, most of the analyses that we’ve seen don’t show a big differential in job growth between states that terminated the employment subsidies and those that didn’t. That may have to do with the fact that it hasn’t happened yet but it’s going to; it may have to do with the fact that the Delta variant is a bigger issue. We don’t know yet.

That said, most of the forecasts we see call for around one-and-a-half to two million new jobs by the end of the year, due to some combination of expiring unemployment benefits and school reopening and less concerns about COVID. So we’ll see. And then on the foreclosure moratorium, those programs are also scheduled to end this fall. Foreclosures collapsed once the moratorium was put in place, and so that’s also ending.

And so the bottom line is that U.S. and European housing and income policies may have to normalize before labor supplies do. When you look, we have a chart in here that looks at G7 manufacturing wages rising at some incredibly rapid clip at a time when unemployment rates are still this high. And then one last comment here. It is interesting that some of the people that are arguing for endless extension of the COVID unemployment benefits are also arguing for the largest amount of new Congressional spending, like 3.5 trillion.

Without circling how all of that Congressional spending, what it might do to labor shortages, where are all these new workers supposed to come from, and how might that impact inflation and Fed policy? In August, around half of all small business owners said they had job openings that they already couldn’t fill, which is the highest level on record, and that’s before people are suggesting $3.5 trillion worth of new Congressional spending.

So on the COVID side, the concerns may dissipate in the next few months. We had a client webcast in August where we laid out our vision for the fall that was heavily influenced by research we’ve done, conversations that we had with epidemiologists and chief medical officers at the vaccine companies. And what we laid out was okay, this is going to be a terrible fall in the U.S. And so far it is. The latest infection and hospitalization mortality data in the hot spot states, mostly in the Southeast, are terrible. The U.S. has the highest reported mortality rate in the world in the southeastern United States.

But we also thought that, given the high degree of Delta-contagiousness, a combination of vaccination and acquired immunity would drive down these pandemic measures substantially by, let’s call it November. It looks like we’re still on track there. We’ve got a chart in here showing a pretty sharp rollover in infections and hospitalizations in the Southeast. Mortality is still rising, and it is a terrible rate and all the things you read about the ICU are true, but given the lag times between infection, hospitalization, and mortality, you would expect the death situation to get a lot better in the next few weeks as well.

The biggest look to this outlook is the fading immunity of vaccinated people. We just don’t have enough information on this yet. We’ll know more over the next few months how this plays out. It is clear that the booster shots in Israel are driving antibody levels up substantially. And for all the people concerned about Pfizer’s very modest efficacy gap versus Modena, the booster shots in Israel are showing that the efficacy numbers for Pfizer go back well above 90%, which is where the Moderna numbers are. So if you’re concerned about that gap, go get a booster shot.

The developing world situation is a little more nuanced. First of all, infections and mortality are declining. This is mostly the result of the exhaustion of the lambda and gamma variants in Latin America and the delta variant in Asia. A lot of these countries have very high COVID stringency requirements, more so than, even more so than countries in the U.S. and Europe. That said, they don’t appear to be the epicenter of supply chain problems, because when we look at the data on manufacturing delivery time delays, the data is much worse for the Euro zone and the U.S. than it is for India, China, South Korea, and Brazil. We know that in places like Malaysia that there are some issues around semiconductors and other stuff, but most of the supply chain issues appeared to be developed market problems, and that’s why some combination of reduced COVID concern and income and policy, income and housing support policy normalization are going to be required to resolve this.

So when does that happen? I think both of those things happen over the next few months, and we start to see an easing of supply chains in Q1 of next year, although I will say that based on the CEOs in attendance at this event, they were more thinking Q3 and Q4 of next year. So we’ll see how that plays out, and we’ll update you in the future as to whether they were right or I was right. Anyway, thanks for listening, and we’ll talk to you next time, bye.

FEMALE VOICE: Michael Cembalest’s Eye on the Market offers a unique perspective on the economy, current events, markets, and investment portfolios, and is a production of JP Morgan Asset and Wealth Management. Michael Cembalest is the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy for JP Morgan Asset Management and is one of our most renowned and provocative speakers. For more information, please subscribe to the Eye on the Market by contacting your JP Morgan representative. If you’d like to hear more, please explore episodes on iTunes or on our website.

This podcast is intended for informational purposes only and is a communication on behalf of JP Morgan Institutional Investments Incorporated. Views may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as personal investment advice or a solicitation or recommendation. Outlooks and past performance are never guarantees of future results. This is not investment research. Please read other important information which can be found at www.JPMorgan.com/disclaimer-EOTM.