Election overview

-

What are the key dates for the 2024 election?

2024 Election Landscape

-

What’s at stake in the Electoral College and Congress?

2024 Election Landscape

-

What are the implications on debt and deficits?

Policy

-

How should investors approach investing in an election year?

Investing in an election year

-

How volatile are markets during an election year?

Investing in an election year

-

How do returns look under different configurations of government?

Investing in an election year

-

What configuration of government is best for the economy and markets?

Investing in an election year

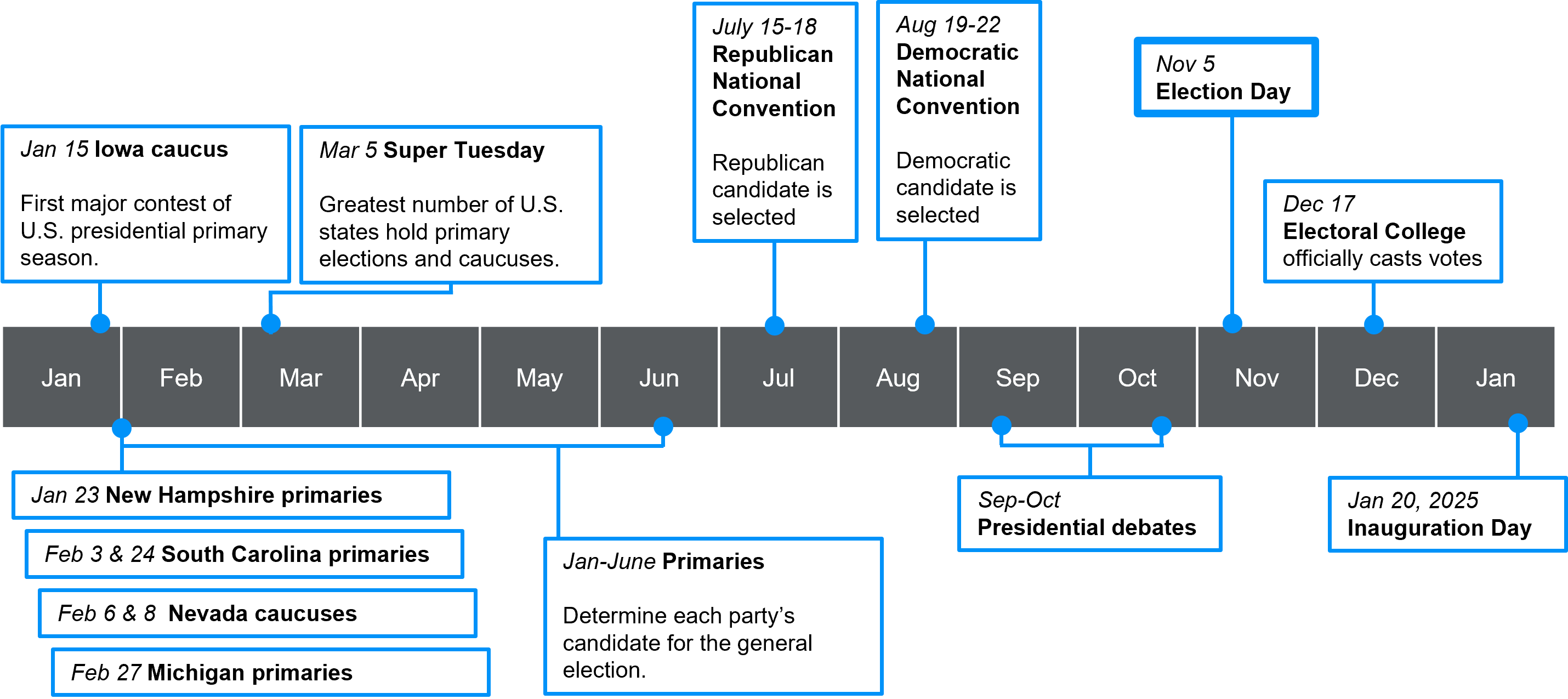

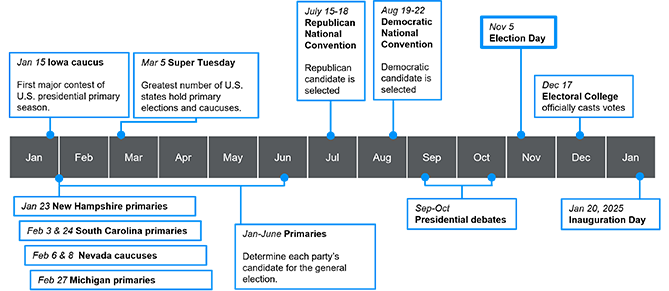

What are the key dates for the 2024 election?

The 2024 election officially kicks off in mid-January with the Iowa caucus, followed by the other early contests in New Hampshire, South Carolina, Nevada and Michigan. The single biggest day of primary season is Super Tuesday on March 5, when the greatest number of states hold primary elections and caucuses. Shortly after Super Tuesday, the leading candidates will likely be well established, although primaries do not conclude until June. During the summer, Republicans and Democrats will hold their national conventions, which officially nominate the presidential and vice-presidential candidates for their respective parties, and each party establishes its party platform. In the fall, campaigning heats up and presidential debates are held. Finally, on Tuesday, November 5, 2024, the election is held. The Electoral College then officially casts its votes on December 17, and the new administration is inaugurated on January 20, 2025.

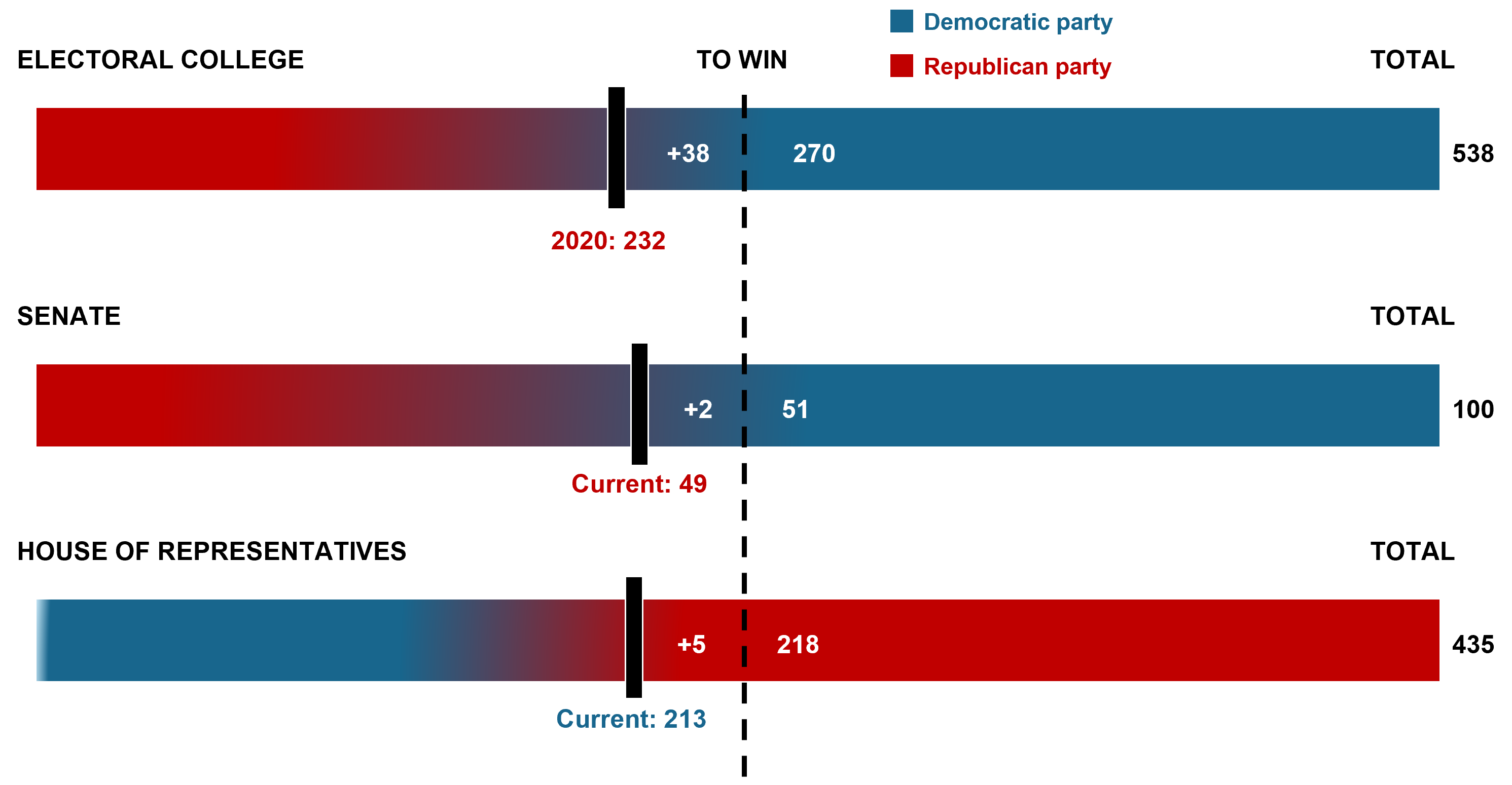

What’s at stake in the Electoral College and Congress?

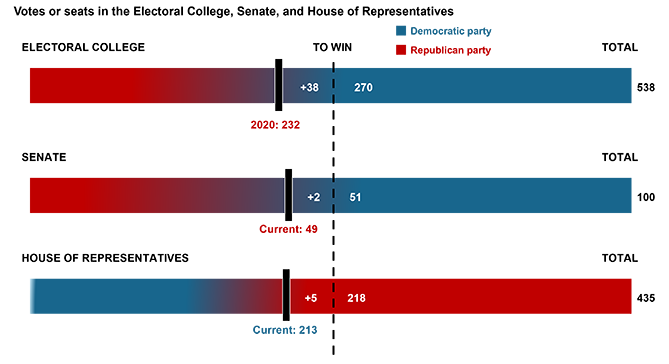

The presidential race will captivate voters most, but critical to a president’s success in implementing their agenda is the configuration of Congress, comprised of the Senate and House of Representatives. Here is what’s at stake, and the paths to victory for each:

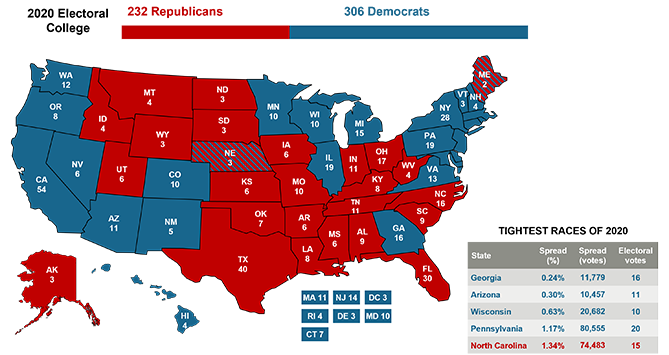

Electoral College

There are 538 electoral college votes available, and 270 are required to win. In 2020, President Biden earned 306 votes and former President Trump earned 232 votes. Therefore, the Republican candidate would need to pick up 38 votes relative to 2020. Although 38 votes may seem like a significant pick-up, in 2020, three states (GA, AZ, WI) accounting for 37 electoral college votes were determined by under 43,000 individual votes. Several races were called days after the election, and five races had less than a 2% spread of votes between candidates – GA, AZ, WI, PA (won by Biden) and NC (won by Trump). Those states, along with Nevada, Michigan and Florida, will likely determine the next president of the United States.

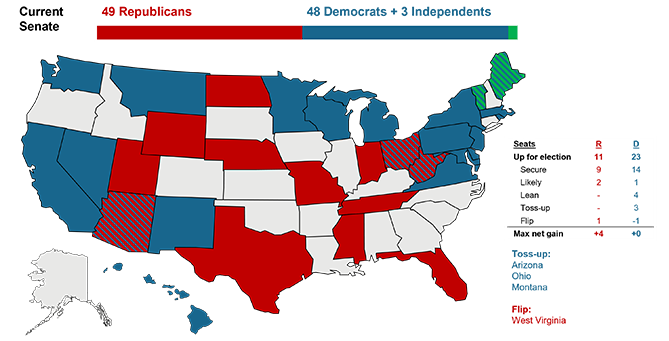

Senate

There are 100 seats in the Senate and Senators serve staggered 6-year terms, so every two years, about one-third of the Senate is up for election. The Senate currently consists of 48 Democrats, 49 Republicans and 3 Independents that typically vote with the Democrats (ME, AZ, VT). In 2024, 34 seats are up for election, 23 currently held by Democrats and 11 held by Republicans. According to The Cook Political Report, there are three toss-up states, all currently held by Democrats: Arizona, held by Kyrsten Sinema (who was elected as a Democrat but became an Independent); Ohio, held by Sherrod Brown; and Montana, held by Jon Tester. Democratic Senator Joe Manchin of West Virginia will not run again, so that seat is very likely to flip to the Republican party. The Republicans need two seats to control the Senate, or just one if they also win the White House as the vice president casts tie-breaking votes. Therefore, there is not much ground for Democrats to gain, and they are at risk of losing their slim majority.

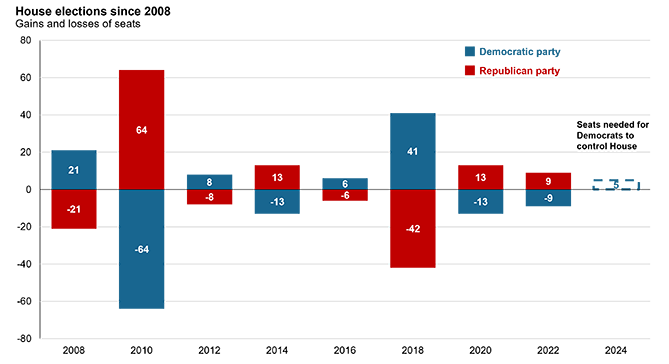

House of Representatives

All 435 seats in the House of Representatives are up for election every two years. The House currently consists of 221 Republicans, 213 Democrats, and 1 vacant seat (formerly held by a Republican). The Democrats would need to win 5 seats to take control of the House.

Votes or seats in the Electoral College, Senate, and House of Representatives

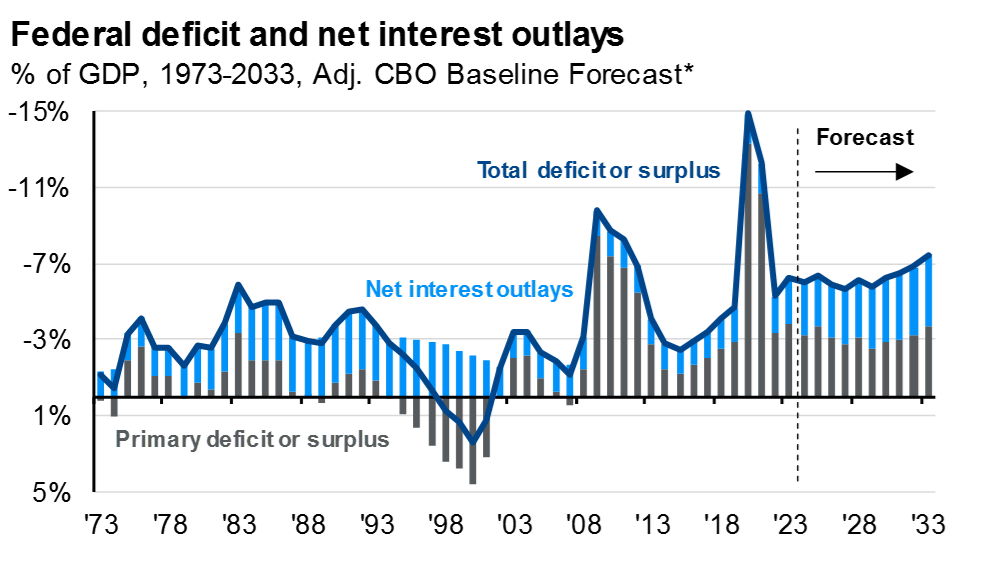

What are the implications on debt and deficits?

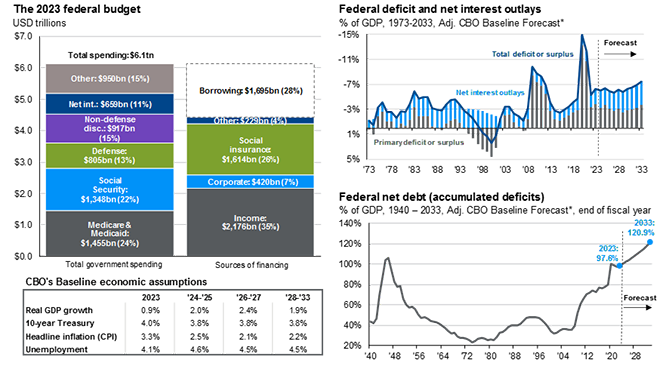

In the long run, it is policy, not politics, that matters most for the economy and markets. One critical topic that is likely to inspire heated debate is federal finances, particularly as fiscal fears contributed to driving bond yields higher in 2023.

The federal budget deficit was $1.7 trillion in 2023, or 6.3% of GDP, exceeding the 50-year average of 3.7%. This includes a $333 billion deficit reduction in fiscal year 2023 from student debt forgiveness that increased the deficit in 2022 but was later struck down by the Supreme Court in June 2023. Without this accounting adjustment, the budget deficit would have exceeded $2 trillion or 7.5% of GDP. This compares to a deficit of $1.4 trillion in 2022, or 5.4% of GDP, which does include the outlay for student loan forgiveness that was never spent. Prior to the pandemic, the deficit did not exceed $1 trillion and the deficit as a share of GDP was 3.8% in 2018 and 4.6% in 2019. Looking ahead, the Congressional Budget Office projects that deficits will be 5-7% annually over the next decade. This is likely to send U.S. debt to GDP well above 100% over the next decade.

Not only is the deficit historically high, but new borrowing is being financed at much higher rates after the Federal Reserve raised policy rates by 5.25%. Therefore, net interest payments on outstanding debt will be a large contributor to the deficit going forward. Net interest payments reached $659 billion in 2023, up from $413 billion in 2021 before the Federal Reserve began hiking rates.

While the political solutions are clear – raising taxes and cutting spending – the political will to do either will be limited. A Democratic president may be willing to let the 2017 tax cuts sunset at least partially at the end of 2025 but may expand spending. A Republican president may look to cut spending, but would likely extend the 2017 tax cuts, and perhaps propose new tax cuts. Of course, a president’s ability to pass any proposals into law would depend on the makeup of Congress. However, the net effect of either of these paths is unlikely to reduce the deficit from the trajectory it’s on.

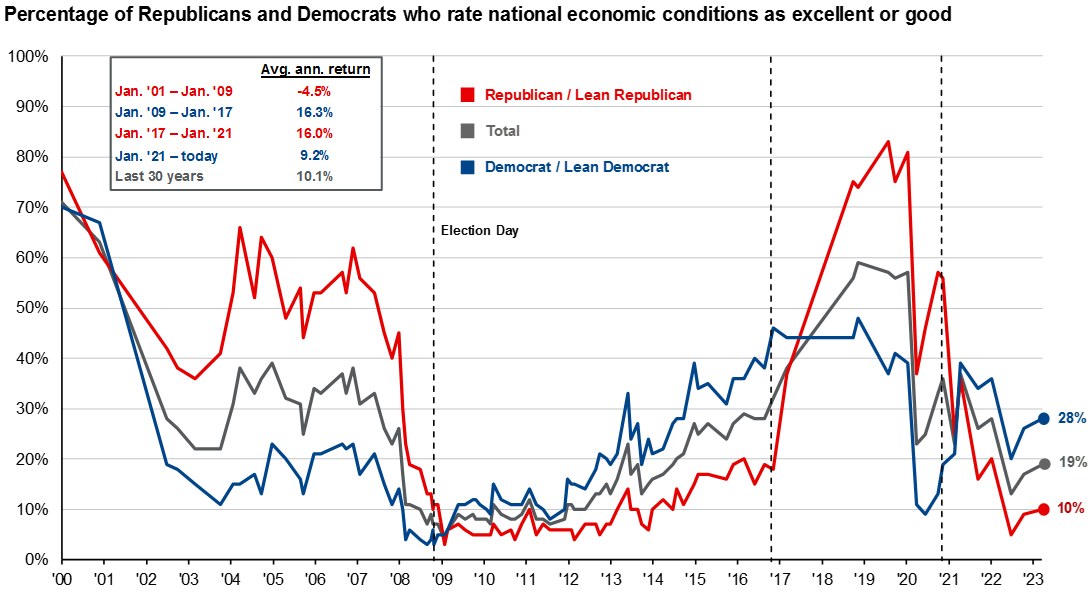

How should investors approach investing in an election year?

Political opinions are best expressed at the polls, not in a portfolio. One cardinal rule investors ought to follow: Don’t let how you feel about politics overrule how you think about investing.

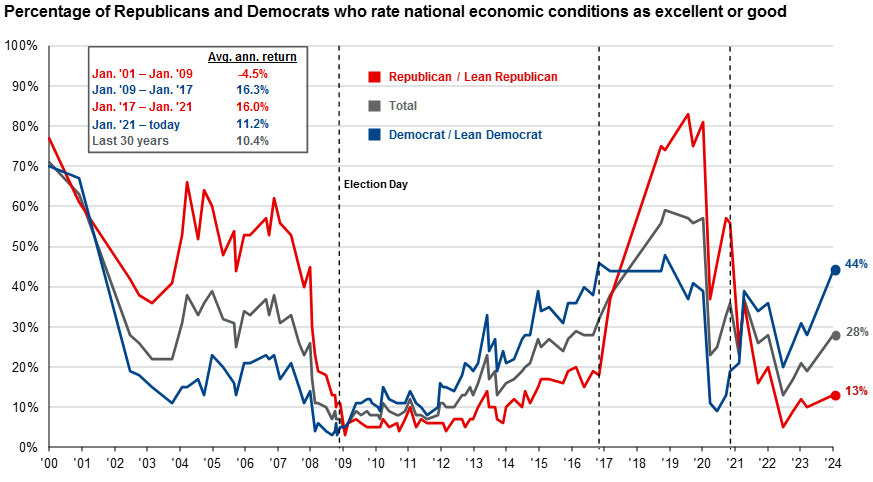

The chart below shows a survey from the Pew Research Center asking Americans how they feel about economic conditions. The results show that Republicans often feel better about the economy under a Republican president, while similarly Democrats often feel better about the economy under a Democratic president. Investors often make portfolio decisions based on their economic outlook.

Yet, average annual returns on the S&P 500 during the Obama administration of 16.3% and during the Trump administration of 16.0% were almost identical and higher than the average return over the last 30 years of 10.1%. It is likely the macro conditions, like ultra-low interest rates enjoyed during both Obama and Trump administrations, were a more influential driver of above-average returns during those periods, rather than the policy prescriptions each president espoused.

Investors who allowed their political opinions to overrule their investing discipline may have missed out on above-average returns during political administrations they didn’t like.

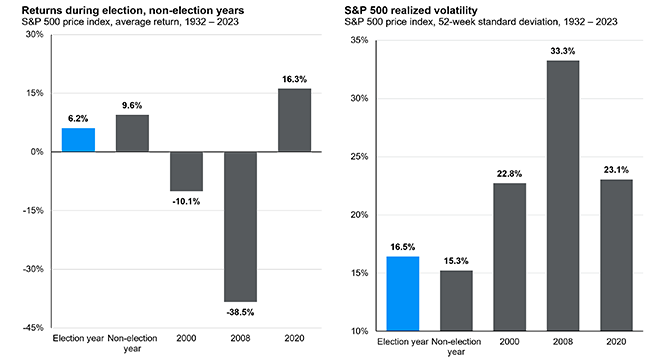

How volatile are markets during an election year?

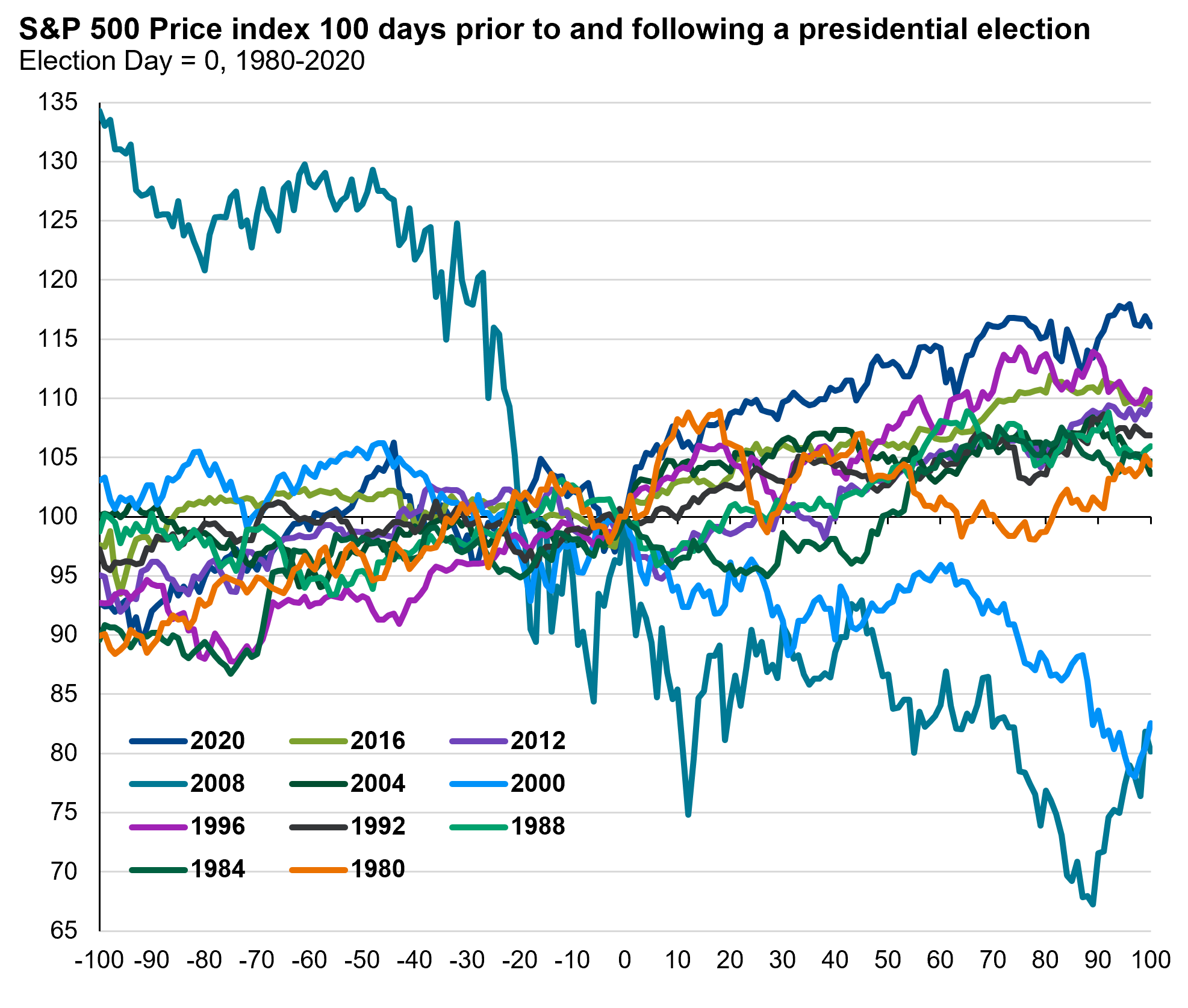

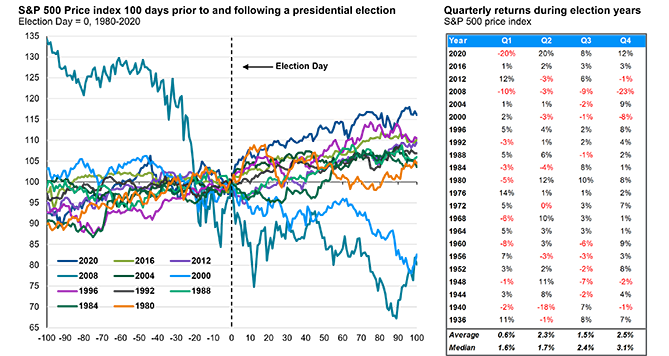

During election years, returns tend to be lower and volatility tends to be higher because markets do not like uncertainty and elections breed uncertainty. Since 1932, S&P 500 returns on average were 6.2% during election years vs. 9.6% during non-election years. Realized volatility was 16.5% during election years and 15.3% during non-election years. The average market drawdown in a given calendar year since 1980 was 14.2%, but 16.3% in election years vs. 13.5% in non-election years.

However, averages don’t tell the full story as recent presidential election years have been particularly volatile with historic market drawdowns. For example, the 2000 sell-off was related to the bursting of the tech bubble, 2008 was the onset of the financial crisis, and 2020 was the onset of the pandemic. 2020 experienced a sharp correction and then a strong rebound, both completely unrelated to the election.

As highlighted in the chart below, markets tend to be more volatile in the lead-up to the election, but after election day, that source of uncertainty is cleared, and, regardless of the result, markets move on and refocus on the fundamentals. In fact, median returns in the first three quarters of an election year were 1.9% compared to 3.1% in the fourth quarter going back to 1936.

This was the case in almost all presidential elections since 1980, with two notable exceptions in 2000 and 2008. The fourth quarter of 2008 was the unfurling of the financial crisis, but it should be acknowledged that in 2000, in addition to tech bubble-related headwinds, uncertainty around the fate of the election did cause market jitters. In the presidential election of 2000, we did not get official election results until a Supreme Court ruling on December 12, 2000. The S&P 500 fell by 4.2% between the election and that ruling. In contrast, markets were up 7.3% the week of the 2020 election despite not having an official result until the following Saturday.

That is why market timing can be a dangerous strategy around elections. The two most recent presidential elections in 2016 and 2020 are prime examples of this. In the early hours of November 9, 2016, futures plummeted as election results were coming in, but markets closed 1.1% higher after that day’s regular trading session when the results were finalized, and as mentioned, markets rallied strongly after the 2020 election. In fact, in both cases there was a pre-election rally of 3% between the prior Friday and election day itself, so markets turned before many ballots were even cast. Some investors are eager to sit on the sidelines until election uncertainty passes, but risk missing subsequent rebounds which typically occur faster than investors can get back into the market.

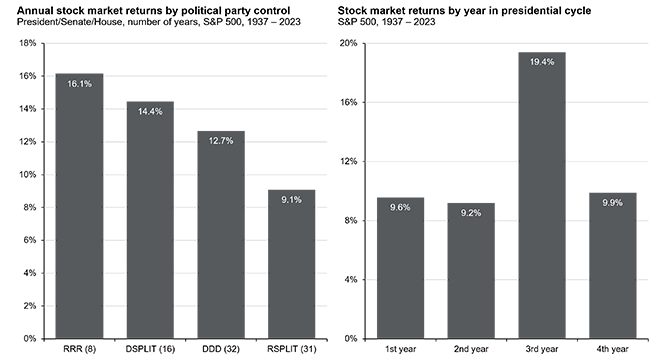

How do returns look under different configurations of government?

Investors always want to know how markets performed under different configurations of government or different years of a presidency. How do markets perform under a Republican sweep or Democrat sweep? What if a Republican wins the White House but loses both chambers of Congress? How do returns look in the first year of a presidency?

This information is relatively easy to compute but these returns tell investors very little about why markets performed the way they did and how markets are likely to perform in the future. Monetary policy, fiscal policy, economic growth, labor markets, corporate profits and valuations are much better indications of future returns. Fiscal policy is driven by the government of course, but the configuration of the government matters and a sweep by one party doesn’t guarantee that it will accomplish all its campaign promises. In fact, due to growing political polarization, garnering consensus within a party is becoming increasingly difficult. For example, while the Democrats controlled Congress, President Biden had an ambitious Build Back Better proposal, which was later scaled down to a more moderate Inflation Reduction Act as a compromise between members of his own party.

Furthermore, just as calendar years are arbitrary markers when considering economic and market cycles, they also seldom align with actions of presidential administrations.

The economic context, not the political context, tends to be much more relevant to understanding historical market environments and returns.

What configuration of government is best for the economy and markets?

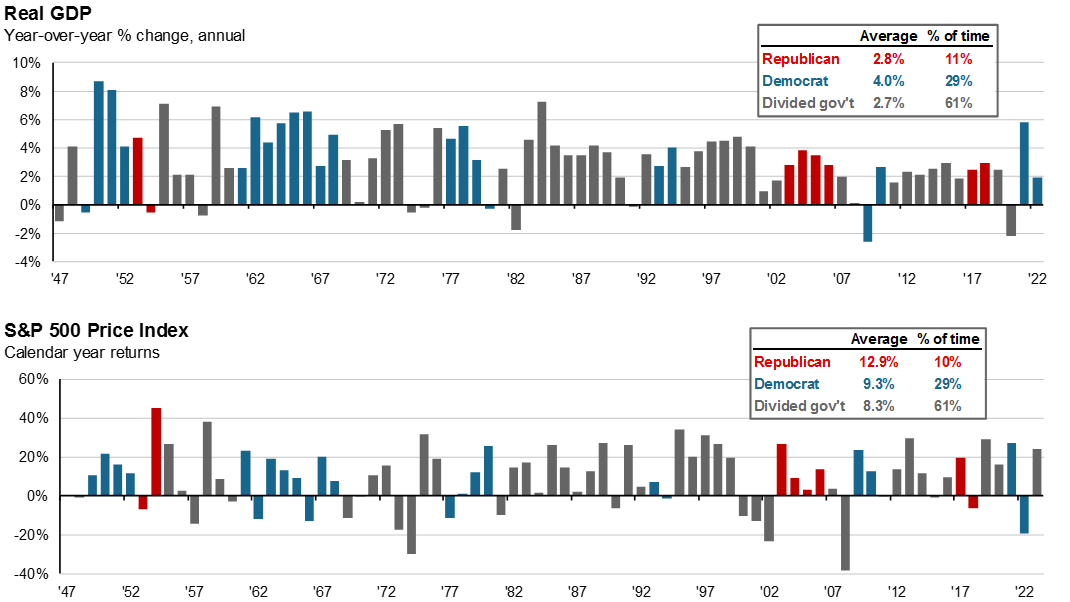

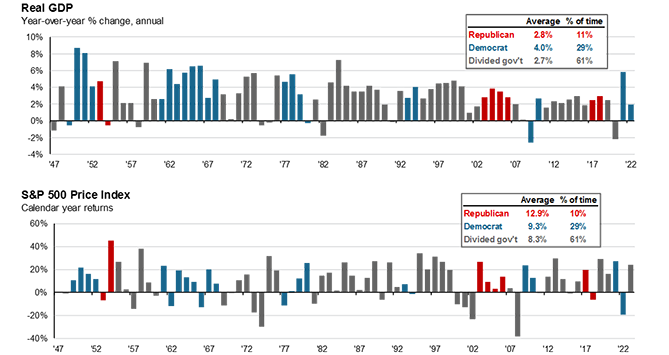

As highlighted in a prior post, looking at returns during different government configurations tells investors little about why markets or the economy performed the way they did, and give little indication of how this could play out in the future.

The charts below highlight real GDP growth and S&P 500 returns during Republican (red), Democratic (blue), and divided governments (when one party does not control the White House and both chambers of Congress). Since 1947, real GDP has grown on average 2.8% under Republican rule and 4.0% under Democratic rule. The S&P 500 has returned 12.9% under Republicans and 9.3% under Democrats.

It would be easy to conclude that the economy performs better under Democrats and the market performs better under Republicans, but the sample sizes are relatively small. Republicans have controlled the government only 11% of the time since World War II, in the mid-1950s, early 2000s, and just before the pandemic. These were significantly disparate macro environments. Democrats have controlled the government 29% of the time, mostly in the post-WWII period and in the 1960s, but only in six years over the past three decades. Instead, the most common configuration of government is divided, which has produced 2.7% annualized real GDP growth since World War II, and 8.3% annualized returns on the S&P 500.

Ultimately, both the economy and markets tend to fare well under most government configurations.

Latest Insights

2024 Election presentation

The information presented is not intended to be making value judgments on the preferred outcome of any government decision or political election.