Many investors see today’s supply chain disruption as a consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic and high inflation. However, supply chain issues have been evident for much longer. From Brexit and President Trump’s trade wars to the war in Ukraine, companies have been facing a relentless series of stress tests on the way they manufacture and ship goods.

Central to the new supply chain dynamics are environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Whether companies are outsourcing more elements of their manufacturing or trying to localise their production, there are ESG issues to be addressed right across modern supply chains. As investors, we need to challenge companies to address the key ESG considerations within their supply network.

Outsourcing and localisation

Originally, companies outsourced production to Asia, and China in particular, to reduce labour costs. However, cost reduction is no longer the only factor in the outsourcing decision. Increasingly, companies are also attracted by the ability to get their production closer to the end consumer.

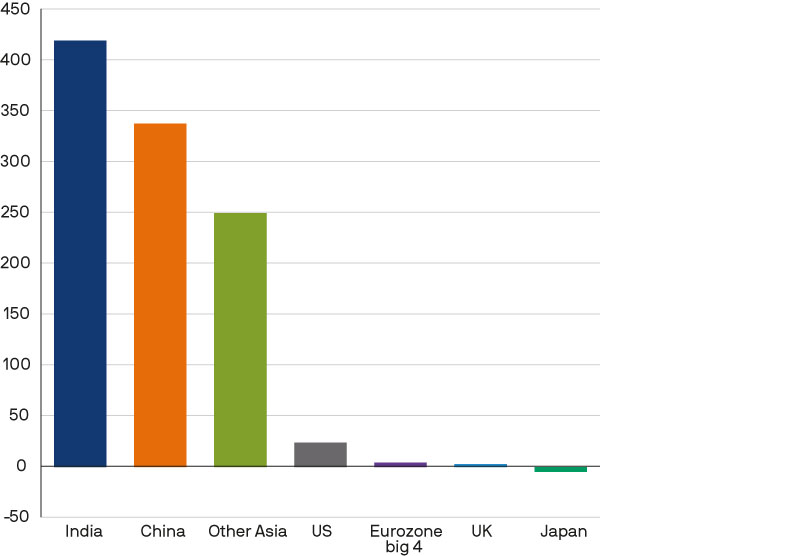

Estimated change in the 'consumer class' by 2030

Millions of people

Source: Brookings Institute J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Change in ‘consumer class’ is the change in the number of people from 2020 to 2030 living in a household and spending at least USD 11 per day per person. Other Asia includes Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan, Philippines and Vietnam. Eurozone big 4 includes France, Germany, Italy and Spain. Guide to the Markets – UK. Data as of 31 March 2022.

Sporting goods companies in Europe and the US, for example, are reliant on China as their biggest market and therefore it makes sense to stay close to the end consumer by keeping production in Asia. Chinese consumers are now powerful global consumers in their own right.

Nevertheless, companies still have a close eye on costs. With China and many other parts of Asia becoming more costly and complex places to do business as economies develop and governments look to improve conditions for workers, companies have started to move production to Asian countries with lower labour costs, such as Bangladesh. This change has introduced increased social risk for investors, as companies swap the known supply chain risks of one market for the opaque supply chains of another.

This is not to say that staying close to home means that ESG concerns disappear. For example, Online retailer Boohoo.com operated factories in Leicester that had significant social and governance issues, due in large part to poor labour conditions. The company had attempted to localise its production but continue to keep costs low, appearing to neglect worker welfare in the process.

Through engagement, investors need to ensure all companies are tracking what is happening in their supply chains and avoiding potential issues, such as forced labour.

The need to diversify and innovate

In the current challenging global economic environment, only the most resilient companies will thrive. As a result, many companies are trying to innovate to build resiliency into their supply chains. Nowhere is this innovation needed more than in the technology sector.

In the semiconductor industry, there is a clear division between Europe and the US, where the bulk of research and development takes place, and Asia, where most wafer fabrication takes place. Due to the complexity, costs and divisions of talent in the manufacturing process, self-sufficiency in semiconductor production is close to impossible, leaving areas of the supply chain highly exposed to geopolitical, environmental and social issues.

80% of semiconductor chip manufacturing is in South Korea and Taiwan, which, if you’re thinking of resiliency, could quickly become a source of risk. The semiconductor industry also faces a number of ESG issues, not least the environmental costs of a manufacturing process where the front end of the product is made in the US and Europe and then shipped back to Asia.

With today’s supply-chain disruption, the “just-in-time” models that many industries rely on have been tested to the limits. Now it’s all about “just in case”. Good governance in supply chains is no longer about running lean inventories, but instead ensuring that companies can find ways to limit overexposure to any one area of downstream production.

Many companies are embracing digitalisation to reduce complexity. Different parts of the supply chain can share information easily and even use 3D printing to reduce the back and forth of shipments. Others are building capacity. Intel, for example, aims to invest $80 billion over the next 10 years to build up capacity in the US and Europe. Meanwhile, agricultural machinery manufacturer Deere is embracing multi-sourcing, and investing in technology to better monitor and manage its supply chain.

The companies above are shown for illustrative purposes only. Their inclusion should not be interpreted as a recommendation to buy or sell.

In conclusion

While companies diversify, localise and innovate to build resilience, they must ensure they are maintaining first-rate ESG practises in their supply chains. In a world beset by trade wars, geopolitical tensions and an ongoing pandemic, it is vital that investors can keep up with any ESG issues in global supply chains.

To be able to study supply chains effectively requires rigorous fundamental bottom-up research, as well as extensive engagement with company managements, suppliers and national authorities. Engagement should include visits to different parts of the supply chain to ensure monitoring is sufficient and good governance is maintained. Top-down industry scores cannot capture the necessary nuance to give investors a firm grip on corporate behaviour.

Through engagement, we believe we can find many attractive companies that can maintain high ESG standards as they deal with supply disruptions, while innovating and transforming their supply chains to unlock competitive advantages.