Reruns: how equity declines precede the fall in earnings, growth and employment during recessions; new US semiconductor export policies on China and the clash of empires; and another press article extolling the renewable energy virtues of a country with little relevance for anyone else

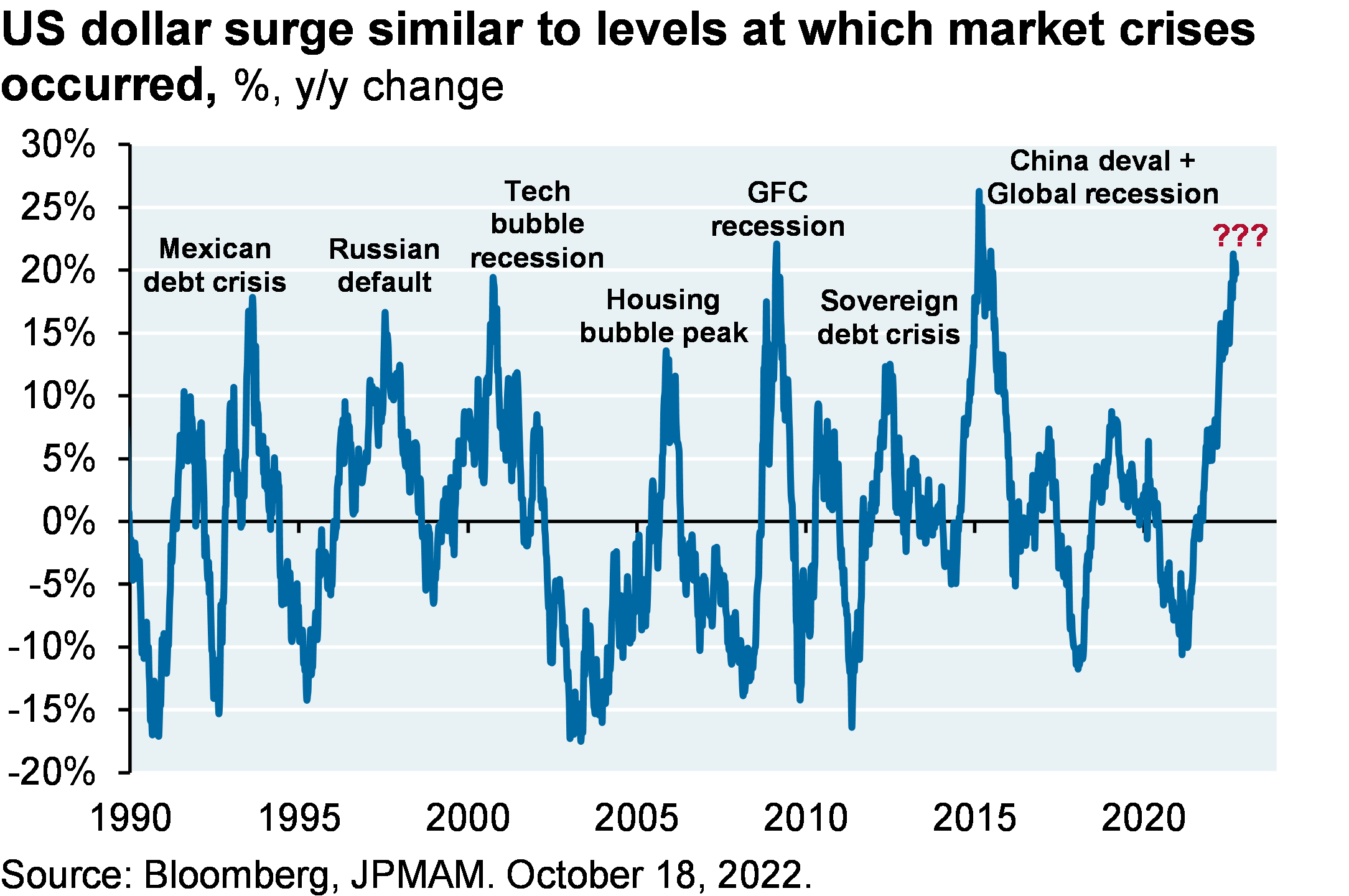

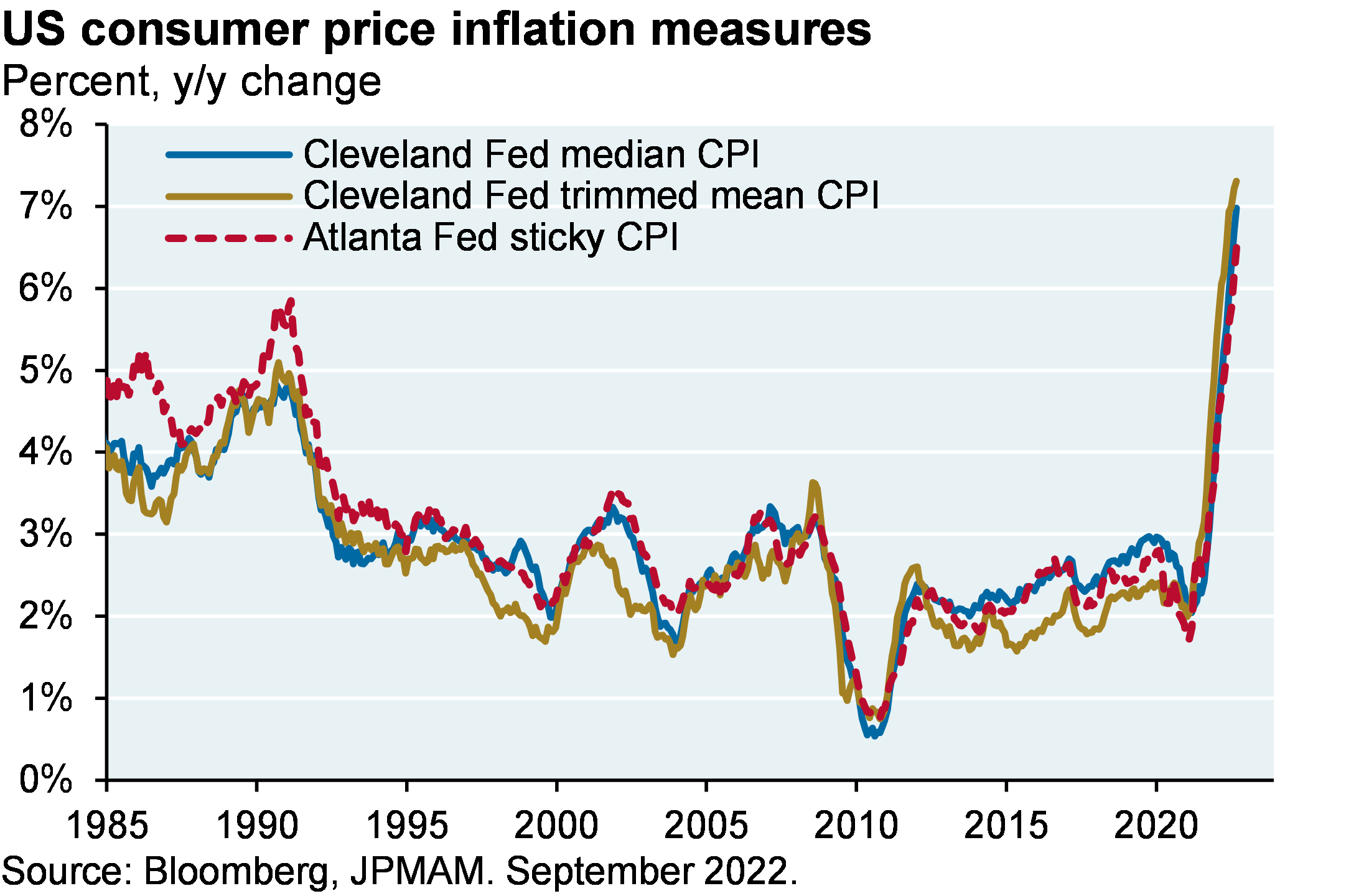

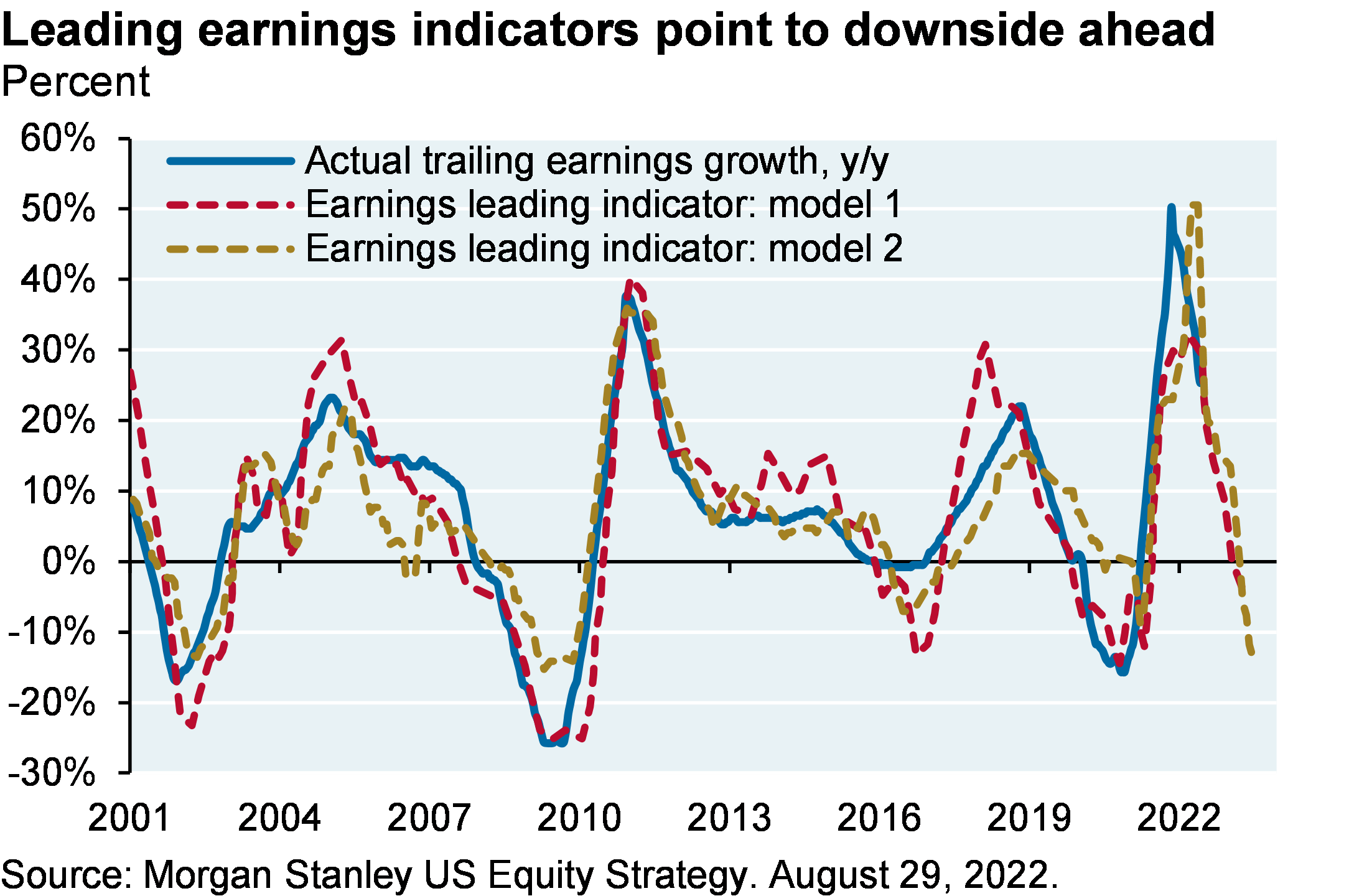

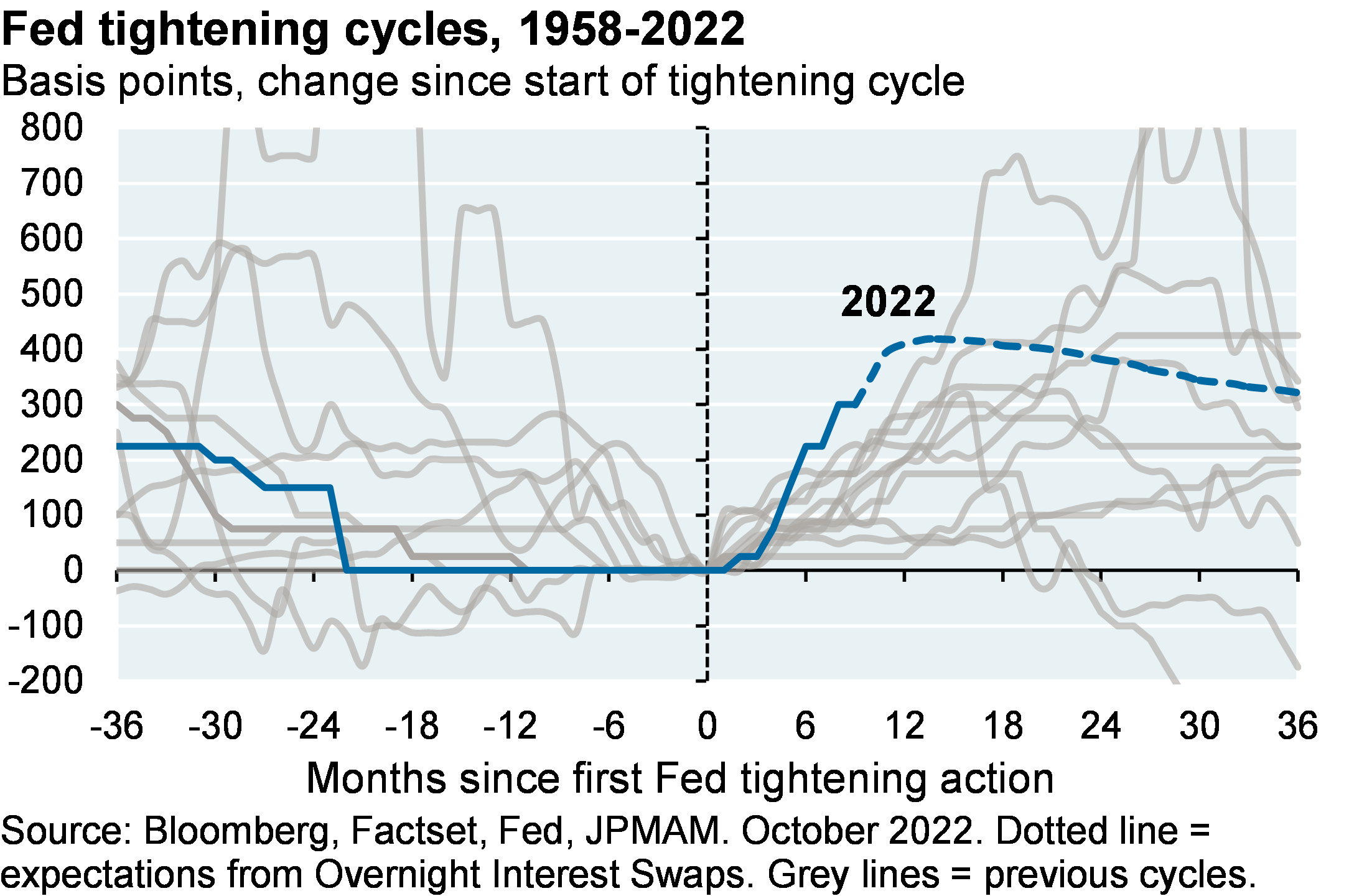

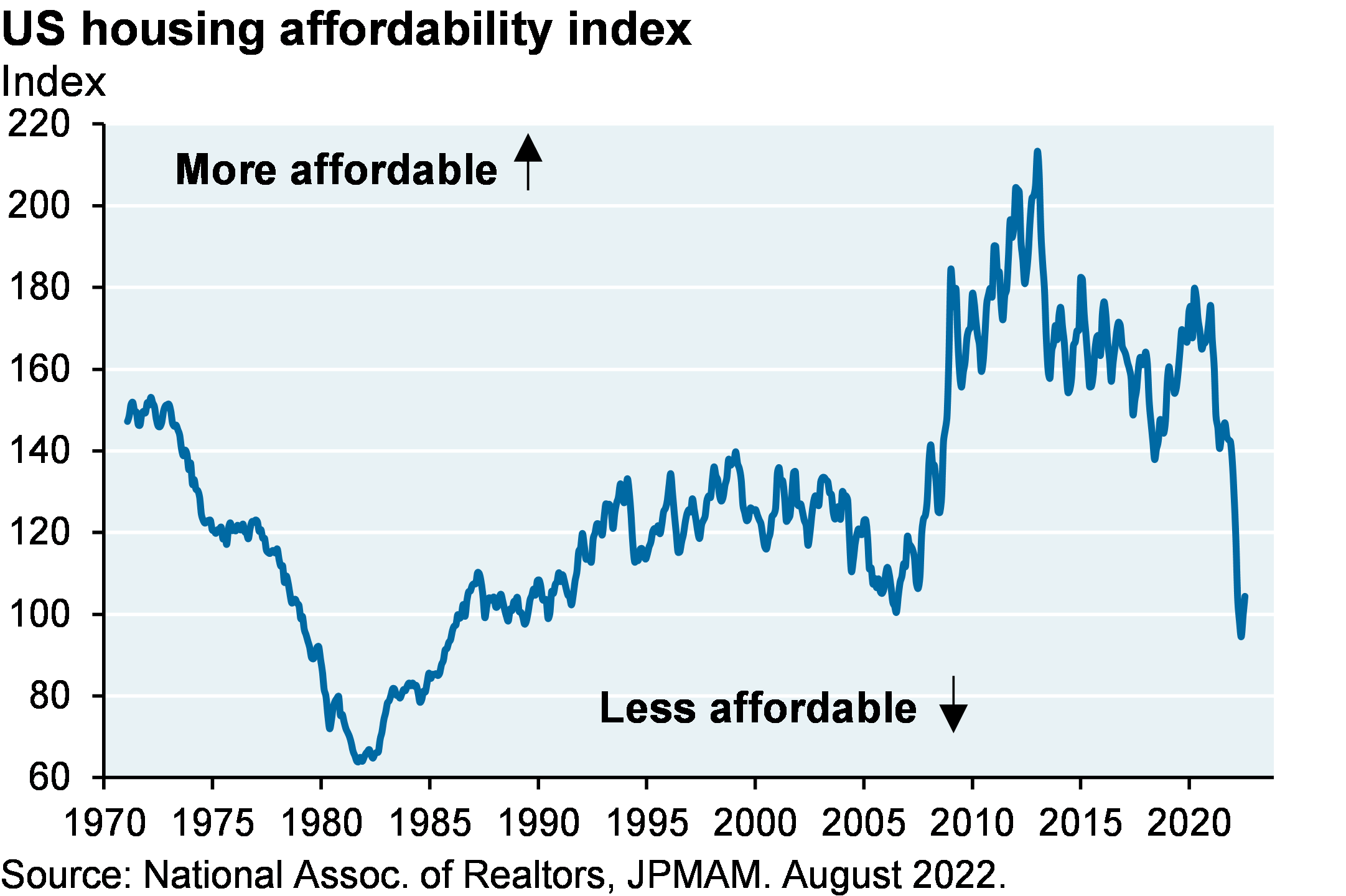

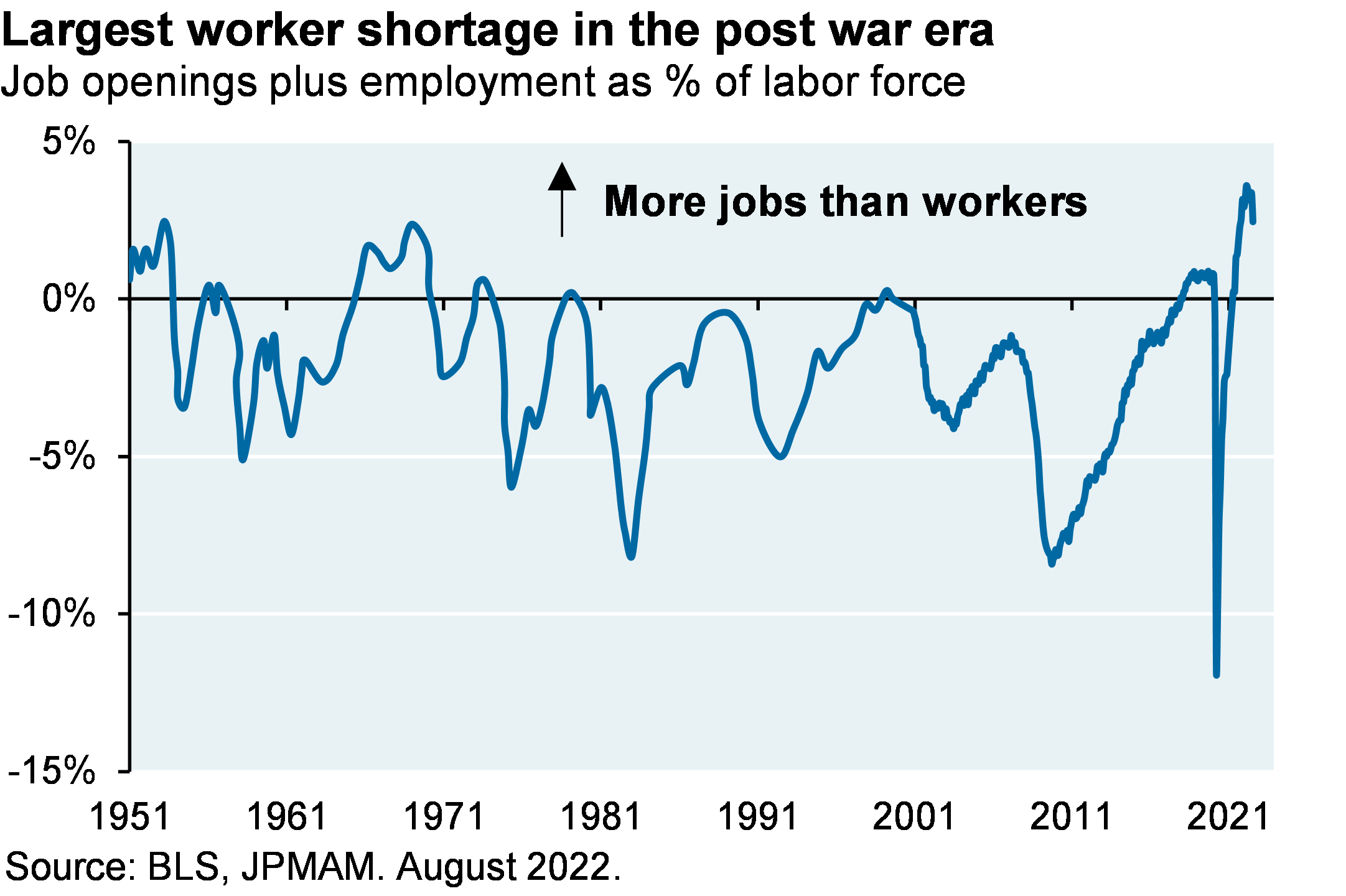

Reruns. When bear markets occur and the investment mistakes of the prior cycle are revealed, bearish investment commentary tends to intensify. There is a confessional, self-flagellating quality to some of this research, as if its authors are trying to atone for having missed the signals and risks during the prior boom. I read around 1,500 pages of research each week and the most consistent message now is a litany of gloom on earnings, valuations, wage and price inflation, Central Bank policy normalization, housing, trade, energy, the surge in the US$, China COVID policy, etc. I am not saying that these things are not important, since of course they are (see Appendix charts). But for investors, there is a remarkable consistency to the patterns shown below: equities tend to bottom several months (at least) before the rest of the victims of a recession.

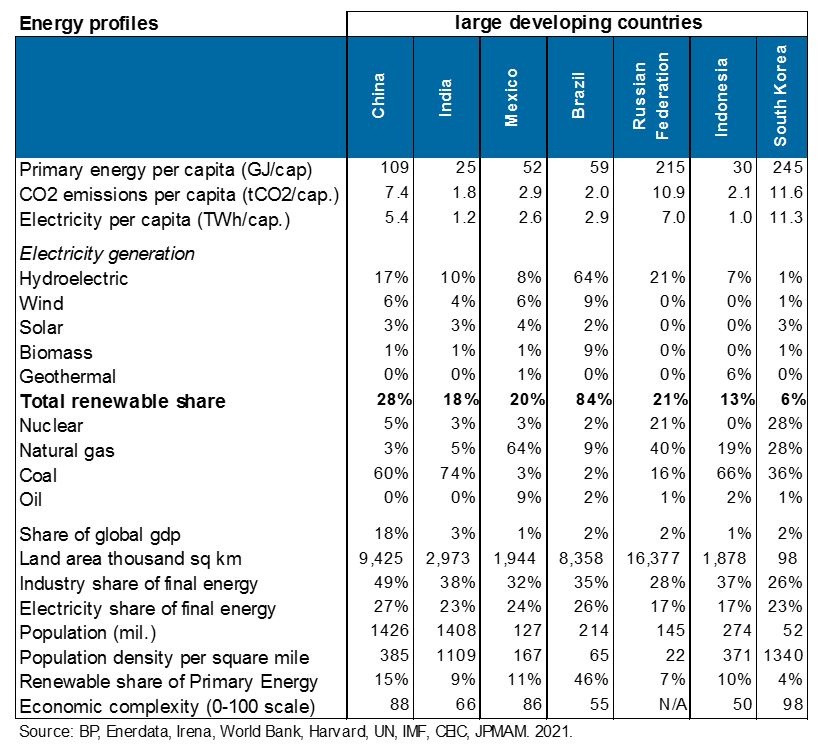

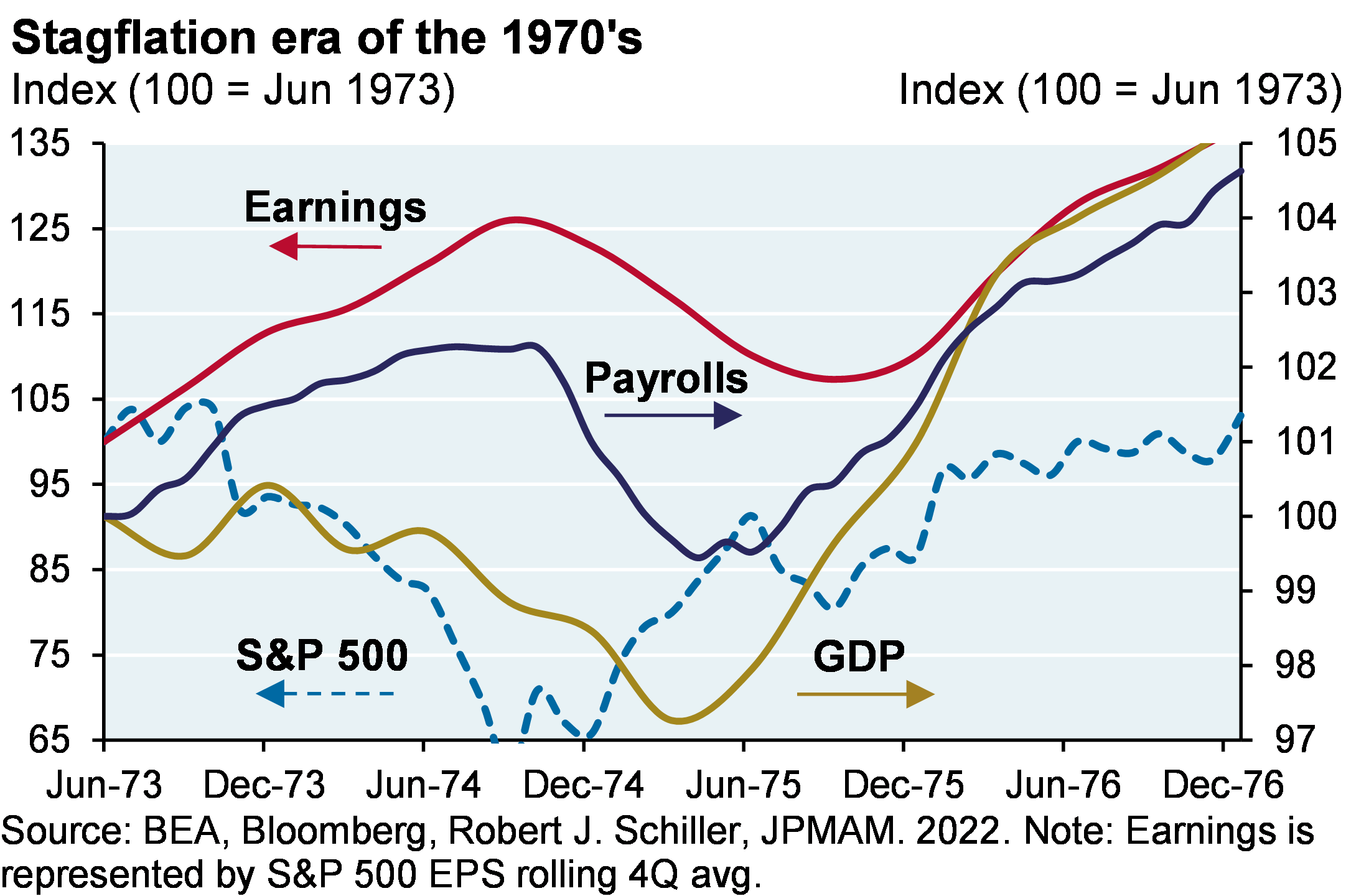

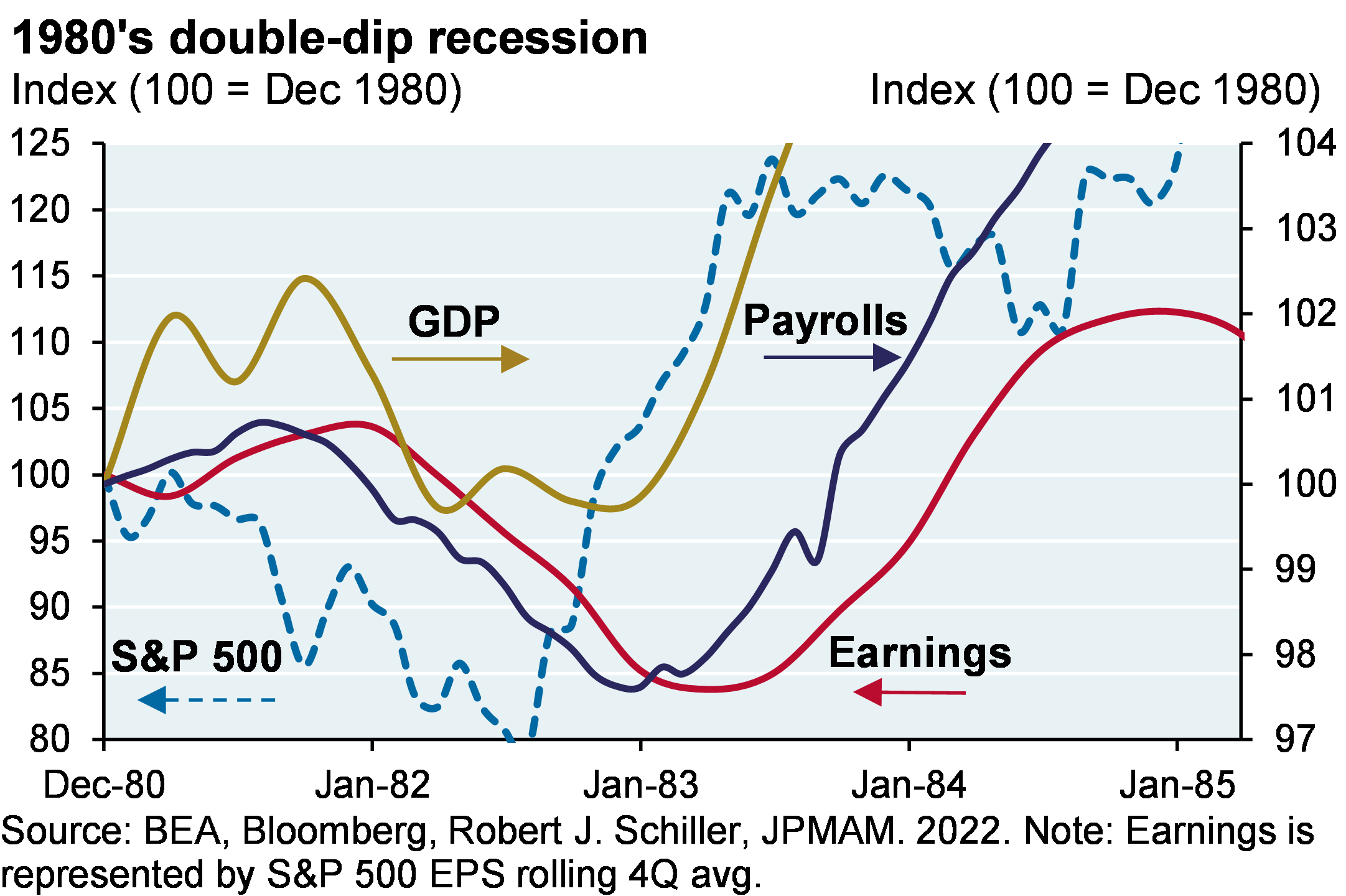

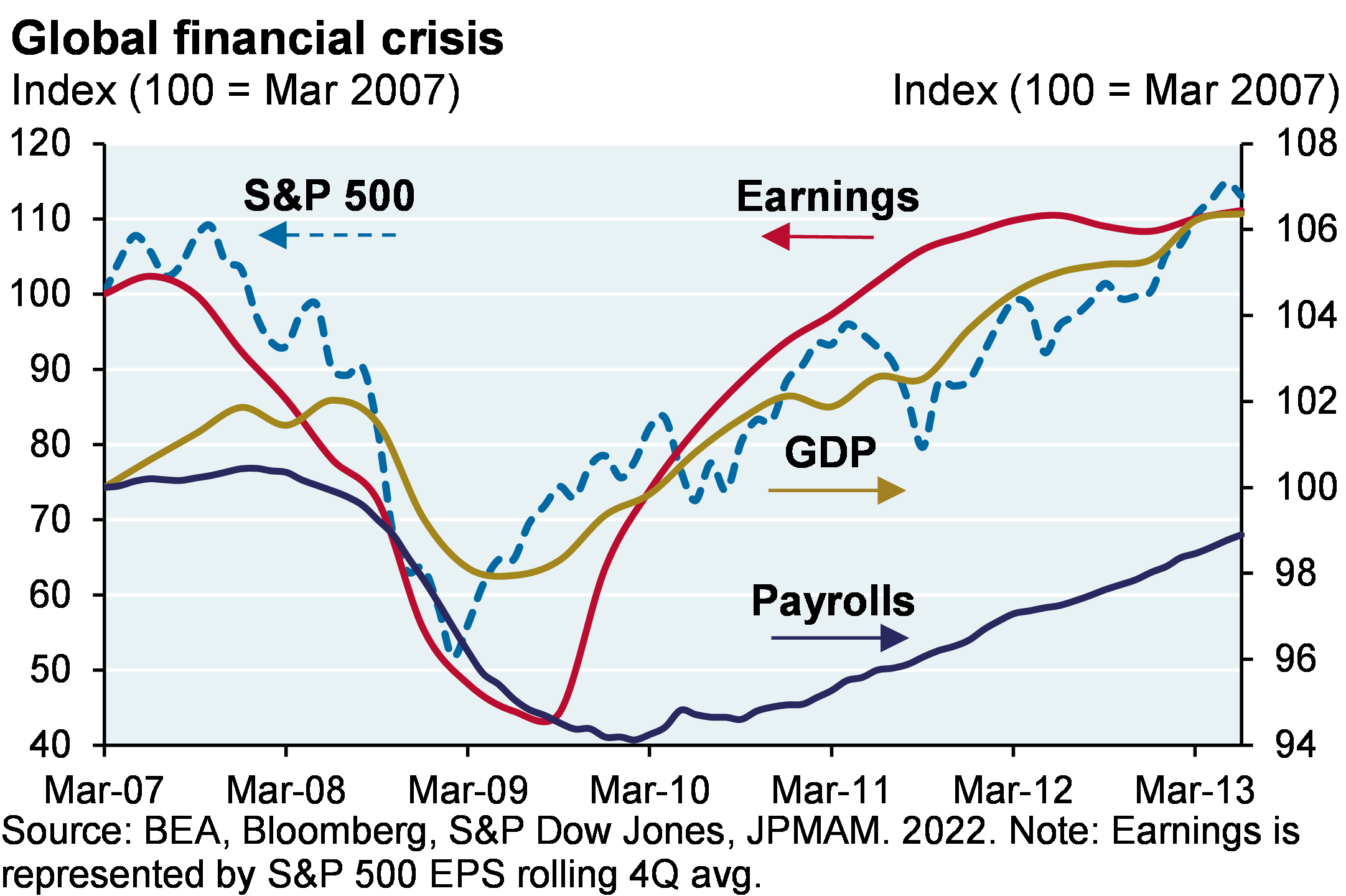

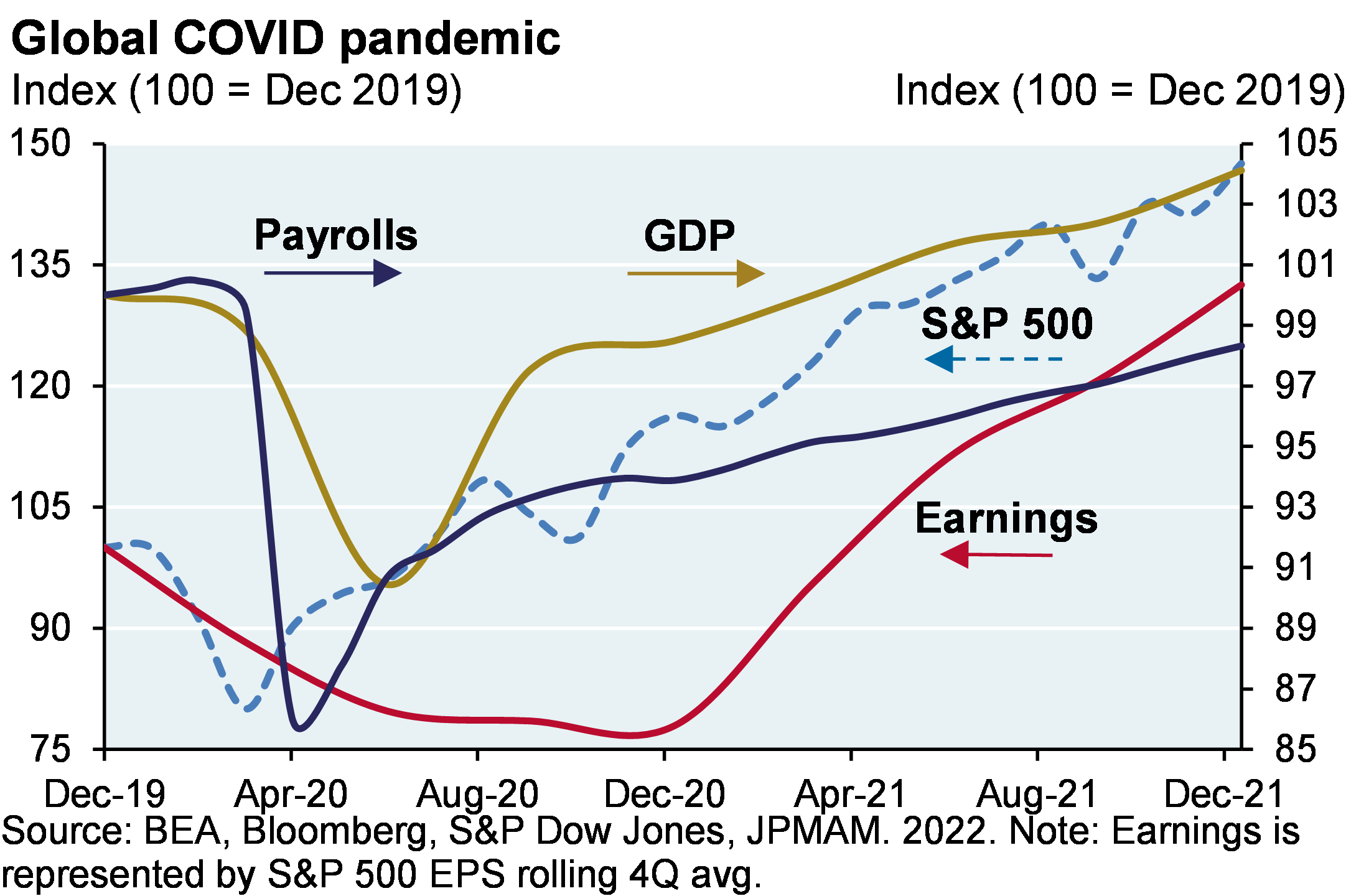

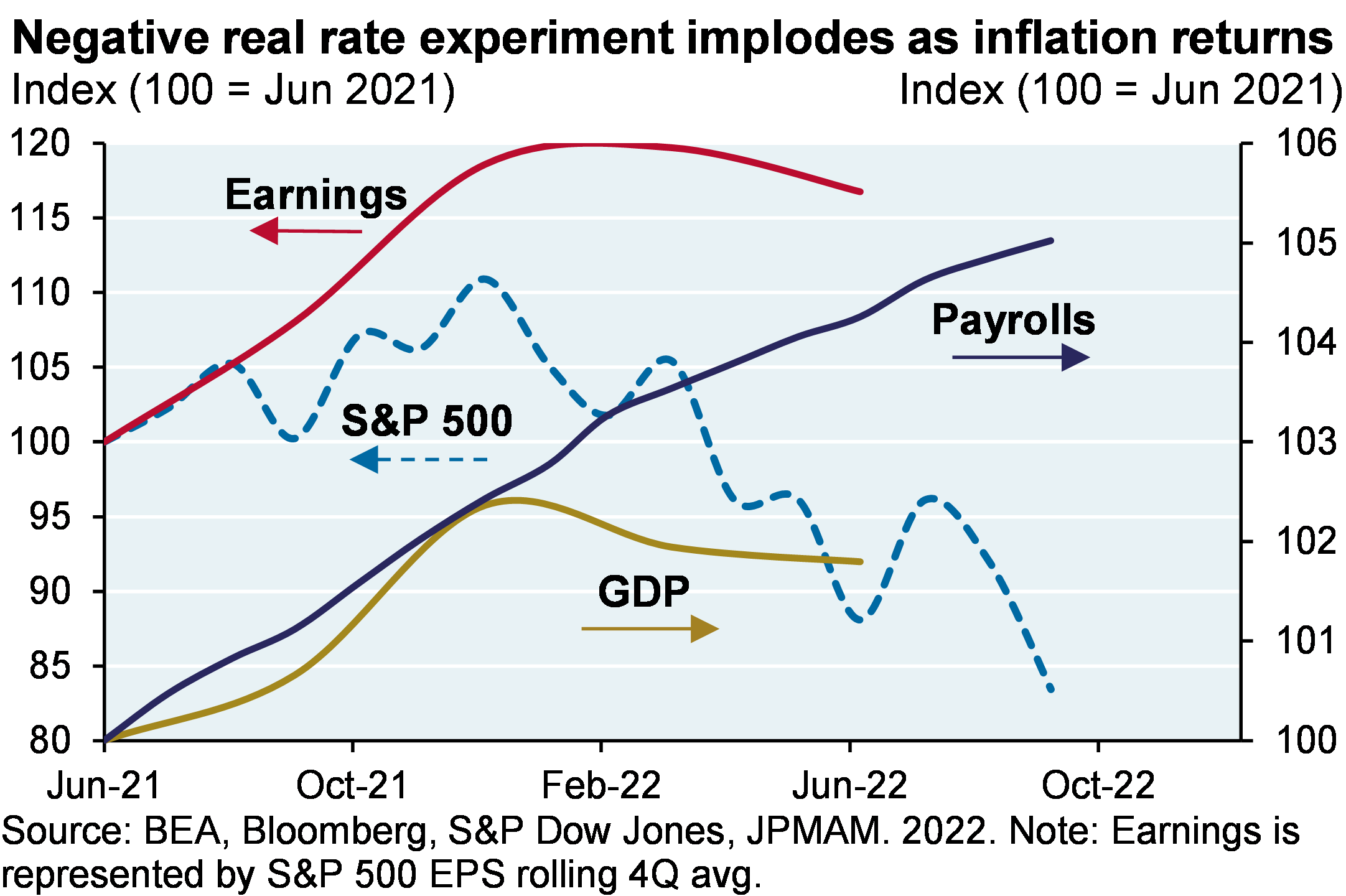

Let’s start with the Eisenhower recession, which is notable for the lack of monetary and fiscal stimulus deployed in what at the time was a pretty severe recession. Equities bottomed in December 1957, while earnings did not bottom until a year later. GDP and payrolls also didn’t start to improve until the middle of 1958. You will see the same pattern during the 1970’s stagflation, the 1980’s double dip recession, the S&L crisis of the 1990’s, the Global Financial Crisis and the COVID pandemic.

The Dotcom collapse is the outlier: the earnings decline preceded the equity market decline, there was barely a recession at all, and the mini-recession of 0.3% preceded the equity market bottom by more than a year.

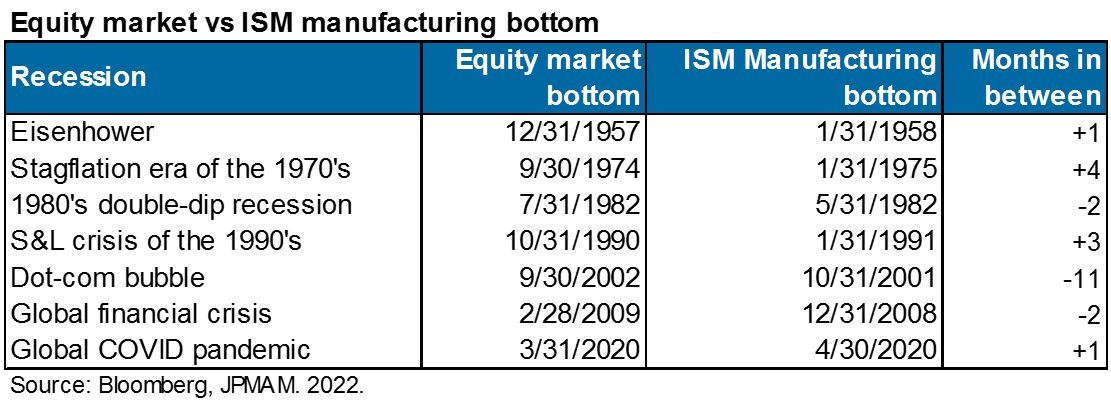

As for the latest bear market, it appears on the right. I see no reason why this cycle will not end up looking like most of the other ones. If so, the bottom in equities will occur even as news on profits, GDP and payrolls continues to get worse. When will that be? We will be watching the ISM manufacturing survey very closely. It has a good track record of roughly coinciding with equity market bottoms, as shown in the table. I would consider 3200-3300 on the S&P 500 index good value for long term investors, if such levels were reached sometime this fall/winter.

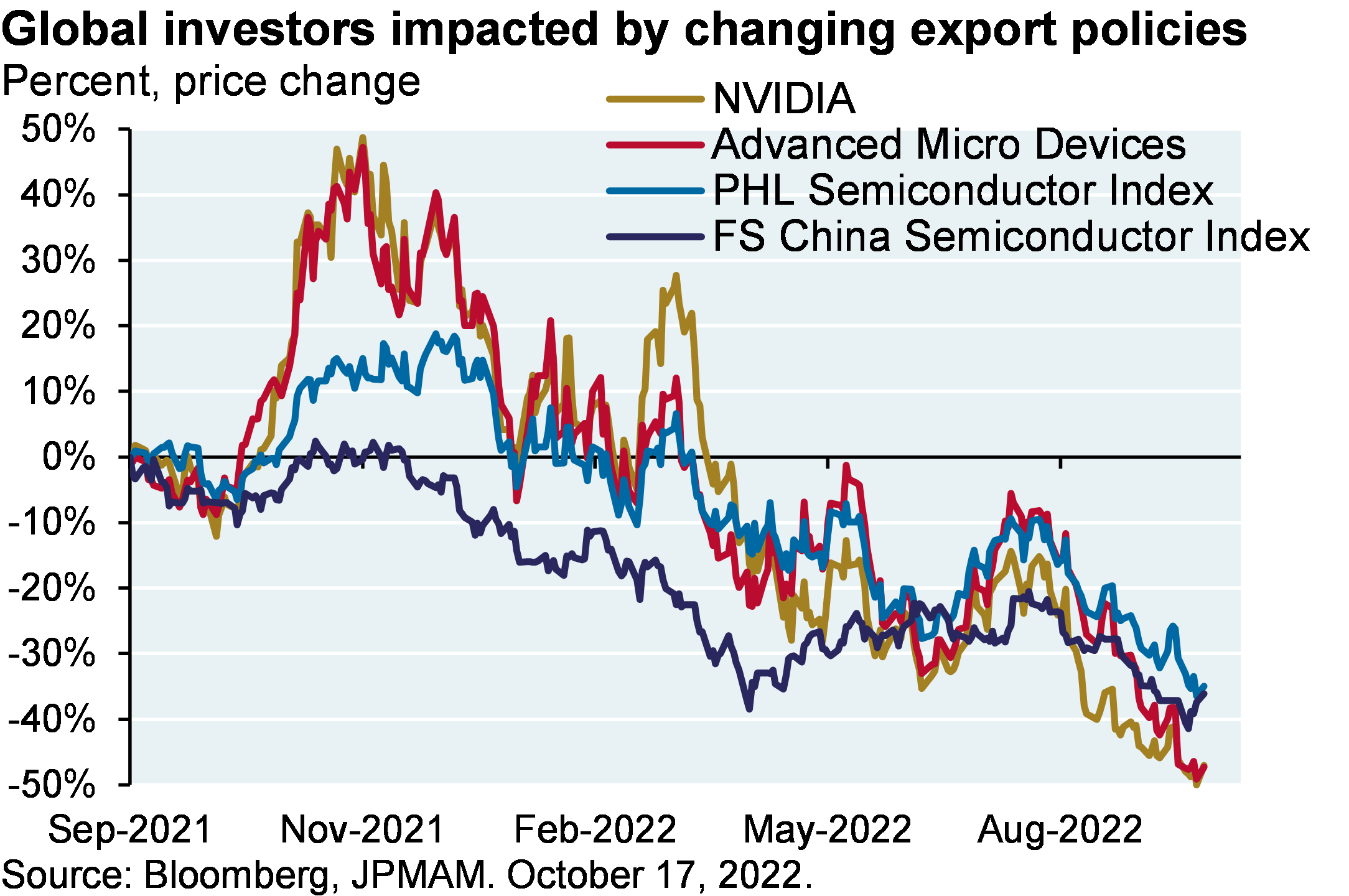

Thucydides Trap update: US semiconductor policy on China deepens the rift

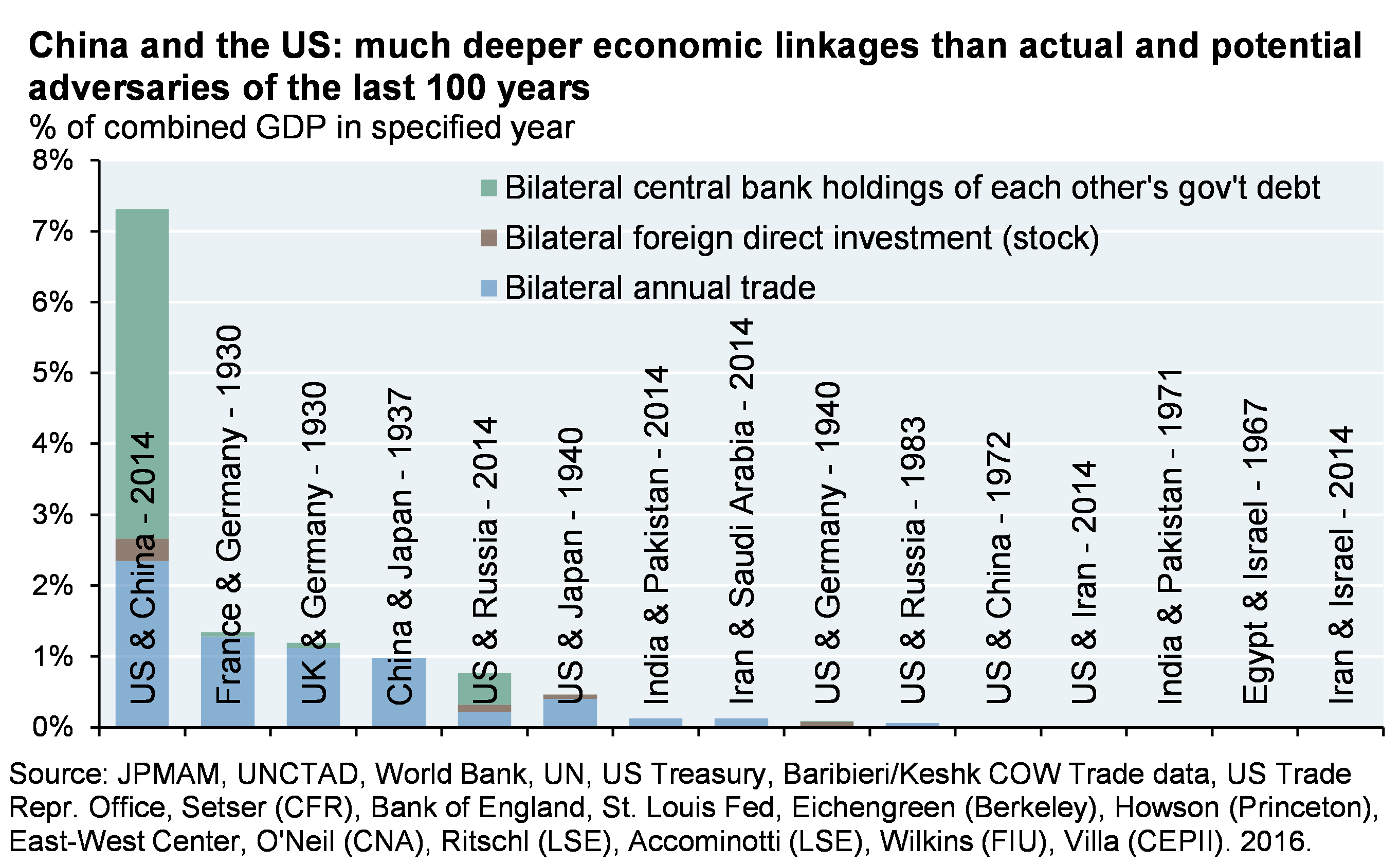

In May 2018, I published the chart below on economic ties between the US and China as a counterpoint to Graham Allison’s “Thucydides Trap” book. Allison’s work analyzed rising empires competing for power with incumbents. By Allison’s account, in 12 of 16 historical examples, competing empires ended up in military conflict, and Allison sees the US-China relationship as a rerun of these precedents. My chart was meant to highlight the unique economic ties between the US and China when compared to historical adversaries. As things stand now, certain fragments of the US-China relationship support my thesis: US imports from China in 2021 reached $540 billion (close to the pre-trade war peak in 2018), and China still holds ~$1 trillion of US Treasuries and Agencies. However, the latest developments on US semiconductor policy do not support it, and represent the most comprehensive change in US-China trade policy in decades.

The Trump administration took steps against ZTE and Huawei but left open the possibility of future engagement, perhaps in exchange for Chinese cooperation in other geopolitical areas. The latest moves by the Biden administration appear to close those doors, and for a very long time. A summary of the latest US actions1:

The new semiconductor policies focus on four areas in which the US has a current strategic advantage over China: AI chip designs, electronic design automation software, semiconductor manufacturing equipment and related equipment components

There are four interlocking elements of the new policy: (1) impede China’s AI industry by restricting access to high-end AI chips; (2) block China from designing AI chips domestically by cutting off China’s access to US-made chip design software; (3) block China from manufacturing advanced chips by cutting off access to US-built semiconductor manufacturing equipment; and (4) block China from domestically producing semiconductor manufacturing equipment by cutting off access to US-built components

China’s fusion of military and civil activities make it difficult to target the former without affecting the latter (prior bans on the sale of high-end Intel Xeon chips to China’s military didn’t work, since shell companies reportedly acted as an intermediary; Chinas military is reportedly still actively using US chip technology2)

The new policy: high-end AI chips can no longer be sold to any entity operating in China, whether that is the Chinese military, a Chinese tech company or a US company operating a data center in China. The new rules set a performance standard of what kind of chips can be sold; anything above that level requires an export license from the Dep’t of Commerce which may be subject to “presumption of denial”

The US is invoking something called the “foreign direct product rule”. The best way to explain it is to give an example of how it works. Any chip manufacturing operation anywhere in the world that seeks to build high end Chinese chip designs will risk losing its access to US semiconductor manufacturing equipment. As a result, Chinese chip design companies will not be able to outsource manufacturing abroad for advanced AI and supercomputing chips, and for the 28 Chinese organizations on the BIS Entity List, they will be blocked from outsourcing the manufacturing of any types of chips at all. [Note: Almost every advanced semiconductor fabrication facility in the world is critically dependent on US technology companies for initial purchase and ongoing onsite advice, troubleshooting and repair]

New licensing requirements for logic chip equipment sales for chips at 16 nanometers (nm) or less ends up blocking the sale of equipment to China that is several years old and already in use. For DRAM (short term memory) the limit will be 18 nm, and for NAND (long term memory) the limits are 128 layers and higher. Translating the semiconductor jargon: the new policies threaten the viability of some of China’s largest memory chip companies (some of whom have been hoarding as much US made equipment as they can)

These policies also require all “US persons” (citizens, residents and green card holders) to obtain a license to continue working on development, production or use of integrated circuits at certain Chinese semiconductor facilities

The scale and scope of these restrictions appear to be unprecedented. While they only apply to a subset of high performance AI-related chips now (such as those sold by NVIDIA which accounts for 95% of AI chip sales in China), the new chip performance benchmarks are being held constant. In other words, over time, more of the semiconductor market will be subject to these restrictions. These new policies complement the recently passed CHIPS Act and its $52 billion for US semiconductor research, manufacturing and workforce development.

What might happen now? US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan gave a speech last month that suggests that this may not be a one-time thing3:

“Earlier this year, the United States and our allies and partners levied on Russia the most stringent technology restrictions ever imposed on a major economy. These measures have inflicted tremendous costs, forcing Russia to use chips from dishwashers in its military equipment. This has demonstrated that technology export controls can be more than just a preventative tool. If implemented in a way that is robust, durable, and comprehensive, they can be a new strategic asset in the US and allied toolkit to impose costs on adversaries, and even over time degrade their battlefield capabilities”.

Next up: possible restrictions on US entities investing in Chinese technology companies as the focus shifts from the transfer of technology to the transfer of capital4.

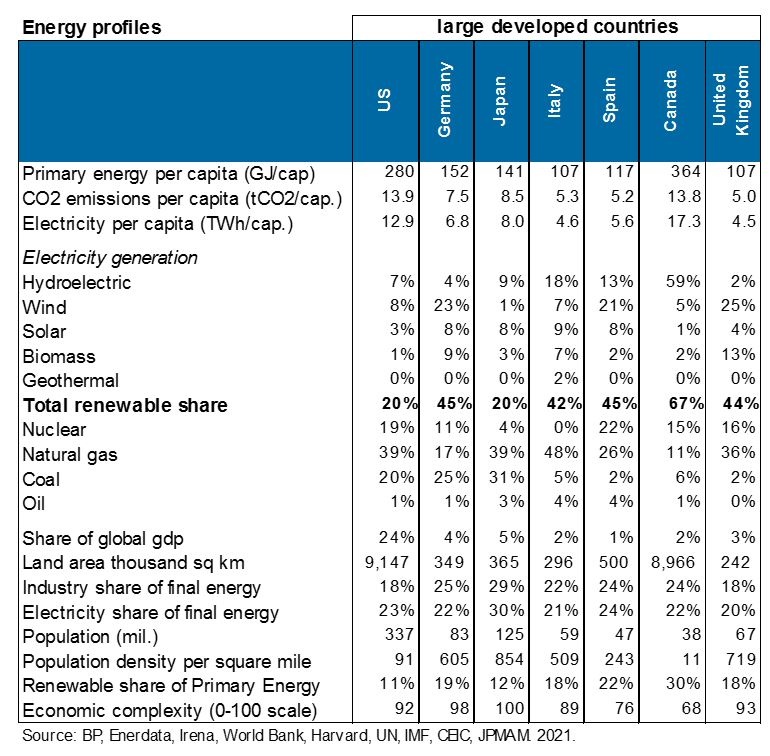

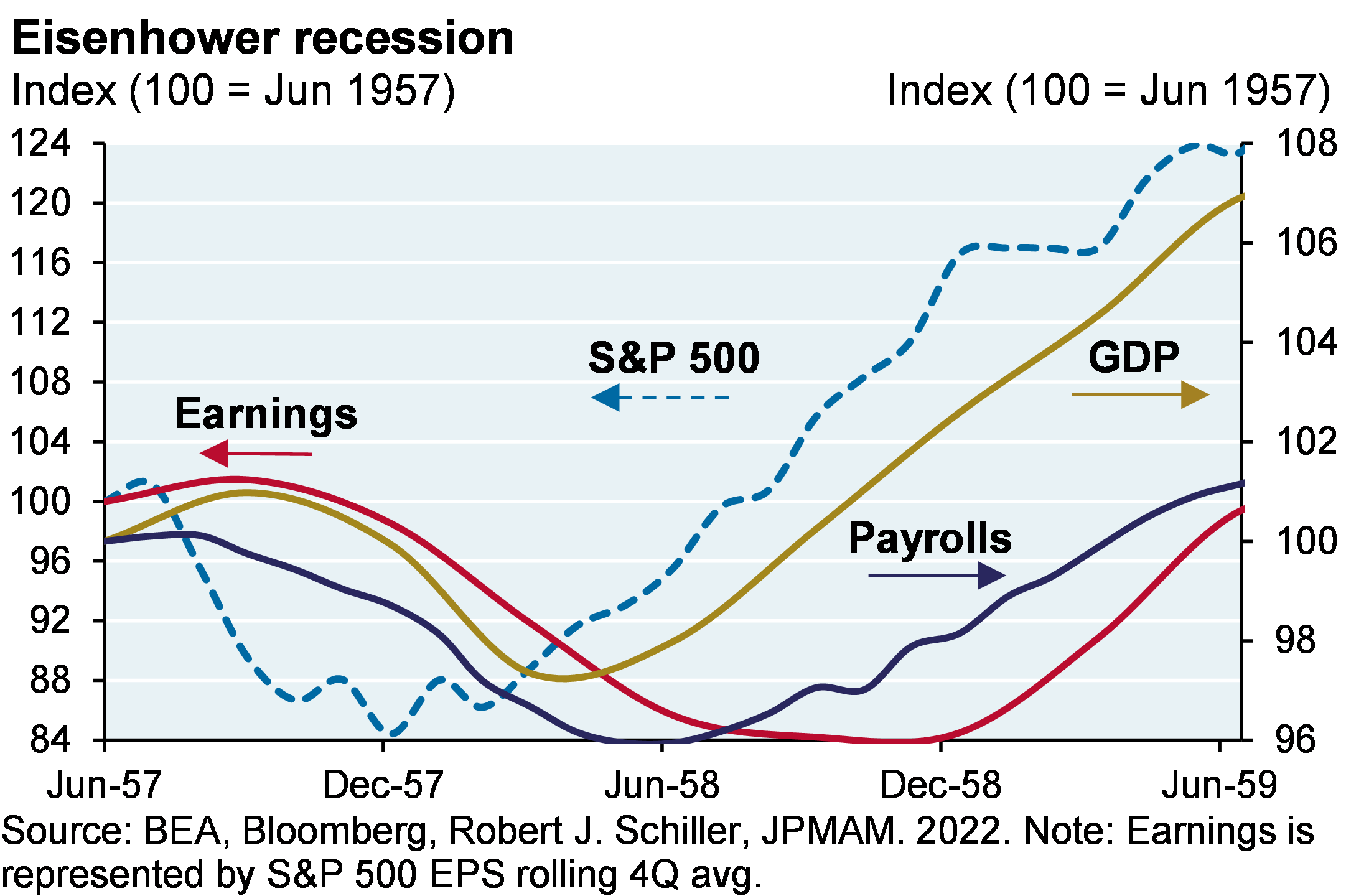

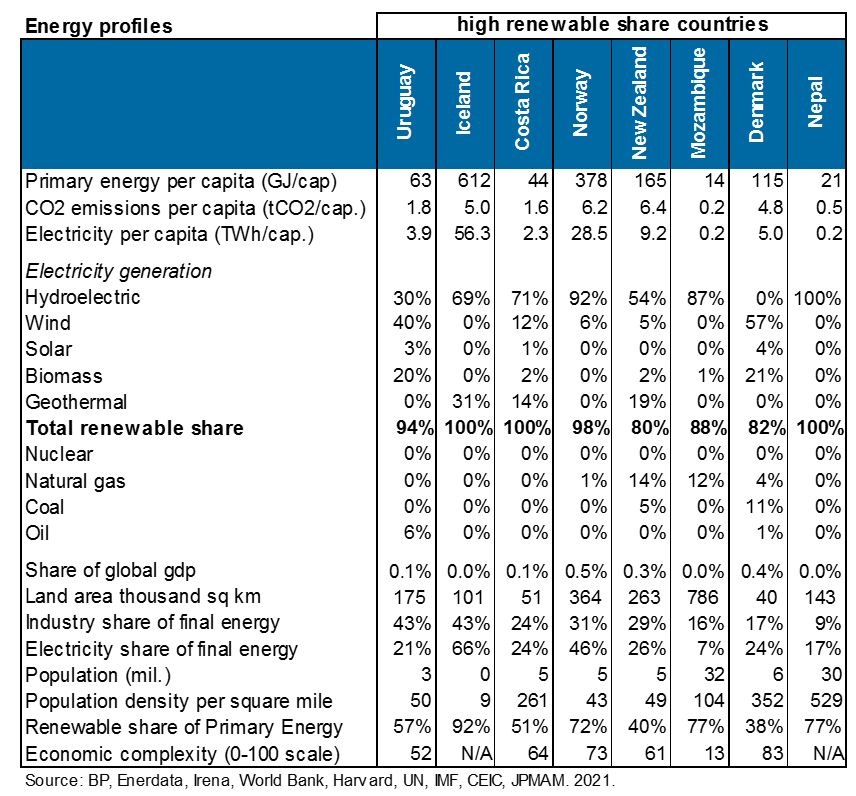

The Pitcairn Problem: the limited relevance of most small countries with high shares of renewable energy

More reruns: yet another article on tiny countries with high shares of renewable power generation as paragons of the future that are “leading the way” on sustainability without any mention of the factors that limit their relevance for larger developed and developing economies. The latest piece is on Uruguay, from the New York Times5. What’s missing is the broader context of how to understand Uruguay, Iceland, Norway, Costa Rica and other “Pitcairn” examples6.

Such countries generally have small shares of global GDP, small populations and lower population density. Low density countries face fewer challenges in terms of siting low density wind and solar power

They tend to be much smaller in terms of land area, an important consideration when thinking about the cost of transmission investment to load centers required for onshore and offshore wind, and solar power

They often have lower economic complexity (a measure of a country’s ability to produce a wide range of complex products across industries), which requires less developed energy systems

Most have abundant hydroelectric resources which contribute the lion’s share of electricity generation. Developed countries have already built out most of their suitable hydroelectric resources

Some have unique geothermal resources (Iceland, Costa Rica, New Zealand), or sugarcane-based biomass whose energy return on investment (“EROI”) is 7x higher than corn-based ethanol (Guatemala and Uruguay)

Uruguay is interesting in its use of biomass for backup power when wind conditions are low, and in this regard it shares a lot in common with Denmark, another small country with excellent coastal wind resources (40% capacity factors, similar to Uruguay) that uses biomass (manure, wood waste, energy crops and industrial feedstock) as a replacement for thermal power. Both small countries also benefit from proximity to much larger ones for grid stabilization services (Uruguay and Brazil, Denmark and Germany)

The combination of these attributes generally makes the Pitcairn group of countries much less relevant for larger, industrialized, urbanized countries. Most of the latter are pursuing a renewable future based more on wind and solar power, which requires raw materials, project siting, transmission investment and plenty of backup thermal power. More on all of this in next year’s energy paper.

Appendix charts: market indicators are generally downbeat

2 “Managing the Chinese Military’s Access to AI Chips”, June 2022, Center for Security and Emerging Technology

3 “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at the Special Competitive Studies Project Global Emerging Technologies Summit”, September 16, 2022

4 “White House Weighs Order to Screen US Investment in Tech in China”, WSJ, September 8, 2022

5 “What Does Sustainable Living Look Like? Maybe Like Uruguay”, NYT, October 7, 2022

6 Pitcairn Island, current population 47, where HMS Bounty mutineers settled in 1790

IMPORTANT INFORMATION

This report uses rigorous security protocols for selected data sourced from Chase credit and debit card transactions to ensure all information is kept confidential and secure. All selected data is highly aggregated and all unique identifiable information, including names, account numbers, addresses, dates of birth, and Social Security Numbers, is removed from the data before the report’s author receives it. The data in this report is not representative of Chase’s overall credit and debit cardholder population.

The views, opinions and estimates expressed herein constitute Michael Cembalest’s judgment based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Information herein may differ from those expressed by other areas of J.P. Morgan. This information in no way constitutes J.P. Morgan Research and should not be treated as such.

The views contained herein are not to be taken as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment in any jurisdiction, nor is it a commitment from J.P. Morgan or any of its subsidiaries to participate in any of the transactions mentioned herein. Any forecasts, figures, opinions or investment techniques and strategies set out are for information purposes only, based on certain assumptions and current market conditions and are subject to change without prior notice. All information presented herein is considered to be accurate at the time of production. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products. In addition, users should make an independent assessment of the legal, regulatory, tax, credit and accounting implications and determine, together with their own professional advisers, if any investment mentioned herein is believed to be suitable to their personal goals. Investors should ensure that they obtain all available relevant information before making any investment. It should be noted that investment involves risks, the value of investments and the income from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions and taxation agreements and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Both past performance and yields are not reliable indicators of current and future results.

Non-affiliated entities mentioned are for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an endorsement or sponsorship of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates.

For J.P. Morgan Asset Management Clients:

J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the brand for the asset management business of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its affiliates worldwide.

To the extent permitted by applicable law, we may record telephone calls and monitor electronic communications to comply with our legal and regulatory obligations and internal policies. Personal data will be collected, stored and processed by J.P. Morgan Asset Management in accordance with our privacy policies at https://am.jpmorgan.com/global/privacy.

ACCESSIBILITY

For U.S. only: If you are a person with a disability and need additional support in viewing the material, please call us at 1-800-343-1113 for assistance.

This communication is issued by the following entities:

In the United States, by J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc. or J.P. Morgan Alternative Asset Management, Inc., both regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission; in Latin America, for intended recipients’ use only, by local J.P. Morgan entities, as the case may be.; in Canada, for institutional clients’ use only, by JPMorgan Asset Management (Canada) Inc., which is a registered Portfolio Manager and Exempt Market Dealer in all Canadian provinces and territories except the Yukon and is also registered as an Investment Fund Manager in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. In the United Kingdom, by JPMorgan Asset Management (UK) Limited, which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority; in other European jurisdictions, by JPMorgan Asset Management (Europe) S.à r.l. In Asia Pacific (“APAC”), by the following issuing entities and in the respective jurisdictions in which they are primarily regulated: JPMorgan Asset Management (Asia Pacific) Limited, or JPMorgan Funds (Asia) Limited, or JPMorgan Asset Management Real Assets (Asia) Limited, each of which is regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong; JPMorgan Asset Management (Singapore) Limited (Co. Reg. No. 197601586K), which this advertisement or publication has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore; JPMorgan Asset Management (Taiwan) Limited; JPMorgan Asset Management (Japan) Limited, which is a member of the Investment Trusts Association, Japan, the Japan Investment Advisers Association, Type II Financial Instruments Firms Association and the Japan Securities Dealers Association and is regulated by the Financial Services Agency (registration number “Kanto Local Finance Bureau (Financial Instruments Firm) No. 330”); in Australia, to wholesale clients only as defined in section 761A and 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Commonwealth), by JPMorgan Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 55143832080) (AFSL 376919). For all other markets in APAC, to intended recipients only.

For J.P. Morgan Private Bank Clients:

ACCESSIBILITY

J.P. Morgan is committed to making our products and services accessible to meet the financial services needs of all our clients. Please direct any accessibility issues to the Private Bank Client Service Center at 1-866-265-1727.

LEGAL ENTITY, BRAND & REGULATORY INFORMATION

In the United States, bank deposit accounts and related services, such as checking, savings and bank lending, are offered by JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. Member FDIC.

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. and its affiliates (collectively “JPMCB”) offer investment products, which may include bank-managed investment accounts and custody, as part of its trust and fiduciary services. Other investment products and services, such as brokerage and advisory accounts, are offered through J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (“JPMS”), a member of FINRA and SIPC. Annuities are made available through Chase Insurance Agency, Inc. (CIA), a licensed insurance agency, doing business as Chase Insurance Agency Services, Inc. in Florida. JPMCB, JPMS and CIA are affiliated companies under the common control of JPM. Products not available in all states.

In Germany, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE, with its registered office at Taunustor 1 (TaunusTurm), 60310 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB). In Luxembourg, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE – Luxembourg Branch, with registered office at European Bank and Business Centre, 6 route de Treves, L-2633, Senningerberg, Luxembourg, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Luxembourg Branch is also supervised by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF); registered under R.C.S Luxembourg B255938. In the United Kingdom, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE – London Branch, registered office at 25 Bank Street, Canary Wharf, London E14 5JP, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – London Branch is also supervised by the Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority. In Spain, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE, Sucursal en España, with registered office at Paseo de la Castellana, 31, 28046 Madrid, Spain, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE, Sucursal en España is also supervised by the Spanish Securities Market Commission (CNMV); registered with Bank of Spain as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 1567. In Italy, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Milan Branch, with its registered office at Via Cordusio, n.3, Milan 20123, Italy, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Milan Branch is also supervised by Bank of Italy and the Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB); registered with Bank of Italy as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 8076; Milan Chamber of Commerce Registered Number: REA MI 2536325. In the Netherlands, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Amsterdam Branch, with registered office at World Trade Centre, Tower B, Strawinskylaan 1135, 1077 XX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Amsterdam Branch is also supervised by De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) and the Autoriteit Financiële Markten (AFM) in the Netherlands. Registered with the Kamer van Koophandel as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under registration number 72610220. In Denmark, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Copenhagen Branch, filial af J.P. Morgan SE, Tyskland, with registered office at Kalvebod Brygge 39-41, 1560 København V, Denmark, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Copenhagen Branch, filial af J.P. Morgan SE, Tyskland is also supervised by Finanstilsynet (Danish FSA) and is registered with Finanstilsynet as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 29010. In Sweden, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Stockholm Bankfilial, with registered office at Hamngatan 15, Stockholm, 11147, Sweden, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Stockholm Bankfilial is also supervised by Finansinspektionen (Swedish FSA); registered with Finansinspektionen as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE. In France, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Paris branch, which is regulated by the French banking authorities Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution and Autorité des Marchés Financiers. In Switzerland, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan (Suisse) SA, with registered address at rue de la Confédération, 8, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland, which is authorised and supervised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), as a bank and a securities dealer in Switzerland. Please consult the following link to obtain information regarding J.P. Morgan’s EMEA data protection policy: https://www.jpmorgan.com/privacy.

In Hong Kong, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Hong Kong branch. JPMCB, Hong Kong branch is regulated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, we will cease to use your personal data for our marketing purposes without charge if you so request. In Singapore, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Singapore branch. JPMCB, Singapore branch is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Dealing and advisory services and discretionary investment management services are provided to you by JPMCB, Hong Kong/Singapore branch (as notified to you). Banking and custody services are provided to you by JPMCB Singapore Branch. The contents of this document have not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in Hong Kong, Singapore or any other jurisdictions. You are advised to exercise caution in relation to this document. If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this document, you should obtain independent professional advice. For materials which constitute product advertisement under the Securities and Futures Act and the Financial Advisers Act, this advertisement has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. is a national banking association chartered under the laws of the United States, and as a body corporate, its shareholder’s liability is limited.

With respect to countries in Latin America, the distribution of this material may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. We may offer and/or sell to you securities or other financial instruments which may not be registered under, and are not the subject of a public offering under, the securities or other financial regulatory laws of your home country. Such securities or instruments are offered and/or sold to you on a private basis only. Any communication by us to you regarding such securities or instruments, including without limitation the delivery of a prospectus, term sheet or other offering document, is not intended by us as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or instruments in any jurisdiction in which such an offer or a solicitation is unlawful. Furthermore, such securities or instruments may be subject to certain regulatory and/or contractual restrictions on subsequent transfer by you, and you are solely responsible for ascertaining and complying with such restrictions. To the extent this content makes reference to a fund, the Fund may not be publicly offered in any Latin American country, without previous registration of such fund’s securities in compliance with the laws of the corresponding jurisdiction. Public offering of any security, including the shares of the Fund, without previous registration at Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission— CVM is completely prohibited. Some products or services contained in the materials might not be currently provided by the Brazilian and Mexican platforms.

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (JPMCBNA) (ABN 43 074 112 011/AFS Licence No: 238367) is regulated by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. Material provided by JPMCBNA in Australia is to “wholesale clients” only. For the purposes of this paragraph the term “wholesale client” has the meaning given in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Please inform us if you are not a Wholesale Client now or if you cease to be a Wholesale Client at any time in the future.

JPMS is a registered foreign company (overseas) (ARBN 109293610) incorporated in Delaware, U.S.A. Under Australian financial services licensing requirements, carrying on a financial services business in Australia requires a financial service provider, such as J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS), to hold an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL), unless an exemption applies. JPMS is exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act) in respect of financial services it provides to you, and is regulated by the SEC, FINRA and CFTC under U.S. laws, which differ from Australian laws. Material provided by JPMS in Australia is to “wholesale clients” only. The information provided in this material is not intended to be, and must not be, distributed or passed on, directly or indirectly, to any other class of persons in Australia. For the purposes of this paragraph the term “wholesale client” has the meaning given in section 761G of the Act. Please inform us immediately if you are not a Wholesale Client now or if you cease to be a Wholesale Client at any time in the future.

This material has not been prepared specifically for Australian investors. It:

May contain references to dollar amounts which are not Australian dollars;

May contain financial information which is not prepared in accordance with Australian law or practices;

May not address risks associated with investment in foreign currency denominated investments; and

Does not address Australian tax issues.

Reruns

Three reruns for investors: equity declines, Thucydides Trap update, and the Pitcairn Problem.

[START RECORDING]

FEMALE VOICE: This podcast has been prepared exclusively for institutional, wholesale professional clients and qualified investors only as defined by local laws and regulations. Please read other important information, which can be found on the link at the end of the podcast episode.

MR. MICHAEL CEMBALEST: Morning everybody and welcome to the October Eye on the Market. This one’s called Reruns, because there are three topics that I’m covering here that for investors are things that we’ve seen before or thought about before, talked about before. First one is on US equity markets, the second one is on the clash between US and China, and the third one is on renewable energy.

So let’s talk about equity markets first. When bear markets happen and the investment mistakes of the prior cycle get revealed, all of a sudden you tend to see bearish investment commentary intensify. And it’s almost like there’s a confessional aspect to some of this research, as if the people that write it are trying to atone for having missed some of the signals and risks during the prior cycle.

And I read a lot of research, maybe 1,500, 2,000 pages of research a week. And there’s a very consistent message right now that’s very bearish on earnings, valuations, inflation, central bank policy, housing, trade, energy, the surge of the dollar. I’m not saying that these things don’t matter, of course they do, we’ve been talking about them for a while. But at some point, the more markets go down, you have to start to shift your focus from the risks to the cycle to the shift in the cycle. And look, we spent a lot of time talking about young unprofitable companies, Fed mistakes, garbage SPACs, crypto, metaverse, et cetera, 18 months ago. But by the time a lot of assets reprice, it’s time to start shifting our focus towards where things go from here.

And that’s why I wanted to show a whole bunch of these charts. There’s a remarkable consistency. Equities tend to bottom several months, at least, before a lot of other things do during recessions. And I certainly do think the chances of a recession are quite high over the next few quarters, given what going on with Fed policy.

But let’s take a look at some of these things and start with the Eisenhower recession in the 70s, which was a pretty severe one, and also had not a lot of monetary and physical air drops associated with it. Equities bottomed in December in 1957, and GDP bottomed six, seven months later and then payrolls and then earnings bottomed. And by the time a lot of those GDP and payrolls and earnings and things like that were getting better, the equity markets were already up pretty substantially.

And so there’s a bunch of charts in here for the, as I mentioned, the Eisenhower recession, the stagflation era of the 1970s, the double-dip recession in the 80s, the S&L crisis in the 90s, the global financial crisis 12 years ago, and then the COVID pandemic. In each one of these, the patterns were the same. The equity markets go down first, and then a whole bunch of things go down later.

And so I just want to make sure as investors, that we and you are focused on the equity markets and how they tend to discount in terms of time and magnitude, the declines and other things. So we’ll be following payrolls and we’ll be following the decline in earnings, which is certainly coming, and we’ll be following the decline in GDP. But it’s very important to understand that in almost every cycle, the decline in equity markets predates that by quite a bit.

And if we had to pick a single variable that does coincide with the bottom in equity markets, it happens to be the ISM manufacturing survey. We’ve talked about this before. If there were any one variable that you had to hang your hat on, the ISM has the closest coincident timing with the bottom in equity markets. And in most cycles, they bought them together within one or two months of each other. The only exception here was the dot-com bubble, recession collapse, where everything was all mixed up. The equity bottom actually happened after the recession and after the decline in earnings. So that’s the one outlier here.

But I have no reason to believe that this cycle is going to be very different from the other six of them. So we’ll be watching the ISM survey closely, has a really good track record of coinciding with equity market bottoms, and I would consider something like 3,200 to 3,300 on the S&P index if we got there sometime this fall or winter, pretty good value for long-term investors.

The second rerun topic is the US and China. And what I mean by rerun is there was a book by Graham Allison. I forgot what year it was written, but it was called The Thucydides Trap. And it had to do with how rising empires compete for power with incumbent empires. And by his account, in 12 of 16 historical examples, competing empires end up in military conflicts with each other. And obviously he’s writing this book as a parallel to the current US/China relationship.

I published a chart at the time when the book came out showing the economic ties between the US and China through bilateral central bank holdings, foreign direct investment and trade that were much higher than all sorts of historical examples. And my chart was meant to highlight how these unique economic ties between the US and China were different and could end up with a different outcome.

And as things stand now, there are certain aspects of the US/China relationship that are still supporting that general thesis. In 2021, despite the Trump tariffs, the US imported $540 billion of goods from China, which was almost the same as the pre-trade war peak in 2018. And China still holds about a trillion dollars of US treasuries and agencies.

So certain aspects of the US/China relationship are still intact. Obviously others are not. There’s been a lot of things changing about the Committee for Foreign Investment in the United States and all sorts of policies affecting bilateral flows. And the latest salvo from the US is probably the way that a lot of people see it who watch this stuff closely, the most comprehensive change in US/China trade policy in decades, and it has to do with semiconductors.

So when you look at what the Trump Administration did and the steps they took against Huawei, they left open the possibility of future engagement maybe in exchange for Chinese cooperation on other geopolitical areas. But these latest moves by the Biden administration may close those doors for quite a long time.

So there are four interlocking elements of this new policy, and they all have to do with semiconductors, and specifically the high-end, high-performance semiconductors, where the US has a strategic advantage over China. So the elements of this new policy are to impede China’s artificial intelligence industry by restricting access to high-end chips to block China from designing those chips domestically by cutting off access to our chip design software, to block China from manufacturing the chips by cutting off access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and then to block China from producing the equipment by cutting off access to components. So it’s a pretty comprehensive policy.

And essentially what the policy states is that high-end chips can no longer be sold to any entity operating in China, whether it’s the Chinese military, a Chinese tech company, or a US company operating at a data center in China. And export licenses will be needed and according to the Department of Commerce, a lot of these requests are going to be subject to the presumption of denial.

And so we go through a little bit more of the details here. There’s an excellent piece from the Center for Strategic and International Studies that goes through a lot of the details, and we summarize that here. The bottom line is that some of the new policies are pretty restrictive. Any chip manufacturing operation anywhere in the world that seeks to build high-end chip designs will end up, may end up losing its access to US semiconductor, manufacturing, equipment, support, advice, repair, et cetera.

So this is a pretty big deal. Some of the policies only apply to super-high-end chips, but the performance standards are being held constant. So over time, more and more of the semiconductor markets going to be subject to these restrictions. And when you read the comments from National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, it makes it pretty clear that the US is looking at these kinds of things as a new strategic asset in the US toolkit, which he describes as imposing costs on adversaries and even over time, degrading their battlefield capabilities.

And what’s up next, there’s talk of restrictions on US entities investing capital in Chinese technology companies as the focus shifts from the transfer of technology to the transfer of capital. We wrote a paper in our institutional business. We have a strategic advisory investment committee and we write one or two papers a year, and the last one was on de-globalization. And this certainly is another element in the de-globalization, in the gradual de-globalization that’s taking place, all of which has the potential to raise the cost of goods and services in places that are trying to now rebuild and re-onshore all sorts of production and supply chain capability.

The last rerun topic is on renewable energy and what I’m calling the Pitcairn problem, which are press articles that you see all the time on tiny countries that have very high shares of renewable power generation, mentioning them as paragons of the future that are leading the way on sustainability, without mentioning any of the factors that limit their relevance for everybody else, and specifically for the larger developed and developing economies.

The latest example of this is a piece in The New York Times on Uruguay, which was a great read and very interesting. The problem is it was completely missing, as these articles usually do, the broader context of how to understand countries like Uruguay, Iceland, Norway, Costa Rica, and other similar tiny places in terms of how they’re getting these high shares of renewable power generation.

So first of all, most of these countries tend to have very small shares of global GDP, very small populations, and low population density. They also tend to have lower economic complexity, which measures a country’s ability to produce a wide range of goods and services. That means they need less developed energy systems.

They also tend to be pretty small in terms of land area, which is a very important consideration when you think about the transmission investment required to bring wind and solar power to where the load centers are. So it’s one thing to build wind on the shore of Denmark to power things in Denmark. It’s another thing to build wind in certain places in the United States and have to transmit that to where the load centers are; it’s very different.

But the biggest issues are the ones that don’t get discussed enough. If you find a country that has anywhere, 40, 50, 60, 70% renewable shares, chances are it gets the lion’s share of its electricity generation from hydroelectric power. And most developed, and even a lot of developing countries have already built out their suitable hydroelectric resources, and so it can be very misleading to be talking about these paragons of renewable generation that happen to be small little places with spectacular hydroelectric resources.

Some of the other ones have really unique geothermal resources, like Iceland, Costa Rica, and New Zealand, or they have a lot of sugar cane-based biomass. And the reason that it’s important to specify sugar cane is that sugar cane-based biomass has seven or eight times more energy per unit of investment than corn ethanol does, and Guatemala and Uruguay are examples of that.

So the combination of all these attributes makes this little Pitcairn group of countries much less relevant for everybody else. They’re interesting to learn about. But the big developed and developing countries in the world are pursuing a renewable energy future based not on hydroelectric and not on geothermal and not on sugar cane-based biomass, but on a lot more wind and solar power and maybe some of that being used to produce hydrogen, all of which requires a lot of raw materials, a lot of critical minerals, a lot of project- siting, a lot of transmission investment, and plenty of backup thermal power for when those other things are working.

So more of that on, more of all of this in next year’s energy paper. But I did want you to, everyone to understand the limitations of some of these smaller countries and their relevance for everybody else. And there are some tables in here with lots of statistics that you might find interesting.

So that’s enough for now. We will probably talk to you again after the midterms, which I don’t really expect to be much of a market-moving event compared to everything else that’s going on with the Fed and the pending recession, declining earnings, and everything else. So thanks for listening, see you next time.

FEMALE VOICE: Michael Cembalest’s Eye on the Market offers a unique perspective on the economy, current events, markets, and investment portfolios, and is a production of J.P. Morgan Asset and Wealth Management. Michael Cembalest is the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset Management and is one of our most renowned and provocative speakers. For more information, please subscribe to the eye on the market by contacting your J.P. Morgan representative. If you’d like to hear more, please explore episodes on iTunes or on our website.

This podcast is intended for informational purposes only and is a communication on behalf of J.P. Morgan Institutional Investments Incorporated. Views may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as personal investment advice or a solicitation or recommendation. Outlooks and past performance are never guarantees of future results. This is not investment research. Please read other important information, which can be found at www.JPMorgan.com/disclaimer-EOTM.

[END RECORDING]