When the yield cupboard is bare

Investors are hungry for income, but interest rates are low and moving out the yield curve is unappealing. Short-term bonds aren’t even keeping pace with inflation, while longer-term bonds with marginally higher yields are particularly vulnerable to rising rates.

Traditional credit risk isn’t the answer, either. Spreads are exceptionally tight, perhaps reflecting strong macro fundamentals but offering little to entice investors seeking income. From investment grade corporate credit down through high yield bonds, prospective returns from credit are thin at best.

So, if the classic approach to yield enhancement—adding duration and credit risk—is off the table, what can an investor do?

Finding returns in capital structure

Investors have a variety of tools available to them when it comes to improving the income generation and stability of returns in their portfolios. We have explored this broad topic elsewhere, but here we focus on an underutilized mechanism for income enhancement: capital structure—specifically, the ability to trade seniority for increased returns. We refer to this strategy as subordinated or mezzanine debt investing, given its midlevel position in the capital structure between the riskier equity layer and the safer senior debt layer.

A range of methods are available to take advantage of capital structure, including subordinated debt, preferred equity, structured credit strategies and real estate mezzanine lending. In the current market, one of these pathways—real estate mezzanine—offers a particularly compelling combination of attractively priced assets, superior internal risk diversification and multiple avenues for the application of manager skill.

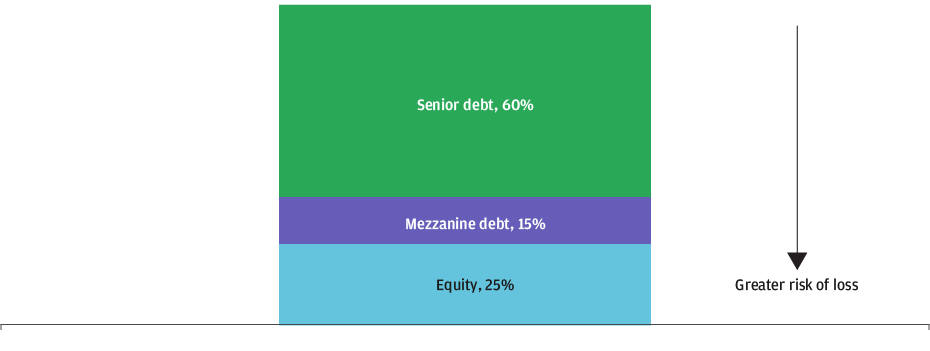

The risk-reward proposition for utilizing subordinated and mezzanine debt rather than more traditional senior debt is straightforward. By moving from a more senior to a more junior position in the capital stack, an investor edges closer to the first-loss position (equity) and increases the risk of capital impairment if the equity cushion disappears. In return for assuming this risk, the investor receives substantially higher coupons than the (now safer) senior debt holders do. The equity owner, in turn, needs less capital to acquire assets, increasing prospective returns without diluting ownership. Although the specific components of a capital structure can vary in relative size and complexity, the relationship among them is intuitive: The greater the equity cushion, the less risk to the mezzanine and senior debt holders; the more equity and mezzanine debt, the lower the risk to senior debt (Exhibit 1).

In moving from a senior to a more junior position in the capital stack, investors assume some additional risk of impairment in return for substantially higher coupons

Exhibit 1: A simplified example of capital structure

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

One of the key benefits of this type of investment is that it allows investors to increase returns without reducing the quality of the underlying assets or increasing their duration. Nevertheless, it is critical to carefully consider the nature of the underlying assets and the manner in which a subordinated position is established. Below, we describe three of the more common opportunities in this space and their relative pros and cons.

Subordinated corporate securities: Limited diversification is a concern

In the public fixed income markets, a borrower can issue subordinated debt but investors need to be wary: The risk profile can be quite volatile, given the potential sensitivity of the debt price to a drop in the value of the issuer’s equity. Corporate subordinated debt is generally less common and tends to be concentrated in the financial sector, making the construction of a prudently diversified portfolio challenging. Preferred equity and bank capital securities, which occupy a similarly subordinated position, do offer reasonably large pools of investible assets. Because they reside closer to the first-loss equity, however, they are more closely correlated to equity markets—and thus generally riskier than other forms of subordinated debt.

Structured credit strategies: Exposed to correlation risk

A mezzanine tranche drawn from a diversified pool of corporate senior debt securities, whether structured as a collateralized debt obligation (CDO) or a collateralized loan obligation (CLO), offers improved resilience by reducing the idiosyncratic risk of exposure to any single name or sector. Furthermore, the liquidity of these underlying assets—and the relatively high transparency they afford with respect to their financial condition—make active management of these portfolios a potential source of value. However, the relatively high correlations across corporate borrowers and their collective vulnerability to a broad credit market or equity market sell-off make CDOs and CLOs subject to high mark-to-market volatility, even if the probability of outright capital loss is modest. The historically low levels of credit spreads available in the current market also diminish the potential for subordination strategies to improve returns.

Real estate mezzanine: Driven by bottom-up underwriting expertise

Real estate markets, however, offer investors direct exposure to mezzanine loans that are underwritten at the asset level. Asset managers can then group these loans in a pooled portfolio diversified by geography, asset type, sponsor and maturity. Real estate mezzanine loans can exhibit other favorable characteristics:

- High quality core real estate assets draw returns from income rather than price appreciation, making the capital structure more stable and reducing price volatility.

- Individual core real estate assets can embed significant internal diversification from many tenants/lessees, which reduces idiosyncratic default risk at the asset level.

- Real estate mezzanine lenders can retain significant control rights over the underlying assets, adding flexibility in times of stress.

Of these three options, the most compelling opportunity lies in the core real estate mezzanine debt market, where attractive yields and the quality of the underlying assets create a stable platform for subordinated lending. The evolution of real estate capital structures in recent years is also key; we now see more stable and well-capitalized structures that are well suited to strategic institutional use of the mezzanine asset class.

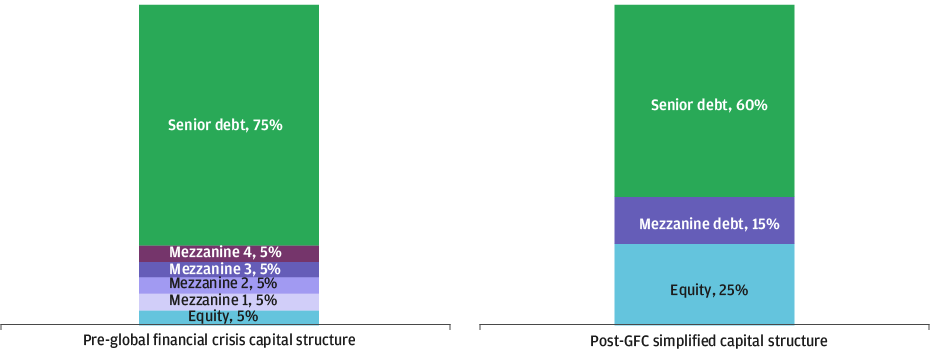

Lessons from past crises: Avoid unnecessarily complex capital structures

Historical critiques of mezzanine investments have focused on their perceived complexity and the inherent risks of multi-tranche capital structures resting on a thin foundation of equity capitalization. Certainly, this type of unbalanced structure was true of many deals originated prior to the global financial crisis (GFC), which featured very low levels of true equity, several thin layers of mezzanine debt and a larger pool of senior debt that required coupon income (Exhibit 2). In retrospect, the challenges these capital structures faced during the GFC seem obvious:

- Narrow equity capitalization meant that modest losses in asset value quickly impaired the mezzanine tranches, increasing mark-to-market volatility.

- The volume of senior debt drew income out of the capital structure, leaving less cash flow available for mezzanine investors and encouraging more aggressive tranche segmentation to generate returns.

- The large number of thin mezzanine tranches, combined with volatility in underlying asset prices, challenged investors to determine which levels of the capital structure retained value and which did not.

- The change of control from equity to mezzanine investors occurred rapidly during the crisis and was subject to legal uncertainty. Some investors with little or no experience in—or appetite for—direct ownership wound up in control of sizable assets.

Real estate capital structures have evolved dramatically since the GFC and are now more stable and better capitalized

Exhibit 2: Examples of pre-GFC and post-GFC simplified capital structure

Source: J.P. Morgan Asset Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Fortunately, investors have learned these lessons and markets have evolved to support simpler and better-capitalized structures. Since the GFC, senior real estate lenders have reduced leverage to 50%–60% loan-to-value (LTV) ratios, offering an opening for equity and mezzanine investors to capture a larger portion of the overall capital structure. This shift has been structurally positive for the real estate mezzanine debt asset class, which now enjoys a larger equity cushion for downside protection and a smaller amount of senior debt to siphon off income. Fewer tranches of debt allow investors to gain better visibility into the relationship between underlying asset values and the risk position of the mezzanine tranche itself.

The role of skill in mezzanine investing

Real estate mezzanine debt is exceptionally well suited to active management, given the breadth of skill required to identify attractive investments and the heterogeneity of the underlying assets. Strong relationships across the real estate and banking community are essential to sourcing attractive investment opportunities. A reputable and seasoned team facilitates working with the most demanding lenders and property owners (sponsors). The ability to underwrite the property itself is essential, even though the mezzanine investor usually has an unsecured position behind the senior lender’s mortgage. Understanding a sponsor’s operating strategy provides insight into the investment and may prove valuable because a mezzanine lender would be in a position to assume ownership of the property in the event of a default. As a component of a broad real estate investment platform, targeted mezzanine lending offers a unique and diversifying source of significant income-driven returns with less volatility than traditional equity.

A new appreciation for hybrid asset classes in portfolios

We began by describing the yield challenge that is pushing investors to seek new paths to reach their return objectives. In some instances, this search can take the form of risky yield chasing, but not always: Hybrid asset classes that share some equity-like and bond-like characteristics offer a compelling opportunity. For total return-focused investors seeking to reach their return targets, they present an attractive alternative to historically low expectations for fixed income. For liability-driven investors seeking to reduce portfolio volatility and increase income generation, they present an alternative to the volatility of traditional equity.

Real estate mezzanine debt epitomizes this trend. Positioned directly between equity and senior debt in the capital structure, mezzanine debt provides enhanced return potential relative to traditional debt and a lower risk profile than equity. Although not as liquid as public market strategies, mezzanine debt can be accessed via open-end fund structures with liquidity profiles that remain suitable for institutional investors with uncertain future capital needs. Finally, the underlying source of risk—core real estate—offers attractive diversification within portfolios dominated by highly correlated equity and credit exposures. As asset allocations continue to diversify in response to a low return world, the powerful benefits of using capital structure to extract attractive risk-adjusted returns are coming into focus.