I’ve been asked frequently in recent weeks whether I still feel like Q1 of this year will mark a turning point, where the effects of global central bank policy reversals are significant enough to affect markets. The short answer is that I still expect policy-driven volatility, and it still makes sense to expect it in the next few months. To me, the case is somewhat stronger now than it was eight weeks ago, and a continued risk melt-up actually helps the argument further. Making market prognostications is always a tricky business though, especially when it’s as nuanced as the case I am going to lay out briefly here today, but I hope this will help at least frame the debate.

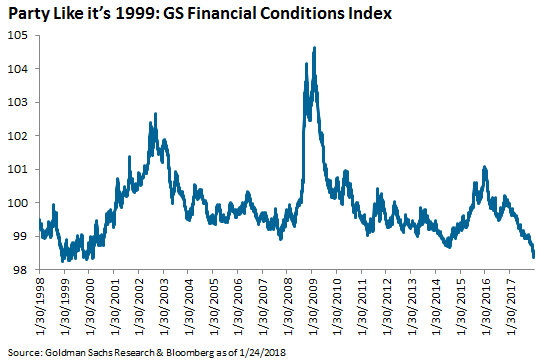

As I discussed in my last post in late November, the primary driver of markets then, and to only a slightly lesser extent now, is the persistence of global central bank balance sheet expansion. Obviously all of it (and more) is occurring outside the US by the ECB and BOJ, because of course the Fed is actively shrinking its balance sheet now. I label this current macroeconomic period as “Phase Zero,” the period of price action which precedes the effects of true aggregate policy tightening, the latter of which I think will have three distinct phases of its own. In Phase Zero, we see generalized asset buoyancy across everything – a continuation of the asset price inflationary effect of Quantitative Easing (QE), as QE remains the driving force. Risk assets perform well, and interest rates remain “contained,” which is to say suspiciously low given the background economic performance, even though they may drift higher. It’s pretty clear we’re in Phase Zero, looking at the price action and dearth of cheap assets. This environment where interest rates are contained, credit spreads are tight (and tightening), PE ratios are elevated (and rising), volatility is low (and falling), and the dollar is weak (and falling), is the textbook definition of loose (and loosening) financial conditions. Sure enough, financial conditions indices show the loosest level since 1999:

Now, if the asset price inflationary effects of global QE result, almost by definition, in a loosening of financial conditions, then any reversal in asset price inflation as central bank aggregate balance sheet flow shifts from positive to negative will tighten financial conditions. I reiterate my point from the first couple blogs on this topic: whether or not Quantitative Tightening reverses asset price inflation is a matter of intense debate. My view is that it will, and the net balance sheet flow is what matters (see: here and here). If and when the reversal in aggregate policy stance of global central banks starts to bite, we will enter Phase 1 of the adjustment, which is simply a period of asset price inflation unwinding: spreads wider, stock valuations lower, interest rates and volatility higher. Note this is a period of high correlation, where core rates may not serve as an effective hedge for risk assets, with instead all prices retracing. Phase 1 will be an uncomfortable time, and one in which financial conditions in aggregate will tighten materially because most or all of the sub-components will be tightening simultaneously.

I do believe Phase 1 will be mercifully short though. Financial conditions, broadly defined, reflect the cost for consumers and corporations to obtain financing: equity or debt, domestic or foreign. Those costs are primarily driven by market forces, and yet financial conditions remain the primary transmission mechanism for monetary policy to affect the broader economic fundamentals. So, policy and economic performance are inextricably linked by markets. Such a dramatic tightening, even from a very loose starting point, will begin to convince the market of the necessity of a central bank response. This is Phase 2. Risk assets continue to trade weak, as tightening financial conditions impact real economic performance, but the correlation flips back to “normal” on the interest rate component and yields fall, albeit from higher levels achieved in Phase 1. The interest rate rally will be justifiable in the market despite QT’s impact on bond supply, because the market will anticipate a dovish “relent” on policy, whether that means reduced QT, slower hikes, lower terminal rate, or a combination.

And Phase 3 is the relent itself: a policy response which slows the pathway to “normalizing” interest rates and balance sheets. In Phase 3, interest rates are range-bound, but risk assets recover and volatility declines. The policy response prevents a material economic slowdown, and the expansion is prolonged. I think all of this is possible within 2018, in the end with asset prices and interest rates returning roughly to where they are now, but going through a cycle of volatility as the macroeconomic drivers evolve through these Phases.

For a while, loosening financial conditions in the face of central banks normalizing policy could be considered a virtue, rather than a concern. Even though tightening monetary policy has but one purpose: to ward off inflation pressure, in the absence of inflation pressure (as was the case for 2017) higher policy rates without tight financial conditions give the Fed more flexibility without adverse effects on growth or job creation. However, for a number of reasons, sentiment seems to be shifting toward concern about inflation pressures building. At this point, the tightening cycle has progressed for two years without inflation pressure, and merely the passage of time brings presumed eventual inflation closer to the present. Unemployment is probably close to NAIRU, and job creation is sufficiently strong to continue reducing the unemployment rate. Couple this with the incremental fiscal stimulus in 2018 (and beyond) from the tax bill, and the weak dollar impact on rising import prices, and those loose financial conditions in the face of policy normalization no longer look so virtuous.

If the purpose of monetary policy tightening is to ward off inflation pressure, and financial conditions are the primary transmission mechanism, the stark absence of financial conditions tightening now may look like a problem. To a policymaker worried about inflation pressure on the horizon, policy tightening needs to be more aggressive, in order to get some pass-through to financial conditions. Outgoing NY Fed President (and godfather of the GS Financial Conditions Index) Bill Dudley commented on January 18 in the Financial Times: “…financial conditions are very accommodative – that is something I put a fair amount of weight on, [namely] the fact that we have been tightening monetary policy over the last couple of years, yet financial conditions are actually easier today than when we began to start to tighten monetary policy.”

The shifting sentiment on inflation and its resulting reversal in the lens through which policymakers may view loose financial conditions leaves the next few months still in play for the move to Phase 1 – when aggregate policy tightening starts to show up in markets.