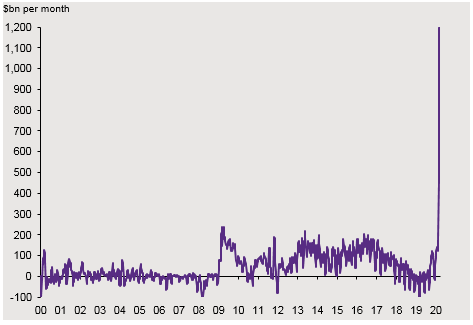

The COVID-19 crisis has seen the fastest deterioration in the economic outlook in living memory, and an equally rapid policy response, led by enormous fiscal stimulus and facilitated by unprecedented monetary easing. Central banks have bought bonds at a $1tr per month pace, with the US Federal Reserve in the vanguard. Many central banks have embraced QE for the first time, including Canada, Australia and several emerging economies. The Bank of Japan’s experiment in “yield curve control” has spread to Australia, and may well spread further. And central banks have extended further into private sector assets, with the Fed again leading the way by including sub-investment grade bonds in their corporate purchases.

G4 central bank bond purchases

Source: Bloomberg as of 4/22/2020

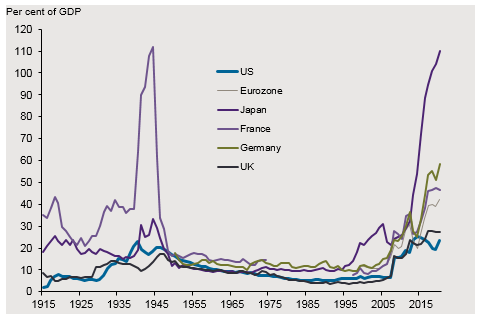

With the close coordination between fiscal and monetary easing, we think it is fairly clear that central banks are monetising the huge fiscal deficits necessitated by the crisis, even as they mostly will not describe their policies in this way. We also expect much of the monetary expansion used to fund these deficits will be very long-lived, if not permanent. The experience of previous large monetary expansions is that the ratio of central bank assets to GDP tends to normalise through rising GDP rather than falling central bank assets. Indeed, after the last recession, only the Fed made a serious attempt to reduce its crisis-era bond holdings, and even that “Quantitative Tightening” was a disruptive process which was halted sooner than expected.

All that said, we think fears that “helicopter money” will lead to a surge in inflation are overblown for now. Central banks typically have an inflation target, coupled with a requirement to support growth or employment. The real concern about monetary financing comes when the central bank’s objectives are subjugated to the government’s. Especially, when rising growth and inflation would call for a tightening of monetary policy, but the government would not be able to cope with higher funding costs. These are the circumstances that can lead to a spiral of ever-rising inflation.

The present situation is very different. Unemployment is set to increase to levels unseen in modern times. This will bear down on inflation, which was in any case quite subdued before the onset of the crisis. The collapse in oil prices will do the same. There are clear risks of long-lasting damage from the recession through corporate bankruptcies and labour market hysteresis. Along with the healthcare response, aggressive fiscal easing to support private sector incomes during the lockdown is the main tool to prevent this damage. It is hard to see how central banks could hope to meet their inflation and growth objectives without facilitating this government spending. Far from being in conflict, the central bank and government objectives are one and the same at this point.

As is often the case, Japan provides a useful example here. The Bank of Japan has been hoovering up Japanese government bonds for years, taking its balance sheet as a share of GDP to levels previously seen only in war time. Yet it is difficult to argue that monetary policy has been too loose in Japan, when inflation is still hovering barely above zero. With nominal demand so subdued, there has been no conflict between keeping government financing costs low, and the Bank of Japan’s inflation target.

Central bank balance sheets

Source: Bloomberg, Major Central Banks as of 4/22/2020

The more interesting questions about monetary financing will come once the crisis has passed, and huge government deficits are no longer needed. It is very difficult to bring down government deficits from very high levels. In the aggregate, advanced economy fiscal deficits have never returned to the levels prevailing before the 2008 financial crisis, and even the journey back to current levels was very painful for many countries. The principle that governments can support private sector incomes with central banks buying the resulting debt has been established. While entirely appropriate to this crisis, it may prove quite inflationary in a milder downturn. But these are concerns for another day – for now, we expect bond markets to remain quite sanguine about the shift to monetary financing, until there are signs that the economy is emerging from the downturn.