The Group of 20’s stated goal is “strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive growth.” Amen to that. The quality-of-life triple threat of low productivity, unfavorable demographics, and stifling income inequality would all be licked if the G20 achieves that goal. The challenge of course is how to get there. Policy makers, economists, and the group itself all fall back on the tried-and-true prescription of “structural reforms.” That catch-all phrase is prominent in their publications, but one usually has to dig deep to uncover the specifics of what, really, these folks are recommending. For the US, infrastructure investment, tax reform, and regulatory reform—to the extent they rigorously address inefficiency, productivity, or inequality—would all count. Today, however, I want revisit in more detail a different proposal that I’ve discussed in the past, and expand on it with three key charts from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

In short, a wholesale change in the US approach to childcare could have a profoundly positive impact on growth and quality of life. The idea is unusual, in that it is motivated by two factors which are often in conflict but here are aligned: first, a clinical focus on key macroeconomic outcomes, and second, deferential attention to small-scale outcomes for human individuals which improve the opportunities, incentives, and quality of life for families in the economy. The result could unlock significant gains in both productivity and hours worked, while at the same time counteract rising inequality—the three keys to sustainable and inclusive growth.

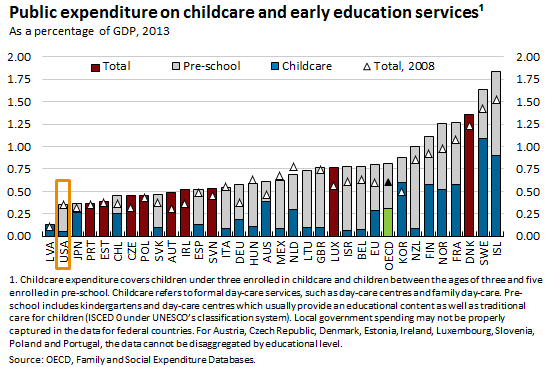

The United States government spends the second-least on preschool and childcare of the 32 individual countries plus the EU, measured as a whole, studied by the OECD:

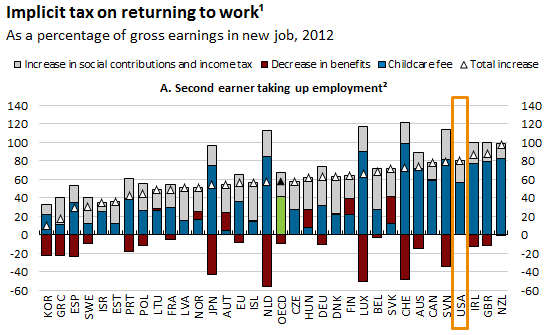

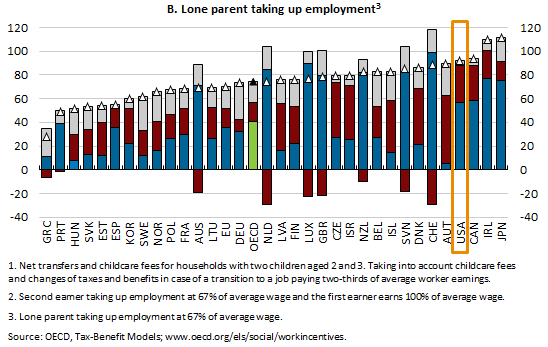

When parents consider re-entering the workforce, childcare costs are a significant deterrent to doing so. For single parents, as well as the second earner in a two-parent household re-entering the workforce in the United States, the implicit tax rate is the fourth-worst in the OECD. It totals some 80%+ of gross pay just for taxes, childcare, and benefit reductions:

The result is an inefficient system, where primary caregivers are compelled to provide in-home childcare in lieu of participating in the wider economy. The impediments persist as children grow and their care needs are only partially met by primary school, with summer holidays and significant portions of the traditional workday hours still not covered. Parents are forced to accept jobs which can accommodate a certain schedule, rather than jobs which allow them to maximize their productivity, earnings, and participation in the economy.

If the United States treated childcare like public education, where every parent who wished could enroll their children in all-day, enriching childcare at little or no out-of-pocket cost, the economic benefits on both a macro and micro scale could be substantial:

- Job creation: the many primary caregivers who are talented and passionate about the work could do it professionally (and this is a job that is not easily automated!). The infrastructure needs on an upfront and ongoing basis are also potentially significant, requiring skilled construction work, regardless whether the programs are publicly or privately administered.

- Increased labor force participation and hours worked: the implicit “re-entry tax” would be removed as a serious disincentive to join the labor force and barrier to pursuing new skills training.

- Increased productivity: individuals, as they see fit, can pursue jobs to maximize their quality of life, earnings, and contribution to the economy, at a level greater than the (purely monetary) cost of caring for 1.9 children per day, which is the average number of children under 18 in each household with children.

- Decreased inequality: childcare is a benefit for all families, paid for by the existing progressive tax system.

- The first four are dispassionate assessments of the raw 1st order macroeconomic effects, which would be critical to justifying the expense and helping pay for it over the short term, but there is a bigger issue at the heart of the proposal with longer-term implications. Providing all children with equal access to robust early childhood education, reliable care, and a structure through which other basic health and nutrition needs can be met efficiently and consistently will help strengthen the youngest generation of Americans. They are the future US economy.

Clearly any program like this, whether it’s done with physical structures, extensions of the public education system, or through vouchers and refundable tax credits would be costly. However, the realistic potential growth uplift outlined above allows “dynamic scoring” to be used with confidence for at least partial self-funding. Dynamic scoring uses future growth expectations, realized in the form of higher tax revenues, to fund current expenditures. The concept is frequently abused because growth forecasts are too optimistic, but in this case the pure economic effects are pretty simple. Near term funding through progressive taxation can provide a plausible bridge to a period of sustainably higher and more inclusive growth. Higher sustainable growth with less inequality allows a larger share of the economy to eventually make meaningful tax contributions. The ability of the economy to sustain less progressivity in the tax code ought to be a “win” for both political parties.

Any structural reform which can plausibly create jobs, increase labor force participation, increase productivity, and reduce inequality would produce meaningful progress toward “strong, sustainable, balanced, and inclusive growth.” Reforming the childcare system could potentially do all of this, while encouraging participation and engagement in the economy by all parents who wish to do so.