While any new trade laws would require congressional support, the President can impose tariffs for unfair trade practices or national security reasons. However, tariffs are often negotiation tools, and the actual levels may be lower or more limited than initially proposed due to their impact on U.S. inflation and growth.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the Russia-Ukraine conflict exposed supply chain weaknesses, leading to more friendshoring and industrial policies globally. President-elect Trump’s victory and his tariff plans could accelerate these changes. While any new trade laws would require congressional support, the President can impose tariffs for unfair trade practices or national security reasons. However, tariffs are often negotiation tools, and the actual levels may be lower or more limited than initially proposed due to their impact on U.S. inflation and growth.

A 60% U.S. tariff on Chinese goods could lower China’s real gross domestic product (GDP) growth by 2 percentage points over the next 4-6 quarters, assuming all other factors remain constant, according to J.P. Morgan Economic Research (as of November 2024). Exports, investments and consumption will face direct negative impact, alongside the spillovers from reduced business confidence. To offset this impact, China’s government will likely increase fiscal support and may respond with retaliatory tariffs and currency depreciation.

Trade tensions are a familiar challenge for Chinese exporters. While their share of U.S. imports has fallen by 5 percentage points since the end of 2017, their share of global exports has increased. Chinese exporters have been managing geopolitical risks by diversifying export destinations and increasing production capacity in other EMs to counter tariff measures. They have become less dependent on the U.S. and are better equipped to handle tariff escalations compared with 2018.

Products from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and Mexico have increased their share of U.S. imports since 2018, partially offsetting the shortfall from China. ASEAN has mostly replaced China in light-manufacturing products like textiles, Mexico in the automotive sector, and Taiwan and Korea in electronics. Whether this trend continues will depend on future tariff levels, the specific products targeted and any transshipment restrictions, such as those related to Mexico-manufactured autos. Several factors will determine the winners in the reshoring trend: cost competitiveness, supportive government policies, close substitutes for Chinese products and integration into existing supply chains, as well as adequate infrastructure and capacity to meet additional demand. Evidence from 2018-2019 suggests these beneficiaries not only re-exported Chinese goods, but also increased value-added production and exports to economies beyond the U.S. This was likely due to expanded capacity allowed for economies of scale and new trade opportunities with other economies.

In conclusion, supply chain diversification has been underway for years, and higher tariffs on China could accelerate this process, especially for strategically important goods like semiconductors, solar cells and critical metals. This shift will benefit other low-cost manufacturers, but if the Trump administration raises tariffs on all imports, reallocation could slow and lead to higher costs. While U.S.-China trade connections will become less direct, a complete decoupling is unlikely in the near term. Firstly, the exact scope and magnitude of tariffs remain uncertain. Secondly, China remains an attractive manufacturing hub due to its competitive advantages, economies of scale and sunk costs that firms must weigh against the benefits of reshoring. Additionally, Chinese companies are better positioned to cope with higher tariffs than they were before.

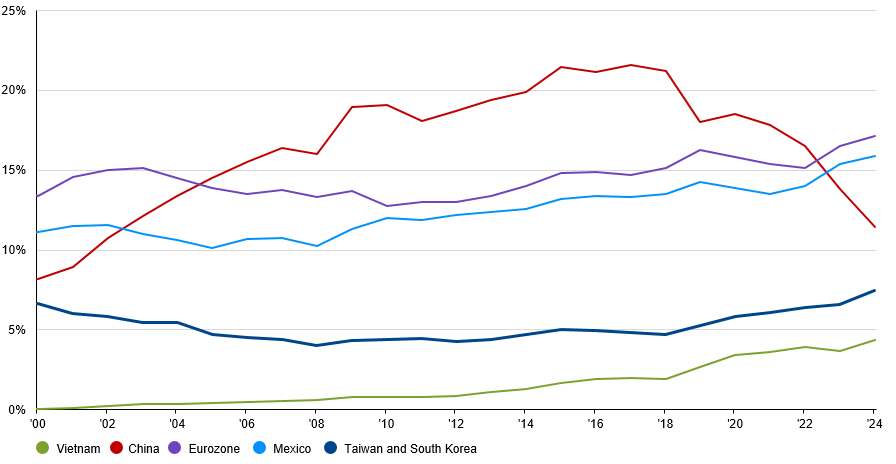

Mexico and several Asian markets have increased their share of U.S. imports since 2018, partially offsetting the shortfall from China.

Exhibit 5: U.S. goods imports by market

Share of total U.S. goods imports