[START RECORDING]

FEMALE VOICE: This podcast has been prepared exclusively for institutional, wholesale professional clients and qualified investors only as defined by local laws and regulations. Please read other important information, which can be found on the link at the end of the podcast episode.

MR. MICHAEL CEMBALEST: Morning everybody and welcome to the October Eye on the Market. This one’s called Reruns, because there are three topics that I’m covering here that for investors are things that we’ve seen before or thought about before, talked about before. First one is on US equity markets, the second one is on the clash between US and China, and the third one is on renewable energy.

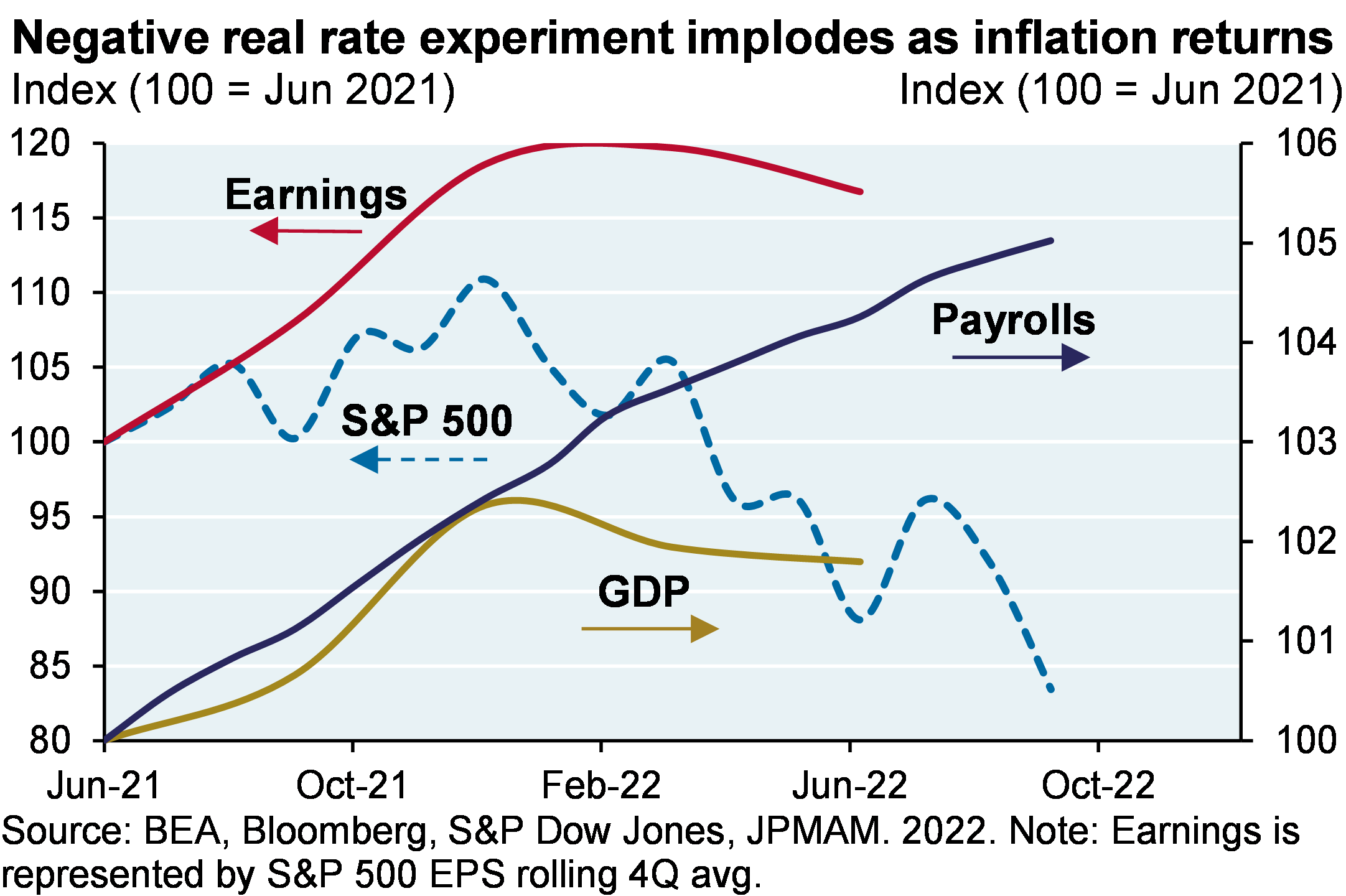

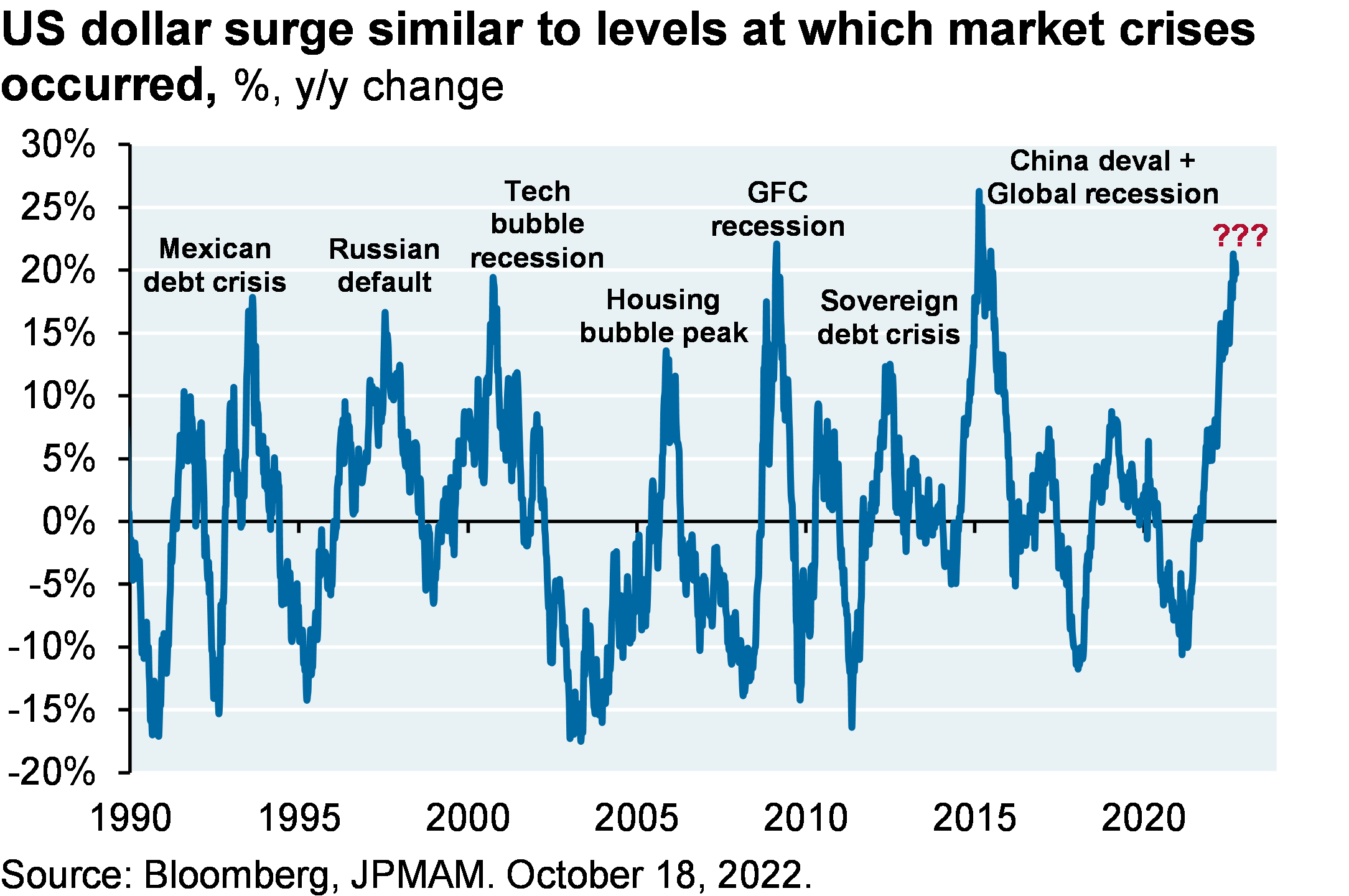

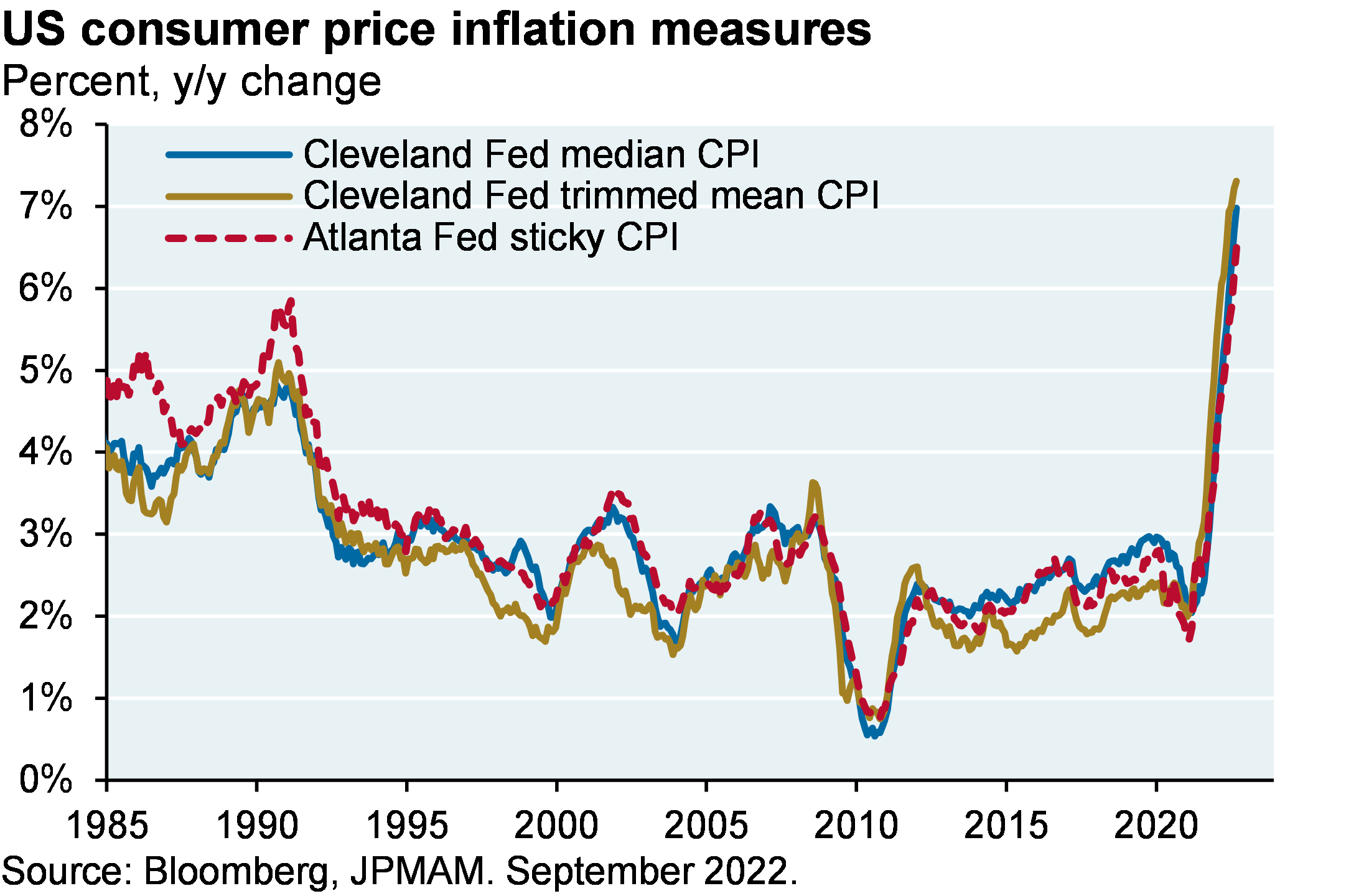

So let’s talk about equity markets first. When bear markets happen and the investment mistakes of the prior cycle get revealed, all of a sudden you tend to see bearish investment commentary intensify. And it’s almost like there’s a confessional aspect to some of this research, as if the people that write it are trying to atone for having missed some of the signals and risks during the prior cycle.

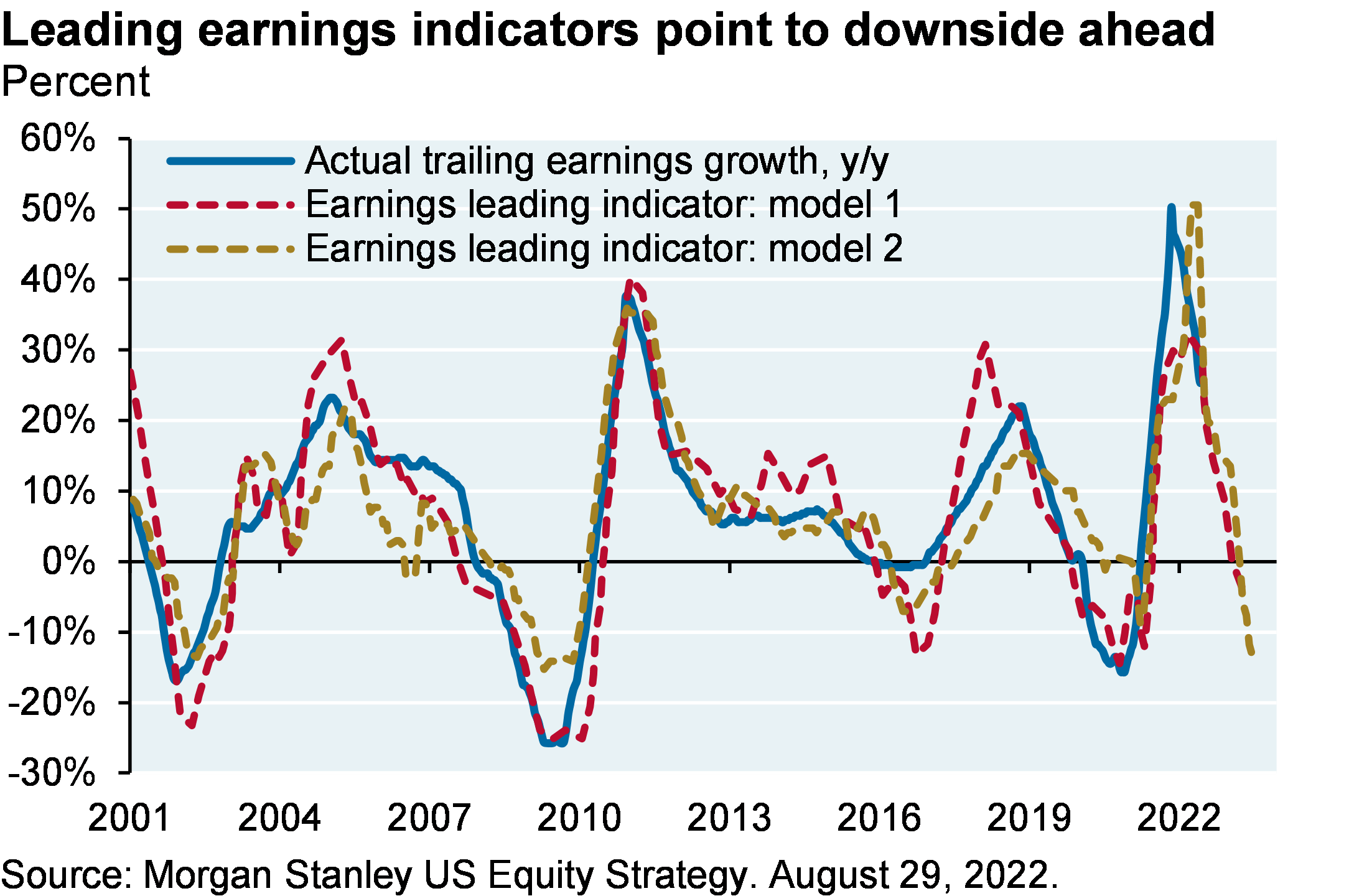

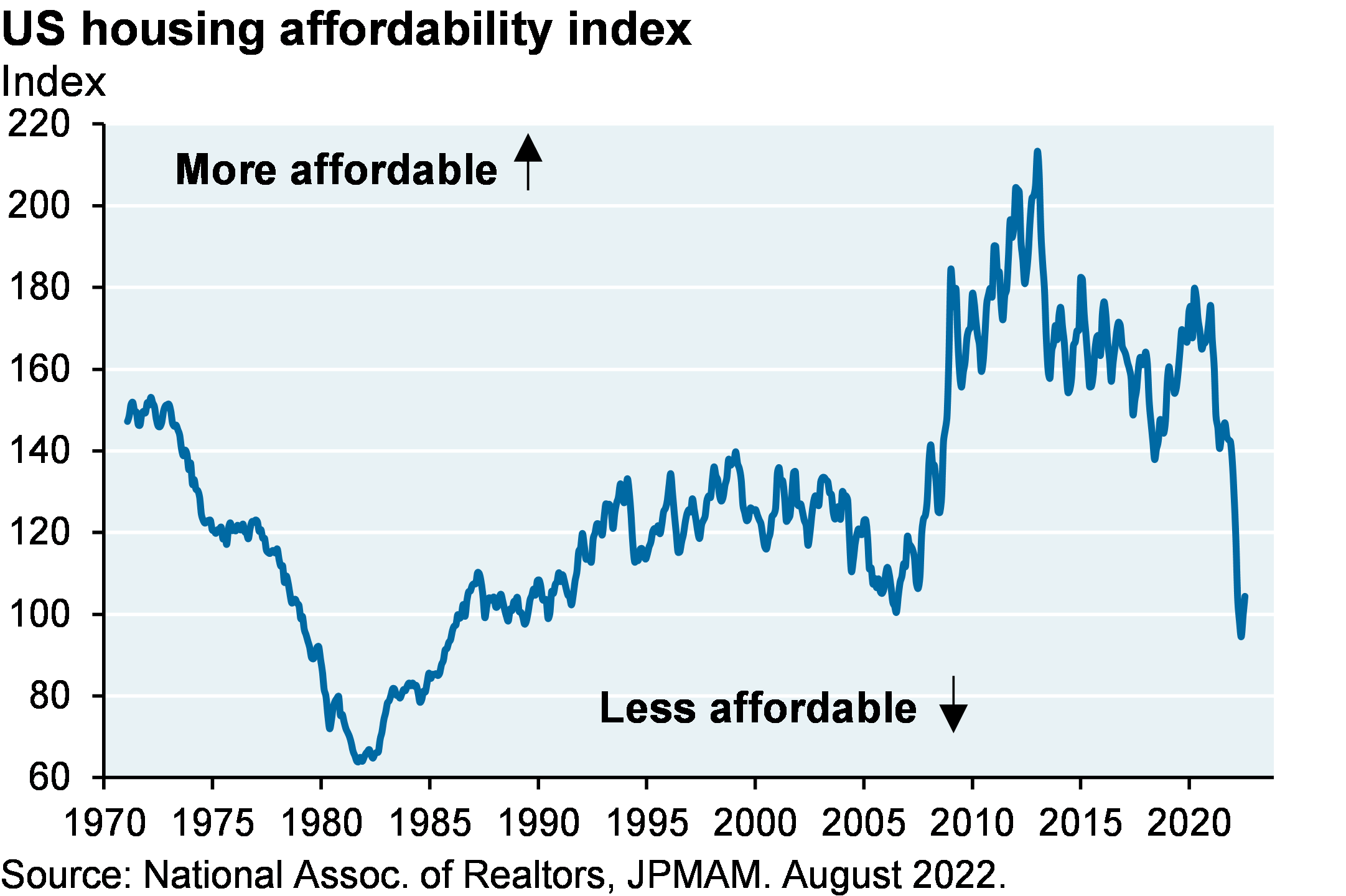

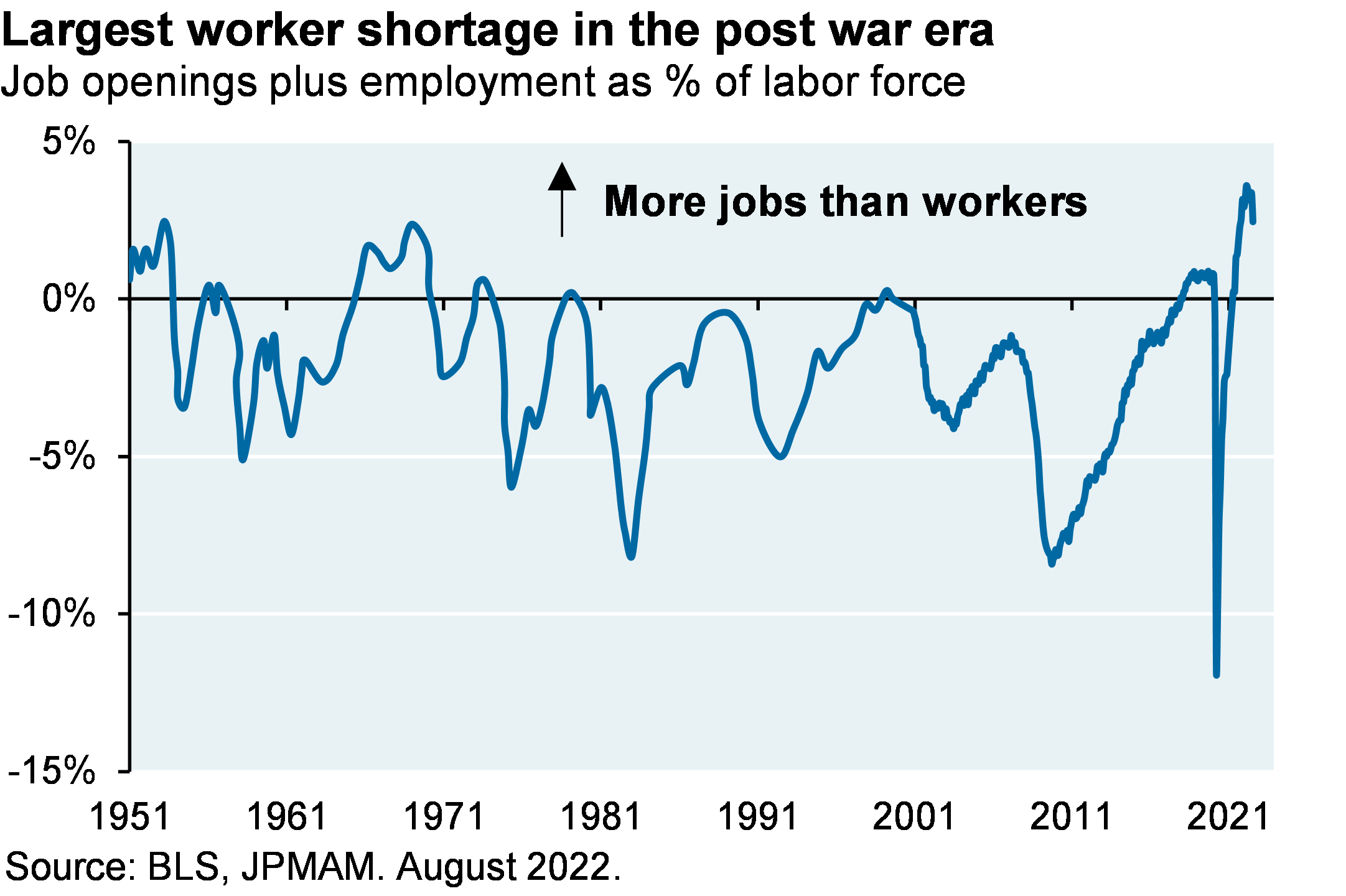

And I read a lot of research, maybe 1,500, 2,000 pages of research a week. And there’s a very consistent message right now that’s very bearish on earnings, valuations, inflation, central bank policy, housing, trade, energy, the surge of the dollar. I’m not saying that these things don’t matter, of course they do, we’ve been talking about them for a while. But at some point, the more markets go down, you have to start to shift your focus from the risks to the cycle to the shift in the cycle. And look, we spent a lot of time talking about young unprofitable companies, Fed mistakes, garbage SPACs, crypto, metaverse, et cetera, 18 months ago. But by the time a lot of assets reprice, it’s time to start shifting our focus towards where things go from here.

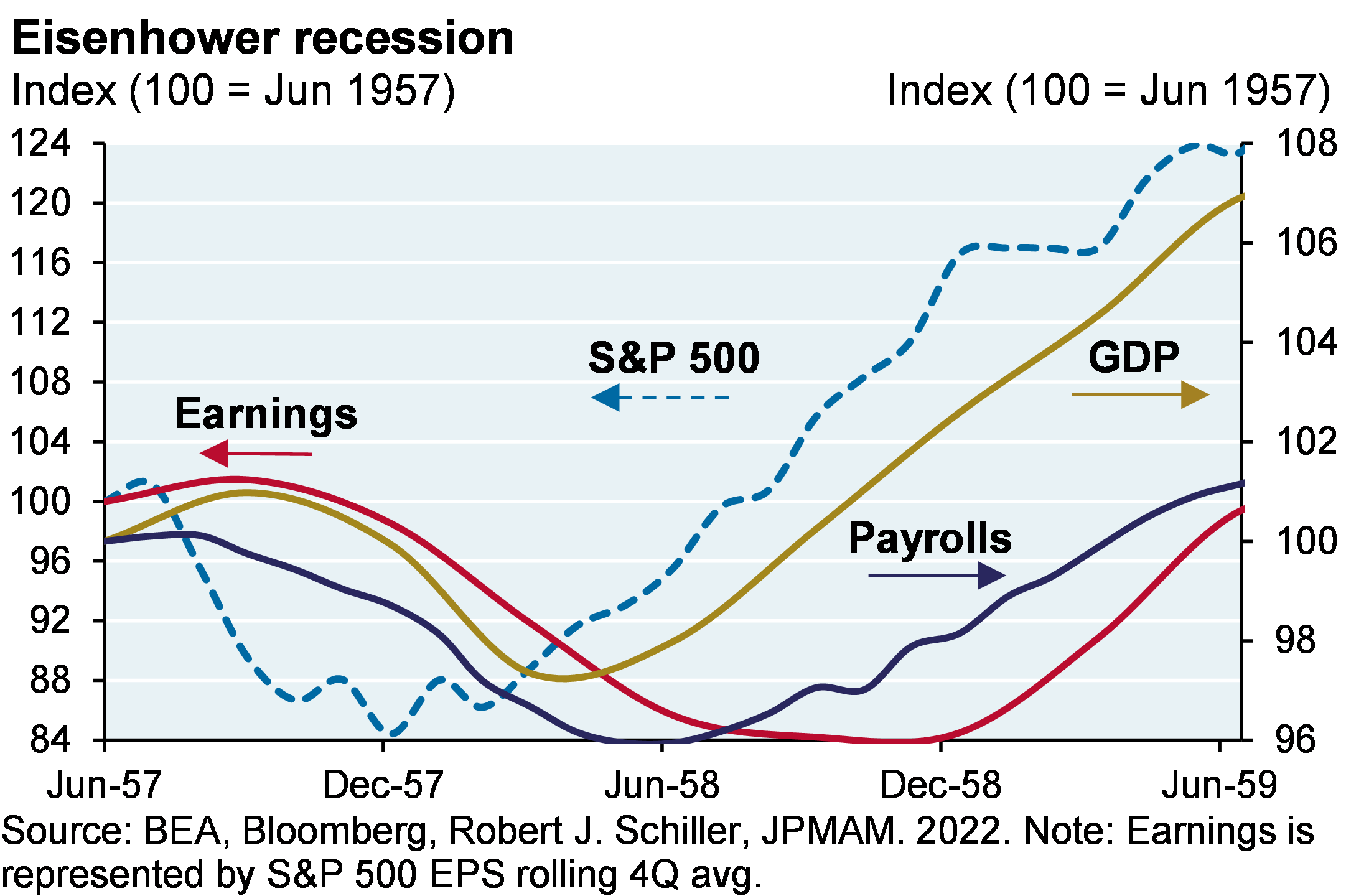

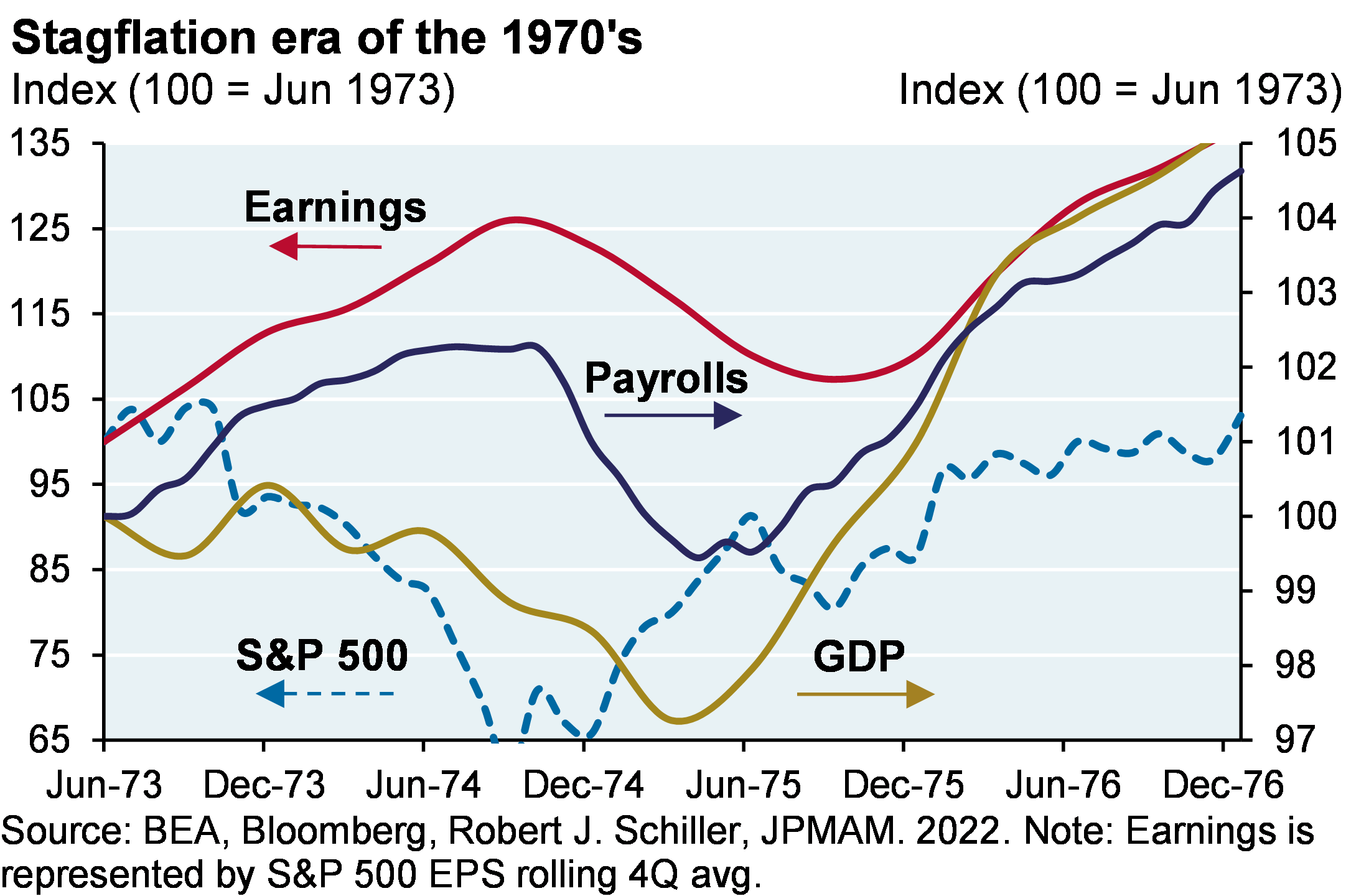

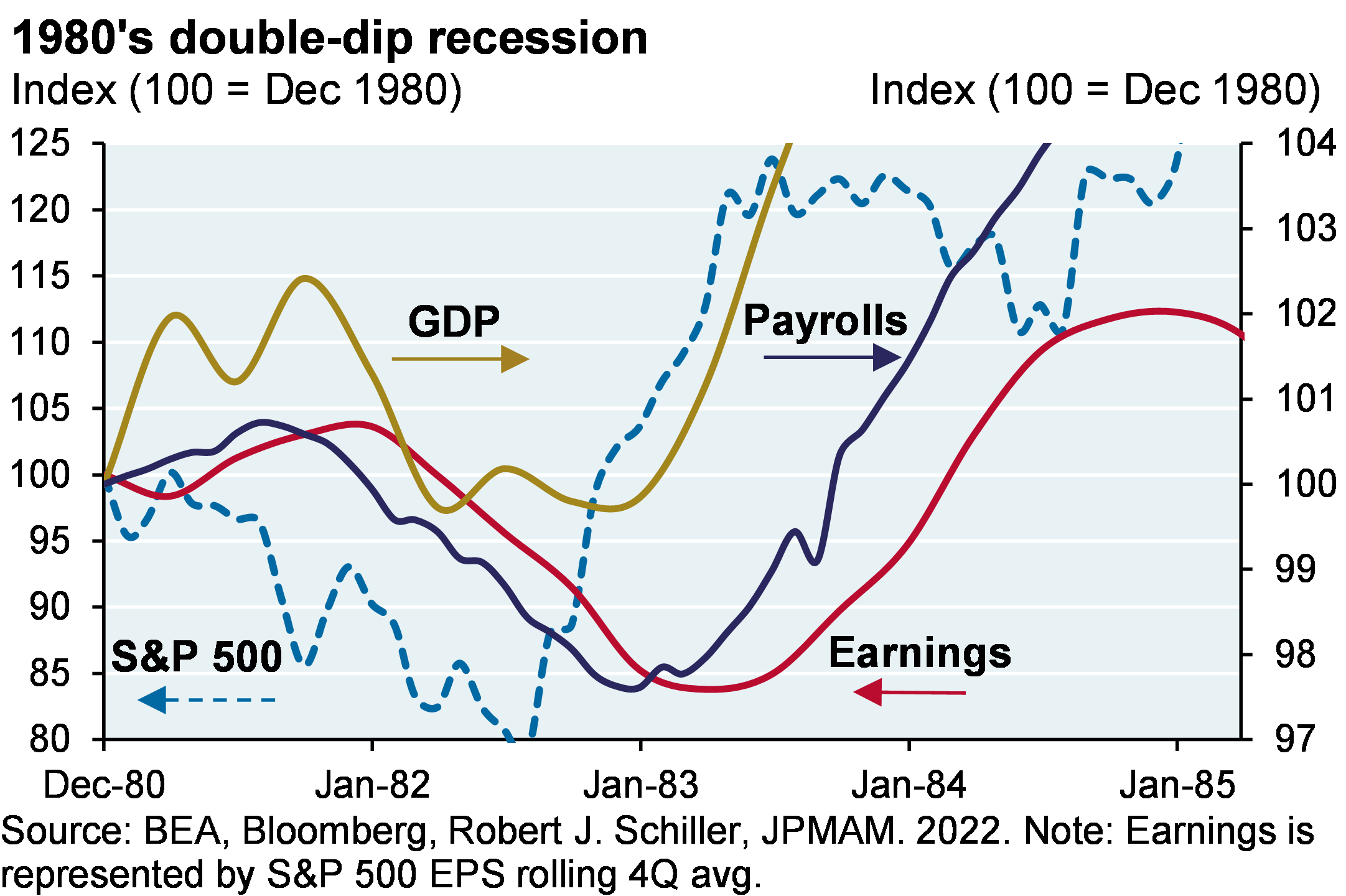

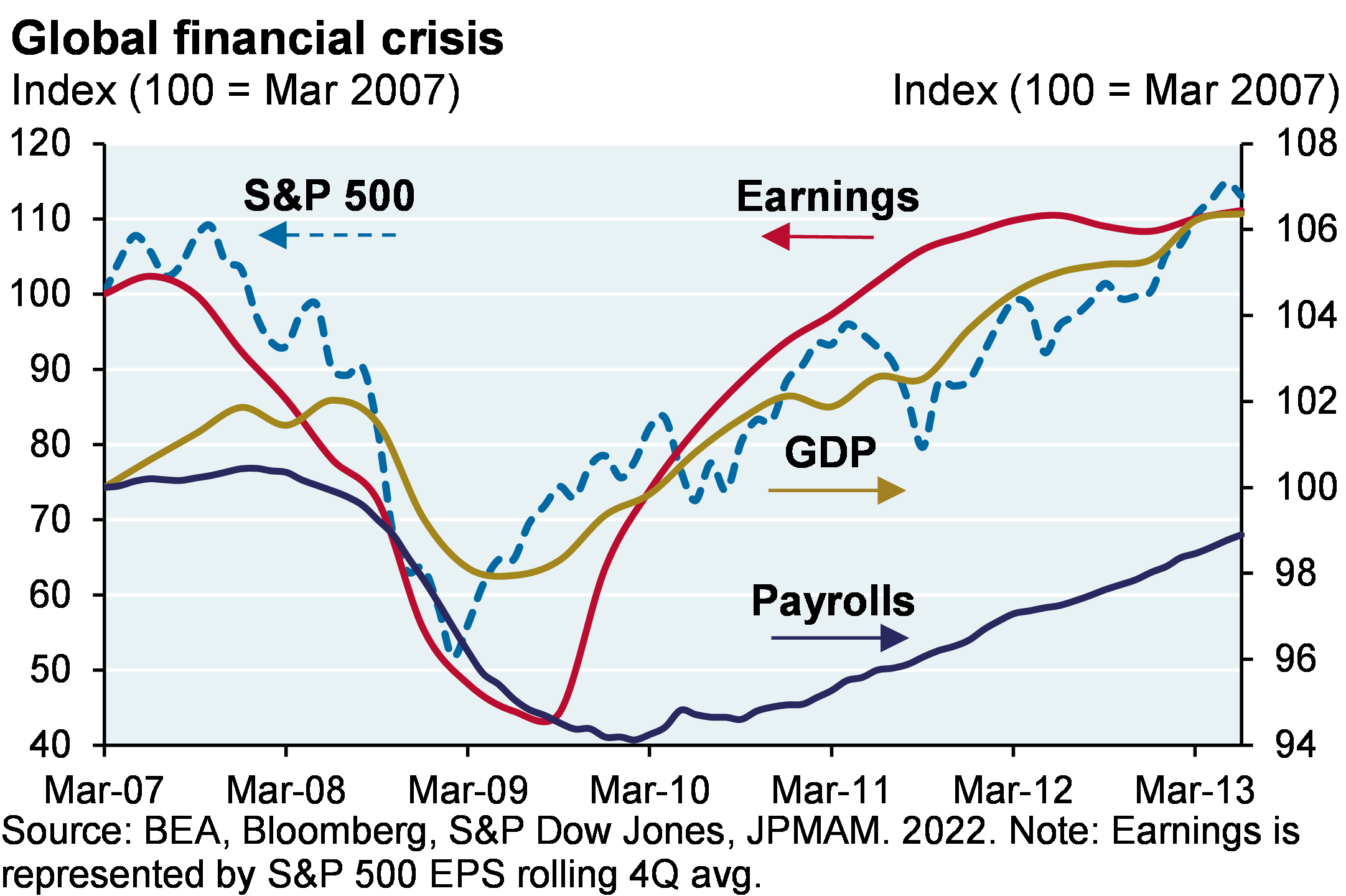

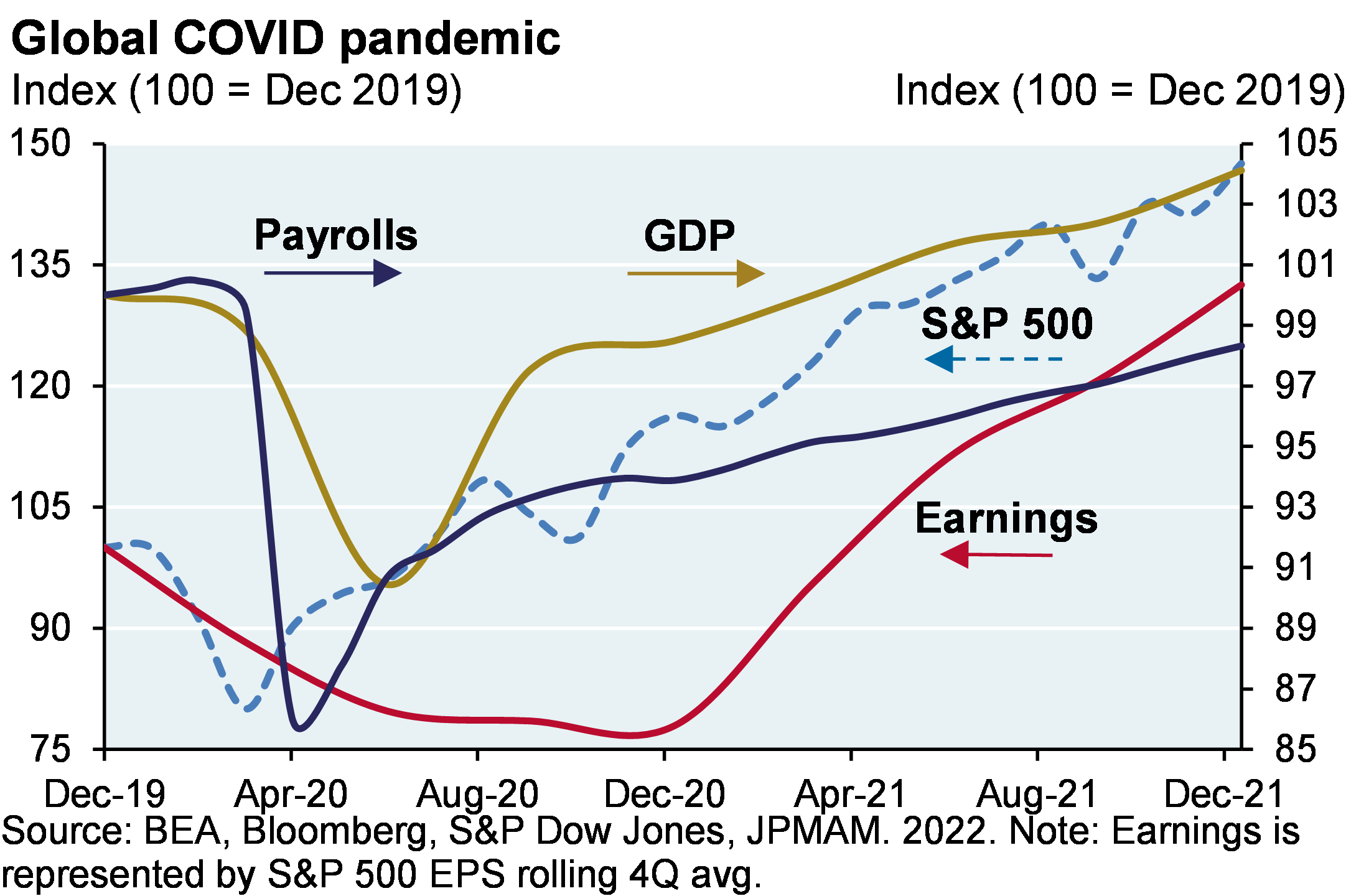

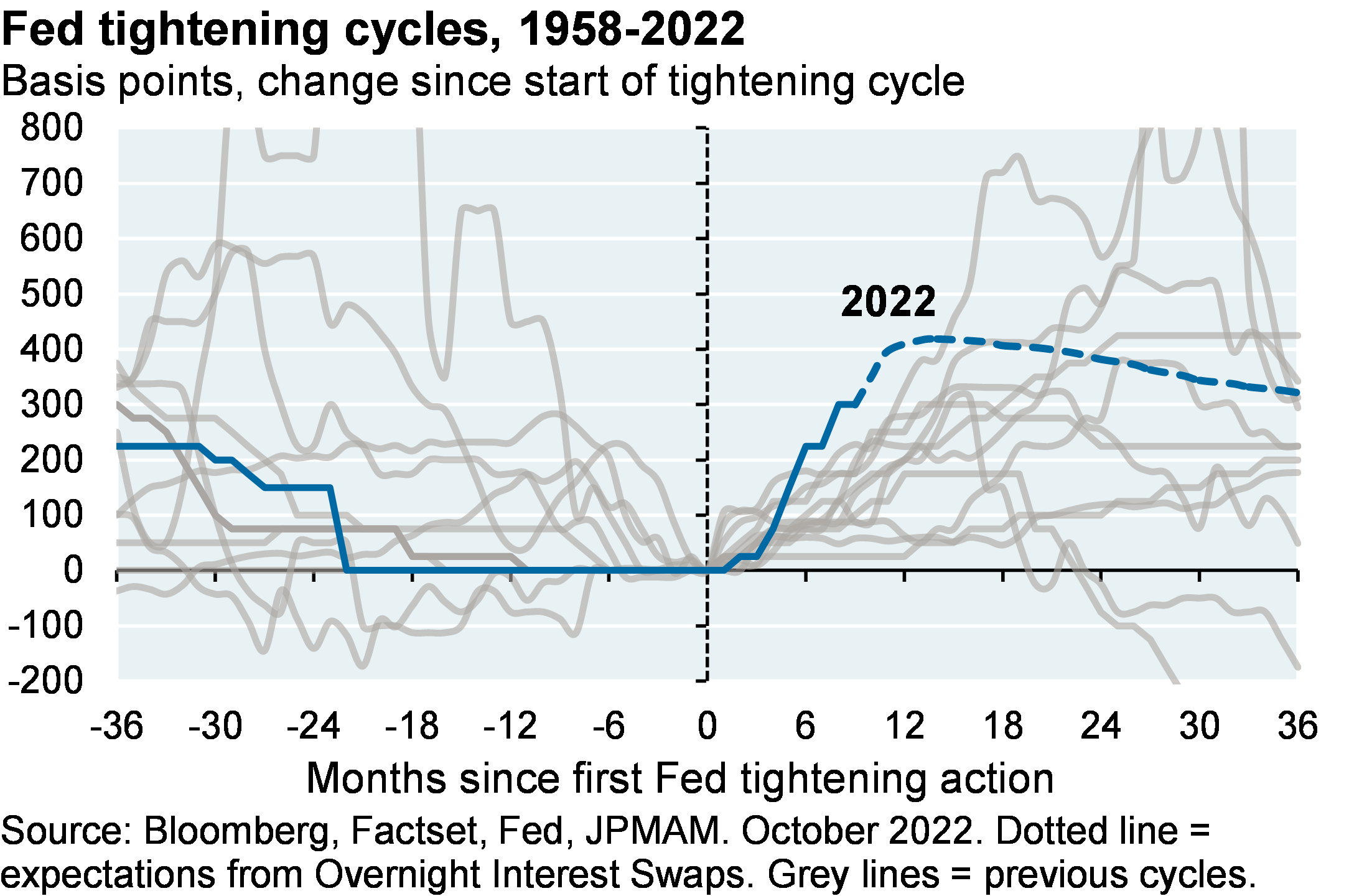

And that’s why I wanted to show a whole bunch of these charts. There’s a remarkable consistency. Equities tend to bottom several months, at least, before a lot of other things do during recessions. And I certainly do think the chances of a recession are quite high over the next few quarters, given what going on with Fed policy.

But let’s take a look at some of these things and start with the Eisenhower recession in the 70s, which was a pretty severe one, and also had not a lot of monetary and physical air drops associated with it. Equities bottomed in December in 1957, and GDP bottomed six, seven months later and then payrolls and then earnings bottomed. And by the time a lot of those GDP and payrolls and earnings and things like that were getting better, the equity markets were already up pretty substantially.

And so there’s a bunch of charts in here for the, as I mentioned, the Eisenhower recession, the stagflation era of the 1970s, the double-dip recession in the 80s, the S&L crisis in the 90s, the global financial crisis 12 years ago, and then the COVID pandemic. In each one of these, the patterns were the same. The equity markets go down first, and then a whole bunch of things go down later.

And so I just want to make sure as investors, that we and you are focused on the equity markets and how they tend to discount in terms of time and magnitude, the declines and other things. So we’ll be following payrolls and we’ll be following the decline in earnings, which is certainly coming, and we’ll be following the decline in GDP. But it’s very important to understand that in almost every cycle, the decline in equity markets predates that by quite a bit.

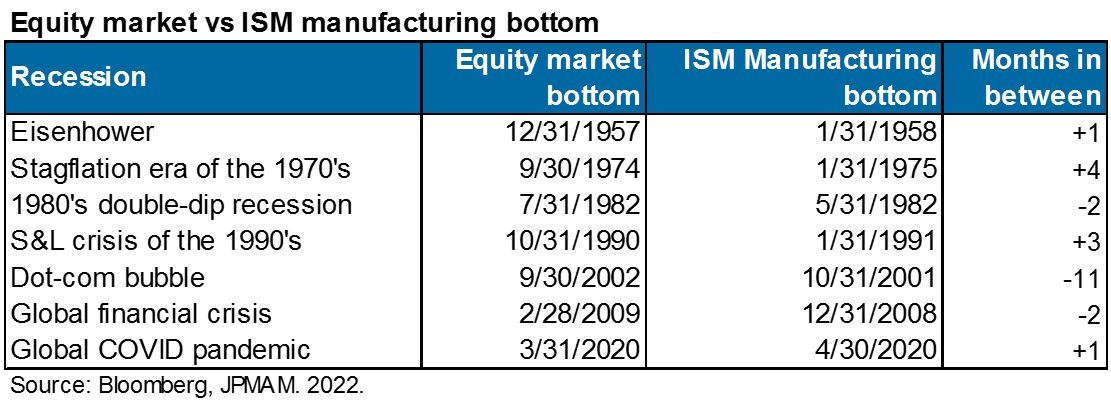

And if we had to pick a single variable that does coincide with the bottom in equity markets, it happens to be the ISM manufacturing survey. We’ve talked about this before. If there were any one variable that you had to hang your hat on, the ISM has the closest coincident timing with the bottom in equity markets. And in most cycles, they bought them together within one or two months of each other. The only exception here was the dot-com bubble, recession collapse, where everything was all mixed up. The equity bottom actually happened after the recession and after the decline in earnings. So that’s the one outlier here.

But I have no reason to believe that this cycle is going to be very different from the other six of them. So we’ll be watching the ISM survey closely, has a really good track record of coinciding with equity market bottoms, and I would consider something like 3,200 to 3,300 on the S&P index if we got there sometime this fall or winter, pretty good value for long-term investors.

The second rerun topic is the US and China. And what I mean by rerun is there was a book by Graham Allison. I forgot what year it was written, but it was called The Thucydides Trap. And it had to do with how rising empires compete for power with incumbent empires. And by his account, in 12 of 16 historical examples, competing empires end up in military conflicts with each other. And obviously he’s writing this book as a parallel to the current US/China relationship.

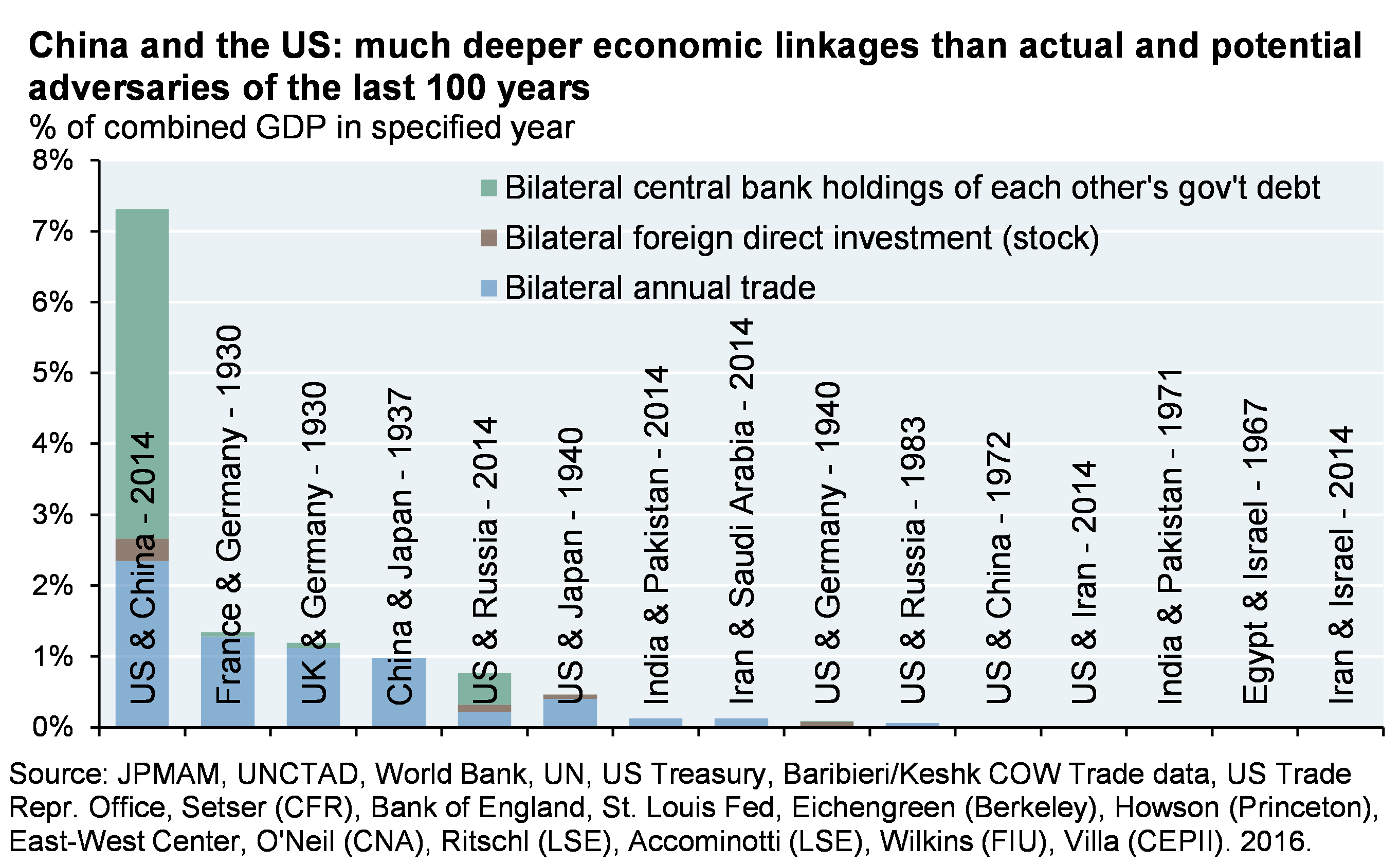

I published a chart at the time when the book came out showing the economic ties between the US and China through bilateral central bank holdings, foreign direct investment and trade that were much higher than all sorts of historical examples. And my chart was meant to highlight how these unique economic ties between the US and China were different and could end up with a different outcome.

And as things stand now, there are certain aspects of the US/China relationship that are still supporting that general thesis. In 2021, despite the Trump tariffs, the US imported $540 billion of goods from China, which was almost the same as the pre-trade war peak in 2018. And China still holds about a trillion dollars of US treasuries and agencies.

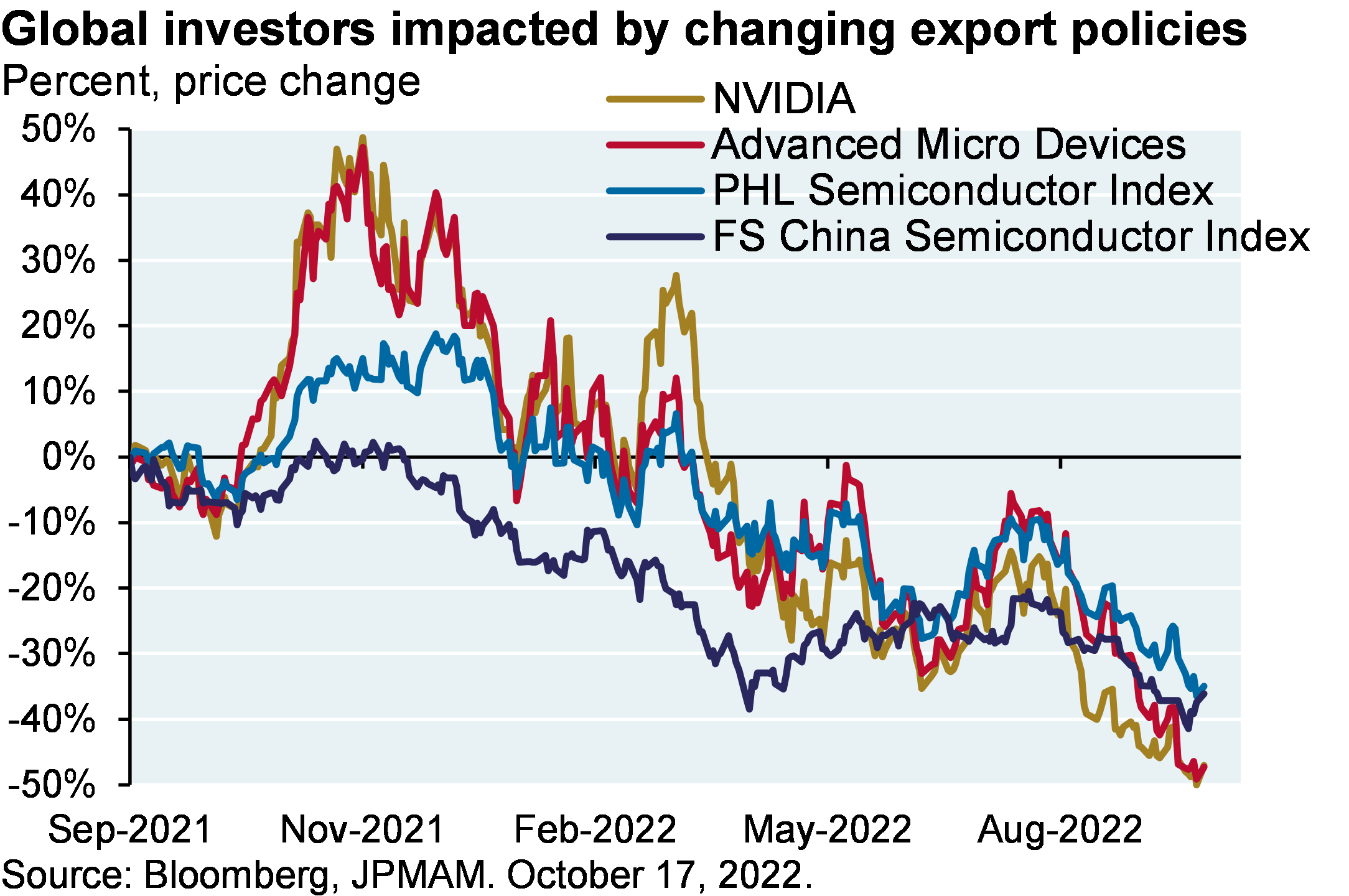

So certain aspects of the US/China relationship are still intact. Obviously others are not. There’s been a lot of things changing about the Committee for Foreign Investment in the United States and all sorts of policies affecting bilateral flows. And the latest salvo from the US is probably the way that a lot of people see it who watch this stuff closely, the most comprehensive change in US/China trade policy in decades, and it has to do with semiconductors.

So when you look at what the Trump Administration did and the steps they took against Huawei, they left open the possibility of future engagement maybe in exchange for Chinese cooperation on other geopolitical areas. But these latest moves by the Biden administration may close those doors for quite a long time.

So there are four interlocking elements of this new policy, and they all have to do with semiconductors, and specifically the high-end, high-performance semiconductors, where the US has a strategic advantage over China. So the elements of this new policy are to impede China’s artificial intelligence industry by restricting access to high-end chips to block China from designing those chips domestically by cutting off access to our chip design software, to block China from manufacturing the chips by cutting off access to semiconductor manufacturing equipment, and then to block China from producing the equipment by cutting off access to components. So it’s a pretty comprehensive policy.

And essentially what the policy states is that high-end chips can no longer be sold to any entity operating in China, whether it’s the Chinese military, a Chinese tech company, or a US company operating at a data center in China. And export licenses will be needed and according to the Department of Commerce, a lot of these requests are going to be subject to the presumption of denial.

And so we go through a little bit more of the details here. There’s an excellent piece from the Center for Strategic and International Studies that goes through a lot of the details, and we summarize that here. The bottom line is that some of the new policies are pretty restrictive. Any chip manufacturing operation anywhere in the world that seeks to build high-end chip designs will end up, may end up losing its access to US semiconductor, manufacturing, equipment, support, advice, repair, et cetera.

So this is a pretty big deal. Some of the policies only apply to super-high-end chips, but the performance standards are being held constant. So over time, more and more of the semiconductor markets going to be subject to these restrictions. And when you read the comments from National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan, it makes it pretty clear that the US is looking at these kinds of things as a new strategic asset in the US toolkit, which he describes as imposing costs on adversaries and even over time, degrading their battlefield capabilities.

And what’s up next, there’s talk of restrictions on US entities investing capital in Chinese technology companies as the focus shifts from the transfer of technology to the transfer of capital. We wrote a paper in our institutional business. We have a strategic advisory investment committee and we write one or two papers a year, and the last one was on de-globalization. And this certainly is another element in the de-globalization, in the gradual de-globalization that’s taking place, all of which has the potential to raise the cost of goods and services in places that are trying to now rebuild and re-onshore all sorts of production and supply chain capability.

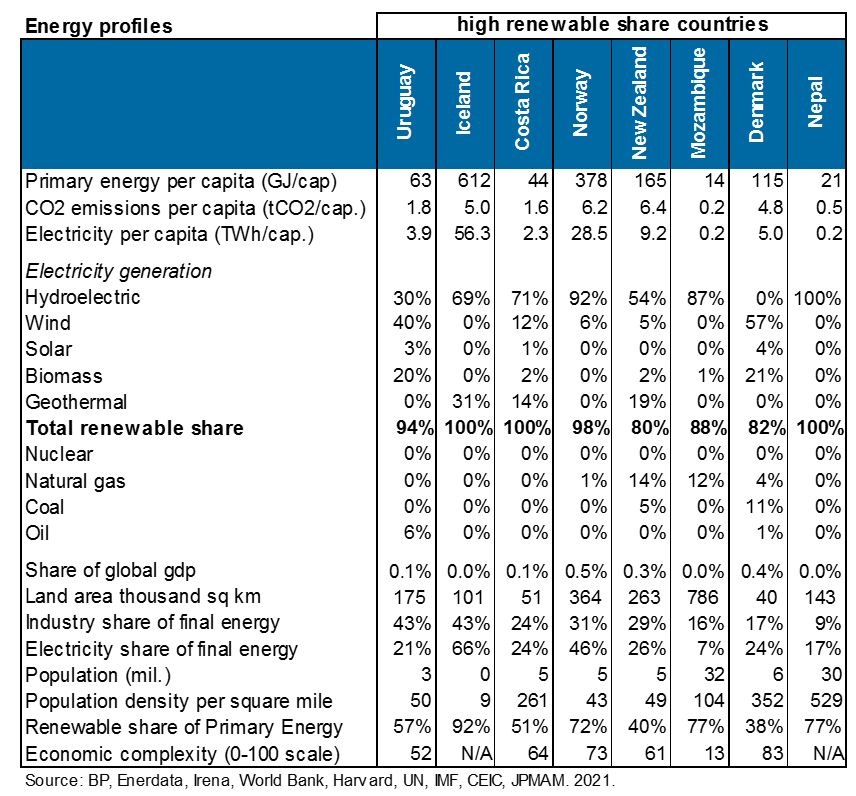

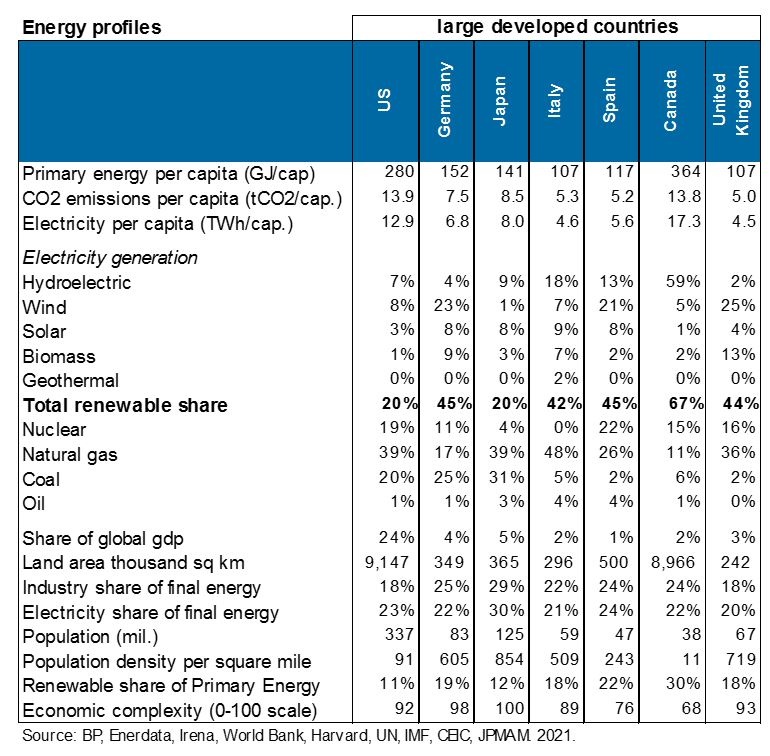

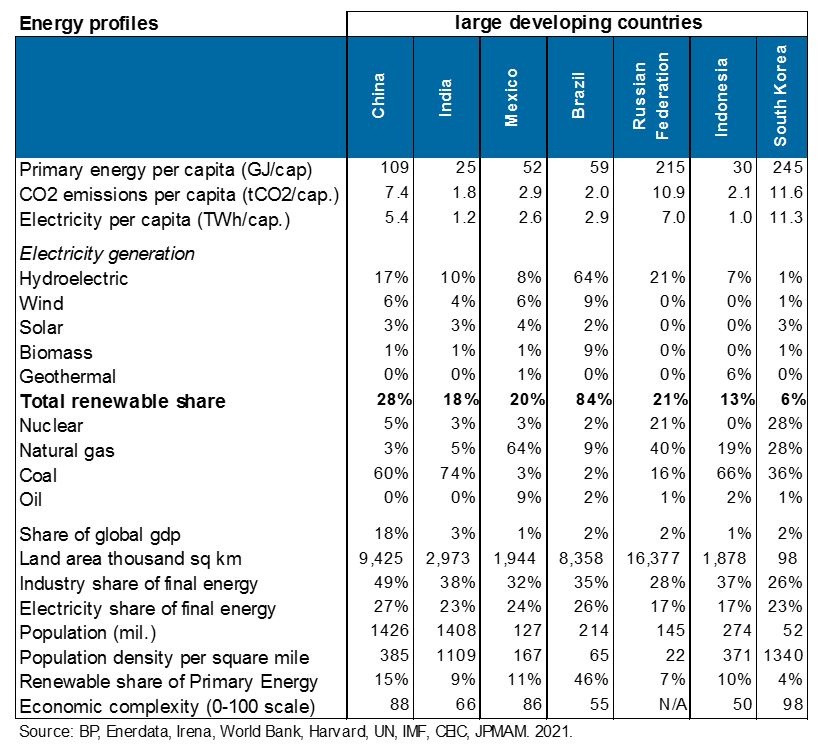

The last rerun topic is on renewable energy and what I’m calling the Pitcairn problem, which are press articles that you see all the time on tiny countries that have very high shares of renewable power generation, mentioning them as paragons of the future that are leading the way on sustainability, without mentioning any of the factors that limit their relevance for everybody else, and specifically for the larger developed and developing economies.

The latest example of this is a piece in The New York Times on Uruguay, which was a great read and very interesting. The problem is it was completely missing, as these articles usually do, the broader context of how to understand countries like Uruguay, Iceland, Norway, Costa Rica, and other similar tiny places in terms of how they’re getting these high shares of renewable power generation.

So first of all, most of these countries tend to have very small shares of global GDP, very small populations, and low population density. They also tend to have lower economic complexity, which measures a country’s ability to produce a wide range of goods and services. That means they need less developed energy systems.

They also tend to be pretty small in terms of land area, which is a very important consideration when you think about the transmission investment required to bring wind and solar power to where the load centers are. So it’s one thing to build wind on the shore of Denmark to power things in Denmark. It’s another thing to build wind in certain places in the United States and have to transmit that to where the load centers are; it’s very different.

But the biggest issues are the ones that don’t get discussed enough. If you find a country that has anywhere, 40, 50, 60, 70% renewable shares, chances are it gets the lion’s share of its electricity generation from hydroelectric power. And most developed, and even a lot of developing countries have already built out their suitable hydroelectric resources, and so it can be very misleading to be talking about these paragons of renewable generation that happen to be small little places with spectacular hydroelectric resources.

Some of the other ones have really unique geothermal resources, like Iceland, Costa Rica, and New Zealand, or they have a lot of sugar cane-based biomass. And the reason that it’s important to specify sugar cane is that sugar cane-based biomass has seven or eight times more energy per unit of investment than corn ethanol does, and Guatemala and Uruguay are examples of that.

So the combination of all these attributes makes this little Pitcairn group of countries much less relevant for everybody else. They’re interesting to learn about. But the big developed and developing countries in the world are pursuing a renewable energy future based not on hydroelectric and not on geothermal and not on sugar cane-based biomass, but on a lot more wind and solar power and maybe some of that being used to produce hydrogen, all of which requires a lot of raw materials, a lot of critical minerals, a lot of project- siting, a lot of transmission investment, and plenty of backup thermal power for when those other things are working.

So more of that on, more of all of this in next year’s energy paper. But I did want you to, everyone to understand the limitations of some of these smaller countries and their relevance for everybody else. And there are some tables in here with lots of statistics that you might find interesting.

So that’s enough for now. We will probably talk to you again after the midterms, which I don’t really expect to be much of a market-moving event compared to everything else that’s going on with the Fed and the pending recession, declining earnings, and everything else. So thanks for listening, see you next time.

FEMALE VOICE: Michael Cembalest’s Eye on the Market offers a unique perspective on the economy, current events, markets, and investment portfolios, and is a production of J.P. Morgan Asset and Wealth Management. Michael Cembalest is the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset Management and is one of our most renowned and provocative speakers. For more information, please subscribe to the eye on the market by contacting your J.P. Morgan representative. If you’d like to hear more, please explore episodes on iTunes or on our website.

This podcast is intended for informational purposes only and is a communication on behalf of J.P. Morgan Institutional Investments Incorporated. Views may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as personal investment advice or a solicitation or recommendation. Outlooks and past performance are never guarantees of future results. This is not investment research. Please read other important information, which can be found at www.JPMorgan.com/disclaimer-EOTM.

[END RECORDING]