PUT CASH IN ITS PLACE

What does it mean to think holistically about investing your cash?

The most effective strategy incorporates a clear investment policy, well-defined goals and parameters for liquidity, quality and return. An essential element, in our view: cash segmentation.

In following this well-established discipline, organizations distinguish among:

- operating cash (requiring same-day liquidity)

- reserve cash (with an investment horizon of six to nine months or longer)

- strategic, or core cash (with an investment horizon of one year or longer)

They can then choose the most appropriate investment solution for each segment.

As markets shift and business needs evolve, cash segmentation has become an especially useful tool for short-term fixed income investors. In the following pages we examine how segmentation should be addressed in an investment policy; how to forecast cash flows and establish the structure of segmentation; and how best to choose an investment solution for each segment of a cash portfolio.

Investment policy

An organization’s investment policy, which defines the objectives of liquidity investment, should guide the framework around cash segmentation. An investment policy will specify what percentage of an investment portfolio must be in cash, list the investment goals, and identify acceptable levels of risk (defining, for example, maximum portfolio duration and the minimum credit rating for a security in the portfolio).

Cash forecasting

Cash segmentation begins with a detailed cash forecast. An organization should first determine what percentage of a portfolio needs to be immediately accessible as cash and what percentage can be viewed as surplus cash. The precise detail captured in that forecast will depend on how much visibility a business has on its cash flows. Ideally, the treasury team should try to ascertain when and where surplus cash is held in the organization, how much of it is available and for how long.

Accuracy is important. If the level of surplus cash is underestimated, then it may not be invested optimally and the organization could miss the opportunity to capture valuable investment returns. Conversely, if the level of surplus cash is overestimated, cash may need to be pulled from investments on short notice, which could lead to realized losses. An organization’s treasury team may also run the risk that it cannot liquidate investments in time to meet business needs and may need to find funding from alternate sources.

As part of the investment process, the portfolio management team utilizes scenario analysis tools to evaluate security and portfolio performance in different environments. This helps determine optimal portfolio positioning on the yield curve and across sectors.

Cash segmentation

In making a cash forecast, an organization should consider if any event could have an effect on the cash position—and then assess its likelihood and timing. For example, a surplus cash position might be substantially increased by a bond issue or sale of part of the business. Conversely, the cash position may be reduced by an acquisition, share buyback or pension funding.

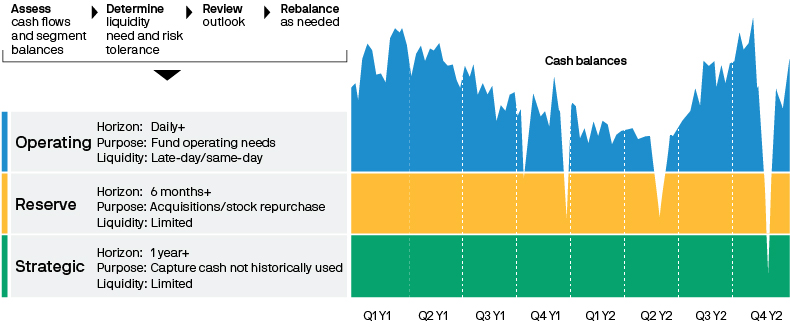

Once a cash forecast is in place, an organization can segment its liquidity portfolio into three categories, reflecting their different liquidity needs and risk profiles (EXHIBIT 1). Operating cash, used to fund an organization’s day-to-day needs, requires late day/same day liquidity. Reserve cash, used for such items as acquisitions, stock repurchase or R&D, does not require same day liquidity. Finally, strategic cash, surplus cash that can accommodate even more limited liquidity, can be invested over a longer-term horizon.

EXHIBIT 1: UNDERSTANDING YOUR CASH NEEDS

For illustrative purposes only

Among the considerations for cash segmentation: What is the purpose of the cash, its time horizon, liquidity requirements and return objectives? Are there any tax or accounting issues to consider? Should segments apply locally, regionally or globally? How, by whom, and how often, will segments be reviewed and rebalanced?

Investment solutions

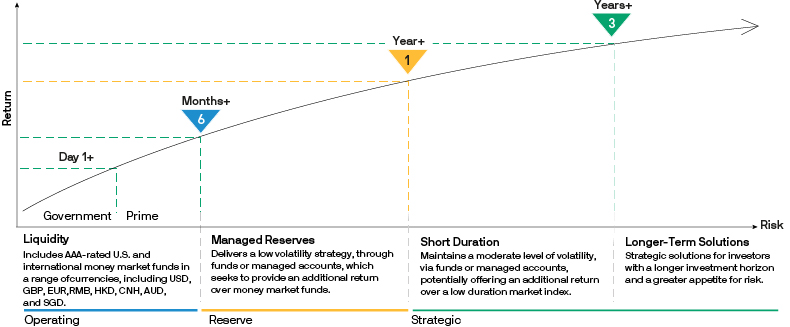

The most effective liquidity strategy will select a specific investment solution for each cash segment (EXHIBIT 2).

Operating cash may be invested in money market funds (MMFs), government or prime, with either a stable or floating net asset value (NAV). Bank obligations, treasuries and commercial paper are other solutions for operating cash requiring same-day liquidity.

Because reserve cash requires limited liquidity, it can be invested over a horizon of 6–12 months, thereby capturing incrementally higher yields and returns than money market funds, while taking on only slightly greater risk and keeping a focus on preservation of principal. A strategy for reserve cash could have a portfolio duration of up to one year, investing in commercial paper, assetbacked securities and corporate bonds, among other securities. The maximum maturity for an individual security could be as much as three years.

As surplus cash, with no identified short-term use, strategic cash can be invested over an even longer horizon of one to three years. The portfolio duration for short duration bond funds is 1.5 to 2.5 years; these funds can thus offer still-higher yields and returns than reserve funds, while controlling for risk and maintaining a focus on preservation of principal. Volatility is more noticeable, but while an investor may see deterioration in NAV on a daily or even monthly basis, this would likely not be the case over longer time periods.

EXHIBIT 2: INVESTMENT STRATEGY PER CASH SEGMENT

For illustrative purposes only

Conclusion

As we have discussed, a detailed cash forecast sets the foundation for effective cash segmentation, which has become an increasingly important tool for short-term fixed income investors. Segmenting a liquidity portfolio into operating cash, reserve cash and strategic cash allows for an optimal outcome: additional return/income within acceptable levels of volatility.

Build stronger liquidity strategies with J.P. Morgan Asset Management

Rigorous credit and risk management, combined with access to J.P. Morgan’s global resources and expertise, help us to deliver the most effective short-term fixed income solutions for our clients.

Global coordination, lasting partnerships

- Harness the power of our research-driven, globally coordinated investment process, led by our dedicated team of liquidity professionals.

- Make investment decisions based on actionable insights from our senior investors, and build portfolios based on the output of proprietary benchmarking tools.

- Select from a breadth of outcome-oriented solutions designed to help you build the most effective cash strategy.

- Tap into award-winning innovation and success of one of the world’s top liquidity fund managers, with over 30 years of demonstrated results across market cycles.