Everywhere I go, folks ask me questions. I like this. Commonly the inquisitor is an investor or a colleague, but in the era of coronavirus, I’m getting the same questions from family and friends, all of whom seem to have noticed that I’ve been on hiatus from the blog in recent months. Basically, I’ve been in the trenches with the portfolios battling the markets and the (dis)information flow, and frankly some of what I had to say in February and March was so grim that it wasn’t fit to print.

That said, I was fortunate to spend Mother’s Day weekend with my parents, the first I have seen them in months, and once again I was peppered with the same queries, and I changed the subject. Now I am circling back and trying to respond. A common theme arises: in my mind there are simple answers, and also complicated ones. Perhaps the practitioners will benefit from the simple, and family and friends will benefit from the complicated.

Question: Why are stocks so high? Three months ago if you told me unemployment would jump to multi-generational highs and stocks would only be down 10-15%, I’d say you’re nuts.

Simple Answer: I’m a bond guy, not a stock guy so anything I say on this topic can be taken with a large pinch of salt. As a macro investor though, the S&P500 remains the most visible and reliable indicator of global risk tolerance so it always factors in to my macro views, and frankly what applies here to stocks also applies to risky fixed income as I try to show.

You may not have heard it from me first, but you’ve heard it from me often: quantitative easing (QE) causes asset price inflation, full-stop. The magnitude of central bank balance sheet expansion in the past 9 weeks is tough to overstate. The Federal Reserve (Fed) alone has grown its balance sheet by $2.6 trillion in just this brief period of time. By comparison, the size of this 9 week increase is almost exactly the same as the first five years of QE beginning in 2008. Much of the recent expansion has been asset purchases (“quantitative easing”), some has been financing of assets (“not QE”), and some will be risky asset purchases (“credit easing”). The mix doesn’t matter for this question, only that the money supply (monetary base) in US dollars has expanded dramatically as a direct result, and the value of assets taken out of circulation has been equivalently large. If the world can only store its savings in two places: 1) cash and 2) everything else, when the amount of cash in circulation goes up and the amount of non-cash assets in circulation simultaneously goes down, the relative value between the two (which is the price of non-cash assets) should adjust accordingly. Economists will argue over this for years to come, but it seems pretty clear to me. So, in short, the Fed is the reason stocks are so high.

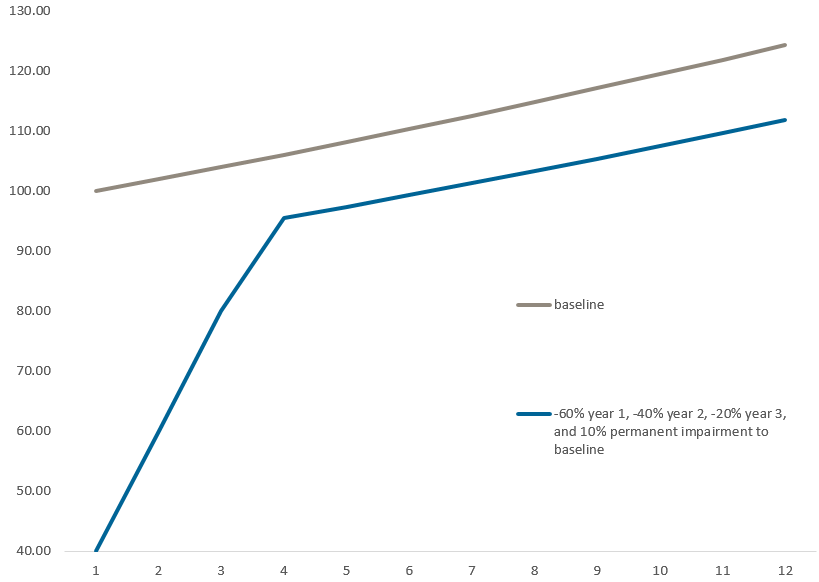

Complicated Answer: It’s actually not that hard to mathematically justify current stock prices, even in the era of coronavirus, if one sensibly assumes the value of a stock is the present value of its future earnings stream. Equities are a very long duration asset, so the mathematical value depends heavily on long-dated earnings growth, and depends less on the next few years of earnings. Watch. Imagine the following thought experiment first presented to me brilliantly by Peter Berezin at BCA research: a hypothetical company earns $100 annually as a baseline, say in 2019, with the expectation that earnings will grow 2% per year ad infinitum. Suddenly, earnings are hit by COVID-19. Earnings per share (EPS) drops by a whopping 60% to $40 in the first year of the crisis, and only claws back to $60 in the second year, $80 in the third year, and thereafter suffers a permanent 10% impairment to the original baseline. As long as the company resumes earnings growth, the mathematical hit to the stock price is only -14.3%. As I type on May 13th, the S&P is down 14% YTD. Voila. This math doesn’t require earnings to get back to $100 for the company any time soon, in this case a full 7 years. [Thanks to colleague Brandon Merrill for crunching these numbers and assistance with this discussion as a whole.]

Earnings Per Share Growth Scenarios

Source: JPMAM Calculations and adaptation of BCA Research Illustration (Peter Berezin, 4/23/2020). Assumptions: 2% risk free rate, 2% baseline EPS growth, 5% Equity Risk Premium.

Question: So are stocks too high?

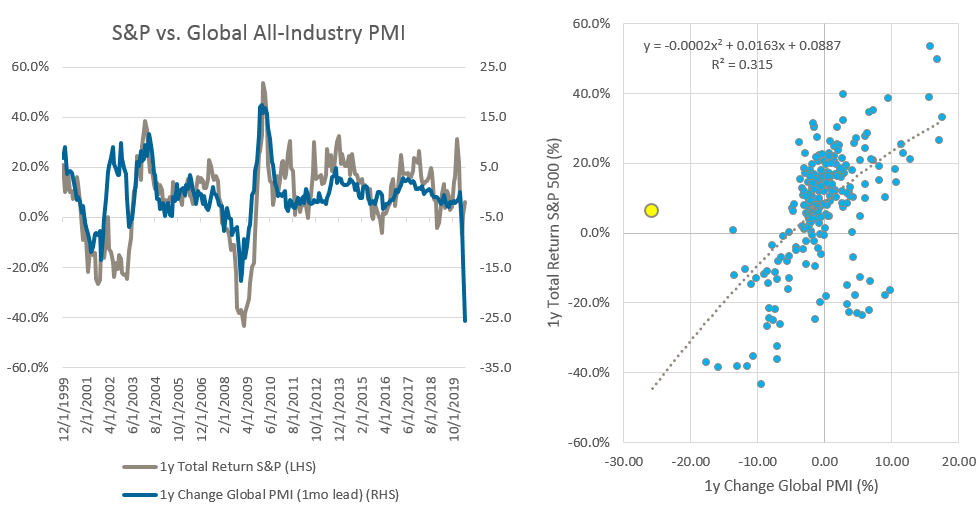

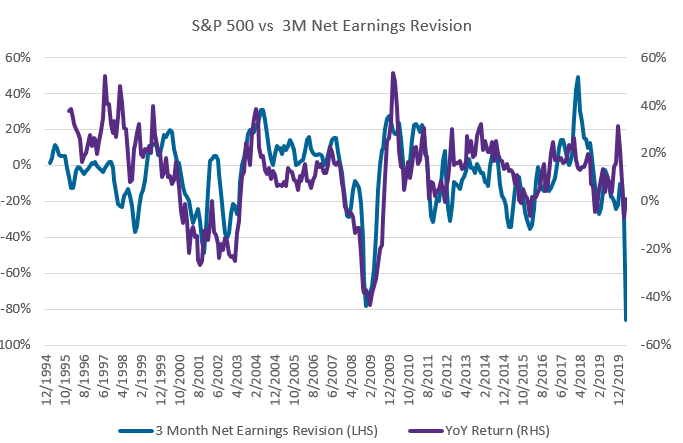

Simple Answer: Importantly, though one can use that math to justify current stock prices, I am not going to do so. I think stock prices are indeed too high. I believe the risk markets, including but not limited to equities, are much more short-term focused. What will 2021 earnings results be like? What is the high yield default rate going to be? These questions are asked, without of course querying what happens beyond that. Disappointment is likely to run high on 2021 earnings given my COVID-19 outlook below, and to put it simply: stocks tend to follow PMIs and earnings revisions, and both of those things have plummeted to nearly off-scale-lows, making current stock prices look, ahem, stretched:

Equity Earnings and Global PMIs

Source: JPMAM Calculations, data via Bloomberg as of 5/13/2020

Source: IBES and Bloomberg, as of 5/13/2020

[Thanks to Dave Rooney and our Global Rates team, and Luying Wei in our Multi-Asset Solutions team for these great charts].

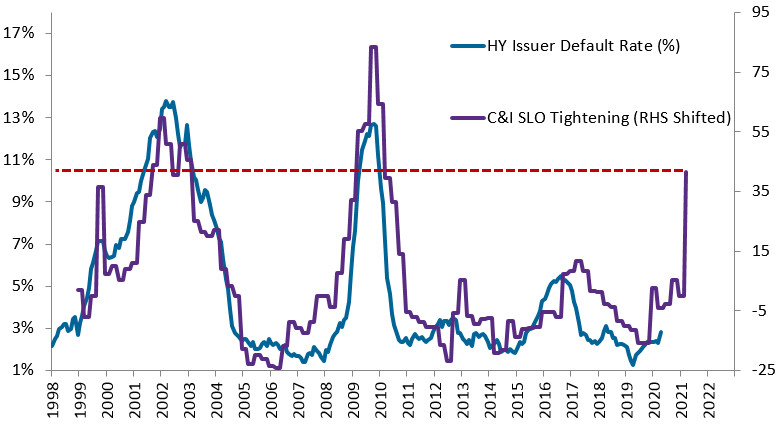

Keeping with the short-termism theme, high yield credit tends to get spooked by defaults, even if they aren’t sustained. Everyone knows the default rate is going up, but what if it goes way up?

High Yield Default Rate vs. Senior Loan Officers Tightening

Source: Credit Suisse Credit Strategy (Fer Koch, as of 5/14/2020)

For now, we have a bucket being filled with liquidity by the Fed, and the water level is rising. There’s a hole in the bottom, which is small for now, but as actual losses destroy capital (think defaults, bankruptcies) the hole gets bigger. Capital destruction is also liquidity destruction, and it’s the rate-of-change of the water level in the bucket which should influence asset prices generally (see more on that here).

Complicated Answer: Sticklers might ask what I did with the equity risk premium (ERP) and risk-free rate assumptions in the math used to “justify” stock prices in the previous question. I held them constant, but changing them can work in favor of the stock price or against it. Declining risk-free rates, which have indeed occurred over the era of coronavirus, lessens the theoretical hit to stock prices. But, widening the equity risk premium has the opposite effect, and I believe equity risk premium (and all risk premiums) should be much wider for two reasons.

First, the uncertainty around so many critically important questions on the COVID-19 progression and what our capitalistic society looks like afterward lead me to need more expected return in order to own risk ahead of any clarity on those questions. Secondly, and more importantly, I envision one of the lasting effects of the coronavirus era to be severely diminished effectiveness of risk-parity portfolios that depend on core fixed income (mostly pure interest rate duration) to diversify equity-like risk. Because central bankers were confronted with an existential threat to economic prosperity when policy rates were already quite low (this was the fear all along!) long term interest rates have now sunk to levels where there are mathematical limits to just how much price appreciation a portfolio can expect from pure interest rate products when stocks or credit or emerging markets are tanking.

We all know the high profile risk parity strategies, and yours truly has used it for much of my career, but who are the main users? Basically everyone: a standard 60-40 retirement portfolio at its core depends on bonds hedging stocks. Pure equity risk, given its volatility, needs a higher expected return (a much wider ERP) if it cannot be effectively paired with bonds to reduce portfolio risk. Sure, there are other ways to dampen equity volatility, but they tend to cost money, as opposed to pay a material positive return like Treasurys used to.

Question: What are the permanent changes that you envision post-COVID?

Simple Answer: Like the rest of this discussion it’s purely speculative (in fact there is a special COVID-speculation section in the disclaimers which follow), and the dynamism of the global developed market economies, especially the US, has proven the doubters wrong time and time again. But, here goes:

- Access to PPE, pharmaceuticals, and crisis-management tools and infrastructure are now plainly national security issues. Supply chains will need to be rerouted, and certain production will be de-globalized and turned inward, even though costs will be higher and manufacturing efficiency will be lower. Inefficiency is a headwind to profitability, and nationalism is further fuel for the (inefficient) de-globalization groundswell that was obviously already occurring pre-COVID.

- Post-Crisis savings rates for both firms and households will probably need to be higher. The need for a stronger safety net has been made painfully clear for both types of economic agents. Firms and households all of a sudden need to be able to survive a period of zero revenue, so they can’t lever as much in the future, and there is also less speculative funding for innovation. Efficiency gains are slower, and early stage funding is tighter. Again, this is a headwind to profitability and risk-taking. To take it a step further, in a closed economy, the government budget deficit must be funded by the private sector savings rate – they are mirror images of each other. In practice some of this deficit can be financed through a capital account surplus (and accompanying current account deficit) but all else equal, an increasing budget deficit would also result in a higher private sector savings rate. A reminder that what’s good for the individual agent is not good for the economy as a whole. The post-crisis deleveraging and retrenchment is well-described by economist Richard Koo in his work on Japan’s persistent sluggishness: The Holy Grail of Macroeconomics.

- Widespread adoption of Modern Monetary Theory-like policies to cushion the economic impact of the Coronavirus lockdowns may ultimately transfer the responsibility for inflation-fighting from the central banks to the legislatures. MMT allows enormous (limitless?) deficit spending until inflation occurs, at which point the deficit must be promptly closed. Politicians cannot credibly be expected to shut off the spigots when doing so would trigger a recession and their likely removal from office. While deflation is the main near-term risk with lack of demand and potential overcapacity in services post-COVID, inflation is the main long-term risk. I see no other plausible end game as long as governments continue to run central-bank-financed deficits. I wrote recently about MMT here.

Complicated Answer: So grim it’s not fit to print.

Question: Is it too soon to open the economy / what happens next with COVID?

Simple Answer: In our weekly macro meeting earlier last week, I said I felt that there was “scientific consensus” that we are opening the economy too soon, given the status of our COVID statistics. That characterization wasn’t quite right. Having studied this from all angles, even the ones which are clearly politically biased, there appears to be scientific consensus that the COVID statistics will worsen if the US reopens now (second wave, wavelets, or a natural disease progression endemic to this virus and agnostic to suppression), but for some scientists, the economic costs of lockdown and negative public health effects of foregone treatments for non-COVID conditions are too much to keep the country in lockdown. There is also my personal belief that the US is culturally incapable of adhering to a lockdown which is of sufficient rigor to truly reduce the case count to levels where contract tracing can be done. Successful reopenings in Asia (e.g. China and South Korea) were done after the daily case count was in the hundreds or less. Clearly in the US, there are still 20,000+ people per day testing positive despite the best-efforts at lockdown. The disease is just that contagious.

Complicated Answer: As a thought exercise, I tried to adopt the two most optimistic scientific stances with respect to the future COVID evolution in the US. They are: COVID has a low flu-like mortality rate (“because we’re not using the right denominator”), and the idea that the virus has some biological properties which cause its infection and mortality rates to peak naturally regardless (or in spite of!) tight lockdowns.

Each of the optimistic scenarios depend crucially on many people having been already exposed to the coronavirus with either mild symptoms or no symptoms at all. In the flu-like mortality view, the argument says that the true number of COVID cases is 20x-50x the number of confirmed cases we have counted. This idea stems from serology testing through antibody surveys (“sero-prevalence surveys”) in places like NYC (21% had antibodies), NY State (14%), Santa Clara, CA (2-4%), Gangelt, Germany (14%), which suggest that far more people have been infected than confirmed as such. There are known issues with sero-prevalence surveys, such as frequent false positives in the tests and selection bias in those tested, but in order to make my point I will ignore all that, and take the most optimistic interpretation possible: the true number of infected people is 50x the number confirmed so far. Hold that thought.

The second optimistic scenario embraces an idea that the broader scientific community is misreading the statistics and mis-modeling the actual epidemiology of COVID. The main proponent is Professor Michael Levitt (Nobel Prize in chemistry, not medicine). You can hear the details here, but the upshot is that if you analyze each individual outbreak (Wuhan, China ex-Wuhan, NYC, etc.), the cumulative number of fatalities tends to peak around 1 complete month of excess death (above the normal rate for the population group in question), and then COVID deaths wane rapidly, regardless of the intensity of mitigation techniques. Tight or loose lockdown, you get pretty much 1 extra month of excess death. As an aside, it is not immediately obvious what the biological explanation could be for this statistical phenomenon. Epidemiological models discussed in the press only seem to show decelerating case count by interventions, such as distancing and lockdowns. My suspicion is that allowing the models to incorporate a high R0 (3-4), very high asymptomatic cases (say 50+% of the total), only partial immunity after infection, and with certain low-mobility cohorts as extremely vulnerable to severe cases, that you could model an evolution which only appears to be responding to mitigation when in fact it is the natural course of disease propagation.

Here is the issue: In each of these optimistic scenarios, we are still only about one third of the way through the total number of people in the US who could be killed by COVID:

- Scenario 1: “true” case count in the US is 50mm ( = 280mm unexposed), and “true” mortality rate is only 0.1% = 280,000 deaths.

- Scenario 2: COVID results in 1 month of excess death cumulatively. 7700 people die daily on average in the US. 7700 x 30 = 231,000 excess deaths.

I think that given the cultural and political limitations on lockdown enforcement here in the US, if either of these optimistic scenarios comes to fruition, that it could be considered a public health success. Again, the epidemiologists do not agree with these forecasts (theirs are worse), but I’m looking for the most positive potential outcome. Annoyingly I do not think even the optimistic outcomes will be welcomed by markets because the post-lockdown trajectory of the COVID stats would be worse, not better. Risk markets bottomed very close to the peak in daily case counts, as Chinese markets did during their outbreak. Post lockdown that daily record may be under threat.

Lastly, I want to point out with two quick charts the extent of the politicization of COVID perceptions in the US. This polarization is based on politics and presumably preferred sources of news, but in my view, it increases the probability of poor decision-making and is bad for all Americans, left right and center.

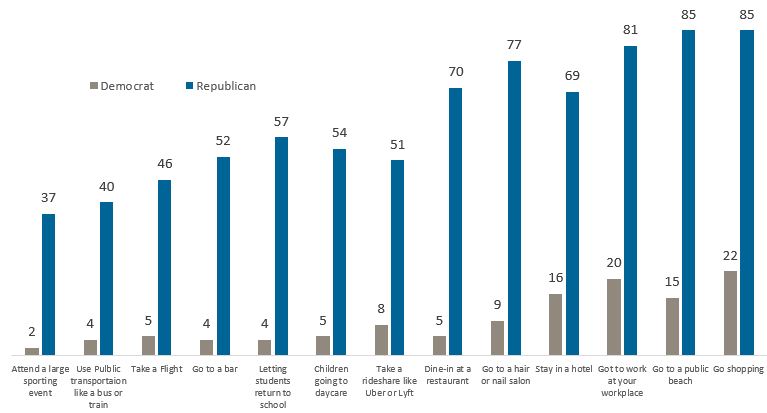

The results of a CNBC/Change Research poll conducted in battleground states the first week of May showed, among other things, that 85% of Republicans consider going shopping to be “safe” versus only 22% of Democrats (!):

% of Respondents Who Consider the Activity "Safe"

Source: CNBC/Change Research as of 5/3/2020: https://www.changeresearch.com/post/states-of-play-battleground-wave-4

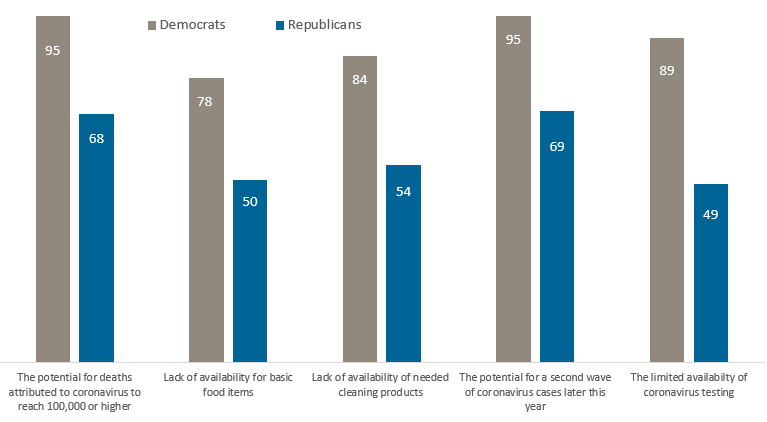

A CNN/SSRS poll from mid-May showed a similar and troubling partisan divide on key COVID-related questions:

% "Afraid" + % "Concerned"

Source: CNN, as of 5/10/2020 http://cdn.cnn.com/cnn/2020/images/05/12/rel5a.-.coronavirus.pdf

[Thanks to Ashley Sorensen for compiling these data]

Helpfully, I expect this political gap to close soon. It’s persistent for now because no one really knows what the other side of the lockdown will look like. Soon enough we will have a clearer picture. If the more concerning forecasts come to fruition, agonizing decisions will need to be made but they will be made with more information. Over the medium term, I am convinced that the mobilization of the global scientific community will vanquish the virus. Vaccine and therapeutic development is a notable bright spot of cross-border cooperation, with a healthy dose of competition among dozens of potential medicines. I’m not alone in this view however, and I think in many markets such an outcome is already reflected in asset prices. Much like health outcomes are uncertain, economic ones are as well and they are of course related. Given that uncertainty, the returns for bearing these risks need to be substantial. Those opportunities are out there, but are no longer everywhere.

COVID-19 disclosure: The extent of COVID-19’s impact will depend on many factors, including the ultimate duration and scope of the public health emergency and the restrictive countermeasures being undertaken, as well as the effectiveness of other governmental, legislative and financial and monetary policy interventions designed to mitigate the pandemic and address its negative externalities, all of which are evolving rapidly and may have unpredictable results. Even if and as the spread of the COVID-19 virus itself is substantially contained, it will be difficult to assess what the longer-term impacts of an extended period of unprecedented economic dislocation and disruption will be on future macro- and micro-economic developments, the health of certain industries and businesses, and commercial and consumer behavior. The financial performance of the Fund’s investments will depend on future developments all of which are highly uncertain and cannot be predicted at this time and the effects of which may be more adverse to the aggregate investment performance and any projected future performance of the Fund and to certain or all of the individual investments described herein than currently anticipated.