Central bank actions have created no shortage of headlines in 2022. Faced with inflation running at multi-decade highs, policymakers are caught between the proverbial rock and a hard place. Tighten policy aggressively and they risk triggering a deep recession, but do too little and they risk watching inflation expectations de-anchor as a result. The market’s angst about the prospect of tighter policy ahead has been clear for all to see.

Against this backdrop, it’s fair to say policymakers have their hands pretty full. Yet this is precisely why a headline of a different nature caught my attention recently. Despite being faced with one of the most complex macroeconomic outlooks in nearly 50 years, the European Central Bank (ECB) recently declared its intention to turn the fight against climate change into “real action”. This action includes tilting corporate bond holdings toward issuers with better climate scores, new climate-related disclosures, and enhanced risk management practices. In my opinion, it is absolutely right that environmental considerations do not take a backseat, even when accounting for today’s inflation headache.

The responsibility for facilitating an orderly transition to net zero falls primarily under a government’s remit, rather than to its central bank, yet there are nonetheless several justifications for assigning climate factors greater priority in monetary policy. It may be that a central bank has a specific mandate to support a government’s economic policies, including policies related to the energy transition. Alternatively a financial stability perspective may warrant action, with scientific research having laid out extensively the potential damage inaction might cause. Take the White House Office of Management and Budget’s recent estimates that current warming could translate into an annual revenue loss to the federal budget of about $2 trillion as an example. There is also direct feedthrough from global warming to inflation, such as the way in which droughts can force food prices higher and threaten food security.

Gauging progress

The progress made in integrating climate factors into central bank mandates varies by region. The Bank of England is one of the furthest ahead, with the UK government having changed the Bank’s remit in March 2021 to explicitly include supporting the economy’s transition to net zero. The ECB recently announced details on decarbonising its bond holdings, and its president Christine Lagarde has been a vocal advocate for why embedding environmental risks is mission critical long before this. The Federal Reserve’s (Fed’s) approach has so far been more constrained, with a focus on managing the risks to the financial system posed by climate change, for example via stress testing. In Asia, both the People’s Bank of China and the Bank of Japan have launched dedicated lending facilities to offer discounted funding for clean energy.

Policymakers have a range of options to drive change, but in my view, corporate bond purchase schemes will be their most effective tool. In a period where tighter financial conditions are the order of the day, clearly balance sheet reduction is the priority. Yet inevitably at some stage during a future downturn, the comfort blanket of asset purchases will be required again in order to ease market woes. Historically, this support has been extremely effective – US investment grade spreads fell by 100 basis points in just over a week after the Fed declared its intention to start corporate bond purchases in March 2020. In Europe, the ECB’s forceful approach to quantitative easing (QE) has pinned euro-denominated credit spreads below levels seen in the US or the UK for much of the past decade.

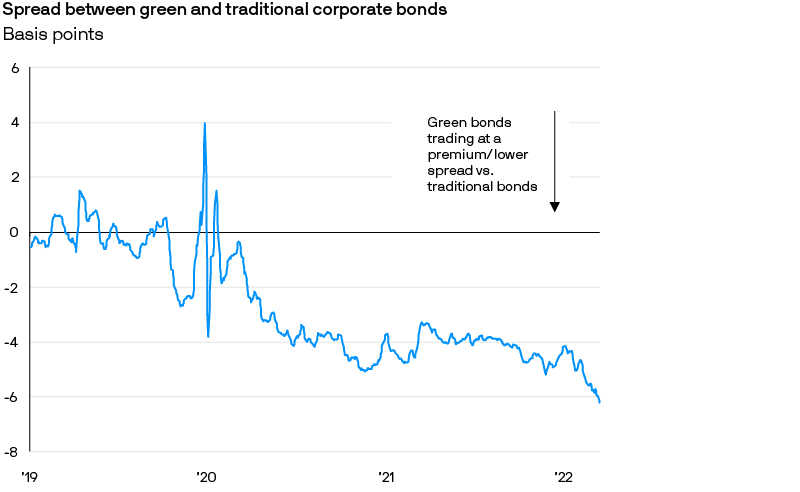

If eligibility for QE purchases is more explicitly contingent on the environmental credentials of businesses – as reinvestments now are in the eurozone – then the benefits of central bank support will be felt less evenly. There is already a clearly observed green premium, or “greenium”, in fixed income markets, where huge demand for green, social and sustainable bonds has resulted in these issues trading at lower yields than comparable “traditional” bond counterparts. As markets start to pay an increasing amount of attention to the changes afoot in central bank policy, I expect to see environmental factors driving larger differentials in spreads across the credit markets.

The ECB clearly feels that this issue is too important to ignore. Investors would be wise to take the same approach. At crunch time in previous crises, the role of central banks as a buyer of last resort has been crucial in stabilising credit markets. When the QE comfort blanket is next called upon, we may well find that it’s a little smaller than before.

Source: Barclays Research, J.P. Morgan Asset Management. Data shown is for a Barclays Research custom universe of green and non-green investment-grade credits, matched by issuer, currency, seniority and maturity. The universe consists of 164 pairs of bonds across a range of USD, EUR and GBP denominated issues. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of current and future results. Data as of 30 June 2022.

09ut220710085615