"American Gothic”: the Federal debt and how the Visigoths may try to break the system if no one fixes it

See if you can guess what the people listed below have in common:

Erskine Bowles, Democratic White House Chief of Staff

Sen. Alan Simpson, R-WY

Kevin Warsh, Federal Reserve Board, 2006-2011

Former OMB/CBO Director Peter Orzag, Obama appointee

Sen. Michael Bennett, D-CO

Stan Druckenmiller

Geoffrey Canada of the Harlem Children’s Zone

Admiral Mike Mullen, 17th Chairman of Joint Chiefs of Staff

Former President Bill Clinton

Michael Pakko, economist at The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Richard Kogan of the progressive Center of Budget and Policy Priorities

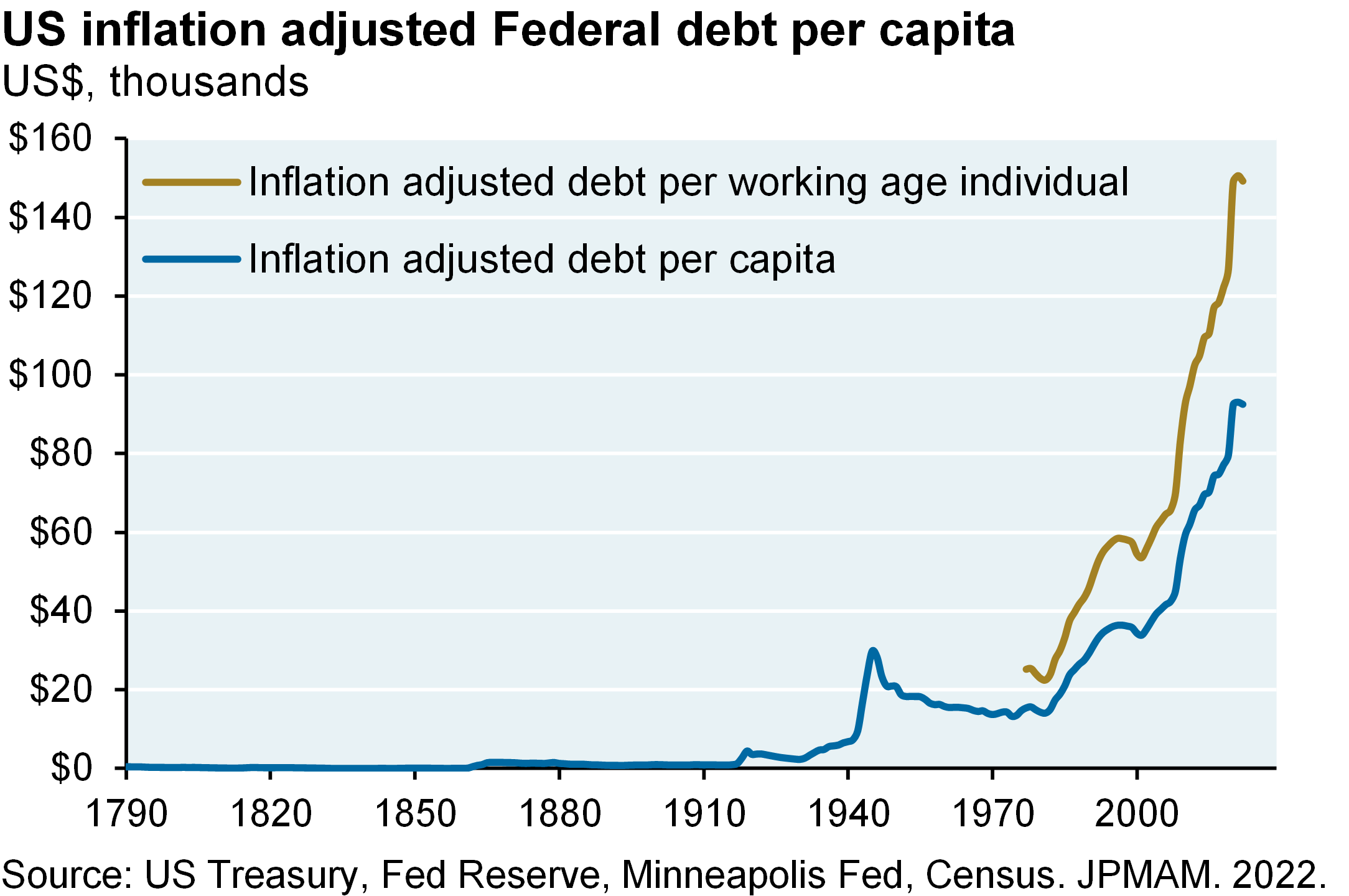

Answer: at one point or another, all these people either wrote papers1, gave speeches or worked on negotiated solutions regarding fiscal deficits, entitlements and “generational theft”, which refers to the Federal debt passed on to future generations. There has been little progress so far. Here’s a look at inflation-adjusted Federal debt per capita since 1790. After the surge in government spending required to defeat the Axis powers during WWII, each American was responsible for $30k in Federal debt in today’s dollars. Today, that figure is 3x higher, and rising. When we compute the debt burden on the working age population, it looks even worse.

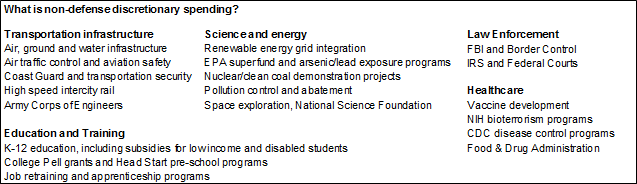

A related issue: composition of government spending as entitlements crowd out discretionary spending that contributes to productivity and future growth. Here’s a reminder of what discretionary spending is:

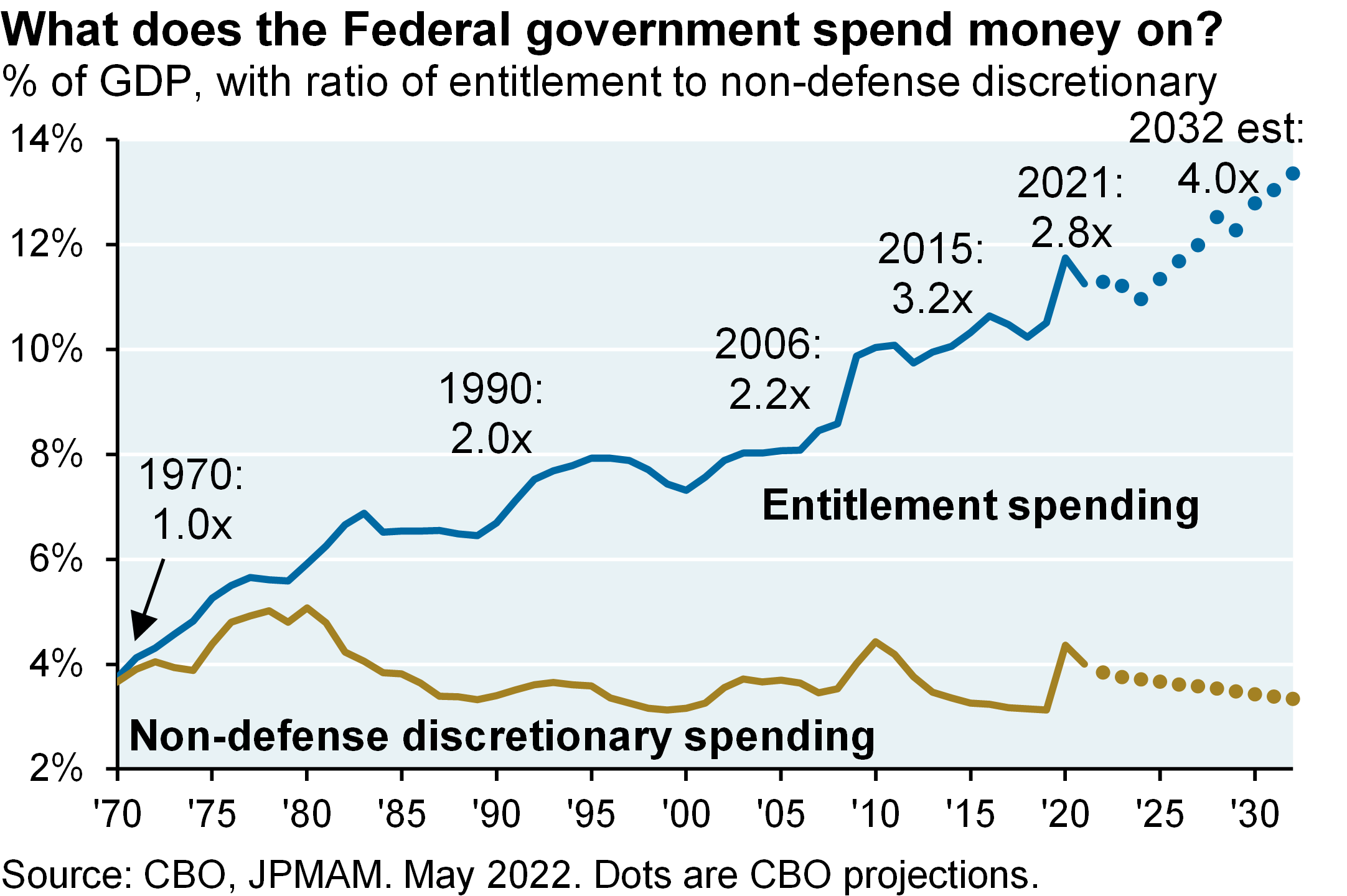

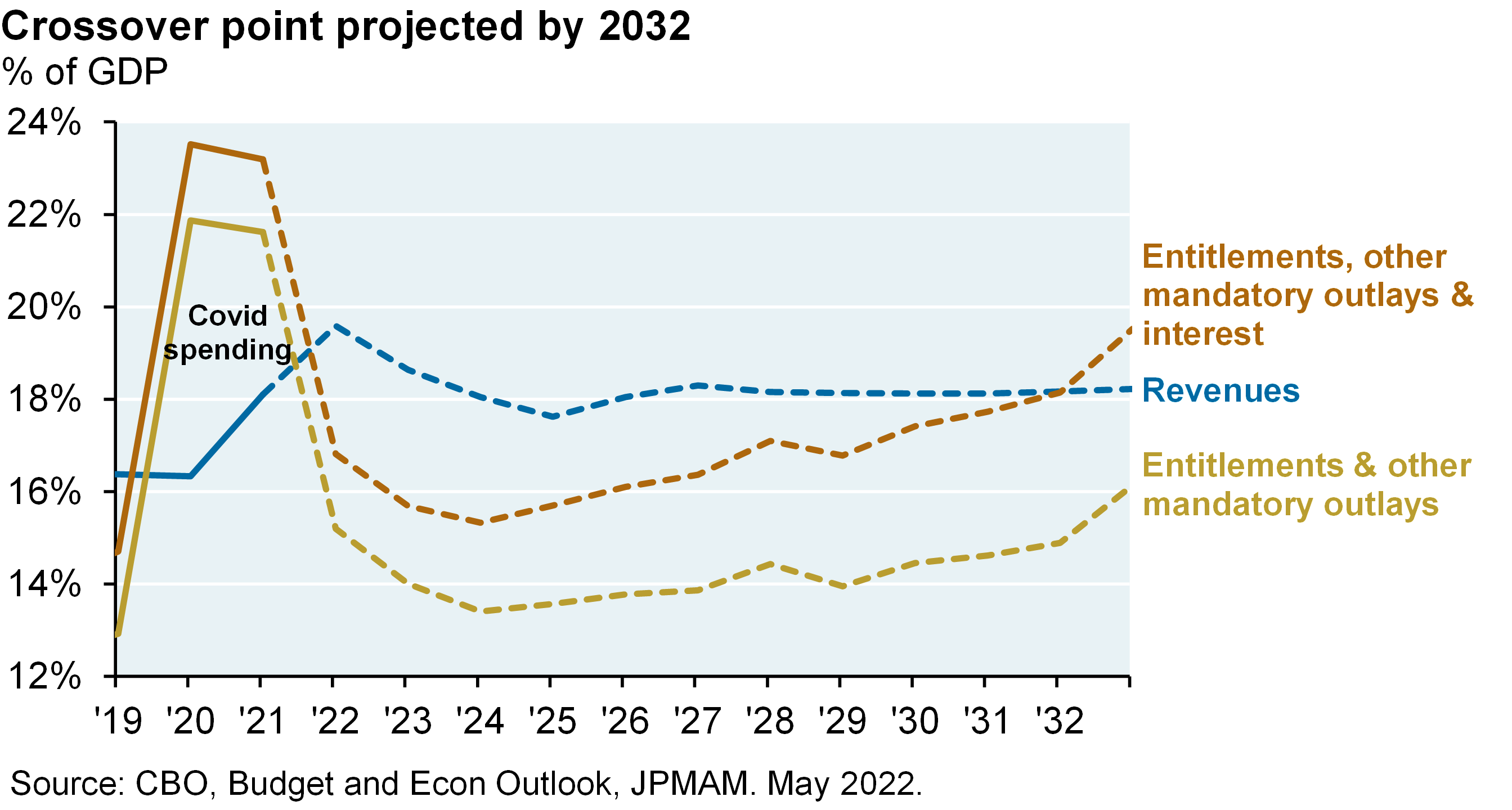

Now here’s the chart. The balance between entitlement spending and non-defense discretionary spending started out at 1.0x when Medicare and Medicaid systems were created in the late 1960’s2. That ratio is now almost 3.0x and will rise to 4.0x in a few years. By 2032, entitlement payments plus interest are expected to consume all Federal revenue collection on a permanent basis, with little left for discretionary spending (see Appendix). Some partial solutions to narrow this gap appear below3; few of them are wildly popular, and it would take a combination of them to reduce the gap back to where it was in the late 1990’s.

Partial solutions to close the gap (charts in Appendix)

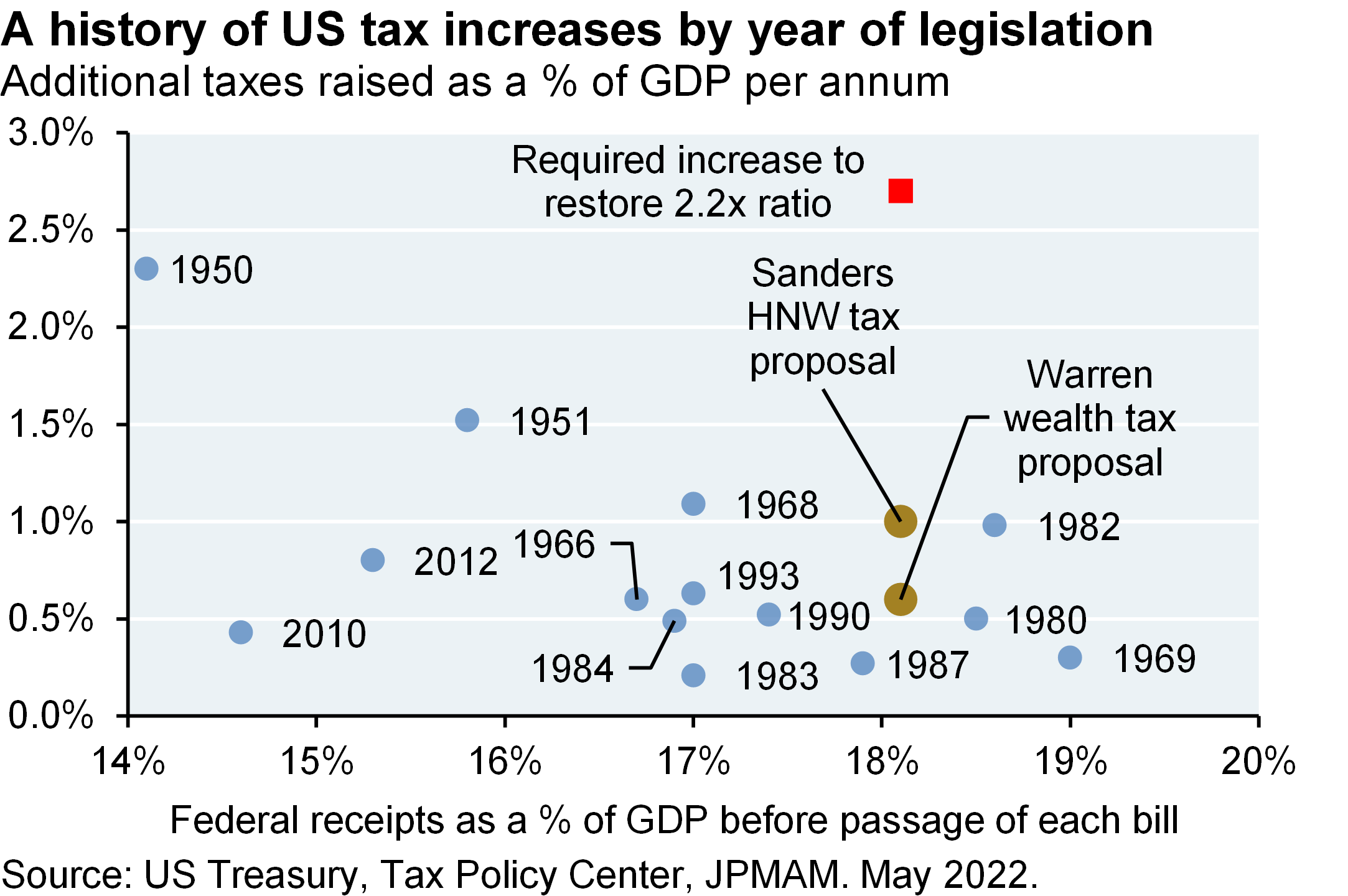

Senator Sanders plan: large increase in income/capital gains taxes on incomes > $250k, raising 1% of GDP annually, spent entirely on discretionary spending

Senator Warren wealth taxes of 1% applied in excess of $20mm, which would raise 0.5%-0.7% of GDP per year (as per TPC), spent entirely on discretionary spending

Convert Social Security from a savings program to an entitlement program, then eliminate the cap on income used to compute Social Security taxes without raising benefits; use proceeds to boost discretionary spending

Means-testing of Medicare B and D, higher Medicare co-pays and deductibles, higher eligibility retirement age, further means-testing of Social Security, increased rebates by Medicare Part D drug manufacturers

Cut defense spending, close to a 70-year low as a share of GDP at 3.5% but 3rd highest in the world per capita

So, now the Visigoths may block the debt ceiling increase unless the White House agrees to spending cuts and a balanced budget within 10 years. Here are questions I’ve been getting and my answers to them:

Would any technical default be followed in short order by political negotiations to put things back on track, such as the Budget Control Act of 2011, the Gramm Rudman Hollings Deficit Control Act of 1985 and the Balanced Budget Reaffirmation Act of 1987? I think so, but have no idea how long it could take to get there

Will the Visigoths be able to maintain a united partisan front to fight the debt ceiling increase, since only 5 GOP defections would allow it? Not sure. According to CNN, some swing-state Republicans from districts Biden won or narrowly lost, and who are seen as most likely to break ranks with GOP leadership, said they’re not willing to back a clean debt ceiling increase and are insisting on a fiscal agreement first

If the debt ceiling were not raised, could the Treasury decide to pay certain obligations (such as interest on the Federal debt) and not others, which is referred to as “debt prioritization”? Unclear. That would require the Treasury to predict upcoming cash flows accurately and withhold cash in advance. Yellen’s public statements have indicated that she considers this beyond the Treasury’s ability to execute, although a transcript from a 2013 FOMC meeting includes comments on the Treasury’s intention to pay on time4

Are Visigoth concerns about government spending genuine? Who knows and I’m not sure why it matters

Why don’t Visigoths raise the same issues when the GOP controls the White House? Politics

What might convince Visigoths to reverse course? Stock market correction, debt downgrade (e.g., 2011), opinion polls in the aftermath of a government shutdown and its various consequences

Is it “responsible” for Visigoths to do such a thing? Not according to our CEO or Janet Yellen5

Why is the debt ceiling showdown occurring a few months before prior expectations? Higher Fed Funds rates increase the amount the Fed pays on reserves, and reduces what it pays to the Treasury. Higher interest on debt may increase the 2023 deficit to $1.3 trillion, above the $1.0 trillion deficit projected last May. April’s tax receipts will provide a grace period before summer deficits bring the issue to a head sometime between June and August after cash balances and extraordinary measures run out

Would there be a lasting economic impact from a government shutdown? Probably not; in past government shutdowns, federal workers were retroactively paid for the period when their departments were closed, even when there were no binding commitments in place to do so. Businesses would probably continue to produce and accumulate inventories in expectation of resumed government purchases when the debt ceiling is eventually raised

What did fixed income investors do last time, in 2011? Some switched from T-bills to longer duration Treasuries or bank deposits. I’m not sure it’s worth the aggravation given this bottom line: a debt ceiling fight is much more likely to lead to temporary forced spending cuts than a long-lasting default on debt

Bottom line: if reasonable people cannot figure out how to fix debt and spending composition issues in a sustainable way, the Visigoths will try to do it for them, and with more economic disruption and political turmoil. If the problem goes away somehow this year, and I suspect it will, that doesn’t mean that it won’t come back again. Not sure I want to be in this role when the true day of reckoning comes.

Michael Cembalest

JP Morgan Asset Management

See Appendix for exhibits on the interest on the Federal debt, the history of US tax increases, defense spending, actual vs estimated costs of US entitlement programs and the entitlement crossover point; and a Glossary of terms you are likely to hear in the months ahead regarding Congressional proposals

Appendix

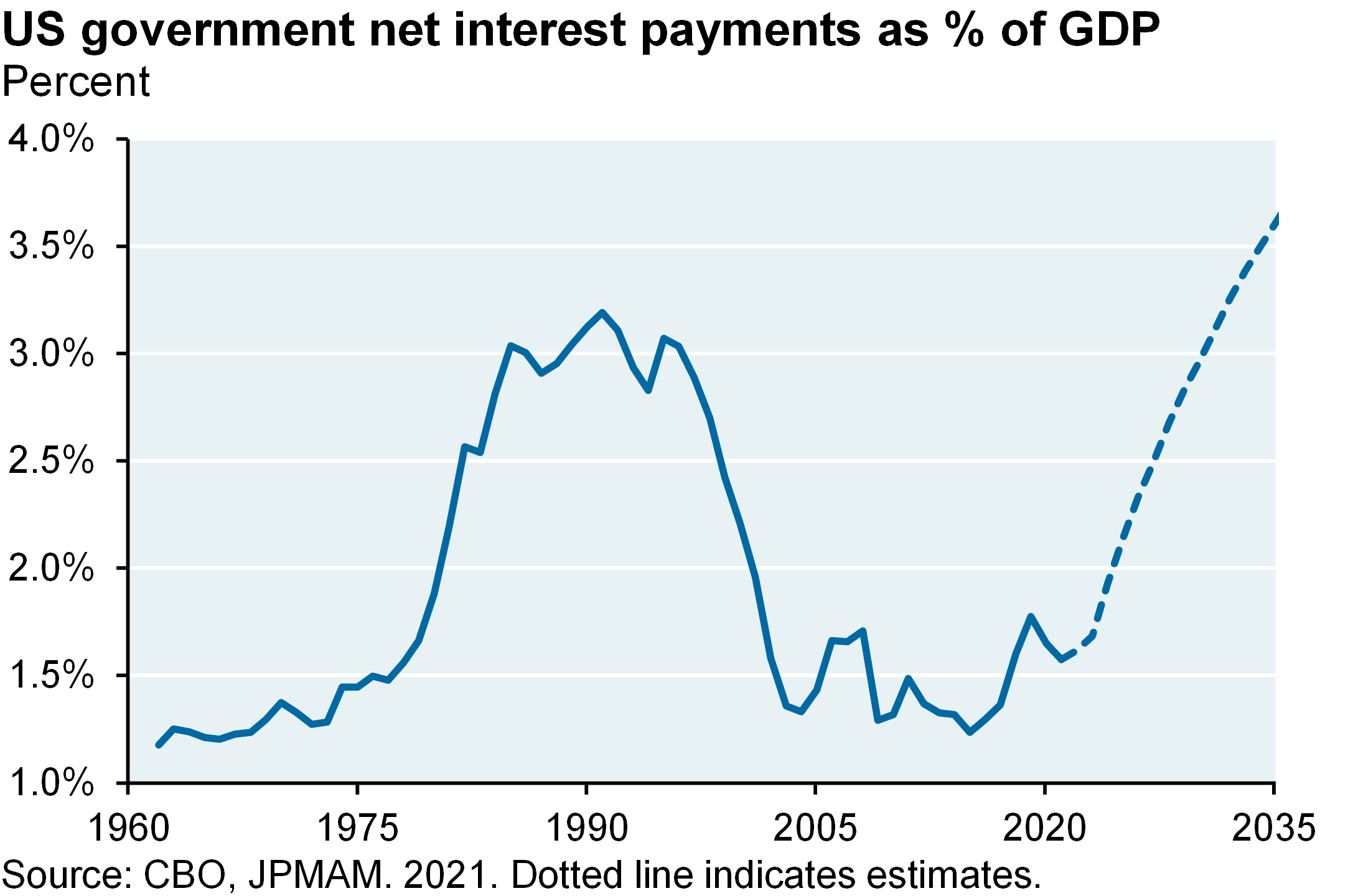

Interest on the Federal debt since 1960 with CBO projections to 2035

A history of US tax increases since 1950 (as % of GDP and vs Federal receipts as a % of GDP). While there have been tax increases of 2% of GDP or more, they occurred when overall tax receipts were much lower. The red square shows the required increases in taxes, which if spent entirely on increasing discretionary spending, would reduce the ratio of entitlements to non-defense discretionary spending back to 2.2x. The Sanders high net worth income and capital gains tax plan and the Warren wealth tax plan appear as well

US defense spending since 1940 as % of GDP, and per capita in 2021 vs other countries

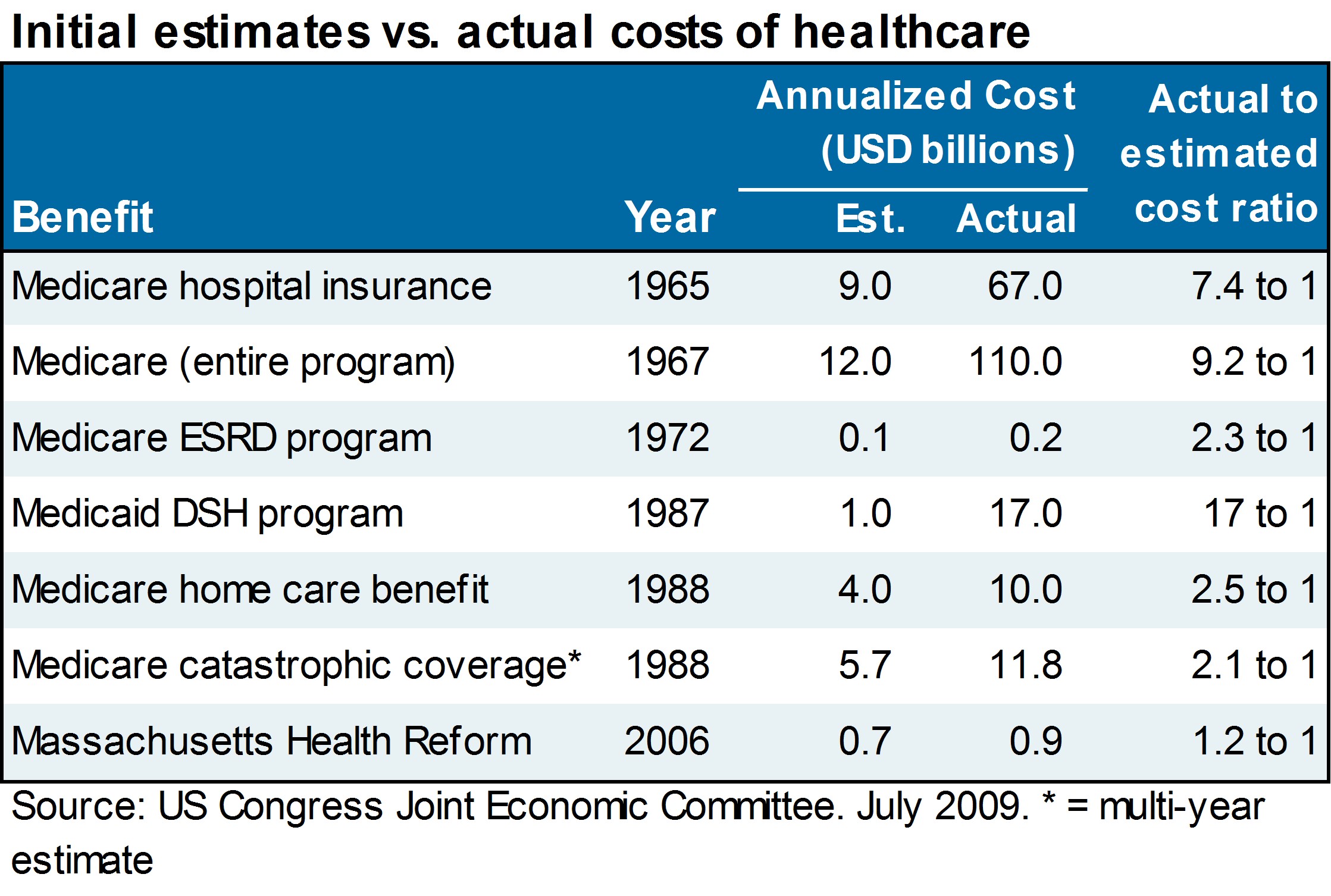

Actual vs estimated cost of US entitlement programs

Crossover point: when entitlements + interest are projected to exceed gov’t tax revenues

Debt ceiling glossary of terms

Debt Prioritization. Several Republican House members may pursue legislation to force “debt prioritization,” under which Treasury only pay some obligations and not others, as spelled out in a specific bill. The Senate is unlikely to pass this, and it might create discord within the GOP based on whose oxes are gored. Secretary Yellen has stated that Treasury does not have the ability to carry out debt prioritization (a similar conclusion was reached in 2011), and also believes that it might still be viewed by the rest of the world as a default.

Spending Cuts with a Debt Limit Vote: Speaker McCarthy and the House Republican caucus have agreed to tie any debt limit votes to new budget agreements and fiscal reforms. The demands appear to include limiting discretionary spending to FY22 levels, and adoption of a budget that balances within ten years. These are still general demands and not detailed proposals.

Bipartisan Commission: Senator Manchin (D-WV) has called for a commission to negotiate spending cuts to pair with a debt ceiling vote. At this time, Democratic Leadership has shown no interest in agreeing to this. In 2011, in exchange for GOP votes on the debt ceiling, a Congressional commission was formed to recommend deficit reduction roughly equal to the size of the increase in the debt limit.

The Trillion Dollar Coin. Could Treasury solve the impasse without Congress by pursuing options like such issuance of a $1 trillion coin to deposit at the Fed, using the funds to all bills due? Secretary Yellen dismissed this approach as a “gimmick.”

Special Procedures - House of Representatives Discharge Petition. If Democrats can find 5 or more GOP members to agree to a clean debt ceiling increase, they can try to force House Speaker McCarthy to bring the debt ceiling bill to the floor by pursuing a “discharge petition”. This would effectively force a vote on any legislative proposal in the House, and generally requires weeks of procedural steps to accomplish.

The Sack of Rome in 410 AD

Alaric I was the first king of the Visigoths, after serving in the Roman Army in support of Roman Emperor Theodosius. When Alaric marched on Rome in 410 AD, it was the first time in 800 years that the Eternal City had been attacked. The Visigoths looted and burned the city for 3 days, with the siege lifted only after thousands of pounds of gold, silver, silken tunics, scarlet-dyed hides and pepper were paid to Alaric as tribute, along with throngs of captives.

“My voice sticks in my throat; and, as I dictate, sobs choke my utterance. The City which had taken the whole world was itself taken”; Saint Jerome in a letter to Principia

1 One example: “Deficits, Debt and Looming Disaster: Reform of Entitlement Programs May Be the Only Hope”, Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis, January 1, 2009

2 20th century entitlement politics. When Medicare was introduced in the 1960s, it was described as “brazen socialism” in the Senate; one album released in 1961 was entitled “Ronald Reagan Speaks Out Against Socialized Medicine”. Two decades earlier, when Truman proposed a national healthcare program, the plan was called a Communist plot by a House sub-committee. And when FDR introduced Social Security in the 1930s, he was branded as a Communist sympathizer by Alf Landon (Roosevelt’s GOP opponent in the 1936 Presidential election), Republican Senators from Ohio, Pennsylvania and Minnesota, and publisher William Randolph Hearst.

3 Could a single-payer healthcare system bring down entitlement spending, leaving more room for discretionary spending? Unclear. Such a system would presumably require that premiums now paid to private sector insurers become taxes to fund healthcare coverage for all citizens. A single-payer system would give the government more leverage to reduce Medicaid and Medicare costs. However, unless availability and access were curtailed, a single payer system does not guarantee a cheaper healthcare system. As shown in the Appendix, the cost of entitlement programs has a history of vastly exceeding initial projections.

4Three procedures to handle government payments during a debt ceiling impasse: “The first one is that principal and interest payments on Treasury securities would continue to be made on time. The second principle is that the Treasury would decide each day whether to make or delay other government payments. The third principle is that any payments made would settle as usual. In terms of principal and interest payments, principal payments on maturing Treasury securities would be funded by Treasury auctions that roll over the maturing securities into new issues, so the new issues would fund the redemption of the maturing securities. Interest would be paid based on available cash in the Treasury general account. To make a coupon payment, however, the Treasury may need to delay or hold back making other government payments, even if it had sufficient balances on a given day, in order to accumulate sufficient funds to pay a future large coupon payment.” FOMC Conference Call Transcript, October 16, 2013

5 CNBC quoted Jamie as follows: “We should never question the creditworthiness of the US government. That is sacrosanct. It should never happen...Even questioning it is the wrong thing to do. That is just a part of the financial structure of the world. This is not something you should be playing games with at all”. Treasury Secretary Yellen said that a US debt default would "cause irreparable harm to the US economy, the livelihoods of all Americans, and global financial stability.”

This report uses rigorous security protocols for selected data sourced from Chase credit and debit card transactions to ensure all information is kept confidential and secure. All selected data is highly aggregated and all unique identifiable information, including names, account numbers, addresses, dates of birth, and Social Security Numbers, is removed from the data before the report’s author receives it. The data in this report is not representative of Chase’s overall credit and debit cardholder population.

The views, opinions and estimates expressed herein constitute Michael Cembalest’s judgment based on current market conditions and are subject to change without notice. Information herein may differ from those expressed by other areas of J.P. Morgan. This information in no way constitutes J.P. Morgan Research and should not be treated as such.

The views contained herein are not to be taken as advice or a recommendation to buy or sell any investment in any jurisdiction, nor is it a commitment from J.P. Morgan or any of its subsidiaries to participate in any of the transactions mentioned herein. Any forecasts, figures, opinions or investment techniques and strategies set out are for information purposes only, based on certain assumptions and current market conditions and are subject to change without prior notice. All information presented herein is considered to be accurate at the time of production. This material does not contain sufficient information to support an investment decision and it should not be relied upon by you in evaluating the merits of investing in any securities or products. In addition, users should make an independent assessment of the legal, regulatory, tax, credit and accounting implications and determine, together with their own professional advisers, if any investment mentioned herein is believed to be suitable to their personal goals. Investors should ensure that they obtain all available relevant information before making any investment. It should be noted that investment involves risks, the value of investments and the income from them may fluctuate in accordance with market conditions and taxation agreements and investors may not get back the full amount invested. Both past performance and yields are not reliable indicators of current and future results.

Non-affiliated entities mentioned are for informational purposes only and should not be construed as an endorsement or sponsorship of J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. or its affiliates.

For J.P. Morgan Asset Management Clients:

J.P. Morgan Asset Management is the brand for the asset management business of JPMorgan Chase & Co. and its affiliates worldwide.

To the extent permitted by applicable law, we may record telephone calls and monitor electronic communications to comply with our legal and regulatory obligations and internal policies. Personal data will be collected, stored and processed by J.P. Morgan Asset Management in accordance with our privacy policies at https://am.jpmorgan.com/global/privacy.

ACCESSIBILITY

For U.S. only: If you are a person with a disability and need additional support in viewing the material, please call us at 1-800-343-1113 for assistance.

This communication is issued by the following entities:

In the United States, by J.P. Morgan Investment Management Inc. or J.P. Morgan Alternative Asset Management, Inc., both regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission; in Latin America, for intended recipients’ use only, by local J.P. Morgan entities, as the case may be.; in Canada, for institutional clients’ use only, by JPMorgan Asset Management (Canada) Inc., which is a registered Portfolio Manager and Exempt Market Dealer in all Canadian provinces and territories except the Yukon and is also registered as an Investment Fund Manager in British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador. In the United Kingdom, by JPMorgan Asset Management (UK) Limited, which is authorized and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority; in other European jurisdictions, by JPMorgan Asset Management (Europe) S.à r.l. In Asia Pacific (“APAC”), by the following issuing entities and in the respective jurisdictions in which they are primarily regulated: JPMorgan Asset Management (Asia Pacific) Limited, or JPMorgan Funds (Asia) Limited, or JPMorgan Asset Management Real Assets (Asia) Limited, each of which is regulated by the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong; JPMorgan Asset Management (Singapore) Limited (Co. Reg. No. 197601586K), which this advertisement or publication has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore; JPMorgan Asset Management (Taiwan) Limited; JPMorgan Asset Management (Japan) Limited, which is a member of the Investment Trusts Association, Japan, the Japan Investment Advisers Association, Type II Financial Instruments Firms Association and the Japan Securities Dealers Association and is regulated by the Financial Services Agency (registration number “Kanto Local Finance Bureau (Financial Instruments Firm) No. 330”); in Australia, to wholesale clients only as defined in section 761A and 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Commonwealth), by JPMorgan Asset Management (Australia) Limited (ABN 55143832080) (AFSL 376919). For all other markets in APAC, to intended recipients only.

For J.P. Morgan Private Bank Clients:

ACCESSIBILITY

J.P. Morgan is committed to making our products and services accessible to meet the financial services needs of all our clients. Please direct any accessibility issues to the Private Bank Client Service Center at 1-866-265-1727.

LEGAL ENTITY, BRAND & REGULATORY INFORMATION

In the United States, bank deposit accounts and related services, such as checking, savings and bank lending, are offered by JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. Member FDIC.

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. and its affiliates (collectively “JPMCB”) offer investment products, which may include bank-managed investment accounts and custody, as part of its trust and fiduciary services. Other investment products and services, such as brokerage and advisory accounts, are offered through J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (“JPMS”), a member of FINRA and SIPC. Annuities are made available through Chase Insurance Agency, Inc. (CIA), a licensed insurance agency, doing business as Chase Insurance Agency Services, Inc. in Florida. JPMCB, JPMS and CIA are affiliated companies under the common control of JPM. Products not available in all states.

In Germany, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE, with its registered office at Taunustor 1 (TaunusTurm), 60310 Frankfurt am Main, Germany, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB). In Luxembourg, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE – Luxembourg Branch, with registered office at European Bank and Business Centre, 6 route de Treves, L-2633, Senningerberg, Luxembourg, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Luxembourg Branch is also supervised by the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF); registered under R.C.S Luxembourg B255938. In the United Kingdom, this material is issued by J.P. Morgan SE – London Branch, registered office at 25 Bank Street, Canary Wharf, London E14 5JP, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – London Branch is also supervised by the Financial Conduct Authority and Prudential Regulation Authority. In Spain, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE, Sucursal en España, with registered office at Paseo de la Castellana, 31, 28046 Madrid, Spain, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE, Sucursal en España is also supervised by the Spanish Securities Market Commission (CNMV); registered with Bank of Spain as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 1567. In Italy, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Milan Branch, with its registered office at Via Cordusio, n.3, Milan 20123, Italy, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Milan Branch is also supervised by Bank of Italy and the Commissione Nazionale per le Società e la Borsa (CONSOB); registered with Bank of Italy as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 8076; Milan Chamber of Commerce Registered Number: REA MI 2536325. In the Netherlands, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Amsterdam Branch, with registered office at World Trade Centre, Tower B, Strawinskylaan 1135, 1077 XX, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Amsterdam Branch is also supervised by De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) and the Autoriteit Financiële Markten (AFM) in the Netherlands. Registered with the Kamer van Koophandel as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under registration number 72610220. In Denmark, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Copenhagen Branch, filial af J.P. Morgan SE, Tyskland, with registered office at Kalvebod Brygge 39-41, 1560 København V, Denmark, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Copenhagen Branch, filial af J.P. Morgan SE, Tyskland is also supervised by Finanstilsynet (Danish FSA) and is registered with Finanstilsynet as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE under code 29010. In Sweden, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan SE – Stockholm Bankfilial, with registered office at Hamngatan 15, Stockholm, 11147, Sweden, authorized by the Bundesanstalt für Finanzdienstleistungsaufsicht (BaFin) and jointly supervised by the BaFin, the German Central Bank (Deutsche Bundesbank) and the European Central Bank (ECB); J.P. Morgan SE – Stockholm Bankfilial is also supervised by Finansinspektionen (Swedish FSA); registered with Finansinspektionen as a branch of J.P. Morgan SE. In France, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Paris branch, which is regulated by the French banking authorities Autorité de Contrôle Prudentiel et de Résolution and Autorité des Marchés Financiers. In Switzerland, this material is distributed by J.P. Morgan (Suisse) SA, with registered address at rue de la Confédération, 8, 1211, Geneva, Switzerland, which is authorised and supervised by the Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA), as a bank and a securities dealer in Switzerland. Please consult the following link to obtain information regarding J.P. Morgan’s EMEA data protection policy: https://www.jpmorgan.com/privacy.

In Hong Kong, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Hong Kong branch. JPMCB, Hong Kong branch is regulated by the Hong Kong Monetary Authority and the Securities and Futures Commission of Hong Kong. In Hong Kong, we will cease to use your personal data for our marketing purposes without charge if you so request. In Singapore, this material is distributed by JPMCB, Singapore branch. JPMCB, Singapore branch is regulated by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. Dealing and advisory services and discretionary investment management services are provided to you by JPMCB, Hong Kong/Singapore branch (as notified to you). Banking and custody services are provided to you by JPMCB Singapore Branch. The contents of this document have not been reviewed by any regulatory authority in Hong Kong, Singapore or any other jurisdictions. You are advised to exercise caution in relation to this document. If you are in any doubt about any of the contents of this document, you should obtain independent professional advice. For materials which constitute product advertisement under the Securities and Futures Act and the Financial Advisers Act, this advertisement has not been reviewed by the Monetary Authority of Singapore. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. is a national banking association chartered under the laws of the United States, and as a body corporate, its shareholder’s liability is limited.

With respect to countries in Latin America, the distribution of this material may be restricted in certain jurisdictions. We may offer and/or sell to you securities or other financial instruments which may not be registered under, and are not the subject of a public offering under, the securities or other financial regulatory laws of your home country. Such securities or instruments are offered and/or sold to you on a private basis only. Any communication by us to you regarding such securities or instruments, including without limitation the delivery of a prospectus, term sheet or other offering document, is not intended by us as an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any securities or instruments in any jurisdiction in which such an offer or a solicitation is unlawful. Furthermore, such securities or instruments may be subject to certain regulatory and/or contractual restrictions on subsequent transfer by you, and you are solely responsible for ascertaining and complying with such restrictions. To the extent this content makes reference to a fund, the Fund may not be publicly offered in any Latin American country, without previous registration of such fund’s securities in compliance with the laws of the corresponding jurisdiction. Public offering of any security, including the shares of the Fund, without previous registration at Brazilian Securities and Exchange Commission— CVM is completely prohibited. Some products or services contained in the materials might not be currently provided by the Brazilian and Mexican platforms.

JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. (JPMCBNA) (ABN 43 074 112 011/AFS Licence No: 238367) is regulated by the Australian Securities and Investment Commission and the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. Material provided by JPMCBNA in Australia is to “wholesale clients” only. For the purposes of this paragraph the term “wholesale client” has the meaning given in section 761G of the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth). Please inform us if you are not a Wholesale Client now or if you cease to be a Wholesale Client at any time in the future.

JPMS is a registered foreign company (overseas) (ARBN 109293610) incorporated in Delaware, U.S.A. Under Australian financial services licensing requirements, carrying on a financial services business in Australia requires a financial service provider, such as J.P. Morgan Securities LLC (JPMS), to hold an Australian Financial Services Licence (AFSL), unless an exemption applies. JPMS is exempt from the requirement to hold an AFSL under the Corporations Act 2001 (Cth) (Act) in respect of financial services it provides to you, and is regulated by the SEC, FINRA and CFTC under U.S. laws, which differ from Australian laws. Material provided by JPMS in Australia is to “wholesale clients” only. The information provided in this material is not intended to be, and must not be, distributed or passed on, directly or indirectly, to any other class of persons in Australia. For the purposes of this paragraph the term “wholesale client” has the meaning given in section 761G of the Act. Please inform us immediately if you are not a Wholesale Client now or if you cease to be a Wholesale Client at any time in the future.

This material has not been prepared specifically for Australian investors. It:

May contain references to dollar amounts which are not Australian dollars;

May contain financial information which is not prepared in accordance with Australian law or practices;

May not address risks associated with investment in foreign currency denominated investments; and

Does not address Australian tax issues.

American Gothic

The Federal debt and how the Visigoths may try to break the system if no one fixes it.

[START RECORDING]

FEMALE VOICE: This podcast has been prepared exclusively for institutional, wholesale, professional clients and qualified investors only, as defined by local laws and regulations. Please read other important information, which can be found on the link at the end of the podcast episode.

MR. MICHAEL CEMBALEST: Good morning, everybody. This is the debt ceiling version of the Eye on the Market Outlook. So see if you can guess what the following people have in common, Erskine Bowles, who is the Democratic White House Chief of Staff, Kevin Warsh, who was on the Federal Reserve Board for a few years, Peter Orszag, an Obama appointee, ran both the OMB and the CBO, Michael Bennett, a Senator, a Democratic Senator from Colorado, Geoffrey Canada of the Harlem's Children's Zone, Mike Mullin, the 17th Chairman of the Joint Chief's of Staff, Richard Kogan of the very progressive Center of Budget and Policy Priorities, Mike O'Pake, who's an economist at the Federal Reserve, Bank of St. Louis. These aren't people you would necessarily associate with conservative points of views on fiscal policy.

That said, all of them have either written papers, given speeches, or worked on negotiated solutions on the issue of deficits, entitlements, and generational theft. They haven't had a lot of luck so far. The first chart in the Eye on the Market this week looks at the inflation adjusted federal debt since 1790. After the surge in spending in World War II, every American was responsible for about $30,000 in debt in today's dollars. That figures now almost 100,000. And when you look at the debt burden on the working age population, it looks even worse.

In addition to overall issues about the levels of debt, you've got a bigger issue, in my opinion, on the composition of spending, because what's happening is that discretionary spending, that contributes to productivity and growth, is shrinking relative to entitlement spending. And entitlements are important and critical, we all understand the purpose, why they were created in the late 1960s. But as a reminder, non-defense discretionary spending includes all sorts of things related to transportation; infrastructure, renewable energy, energy demonstration projects, inner-city rail, high-speed rail, air traffic control, education and training, job retraining, education subsidies for low-income students, vaccine development, border control, all sorts of things go in that category.

And in the late 1960s, once the entitlement system was created, the federal government spent a dollar on each. A dollar on the entitlements, and a dollar on all the other non-defense discretionary spending categories. By the 1990s, it was two to one in favor of entitlements. It's now around in favor of entitlements. And by 2032, in 10 years, it'll be four to one in favor of entitlements. And so, it's not just the level of the debt, it's the composition of government spending that's creating some issues.

Now, there's a lot of solutions one could—one could think about here. Both Senator Sanders and Senator Warren have proposed large increases in income and capital gains taxes on people earning over $250,000 or wealth taxes in excess of 20 million. You could raise taxes, spend that money entirely on non-defense discretionary spending and close that gap. You could do means testing of Medicare Part B and D. You could have higher Medicare copays and deductibles, higher eligibility retirement ages, increased rebates by Medicare Part D manufacturers. In other words, things to bring down the level of entitlement spending relative to non-defense discretionary spending.

You could also cut defense spending and use some of that money to boost non-defense discretionary spending. Right now, defense spending in the US is close to a 70 year low, believe it or not, as a share of GDP. Although, as you might suspect, on a per capita basis, we're the third highest in the world. And so, with this backdrop, the Visigoths, as I've chosen to call them in this piece called American Gothic, the Visigoths now say they're going to block the debt ceiling increase unless the White House agrees to spending cuts and a balanced budget agreement within 10 years.

So here are some questions I've been getting on this, and my answers to them. So most importantly, if there were a technical default of some kind, would it be followed shortly thereafter by some kind of negotiation to put things back on track, such as the Budget Control Act of 2011, there was the Graham-Rudman-Hollings Deficit Control Act in '85, and then a Balanced Budget Reaffirmation Act in '87. I think so. I don't know how long it would take to get there, but I certainly think the sequence of events would be, if there were technical default, you could have some kind of negotiations, things get back on track rather than any kind of restructuring of the federal debt in any emerging markets context.

Will the Visigoths be able to maintain their united partisan front to fight this debt ceiling increase? Unclear. It would only take five GOP defections to join the Democrats to go ahead and allow a debt ceiling increase. So it's unclear. According to CNN, there are some swing state Republicans from districts that were purple, that you'd consider most likely to break ranks with GOP leadership, who are—who are also saying, like the leadership in the caucus, that they don't want to back a clean debt ceiling increase unless there's some kind of fiscal agreement.

And look, nobody—it doesn't matter very much, but nobody knows whether the Visigoth concerns about government spending is genuine. And the fact that these same issues don't get raised quite as vividly when the GOB con—when the GOP controls the White House is politics. But again, that doesn't matter, because we are where we are. In 2011, you had a debt downgrade and stock market correction. And sometimes that causes politicians to change the things that they're doing.

But the bottom line from this week's piece is that reasonable people have had around 25 years to try to do something to fix both the debt levels and the spending composition issues in a sustainable way. And they haven't accomplished anything. So I'm not surprised that the Visigoths are going to try to do it for them, and with a lot more economic disruption and political turmoil. Now, I suspect the problem will go away this year in some way. But that doesn't mean that it's not going to come back again and again in the future, given the excessive levels of debt and also, some of the spending imbalances that we've—that we've mentioned here.

So there are some interesting charts that we've got here to look at for context; the net interest payments on the federal debt as a percentage of GDP, a history of US tax increases since 1950, and showing that the Sanders and Warren proposals would only get you part of the way of where you need to be if you really wanted to close that spending gap, some history on the estimated cost of healthcare entitlement systems and how the actual costs were generally much, much higher, some information on defense spending, et cetera, et cetera, and then a glossary of terms that you will need or may need over the next few months as you're trying to decipher the political jargon coming out of DC as these negotiations go ahead. So anyway, just a brief note for us on the debt ceiling issues. And look forward to talking to you again soon. Bye.

FEMALE VOICE: Michael Cembalest, Eye on the Market, offers a unique perspective on the economy, current events, markets, and investment portfolios, and is a production of J.P. Morgan Asset and Wealth Management. Michael Cembalest is the Chairman of Market and Investment Strategy for J.P. Morgan Asset Management and is one of our most renowned and provocative speakers. For more information, please subscribe to the Eye on the Market by contacting your J.P. Morgan representative.

If you'd like to hear more, please explore episodes on iTunes or on our website. This podcast is intended for informational purposes only and is a communication on behalf of J.P. Morgan Institutional Investments Incorporated. Views may not be suitable for all investors and are not intended as personal investment advice or a solicitation or recommendation. Outlooks and past performance are never guarantees of future results. This is not investment research. Please read other important information, which can be found at www.jpmorgan.com/disclaimer-eotm.

[END RECORDING]